Main Content

Lesson 1a: Cost Concepts

Unit Cost, Average Cost, Marginal and Variable Cost

Unit or Average Cost

In general, the unit cost equals the average cost. That is, you take the total cost for a batch of units of a product and divide it by the number of units produced, which gives you the average cost. So, if a company spent $1,000,000 and made 100,000 units, $1,000,000 divided by 100,000 units is $10 per unit. That is the unit or average cost. You can also compute the average cost for service units produced, such as the average cost of a cable installation at Comcast.

Marginal and Variable Cost

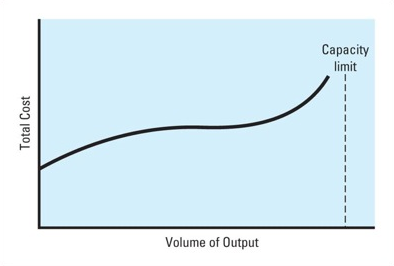

Marginal cost is not an average. It is the cost of providing one more unit of a good or service. We know that the marginal cost is not actually constant; that is, in economics we know that marginal cost is curvilinear, simply meaning a curved line. As shown in Figure 1.1, it looks like a backward "s." Also shown below (Figure 1.2 and 1.3) is how accountants convert the curvilinear marginal cost to a linear cost called variable cost.

Marginal Cost Converted to a Constant Variable Cost

As you can see in Figure 1.1, at very low levels of volume, cost is increasing, but at a decreasing rate.

Now that sounds odd, but here's an example of what is being said. You are buying automobile tires for your tire dealership from a tire manufacturer. Initially, you order 100 tires a month at $100 per tire. As you order more tires, you get a price break. So, when you increase your order above 100 tires a month, you start paying $98 per tire. Your total cost is increasing, but at a decreasing rate of $98 per tire.

At some point, the cost may level off. Assume from 6,000 to 10,000 tires per month, the price is at its lowest at $92 per tire. Above that level point, you start getting diseconomies of scale instead of economies of scale, meaning the cost per unit starts going up at an accelerating rate. So, for example, once you need over 10,000 tires per month, the manufacturer has to work overtime and offers additional tires at $102 each. Now costs are increasing at an increasing rate of $102 per tire. This explains why marginal costs are not constant.

Figure 1.2. Volume of output showing relevant range and Figure 1.3. Volume of output showing capacity limit. Source: Blocher, Stout, Juras, and Cokins, Cost Management: A Strategic Emphasis, 6th Edition, Exhibits 3.5, 3.6, and 3.7, pp. 72–73.

In managerial accounting, we simplify things by assuming we will be on a part of the marginal cost curve that is relatively straight, as shown in Figure 1.2. This results in a linear cost (a straight line) replacing the marginal cost as shown in Figure 1.3. Continuing the tire example, assuming your tire needs are expected to be between 3,500 and 3,600 tires per month, your tire cost will be constant, at say $96 per unit. Note that this is not at the lowest cost per unit, because the relevant range for your tire dealership is not high enough for that.

To distinguish the accounting linear representation from the economics marginal cost, accountants refer to this linear representation of cost as variable cost.