ACCTG340:

Lesson 1: Cost Concepts and Categories (1a thru 1e)

Written Communications in Accounting—Documenting Computations

Lesson 0 had a document titled Written Communication in Accounting. The advice there was intentionally kept short to avoid overwhelming you. Now, after submitting the Hair Dryer case, you are ready for more written communication guidance.

Three ways to document computations are displayed below with a fourth way to be covered later. All three use the Excel table format, which is preferable even when using Word or writing out computations. For clear communication, computations need to be documented on the printed page, in case a reader works with a printout. The numbers used in the examples are from the Hair Dryer Case in Lesson 0. Notice how easily you can understand the solutions presented. This is the point of good written communication—making it easy for the reader to understand what is presented.

Option 1

Option 1 is the clearest when the computations are complex or have many steps. Option 1 is always acceptable but may be overkill for simple computations.

|

Item

|

Price

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Sticker Price | $ 10.00 | |

| Sales Tax | 0.60 | |

| Gas: | ||

| Gas cost per gallon | $3.30 | |

| Divided by: miles per gallon |

30

| |

| Gas cost per mile | 0.11 | |

| Times: Extra miles driven to go to Walmart |

2

| |

| Gas cost to go to Walmart |

0.22

|

|

| Total Cost |

$ 10.82

|

|

Options 2 and 3

Some might prefer Options 2 or 3 for simple computations, simply because they do not clutter the worksheet with excessive detail, which might waste the reader's time.

Option 2

|

Item

|

Price

|

|---|---|

| Sticker Price | $ 10.00 |

| Sales Tax | 0.60 |

| Gas ($3.30 per gallon ÷ 30 miles per gallon × 2 extra miles) |

0.22

|

| Total Cost |

$ 10.82

|

Option 3

|

Item

|

Price

|

|---|---|

| Sticker Price | $10.00 |

| Sales Tax | 0.60 |

| Gas* |

0.22

|

| Total Cost |

$10.82

|

|

*($3.30 per gallon ÷ 30 miles per gallon × 2 extra miles) |

|

Option 4

We will learn a fourth way to document your computations when we use a worksheet for the activity-based costing assignment.

Introduction to Lesson 1: Cost Concepts and Categories

Lesson 1 has five parts (be sure to complete all parts):

- 1a: Cost Concepts

- 1b: Direct versus Indirect Costs

- 1c: Fixed versus Variable Costs

- 1d: Product versus Period Costs

- 1e: Income Statement: Traditional and Contribution Margin Format

I cannot overemphasize how critical it is that you learn this lesson well. You will use it throughout the remainder of the course. Those who start with a weak foundation will struggle more and more as the course progresses.

Learning Objectives

Research shows that learning objectives improve the learning process. They do this by helping the reader to focus on the major issues and to organize the new information efficiently in his or her memory. Please take the time to review and consider the learning objectives at the beginning of each lesson and make sure that you have accomplished them by the end of the lesson.

After completing this lesson, you should be able to

- use cost concepts that underlie managerial accounting;

- classify costs as direct or indirect with respect to a particular cost object;

- classify costs as fixed, variable, step, or mixed with respect to a particular cost object;

- distinguish between manufacturing, merchandising, and service firms;

- describe the difference between product costs and period costs; and

- prepare an Income Statement (Earnings Statement) for manufacturing, merchandising, and service firms.

Lesson 1 Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

Introduction to Cost Concepts

Lesson 1a covers cost terminology used throughout most cost or managerial accounting courses. These cost terms apply to all kinds of organizations: manufacturing, merchandising (whether wholesale or retail), service, not-for-profit, and governmental. In short, these terms apply to any organization that incurs costs.

This lesson will discuss the following terms:

- Cost

- Cost objects

- Cost pools

- Unit or average cost

- Marginal and variable cost

- Cost assignment

- Cost tracing

- Cost allocation

- Cost drivers

- Cost allocation bases

After you have covered this material, you will see this same list at the end of the lesson. If there is a particular term you are unclear about, you can then go back directly to the discussion of that term.

Learning Objectives

After completing this part of the lesson, you should be able to

- use cost concepts that underlie managerial accounting.

Lesson 1a: Cost Concepts—Defining Cost Terms | Video

Throughout the lessons in this course, you will often encounter video and text. Unless you are told otherwise, the video will cover the same material as the text. You have the option to use whichever format works best for you. If you choose to watch the video, you may skip the text in lesson 1a and continue to lesson 1b.

Cost Concepts: Defining Cost Terms

THOMAS BUTTROSS: There are a few lessons on basic cost concepts. This lesson is on defining cost terms and is material that is simple enough for you to master using this presentation. The learning objective is to understand and be able to use cost terms that underlie managerial and cost accounting.

Note that these cost terms apply to all kinds of organizations. Manufacturing, merchandising-- whether wholesale or retail-- service, not for profit, and governmental. In short, these terms apply to any organization that incurs costs. Note also that this cost terminology is used throughout most cost or managerial accounting courses.

The terms we're going to talk about are "cost," "cost objects," "cost pools," "unit or average cost," "marginal and variable cost," "cost assignment," "cost tracing," "cost allocation," "cost drivers," and "cost allocation basis." Later, after you've covered this material, you will see the same list at the end. That allows you, if there is a particular term, you're unclear on, to go back directly to the discussion of that term.

Cost. Now there's some very technical definitions of accounting terms. For example, when you start talking about assets, what makes something an asset in accounting has to do with its future utility. And automobile gives you future transportation. That's what makes it an asset.

It's not listed as an asset simply because you own 2,000 pounds of steel. You could get 2,000 pounds of steel much more cheaply. But it's OK in accounting for day-to-day speaking to say an asset is something of value that you own or in some cases control.

We're doing the same thing here. What is cost? A cost is what you give in return for something else. That's actually my favorite definition of a cost, what you give in return for something else.

Another definition of cost is a sacrifice made for a specific purpose. Let's review some specific examples. You give $1,000 for equipment. What is your cost of that equipment? $1,000, the amount of cash you paid.

Number two, you sign a $100,000 mortgage note for land. What is the cost of the land? The $100,000 you gave a written promise to pay.

Number three, you pay factory workers $10,000 for last week's production. Your cost is $10,000.

Number four, you pay sales staff $2,000 commission from last month's sales. Your cost is $2,000.

Number five, you pay office workers $5,000 salary for last month. Your cost is $5,000

Number six, on Saturday you spent six hours to help a friend move. What is your cost? Your cost is six hours of your life.

Now there are two things you need to note from this. First, you want to note that cost does not mean expense. Only the fourth and fifth items, the sales staff commissions, which go into commissions expense, and the office worker salary, which goes into office salaries expense, are expenses at the time of payment.

For the first item you've got equipment, a property, plant, and equipment asset. For the second item, you've got the land, a property, plant, and equipment asset. The third item you've got work in process, which is an inventory account among the current assets.

And for the last item where you helped your friend move, you've got an account receivable from your friend. However, if you do not have an account receivable from your friend, you could have an expense in that particular instance.

The second thing you should know from the above examples is that cost does not mean cash outlay. Take number two. There's no cash being paid in number two. There's a written promise to pay later, yet we still have a cost.

And take number six, where you gave up six hours of your life to help your friend move. There's a cost there, but there's no cash outlay. In the case of number six, there never will be a cash outlay.

Cost objects. A cost object is any item for which someone desires a cost. Now to say any item for which someone desires a cost may be an overstatement. For example, the janitor at IBM could say, I'd like to know what it costs to do something at the company. However, it is very unlikely that the janitor would have the power or the authority to go to accounting and demand that they compute and provide the cost.

So some people will say it is anything for which a manager desires a cost or anything for which someone with the power to get the cost desires a cost. Let's review some specific examples.

Products, such as a car. A product is a common example that anyone would have thought of off the top of their head. Some additional examples will show cost is not just a narrow thing that's applied to a product at a manufacturing company.

Product line, such as digital single-lens reflex cameras. This one's pointed out because it is common practice among the Japanese. An American company would make four different cameras and we would actually try to determine the profitability of each of those four cameras.

What a Japanese company would do is look at the profitability of the overall camera line. They will say, OK, here at Canon we have four cameras in our single-lens reflex camera line. We will sell the entry-level camera near break even. The next level up might sell at a 30% profit, the third level at a 50% profit, and top level at an 80% profit.

Canon might take the position that it is willing to have very little profit on its entry-level camera to get someone to buy a Canon. The profit margin goes up, because as people move up the line they start buying for features, not cost. As long as the overall camera line is making a healthy profit, Canon is happy.

The advantage this provides the Japanese is that when they treat the entire product line as a cost object instead of individual cameras, they have a lot less cost allocation to do.

For example, assume that all four cameras are made at the same plant. In an American computation by product, you would have to allocate the plant depreciation among the four cameras. In the Japanese company, you simply charge the plant depreciation to the camera line.

This discussion is not advocating that the Japanese practice of doing product lines in some cases as opposed to individual products is superior to the common American way of costing individual products. It is just presenting an alternative view, an alternative way to look at the world.

Number three, services such as changing the oil in a car. If you're going to open a Jiffy Lube, you need to know what it costs you to change the oil in a car.

Number four, jobs. If you're opening an accounting firm, each client is billed for the particular services he or she desires. To work for Exxon, you need to know what it would cost you to do the Exxon audit or the Exxon tax return.

Note that you might charge for particular services within the job. For example, an accountant might say, I charge $100 per hour for tax return preparation. Or I charge $100 to prepare a Schedule D.

Number five, projects such as research and development on a new drug to lower cholesterol.

Number six, organizational units. What does it cost to run the purchasing department or the human resources department? That would be especially important if an organization is considering outsourcing.

Number seven, activities or processes such as credit card authorization or order entry. What does it cost to do a credit card authorization? If it costs you $0.25 to do a credit card authorization, do you really want to do one on a $0.25 sale or a $1 sale? Or do you want to have some minimum level?

Number eight, distribution channels such as internet sales versus retail outlet sales. This particular example comes from Dell, which years ago did an activity-based costing study and decided that internet sales were more profitable than retail outlets sales and quit doing retail outlet sales. While Dell has re-entered the retail outlet market, it has not eliminated use of the internet.

Number nine, customers such as Wal-Mart. What does it cost me to service Wal-Mart? Is Wal-Mart a profitable customer? It is easy to know the sales revenue from Wal-Mart. If the organization can come up with the full cost of servicing Wal-Mart, the cost of goods sold, the shipping, the cost of calling on the customer, the costs of handling its orders and everything else, the organization can decide how profitable Wal-Mart or Sears or some other company is as a customer.

This customer profitability analysis, which requires you to know customer cost, is actually a very interesting area, because studies show that for a lot of companies 20% of customers provide 80% of the company's profit, and another 60% of customers provide another 40% of the company's profit.

If you're quick with your math, you're thinking, wait a minute, if I've got 80% and then 40%, that's 120%. You can't have more than 100%. And you're all right. The remaining 20% of customers will actually eat away 20% of the company's profit. That is, the company is losing money on them.

So doing customer profitability analysis can be a good way to increase your profitability by making sure you treat your good customers well and either make your unprofitable customers profitable or let them go elsewhere.

Cost pools. Accountants pool the cost together for various cost computations. So a cost pool is simply a related group of costs that is meaningful to a particular entity. There are many ways to pool costs. We will only look at three examples here.

Manufacturing overhead is a good example. All of the costs of running a factory, other than direct materials and direct labor, are collectively called manufacturing overhead. All of the manufacturing overhead for the entire factory could be added into one pool and allocated together using direct labor hours for the allocation.

On the other hand, some companies, because they have very different overhead used for assembly versus finishing-- let's say the assembly is very machine intensive and finishing is very labor intensive-- may actually accumulate overhead separately for assembly and finishing and allocate it separately.

In assembly they might allocate the overhead using machine hours since it is machine intensive. And finishing them they would allocate the overhead using direct labor hours, since it is very direct labor intensive.

Departments such as accounting, human resources, and shipping are a common way that companies accumulate their costs and pool them together.

Third, geographical regions such as the cost of North American operations versus Asian operations. In order for companies to know their profitability by geographic region, they have to have costs broken down that way.

Unit or average cost. In general, the unit cost equals the average cost. That is, you take the total cost for batch of units of product and divide it by number of units produced, which gives you the average cost.

So if a company spent $1 million and made 100,000 units, $1 million divided by 100,000 units is $10 per unit. That is the unit or average cost. You can also compute the average cost for service units produced such as the average cost of a cable installation at Comcast.

Marginal and variable cost. Marginal cost is not an average. It is a cost or providing one more unit of a good or service. We know that the marginal cost is not actually constant. That is, in economics we know the marginal cost is curvilinear, simply meaning a curved line.

And as the next slide shows, it actually looks like a backward S. The next slide will also show how accountants convert the curvilinear marginal cost to a linear cost called "variable cost."

We will cover the diagrams from the left to the right. In the left-most column, at very low levels of volume cost is increasing, but at a decreasing rate. Now that sounds odd, but here's an example of what is being said.

You're buying automobile tires for your car dealership from a tire manufacturer. Initially you order 100 tires a month at $100 per tire. As you order more tires, you get a price break. So when you increase your order above 100 tires a month, you start paying $98 per tire. Your total cost is increasing, but at a decreasing rate. At some point, the cost may level off. From 2,500 to 10,000 tires per month, the price is $92 per tire.

Above that level, you start getting dis-economies of scale instead of economies of scale, meaning that the cost per unit starts going up at an accelerating rate. So for example, once you need over 10,000 tires per month, the manufacturer has to work overtime and offers additional tires at $102 each. Now costs are increasing at an increasing rate again. This discussion explains why marginal cost is not constant.

In managerial accounting we simplify things by assuming we will be on the part of the marginal cost curve that is relatively straight, as shown in the middle diagram. This results in a linear cost, a straight line replacing the marginal cost as shown in the third diagram at the right. Assuming your tire needs are expected to be between 3,000 and 4,000 tires per month, your car costs will be $92 per unit, which is constant.

To distinguish the accounting simplification from economics marginal costs, accountants refer to this linear representation of cost as "variable cost."

Cost assignment. Cost assignment is a general term indicating the process of putting costs incurred into cost objects. How do we assign costs? In general there are two ways to do it. We either trace a cost we allocate the cost.

Cost tracing is the placement of a cost that belongs to only one cost object into that cost object. To the extent that you can trace cost, determining cost is easy. The costs that can be traced are called "direct costs," and they are covered in another presentation.

Cost allocation. Cost allocation is the placement of a cost that belongs to two or more cost objects into those cost objects. When a cost cannot be traced and therefore has to be allocated, it is called an "indirect cost." Indirect costs are also covered in another presentation, along with direct costs.

Here's an extremely important point about cost allocations that people do not always realize. Numbers are very precise-looking, so someone says that the product cost for making a particular part is $17.33. People tend to think of that as gospel. But a lot of cost allocations went into that $17.33. If you change the way the cost allocations are done, it might be $16.05 or $18.10, and these other amounts might be just as correct, that is, just as defensible.

So what is the point? The point is there is more than one logically defensible way to allocate the same costs to the cost objects. And if there is more than one logically defensible way to allocate the cost, then there's more than one right answer.

From the standpoint of an independent observer, the choice between multiple right answers is arbitrary. So accountants say that all cost allocations are arbitrary.

A simple example is depreciation methods. One company might allocate depreciation of its machinery based on a 10-year life with no salvage value. Another might allocate depreciation on the same equipment based on 1 million units of output. A third organization might allocate it based on a 9-year life with a 10% salvage value.

Each time you change the way you calculate depreciation or change any of the depreciation assumptions, you will get a different amount of depreciation allocated to each unit of product produced. Which cost per unit is correct? Well, they're all correct as long as your assumptions are reasonable.

Notice that your assumptions need to be reasonable. You cannot simply say, oh well, if they're all right, I'm just going to use a 10,000-your life for my equipment. Of course that's not reasonable.

All cost allocations are arbitrary. You want to remember that no matter how precise your costs look when you hand them to people, the number is not the right answer. In fact, if someone says the true cost is, he or she is misspeaking, because there is no one true cost. At best, all you can reasonably say is that some cost calculation is more accurate than others for the particular decision to be made.

Cost drivers. A cost driver is a cause of cost. If you do more of it, it drives your cost up. If you do less of it, it drives your costs down. Let's review a couple of examples here just to solidify the concept.

Set up machines, example one. First a little background. Some companies have crews that go out and set up the machines to make the next batch of product. It can be something as simple as cleaning the paint tank to switch from painting red to painting green. It can be an auto company that is stamping bumpers, changing the dye in the machine so they can start stamping doors.

What causes the cost? You've got a cost pool called set up machines, and there's $1 million in it. Where did that $1 million in cost come from? Part of it is from the number of production runs scheduled. Assuming that each production run requires a setup, then every time you schedule another production run the setup crew has to go out and change your machine and that's costly.

The length of time it takes to do a setup is another part. A four-hour setup is more costly than a one-hour setup. The scheduling of the setups is another factor. If you have your setup crew doing the setup while the factory's in full operation and they have to make production workers stand and wait, that's going to be a more costly setup than if you have the setup crew do the setup while the factory is closed or do the setup on an extra machine that is idle.

The size and pay rate of the setup crew affects the cost. If you give your setup crew a 5% raise, everything else held equal, your setups are going to be more expensive than they were before the raise.

The equipment available for setups and its condition affects the cost. If you're using old forklifts that break down, it's going to impact the time and cost of doing a setup.

Shipping is another example. Shipping cost is caused by a number of factors. The number of shipments. More shipments cost more money. The method of shipment. Shipping overnight is most of the shipping for five-day delivery. The size of the shipment. If you have 2 boxes that are each 10 pounds and 1 is a square foot while the other is 5 square feet, the bigger one is more expensive to ship.

The weight of the shipment. If you have 2 boxes that are each 2 square feet and one weighs 10 pounds while the other weighs 40 pounds, the heavier one is more expensive to ship.

The fragileness of the shipment. Assuming you're either paying extra insurance for the fragileness or you are replacing items a break in shipment, more fragile items are more expensive to ship.

The size and pay rate of the shipping department staff.

So there are a lot of things that drive costs. Now why are we covering this? If you're going to manage cost in an organization, the first thing you need to do is figure out what is driving cost. Let's take this shipping cost. I can look at this list and say, wow, we've got all the shipping costs and there are many things listed on the slide that are causing it. What should I attack first?

Well, what if you found out that your organization so behind on customer orders that it is shipping overnight 40% of the time? Then perhaps you should attack the method of shipment first and try to fix the system so that you don't need to use overnight shipping frequently.

Then you look again and ask what is now the biggest contributor to shipping costs? If you have a lot of breakage in shipment which you have to replace, you could review how you pack your shipments.

Cost allocation basis. This is an extremely important concept. I'll go as far as to say that you can't do well in cost or managerial accounting if you don't understand cost allocation basis.

Cost allocation basis is an extremely important subject that any student of managerial or cost accounting must master early in the course. Because there's no single correct way allocate a particular cost, there's no single right answer when doing allocation. Still estimates of cost are needed, making cost allocation necessary.

You should know from your high school math that the top of a fraction is called the numerator and the bottom is called the denominator. The cost allocation base is the denominator of the cost allocation fraction.

For example, $200,000 of manufacturing overhead divided by 10,000 machine hours equals $20 of manufacturing overhead per machine hour. In this case, machine hours are the allocation base.

Notice that whenever you do a fraction you're always suppressing the denominator to one and saying how much numerator you have for every one of the denominator. Let's just say that in your hometown there are 1,000 dogs and 100 cats. Well 1,000 dogs divided by 100 cats is 10 dogs per cat. If you flip it and put the 100 cats over the 1,000, it is 0.1 cats per dog.

You're always ended up with one of the denominator and saying how much of the numerator there is for that one of the denominator. If you keep that in mind, any fraction you learn is a pretty simple thing.

If you get into financing, you learn the debt-to-equity ratio, which is debt divided by equity. What does it tell you? It tells you the amount of debt for every $1 of equity. Note that you have to know how debt is defined. Is it just long-term liabilities or all liabilities? What do you mean by equity? Is it just stockholders' equity or is it creditor and stockholders' equity? But the point is that the fraction, debt-to-equity, is simply the amount of debt for every $1 of equity.

We have the unit level allocation basis. What do we mean by unit level? The allocation base changes proportionally with changes in production. If production goes up 10%, the base goes up 10%, and if production goes down 4%, the base goes down 4%. It's called unit level, because it changes along with the units.

Let's look at three unit level allocation bases. Direct labor hours, if you're going to increase production 10%, then you should need 10% more direct labor hours. Direct labor dollars. If you're using 10% more direct labor hours, you're going to pay 10% more direct labor dollars. Machine hours. If you increase production 10%, you're going to need to run the machines 10% longer.

So these are called unit level, because they vary with the number of units produced. You could also have unit level allocation bases that vary with the number of units sold. Sales commissions vary with the number of dollars sold, so commissions are unit level with respect to sales revenue.

Some costs are unit level. For example, factory machinery or electricity is unit level. If you make 10% more units, you run the machines 10% longer, and your electric bill is going to go up about 10%.

Allocating it based on a unit level allocation base such as machine hours is logical. However, a unit level allocation base is often used to allocate costs that do not vary with the number of units produced.

Factory building depreciation is not unit level. Allocating it with the unit level allocation base can lead to misleading cost calculations. For example, your building depreciation is $1 million a year and you make 200,000 units, so you say it is $5 a unit. Well, it is $5 a unit if you make 200,000 units. If you make 100,000 units, it would be $10 per unit. If you make 500,000 units, it would be $2 per unit.

When you start using the unit level allocation base to allocate something that is not unit level, people can start thinking it is unit level and make some very bad business decisions. That's something you need to watch out for.

For any cost delegation it's preferable to use a cost driver as the denominator. That is, use a factor that actually causes the particular cost in the numerator to change. When using a cost driver, focus on the one cost driver considered best suited for allocation.

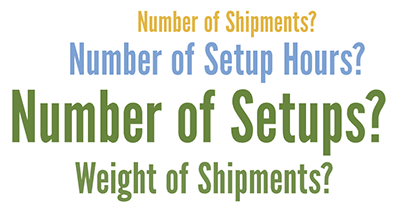

You might allocate setup machines cost using the number of setups or the number of setup hours. You might allocate shipping costs using the number of shipments or the weight of shipments if weight is the most important factor.

Something to remember is that the best cost driver for allocating the cost might not be the most important cost driver for managing the cost. You shouldn't forget that other cost drivers exist.

For example, you might allocate setup machines cost based on the number of setups. However, you might decide that decreasing the time they needed to do a setup, decreasing setup hours, is the most important cost driver for managing the cost.

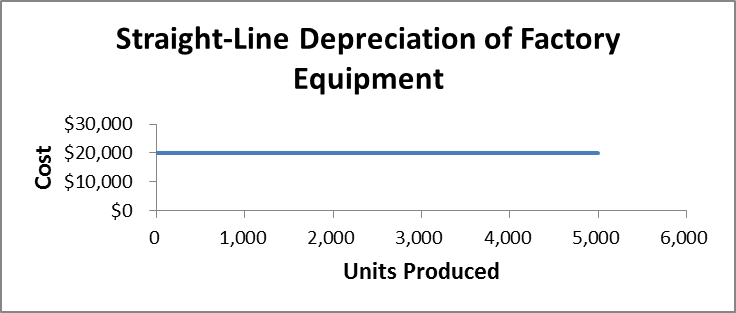

Sometimes you cannot use a cost driver to allocate a cost because there is no cost driver. An example is straight-line depreciation of a factory building, which is based on the passage of time.

You cannot logically allocate using direct labor hours or number of setups or any other denominator that drives the cost, because it is strictly a function of time. We might allocate it based on square footage used by different product, which is logical, but changing the square footage used by any product does not change the depreciation.

Where a cost driver is not available, there are other criteria for selecting an allocation base that are covered in another presentation.

You are now familiar with a variety of cost accounting terms. Think about your understanding of each one as we review the list. "Cost," "cost objects," "cost pools," "unit average costs," "marginal and variable cost," "cost assignment," "cost tracing," "cost allocation," "cost drivers," "cost allocation bases."

If you're not comfortable with any of these terms, review it again. These terms are fundamental to any study of cost or managerial accounting and any lack of understanding can cause you problems later. This is the end of defining cost terms.

Cost

There are some very technical definitions of accounting terms. For example, when you start talking about assets, what makes something an asset in accounting has to do with its future utility. An automobile gives you future transportation and that's what makes it an asset. It's not listed as an asset simply because you own two thousand pounds of steel. You could get two thousand pounds of steel much more cheaply. But it's OK in accounting for day to day speaking to say an asset is something of value which you own, or in some cases control.

We're doing the same thing here. What is "cost"? A cost is what you give in return for something else. That's actually my favorite definition of a cost—what you give in return for something else. Another definition of cost is a sacrifice made for a specific purpose.

Let's review some specific examples:

- You give $1,000 for equipment. What is your cost of that equipment? $1,000, the amount of cash you paid.

- You sign a $100,000 mortgage note for land. What is the cost of the land? The $100,000 you gave a written promise to pay.

- You pay factory workers $10,000 for last week's production—your cost is $10,000.

- You pay sales staff $2,000 commissions for last month's sales—your cost is $2,000.

- You pay office workers $5,000 salary for last month—your cost is $5,000.

- On Saturday, you spent six hours helping a friend move. What is your cost? Your cost is six hours of your life.

There are two things you need to note from this:

First you want to note that cost does not mean expense. Only the fourth and fifth items, the sales staff commissions, which go into commissions expense, and the office workers salary, which goes into office salaries expense, are expenses at the time of payment. For the first item you've got equipment: a property, plant, and equipment asset. For the second item you've got land: a property, plant, and equipment asset. For the third item, you got work-in-process which is an inventory account among the current assets. And for the last item, where you helped your friend move, you've got an account receivable from your friend. However, if you do not have an account receivable for your friend you could have an expense, in that particular instance.

The second thing you should note from the above examples is that cost does not mean cash outlay. Take Number 2; there is no cash being paid in Number 2. There is a written promise to pay later. Yet we still have a cost. And take Number 6, where you gave up six hours of your life to help your friend move. There is a cost there, but there is no cash outlay. And in the case of Number 6, there never will be a cash outlay.

Cost Objects and Cost Pools

Next, we will discuss cost objects and cost pools.Cost Objects

A cost object is any item for which someone desires a cost. Now, to say any item for which someone desires a cost may be an overstatement. For example, the janitor at IBM could say, "I'd like to know what it costs to do something at the company." However, it is very unlikely that the janitor would have the power or the authority to go to accounting and demand that they compute and provide the cost. So, some people would say it is anything for which a manager desires a cost, or someone with the power to get the cost, desires a cost.

Let's review some specific examples:

Products

Products, such as a car. A product is a common example that anyone would have thought of immediately. Some additional examples will show cost is not just a narrow concept that's applied to a product at a manufacturing company.

Product Lines

Product lines, such as digital single lens reflex cameras. This example is included because it is a common practice among the Japanese. An American company that makes four different cameras would likely try to determine the profitability of each camera. A Japanese company will look at the profitability of the overall camera line. Assume Nikon has four cameras in its single lens reflex camera line. Nikon might sell the entry level camera near breakeven, the next level up might sell at a 30% profit, the third level at a 50% profit, and top level at an 80% profit. The company might take the position that it is willing to have very little profit on its entry level camera to get someone to buy Nikon. The profit margin goes up, because as people move up the line, they start buying for features, not cost. As long as the overall camera line is making a healthy profit, Nikon is happy.

The advantage this provides the Japanese is that when they treat the entire product line as the cost object, instead of individual cameras, they have a lot less cost allocation to do. For example, assume that all four cameras are made at the same plant. In an American computation by product, you'd have to allocate the plant depreciation among the four cameras. In the Japanese company, you simply charge the plant depreciation to the camera line. This discussion is not advocating that the Japanese practice of doing product lines in some cases, as opposed to individual products, is superior to the common American way of costing individual products. It is just presenting an alternative way to look at the world.

Services

Services. If you're going to open a Jiffy Lube, you need to know what it costs you to change the oil in a car.

Jobs

Jobs. If you're opening an accounting firm, each client is billed for the particular services he or she desires. To determine whether your work for Exxon is profitable, you need to know what it cost you to do the Exxon audit or the Exxon tax return. Note that you might charge based on time or based on particular services within a job. For example, an accountant might say, "I charge $100 per hour for tax return preparation" or "I charge $100 to prepare a Schedule D."

Projects

Projects, such as research and development to create a new drug to lower cholesterol.

Organizational Units

Organizational units. What does it cost to run the purchasing department or the human resources department? That would be especially important if an organization is considering outsourcing.

Activities or Processes

Activities or processes, such as credit card authorization or order entry. What does it cost to do a credit card authorization? If it costs you, say, 25 cents to do a credit card authorization, do you really want to do one on a 25 cent or $1 sale, or do you want to have some minimum level?

Distribution Channels

Distribution channels. What does it cost to do an Internet sale versus a retail outlet sale? This particular example comes from Dell, which years ago did an activity-based costing study and decided that Internet sales were more profitable than retail outlet sales and quit doing retail outlet sales. Although Dell has re-entered the retail outlet market, it has not eliminated use of the Internet.

Customers

Customers, such as Wal-Mart. What does it cost to service Wal-Mart? Is Wal-Mart a profitable customer? It is easy to know the sales revenue from Wal-Mart. If the organization can come up with the full cost of servicing Wal-Mart (the cost of goods sold, the shipping, the cost of calling on the customer, the cost of handling its orders, and everything else) the organization can decide how profitable Wal-Mart, or Sears, or some other company is as a customer.

This customer profitability analysis, which requires you to know customer cost, is actually a very interesting area, because studies show that for a lot of companies, 20% of customers provide 80% of the company's profit and another 60% of customers provide another 40% of the company's profit. If you are quick with your math, you are thinking, "Wait a minute, if I've got 80% and then 40%, that's 120%." You can't have more than 100%, and you're right. The remaining 20% of customers will actually eat away 20% of the company's profit; that is, the company is losing money on them. So, doing customer profitability analysis can be a good way to increase your profitability by making sure you treat your good customers well and either make your unprofitable customers profitable or let them go elsewhere.

Cost Pools

Cost pools. Accountants pool the costs together for various cost computations. So, a cost pool is simply a related group of costs that is meaningful to a particular entity. There are many ways to pool costs. Three examples are reviewed here:

Manufacturing Overhead

Manufacturing overhead is a good example. All of the costs of running a factory other than direct materials and direct labor are collectively called manufacturing overhead. All of the manufacturing overhead for the entire factory could be added into one pool.

On the other hand, some companies may accumulate overhead in separate pools for different factory departments, such as assembly and finishing.

Departments

Departments, such as accounting, human resources and shipping, are a common way that companies accumulate their costs and pool them together.

Geographical Regions

Geographical regions, such as the cost of North American operations versus Asian operations. In order for companies to know their profitability by geographic region, they have to have costs broken down that way.

Unit Cost, Average Cost, Marginal and Variable Cost

Unit or Average Cost

In general, the unit cost equals the average cost. That is, you take the total cost for a batch of units of a product and divide it by the number of units produced, which gives you the average cost. So, if a company spent $1,000,000 and made 100,000 units, $1,000,000 divided by 100,000 units is $10 per unit. That is the unit or average cost. You can also compute the average cost for service units produced, such as the average cost of a cable installation at Comcast.

Marginal and Variable Cost

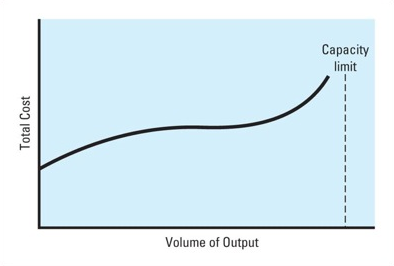

Marginal cost is not an average. It is the cost of providing one more unit of a good or service. We know that the marginal cost is not actually constant; that is, in economics we know that marginal cost is curvilinear, simply meaning a curved line. As shown in Figure 1.1, it looks like a backward "s." Also shown below (Figure 1.2 and 1.3) is how accountants convert the curvilinear marginal cost to a linear cost called variable cost.

Marginal Cost Converted to a Constant Variable Cost

As you can see in Figure 1.1, at very low levels of volume, cost is increasing, but at a decreasing rate.

Now that sounds odd, but here's an example of what is being said. You are buying automobile tires for your tire dealership from a tire manufacturer. Initially, you order 100 tires a month at $100 per tire. As you order more tires, you get a price break. So, when you increase your order above 100 tires a month, you start paying $98 per tire. Your total cost is increasing, but at a decreasing rate of $98 per tire.

At some point, the cost may level off. Assume from 6,000 to 10,000 tires per month, the price is at its lowest at $92 per tire. Above that level point, you start getting diseconomies of scale instead of economies of scale, meaning the cost per unit starts going up at an accelerating rate. So, for example, once you need over 10,000 tires per month, the manufacturer has to work overtime and offers additional tires at $102 each. Now costs are increasing at an increasing rate of $102 per tire. This explains why marginal costs are not constant.

Figure 1.2. Volume of output showing relevant range and Figure 1.3. Volume of output showing capacity limit. Source: Blocher, Stout, Juras, and Cokins, Cost Management: A Strategic Emphasis, 6th Edition, Exhibits 3.5, 3.6, and 3.7, pp. 72–73.

In managerial accounting, we simplify things by assuming we will be on a part of the marginal cost curve that is relatively straight, as shown in Figure 1.2. This results in a linear cost (a straight line) replacing the marginal cost as shown in Figure 1.3. Continuing the tire example, assuming your tire needs are expected to be between 3,500 and 3,600 tires per month, your tire cost will be constant, at say $96 per unit. Note that this is not at the lowest cost per unit, because the relevant range for your tire dealership is not high enough for that.

To distinguish the accounting linear representation from the economics marginal cost, accountants refer to this linear representation of cost as variable cost.

Cost Assignment

Cost assignment is a general term indicating the process of putting costs incurred into cost objects. Now, how do we assign costs? In general, there are two ways we do it: we either (1) trace the cost, or (2) allocate the cost.

Cost Tracing

Cost tracing is the placement of a cost that belongs to only one cost object into that cost object. To the extent that you can trace costs, determining cost is easy. The costs that can be traced are called direct costs, and they are covered in another presentation.

Cost Allocation

Cost allocation is the placement of a cost that belongs to two or more cost objects into those cost objects, which we will do extensively in future lessons. The costs that cannot be traced and, therefore, must be allocated are called indirect costs, and they are covered in another presentation.

Cost allocation involves a numerator and a denominator. The numerator is always money, while the denominator is always some measure of activity. The result of the division is always the amount of the numerator for every one of the denominators.

For example, your manufacturing overhead is $1,000,000 and you produce 100,000 units of a product. For the product cost object, the allocation would be $1,000,000/100,000 = $10 of manufacturing overhead per unit produced.

Product cost object allocation =

Product cost object allocation = of manufacturing overhead per unit produced

Here is an extremely important point about cost allocations that people do not always realize. Numbers look very precise, so if someone says that the product cost for making a particular part is $17.33, people tend to think of that as gospel; but a lot of cost allocations went into that $17.33. If you change how cost allocations are done, it might be $16.05 or $18.10, and these other amounts might be just as correct, that is just as defensible. So, what is the point?

The point is that there is more than one logically defensible way to allocate the same costs to the cost objects. And if there is more than one logically defensible way to allocate the cost, then there is more than one right answer. From the standpoint of an independent observer, the choice between multiple right answers is arbitrary. So, accountants say that all cost allocations are arbitrary.

A simple example is depreciation methods. One company might allocate depreciation of its machinery based on a ten-year life with no salvage value. Another might allocate depreciation on the same equipment based on 1,000,000 units of output. A third organization might allocate it based on a nine-year life with a 10% salvage value. Each time you change how you calculate depreciation or change any of the depreciation assumptions, you will get a different amount of depreciation allocated to each unit of product produced. Which cost per unit is correct? Well, they're all correct as long as your assumptions are reasonable. Notice that your assumptions need to be reasonable. You cannot simply say, "Ah, well, if all cost allocations are all right, I'm just going to use a 10,000-year life for my equipment." Of course, that's not reasonable.

Saying all cost allocations are arbitrary does not mean they are unnecessary. People need a reasonable estimate of cost in order to make decisions. But you want to remember that no matter how precise your costs look when you hand them to people, the number is not the right answer. In fact, if someone says, "The true cost is...", they are misspeaking, because there is no one true cost. At best, all you can reasonably say it that some cost calculations are more accurate than others for the particular decision to be made.

Cost Drivers

Cost drivers. A cost driver is a cause of cost. If you do more of it, it drives your cost up. If you do less of it, it drives your cost down.

Let's review a couple of examples here, just to solidify the concept.

Setup Machines

Setup machines is one example. First, a little background: some companies have crews that go out and set up the machines to make the next batch of product. It can be something as simple as cleaning the paint tank to switch from painting red to painting green. It can be an auto company that is stamping bumpers, changing the dye in the machine so that it can start stamping doors.

What causes the cost? You've got a cost pool called "setup machines" and there's $1,000,000 in it. Where did that $1,000,000 in cost come from?

- Part of it is from the number production runs scheduled. Assuming that each production run requires a set up, then every time you schedule another production run, the setup crew has to go out and change the machine, and that's costly.

- The length of time it takes to do a set-up is another part. A four-hour setup is more costly than a one-hour setup.

- The scheduling of the setups is another factor. If you have your setup crew doing the setups while the facility is in full operation and they have to make production workers stand and wait, that's going to be a more costly setup than if you have the setup crew do the setup while the factory is closed or do the setup on an extra machine that is idle.

- The size and pay rate of the set-up crew affects the cost. If you give your setup crew a 5% raise, everything else held equal, your setups are going to be more expensive than they were before the raise.

- The equipment available for setups and its condition affects the cost. If you're using old forklifts that break down, it's going to affect the time and cost of doing a setup.

Shipping

Shipping is another example. Shipping cost is caused by a number of factors:

- The number or shipments: more shipments cost more money.

- The method of shipment: shipping overnight is more expensive than shipping a five-day delivery.

- The size of the shipment: if you have two boxes that are each ten pounds, and one is a square foot while the other is five square feet, the bigger one is more expensive to ship.

- The weight of the shipment: if you have two boxes that are each two square feet, and one weighs 10 pounds while the other weighs 40 pounds, the heavier one is more expensive to ship.

- The fragility of the shipment: assuming you are packing fragile items more carefully or with more materials to protect them, paying extra insurance for the fragility, or are replacing items that break in shipment, more fragile items are more expensive to ship.

- The size and pay rate of the shipping department staff.

So, there are a lot of things that drive cost.

Now, why are we covering this? If you're going to manage cost at an organization, the first thing you need to do is figure out what is driving that cost.

Let's take this shipping cost, I can look at this list and say, "Wow, we've got all these causes of shipping cost. What should I address first?" You need to ask, "What's the biggest contributor to shipping costs at our organization?" Let's say that you found out that your organization is so behind on customer orders that it is shipping overnight 40% of the time. Then, perhaps you should first address the method of shipment and try to fix the system, so you don't need to use overnight shipping frequently. After you fix the expedited shipping problem, you need to ask, "Now, what's the biggest contributor to shipping costs at our organization?" in order to determine what to work on next. For example, if you have a lot of breakage in shipment, which you have to replace at your cost, you could review how you pack your shipments.

Cost Allocation Bases

This is an extremely important concept, meaning you will use it repeatedly during the rest of the course! Learn it well!

Cost allocation bases are an extremely important subject that any student of managerial or cost accounting must master early in the course. Because there is no single "correct" way to allocate a particular cost, there is no single "right" answer when doing allocation. Still, estimates of cost are needed, making cost allocations necessary.

You should know from your high school math that the top of a fraction is called the "numerator" and the bottom is called the "denominator." The cost allocation base is the bottom or the denominator of the cost allocation fraction. For example, $200,000 manufacturing overhead divided by 10,000 machine hours equals $20 of manufacturing overhead per machine hour. In this case, machine hours are the allocation base.

Cost allocation = of manufacturing overhead per machine hour

Notice that whenever you do a fraction, you're always suppressing the denominator to one and saying how much numerator you have for every one of the denominator. Let's just say that in your hometown there are 1,000 dogs and 100 cats. Well, 1,000 dogs divided by 100 cats is 10 dogs per cat. If you flip it, and put the 100 cats over the 1,000 dogs, it is 0.1 cats per dog. You're always ending up with one of the denominator and saying how much of the numerator there is for that one of the denominator. If you keep that in mind, any fraction you learn is a pretty simple thing.

If you get into financing, you learn the debt-to-equity ratio, which is debt divided by equity. What does it tell you? It tells you the amount of debt for every one dollar of equity. Now you have to know how debt is defined. Is it just long-term liabilities or all liabilities? What do we mean by equity? Is it just stockholder's equity or is it creditor and stockholder's equity? But the point is that the fraction, debt-to-equity, is simply the amount of debt for every one dollar of equity.

We have unit level allocation bases. What do we mean by unit level? The allocation base changes proportionally with changes in production—if production goes up 10%, the base goes up 10%, and if production goes down 4%, the base goes down 4%. It is called unit level because it changes along with the units.

Let's look at three unit-level allocation bases:

Let's look at three unit-level allocation bases:

- Direct labor hours: if you're going to increase production by 10%, then you should need 10% more direct labor hours.

- Direct labor dollars: if you're using 10% more direct labor hours, you're going to pay 10% more in direct labor dollars.

- Machine hours: if you increase production 10%, you're going to need to run the machines 10% longer.

So, these are all called unit level because they vary with the number of units produced. You can also have unit-level allocation bases that vary with the number of units sold. Sales commissions vary with the number of dollars sold, so commissions are unit level with respect to sales revenue.

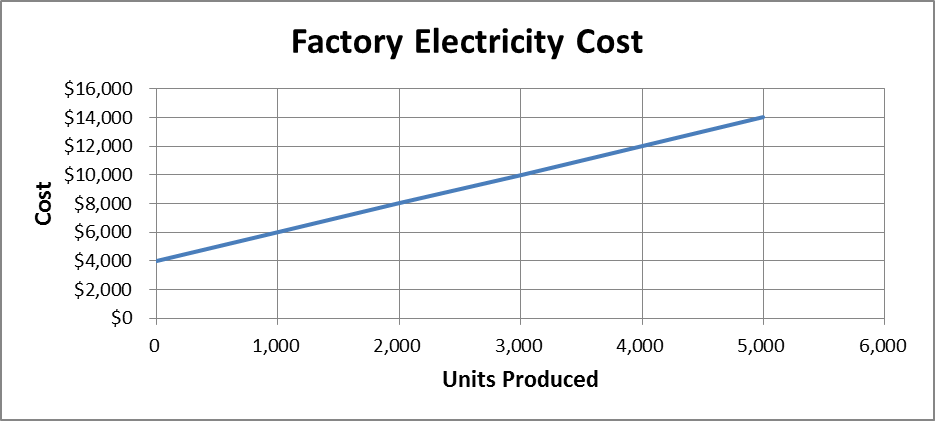

Some costs are unit level. For example, factory machinery electricity is unit level. If you make 10% more units, you run the machines 10% longer and your electric bill is going to go up about 10%. Allocating it based on a unit-level allocation base such as machine hours is logical.

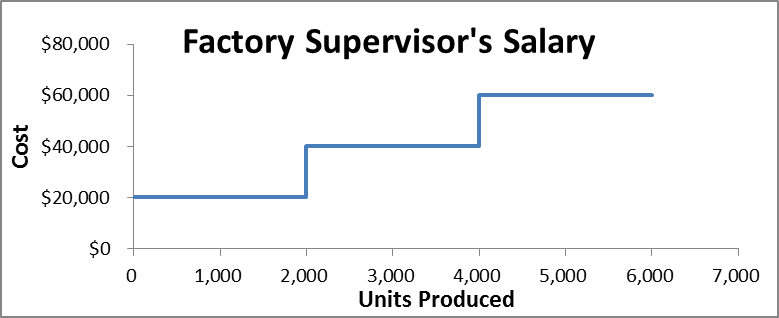

However, a unit level allocation base is often used to allocate costs that do not vary with the number of units produced. Factory building depreciation is not unit level. Allocating it with a unit-level allocation base can lead to misleading cost calculations. For example, your building depreciation is $1,000,000 a year and you make 200,000 units, so you say it is $5 a unit. Well, it is $5 a unit if you make 200,000 units. If you make 100,000 units, it would be $10 per unit. If you make 500,000 units, it would be $2 a unit. When you start using a unit-level allocation base to allocate something that is not unit level, people can start thinking it is unit level and make some very bad business decisions. That's something you need to watch out for in this situation.

Using Cost Drivers for the Allocation Base

For any cost allocation, it's preferable to use a cost driver as the denominator; that is, use a factor that actually causes the particular cost in the numerator to change.

When using a cost driver, focus on the one cost driver considered best suited for allocation. You might allocate "setup machines" cost using the number of setups or the number of setup hours. You might allocate shipping costs using the number of shipments or the weight of shipments, if weight is the most important factor.

When using a cost driver, focus on the one cost driver considered best suited for allocation. You might allocate "setup machines" cost using the number of setups or the number of setup hours. You might allocate shipping costs using the number of shipments or the weight of shipments, if weight is the most important factor.

Something to remember is that the best cost driver for allocating the cost may not be the most important cost driver for managing the cost. You shouldn't forget that other cost drivers exist. For example, you might allocate "setup machines" cost based on the number of setups; however, you might decide that decreasing the time needed to do a setup—setup hours—is the most important cost driver for managing the cost.

Sometimes you cannot use a cost driver to allocate a cost, because there is no cost driver. An example is straight-line depreciation of a factory building, which is based on the passage of time. You cannot logically allocate it using direct labor hours or number of setups or any other denominator that drives the cost, because it is strictly a function of time. We might allocate it based on square footage used by different products, which is logical, but changing the square footage used by any product does not change the depreciation. Where a cost driver is not available, there are other criteria for selecting an allocation base that will be covered in another presentation.

Lesson 1a Summary

You are now familiar with a variety of cost accounting terms. Think about your understanding of each one as we review the list.

- Cost

- Cost objects

- Cost pools

- Unit/average cost

- Marginal and variable cost

- Cost assignment

- Cost tracing

- Cost allocation

- Cost drivers

- Cost allocation bases

If you are not comfortable with any one of these terms, review it again. These terms are fundamental to any study of cost or managerial accounting and any lack of understanding will cause you problems later.

Introduction to 1b: Direct versus Indirect Costs

This lesson discusses the segregation of costs into the mutually exclusive categories of direct and indirect. To do so, you must have a very good understanding of the desired cost object.

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to

- classify costs as direct or indirect with respect to a particular cost object.

Be aware that the distinction between direct and indirect costs is fundamental and is used throughout the study of cost or managerial accounting.

Lesson 1b: Direct versus Indirect Costs | Video

If you choose to watch the video, you may skip the text in lesson 1b and continue to the instructor quiz on direct vs. indirect costs.

Segregating Costs: Direct vs. Indirect Costs

THOMAS BUTTROSS: One of several topics to cover when talking about basic cost concepts is the segregation of costs into direct and indirect costs. The learning objective is to understand and be able to use cost categories, which are segregations of costs that underlie managerial accounting. Be aware that these cost categories are fundamental and are used throughout the study of cost and managerial accounting.

One way to segregate costs is direct versus indirect costs, which is covered here. Another way is fixed versus variable cost, which is covered separately. A third way is the segregation of costs in financial accounting for financial reporting purposes by functional categories, such as separating rent expense from utilities expense from interest expense, which is not covered in managerial accounting.

An important point is that there are different segregations of the same cost for different purposes. Note that these categories are not mutually exclusive. For example, a direct cost can be fixed or variable, and an indirect cost can be fixed or variable.

These methods used to segregate costs apply to all kinds of organizations, as well as to individuals such as you. Any organization that incurs costs, whether it is in manufacturing, merchandising, service, not-for-profit, or government can segregate its costs. All organizations are likely to have some costs that are direct and some costs that are indirect with respect to a particular cost object.

Direct costs are costs that can be traced to one cost object and are material enough to be worthy of tracing. An indirect cost is a cost that cannot be traced to one cost object, meaning it belongs to more than one cost object. Or it belongs to one cost object, but it is not material enough to be worth tracing.

One way to understand direct versus indirect costs is to go through some examples. As you can see here, you have to first define the cost object. If we were talking about a product cost object, direct materials can be directly traced to the product. Each car has around 2,000 pounds of steel, a windshield, seats, and other various components. The direct labor can also be traced to the particular product. As they go down the assembly line, each car uses, say, 11 hours of direct labor.

Indirect costs would include most of the manufacturing overhead. For example, take the plant depreciation. You have to have a plant to build your product, but the plant depreciation cannot be traced to the particular units of product built. So it has to be allocated among the units. The same would be true of the utility bill for the plant, the janitorial services for sweeping the plant, and most of the other costs of operating the plant.

Now consider an accounting department cost object. The salaries of the accountants can be directly traced to the accounting department. The depreciation of computers and office equipment used solely by accountants can be traced to the accounting department.

However, what about the cost of human resources? After all, human resources personnel handle the hiring and termination of accountants, as well as take care of the accountants' employee benefits while employed. The cost of human resources, which also handles the non-accounting departments of the company, would have to be allocated among the various departments that benefit from the use of human resources.

What about the cost of the payroll department? The payroll department pays all the employees. And the cost of running the payroll department would have to be allocated among all the departments benefiting.

Finally, let's take customer. A customer cost object here, numbered as customer 21. We can trace the cost of goods sold to customer 21. That is, we know what merchandise was sold to customer 21. We can trace the shipping to customer 21, assuming we used an outside shipper. That is, we know how much we paid the shipper to take merchandise to customer 21.

The sales commission on sales to customer 21 are also direct. If we sold one million to customer 21 and paid 5% in commissions, the 50,000 sales commissions is clearly traceable to customer 21. Now what if the sales department individuals besides commissions get a salary?

Assume sales staff were paid 2,000 a month, and they called on various customers. So the person who called on customer 21 also called on 30 other customers during the year. We would have to allocate the base salary of the sales individual to the various customers who benefited. And most of the sales department overhead, like the depreciation of the equipment, used by the sales department, would also be indirect and require allocation.

Returning to the shipping example, it would not be direct if the company used its own internal delivery trucks that delivered something to customer 21, and then continued down the highway and delivered something to customer 22. Then delivery expense would be an indirect cost.

The cost object is a key. That is you have to define the cost object before you can determine whether a cost is direct or indirect because you have to ask yourself, direct or indirect with respect to what. The cost that is direct with respect to one cost object can actually be indirect with respect to a different cost object. So you can't just memorize the handling of a particular cost. For example, it is incorrect to make a statement like, "The depreciation of the plant is always indirect."

Let's take a product example, the salary of the plant manager. If the cost object is the plant, then the salary of the plant manager is directly traceable to the cost object. If the cost object is one of several products made in the plant, and the plant manager oversees the entire plant, the plant manager is indirect with respect to the individual products. And the salary would have to be allocated among them, if you choose to allocate the salary. What if the plant makes only one product? If the plant makes only one product, the salary of the plant manager would be directly traceable to that product.

Now, take a service example, the salary of an accountant. If the cost object is the accounting department, that is you're trying to keep track of the cost of running your accounting department, the salary of an accountant is directly traceable. If you're trying to determine the cost of having a human resources department, human resources does need the accounts to keep the financial records involving human resource salaries and other human resource department costs, you cannot trace the accountant's salary to the human resources department. A certain amount of the accountant's salary could be allocated to running the human resources department.

Put another way. If you close down, that is outsource human resources, at least in theory, there would be a little less accounting to do. And as you outsource departments, you might be able to reduce the number of accounts you need. Again, do not just memorize. Review the particular situation. If you have an accountant whose only job is to keep records for human resources, that accountant's salary would be directly traceable to the human resources department.

Here's an opportunity for you to make sure you understand direct versus indirect costs. Classify each of the following costs with respect to a purchasing department cost object. That is, you want to determine the cost of running the purchasing department.

The purchasing department has its own building. Is depreciation on the building direct or indirect? Pause the recorded presentation until you have a solution. If you say direct, you are correct. Because purchasing has the entire building, all of the depreciation is directly traceable to purchasing.

Purchasing has several purchasing agents. Is the salary of a purchasing agent direct or indirect? Pause the recorded presentation, until you have a solution. If you say direct, you are correct. Because a purchasing agent works full time in the purchasing department, the agent's salary is directly traceable to purchasing.

What about office building utilities, where purchasing uses approximately 10% of the building space? Pause the presentation, until you have a solution. If you said indirect, you are correct. In this case, the utilities benefit the entire building, which includes other departments.

You might say because purchasing is 10% of the space, they surely used 10% of the utilities, so you can trace it. Well, you don't know how much purchasing really uses. Maybe the people in the other 90% of the building like it cooler, and turn their air conditioning down more. Or maybe the purchasing people work later than everyone else and, therefore, have their lights on more and use more than 10% of the electricity.

In all likelihood, one would allocate to purchasing 10% of the utility bill, based on the square footage used by purchasing. While allocating based on square footage is a normal way to allocate utilities, never forget that it is still an allocation. This is the end of the discussion of direct versus indirect cost.

Direct vs. Indirect Costs: One Way to Segregate Costs

One way to segregate costs is direct versus indirect costs, which is covered here. Another way is fixed versus variable costs, which are covered separately. A third way is the segregation of cost in financial accounting for financial reporting purposes by functional categories such as separating rent expense from utilities expense from interest expense, which is not covered in managerial accounting. An important point is that there are different segregations of the same cost for different purposes. Note that these categories are not mutually exclusive. For example, a direct cost can be fixed or variable and an indirect cost can be fixed or variable.

Segregating Cost Overview

These methods used to segregate costs apply to all kinds of organizations (as well as to individuals such as you). Any organization that incurs costs—whether it is in manufacturing, merchandising, service, not-for-profit, or government—can segregate its costs. All organizations are likely to have some costs that are direct and some costs that are indirect with respect to a particular cost object.

Direct versus Indirect Costs: Defined and Examples

Direct costs are costs that can be traced to one cost object and are material enough to be worthy of tracing. An indirect cost is a cost that cannot be traced to one cost object, meaning it belongs to more than one cost object. Or it belongs to one cost object but is not material enough to be worth tracing.

Examples

One way to understand direct versus indirect cost is to go through some examples. As you can see here, you have to first define the cost object.

If we are talking about a product cost object, direct materials can be directly traced to the product. Each car has around 2,000 pounds of steel, a windshield, seats, and other various components. The direct labor can also be traced to the particular product. As they go down the assembly line, each car uses, say, 11 hours of direct labor.

Indirect costs would include most of the manufacturing overhead. For example, take the plant depreciation. You have to have a plant to build your product, but the plant depreciation cannot be traced to the particular units of product built, so it has to be allocated among the units. The same would be true of the utility bill for the plant, the janitorial services for sweeping the plant, and most of the other costs of operating the plant.

Now, consider an accounting department cost object. The salaries of the accountants can be directly traced to the accounting department. The depreciation of computers and office equipment used solely by the accountants can be traced to the accounting department. However, what about the cost of human resources? After all, human resources personnel handle the hiring and termination of accountants, as well as take care of the accountant's employee benefits while employed. The cost of human resources, which also handles the non-accounting departments in the company, would have to be allocated among the various departments that benefit from the use of human resources. What about the cost of the payroll department? The payroll department pays all the employees and the cost of running the payroll department would have to be allocated among all the departments benefiting.

Finally, let's take a customer cost object, here numbered as Customer 21. We can trace the cost of goods sold to Customers 21; that is, we know what merchandise was sold to Customer 21. We can trace the shipping to Customer 21, assuming we used an outside shipper; that is, we know how much we paid the shipper to take merchandise to Customer 21. The sales commissions on sales to Customer 21 are also direct. If we sold $1,000,000 to Customer 21 and paid 5% in commissions, the $50,000 in sales commissions is clearly traceable to Customer 21.

Now, what if the sales department individuals, besides commissions, get a salary, Assume sales staff are paid $2,000 a month, and they call on various customers. So, the person who called on Customer 21 also called on 30 other customers during the year. We would have to allocate the base salary of the sales individual to the various customers who benefited. And most of the sales department overhead, like the depreciation of the equipment used by the sales department would also be indirect and require allocation. Returning to the shipping example, it would not be direct if the company used its own internal delivery trucks that delivered something to Customer 21 and then continued down the highway and delivered something to Customer 22. Then, delivery expense would be an indirect cost.

Direct vs. Indirect Costs: Cost Objects—A Key

The cost object is a key. That is, you have to define the cost object before you can determine whether a cost is direct or indirect, because you have to ask yourself, "Direct or indirect with respect to what?" A cost that is direct with respect to one cost object can actually be indirect with respect to a different cost object. So, you can't just memorize the handling of a particular cost. For example, it is incorrect to make a statement like, "The depreciation of the plant is always indirect."

Let's take a product example: the salary of the plant manager. If the cost object is the plant, then the salary of the plant manager is directly traceable to the cost object. If the plant makes only one product, the salary of the plant manager would also be directly traceable to that product. If several products are made in the plant and the plant manager oversees the entire plant, the plant manager is indirect with respect to the individual products and the salary would have to be allocated among them, if you choose a product cost object.

Now, take a service example, the salary of an accountant. If the cost object is the accounting department—you are trying to keep track of the cost of running your accounting department—the salary of an accountant is directly traceable. If you are trying to determine the cost of having a human resources department (human resources does need the accountants to keep the financial records involving human resource salaries and other human resource department costs) you cannot trace the accountant's salary to the human resources department. A certain amount of the accountant's salary could be allocated to running the human resources department. Put another way, if you closed down, that is, outsourced human resources, at least in theory there would be a little less accounting to do and as you outsource departments you might be able to reduce the number of accountants you need.

Again, do not just memorize. Review the particular situation. If you have an accountant whose only job is to keep records for human resources, that accountant's salary would be directly traceable to the human resources department.

Direct vs. Indirect Costs: Classification Practice

Here's an opportunity for you to make sure you understand direct versus indirect costs.

Classify each of the following costs with respect to a purchasing department cost object. That is, you want to determine the cost of running the purchasing department.

Introduction to 1c: Product versus Period Cost

This lesson discusses the segregation of costs into the mutually exclusive categories of product versus period. All organizations that have any costs have period costs. Product costs only exist for those organizations that build their own inventory.

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to

- distinguish between manufacturing, merchandising, and service firms; and

- describe the difference between product costs (inventoriable meaning asset) and period costs (expenses).

Lesson 1c: Product vs. Period Costs | Video

If you choose to watch the video, you may skip the text in lesson 1c and continue to the instructor quiz on product vs. period cost.

Segregating Costs: Product vs. Period Costs

THOMAS BUTTROSS: A manner of segregating costs that only applies to manufacturing companies is product, or period, costs. In order to do the segregation of costs, you need to understand the difference between manufacturing, merchandising, and service firms. Then you'll be able to understand the difference between a product cost, which is a cost that goes into inventory on the balance sheet, and a period cost, which is a cost that goes into expenses on the income statement.

This presentation is only for manufacturers. That is, the product cost category only applies to companies that build their inventory. Period costs apply to all companies, since these are primarily the operating expenses on any income statement.

A manufacturing organization is one that buys raw materials and builds its inventory and then sells the inventory that it built. Therefore, these organizations will have three separate inventories among their current assets on the balance sheet. They will have raw materials, which are goods awaiting use in production, that is waiting to be used inside the factory. They will have work in process, an account for the partially completed units inside the factory. And they will have finished goods, which are units that have been completed and are awaiting sale to the customers.

Merchandisers, on the other hand, do not build anything. They buy finished goods and sell them. They add what economists call place utility. By having a Toyota dealership in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, it saves you from having to make a trip to the factory to pick up a Toyota.

Merchandisers have one inventory, which is the manufacturer's finished goods. But instead of calling it finished goods, it is generally called merchandise inventory.

Since they provide a service and do not sell goods, service companies technically do not have an inventory. However, they might have a parts or supplies inventory, which they might call parts or supplies or they may call inventory. If they do carry parts or supplies, it is not considered an inventory on the level of a merchandiser.

A company can have more than one type of business. For example, an automobile dealer carries a large inventory and sells to the public as well as uses it internally. The parts department is a merchandiser, and the repair shop is a service business. As another example, Sears is a large merchandiser. Several of its stores also have service centers for appliances, equipment, and automobiles.