ACCTG405:

Lesson 1: Introduction to Taxation and How to Research

Lesson 1 Overview

Welcome to Principles of Taxation. In this lesson, we will learn how it all got started. We will be looking at the birth of taxation in the United States and how we got to the point where we are now. Who makes these laws, anyway? And what is the IRS? We will also learn about other taxes besides individual federal income taxes. Finally, we'll cover how to navigate tax authority for purposes of research and how to present this information in a professional tax memo. Let’s get started.

Learning Objectives

After you have completed this lesson, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the history of the federal tax system in the United States.

- Explain how tax law is created.

- Describe the functions of the Internal Revenue Service.

- Explain the different types of taxes that are used to collect revenue.

- Define and calculate taxable gifts for federal purposes.

- Explain how to conduct tax research and prepare a tax memo.

Lesson Readings & Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

Federal Income Tax System

Remember when you learned about the Boston Tea Party back in elementary school? That’s where it all started. The colonists revolted against unfair taxation without representation. When they won their independence, they wanted to make sure that there would be no more unfair taxation. So what did they do? They wrote it into the U.S. Constitution—namely, in Article I, Sections 2 and 8:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers. (U.S. Const. art. I, § 2)

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States. (U.S. Const. art. I, § 8)

The taxes referred to in these two sections are concerned with property taxes and not income taxes. For the most part, the United States federal government imposed an income tax only when in need of revenue to support the military during times of war. During the Civil War, the U.S. government imposed a 3% tax on income over $600, which to us isn’t a lot—about $80,000 in terms of today’s dollar. That would be like only taxing income above $80,000 today. Could you imagine? It is a dream. These taxes were used to fund the war, and after the war, they were essentially eliminated until the late 1800s when Congress imposed a federal income tax that was not apportioned by the state population (as stated in the Constitution). Needless to say, it was challenged in the courts.

In the 1895 case of Pollock v. Farmers Loan and Trust Company, the court ruled that a tax on rent or income from real estate is a direct tax, because “the whole beneficial interest in the land consisted in the right to take the rents and profits” (as cited in Eddlem, 2013).

The Supreme Court found this income tax to be unconstitutional, but if this is true, then why are we paying individual income taxes in the United States? What do you do to make something Constitutional? That’s right: Create an amendment to the Constitution. And so, in 1913, the 16th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified as follows:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration. (U.S. Const. amend. XVI)

So there it is. Now Congress and the president have the power to create tax law. The first tax return was due on March 1, 1913.

How Is Tax Law Created?

With the constitutional ability to create income tax law, Congress immediately began. Many times people seem to think that it’s really the Internal Revenue Service behind all of the taxes and tax law, but it's not. Let’s review how a federal law is made with an oldie but a goody in Video 1.1. You may know this one.

That is how it's done. Tax law is created just like any other federal law. Figure 1.1 shows the process in a flowchart to help you grasp how tax law originates and progresses to its final passage.

Adapted from "Writing and Enacting Tax Legislation" by the U.S. Department of Treasury, 2010. Retrieved from https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/faqs/Taxes/Pages/writing.aspx

The following process describes the flowchart in Figure 1.1 in a little more detail:

- To begin, the Department of Treasury drafts recommendations for tax laws from the president.

- Because all laws must originate in the House of Representatives, the Department of Treasury presents its recommendations to the House Committee on Ways and Means. This committee then creates what is known as the “House version” of the tax law, which it presents to the entire House of Representatives for a vote.

- With a vote, the House of Representatives passes its version of the tax law.

- The House version goes to the Senate Finance Committee. Two things can happen from here:

- Either the committee agrees with the House version and sends it to the Senate for a vote, or

- the committee makes amendments to the House version and sends the amended version to the Senate for a vote.

- With a vote, the Senate passes its version of the tax law:

- If it's the same as the House version, then it goes to the president to sign.

- If it's the amended version, then a Conference Committee is appointed to merge the two bills. This committee is made up of members from both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

- The Conference Committee modifies both bills into a single one that's likely to get the most votes from each house.

- With a vote, both the House and Senate pass the newly revised bill.

- Finally, the president signs the bill into tax law.

And that's the rest of the story. It was the acts of the Congresses and presidents over the past 100 years that have created the tax law as it stands today. The Internal Revenue Service doesn't come into it until the tax law is already ratified by Congress and the president. The Internal Revenue Service doesn't make the law, but it does organize and police it so that average taxpayers can pay their taxes and that those who don’t are identified.

The Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the agency of the Department of the Treasury of the U.S. government that takes responsibility for administering the U.S. tax law. It was created during the Civil War to help collect the income tax imposed to fund the war. However, it rose to its current prominence with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. The IRS is charged to do two things:

- Create the Internal Revenue Code.

- Police the tax law.

Create the Internal Revenue Code

The IRS creates and maintains the codification of tax law. When Congress creates a law, it isn’t organized and outlined for research purposes and easy reading. One of the roles of the IRS is organizing the law so that like subject matters are grouped together and properly coded for ease of research and citation.

You'll see the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) very soon when we look at tax research. Here is more information on the tax code itself.

In 1954, the tax law was codified to organize its specific laws for easier reference. Up to that point, laws were simply written. In order to find a statement pertaining to a certain tax issue, an attorney might have to read the entire document because there was no system in place to categorize the laws. (Some laws are thousands of pages long!) With minor changes made each year, the 1954 Code remained relatively stable until 1986.

In 1986, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86) brought major changes to the IRC, which significantly changed the way individuals were taxed and set forth precedents that remain in effect today.

In 2001, the Bush Tax Act set forth incremental changes in the law that focused on tax savings for people who created jobs or positively impacted the U.S. economy. Because most of those people were wealthy, this act has been described as favoring the rich while penalizing the middle class.

In December 2017, the most sweeping tax reform since TRA86 became law. The new law signed by President Trump, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, significantly changed the tax law for both businesses and individuals. You will be learning this new law and its application throughout this coming semester.

As you can see, tax law changes continuously, and it is mandatory that tax professionals keep current on a daily basis—and sometimes even that isn't enough.

Police the Tax Law

The IRS, for the most part, helps law-abiding citizens report their information correctly so that they act in accordance with the law. However, the IRS is also charged with making sure citizens who are not following the law are identified and penalized.

In this course, we're focusing on individual (not business) taxes, so consider the federal income tax form that you complete each spring. The IRS created that form and others to make sure individuals report their tax information according to the law. After you submit your form, the IRS is responsible for making sure you, in fact, followed the law. As a part of this process, the IRS conducts audits when clarification is necessary or when it appears a taxpayer has not followed the tax law.

Audits are a part of the required enforcement responsibility of the IRS and are something most taxpayers fear. However, most IRS audits are not scary at all. Here are the different types of audits the IRS conducts.

Correspondence Audit

This is the most common type of audit. It occurs when the IRS finds a small discrepancy on a taxpayer’s tax return. The IRS notifies the taxpayer by letter to request information to resolve the issue. The taxpayer then responds by mail either to provide the information or to make further clarification. It's through this correspondence that the IRS and taxpayer resolve the issue, with the taxpayer possibly receiving a refund, paying additional tax, or having no change made to the tax amount.

Office Audit

This is an audit conducted at the taxpayer's IRS regional office. This type of audit is usually conducted when more information is needed than the IRS can resolve by mail. A face-to-face meeting is then conducted at the IRS regional office to resolve the issues.

Field Audit

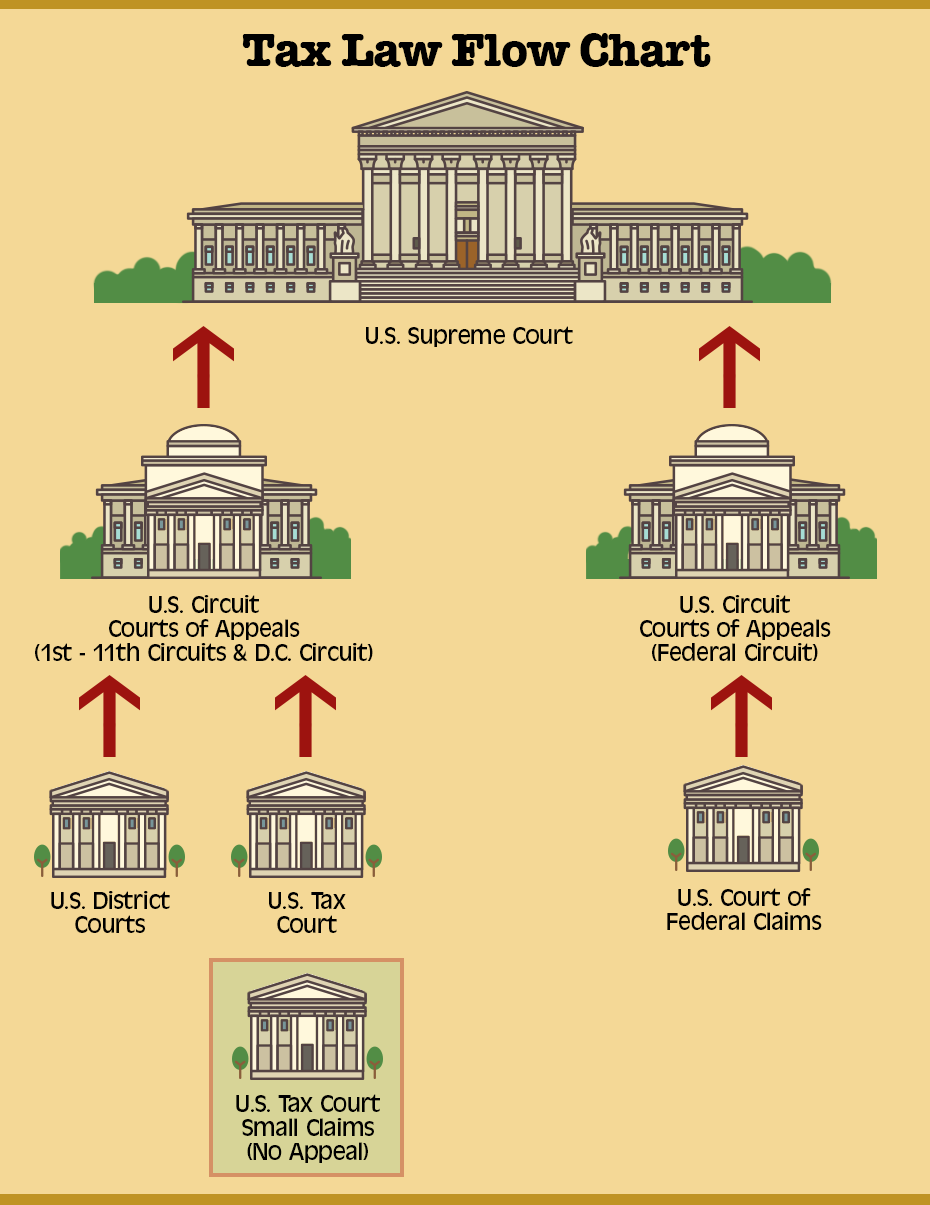

This happens when the IRS needs to look at significant items on the tax return and requires the audit to be conducted at the taxpayer’s residence or place of business. When an office or field audit is completed, the internal revenue agent prepares a report of the audit's findings. If the taxpayer doesn't agree with these findings, then they have a legal remedy by disputing them in tax court. There are different tax courts where a taxpayer can file a lawsuit, as well as different levels of appellate courts. Some cases may even make it to the Supreme Court.

Income Tax Disputes in Court

Figure 1.2 shows the courts used for federal income tax disputes. Note that there is a court of small claims where taxpayers who have small issues to resolve can plead their cases. Decisions that have been made through the small claims court may not be appealed to a higher court, however.

Remember that the IRS is like the police of the tax law, which means it isn't the final word. The federal tax system works the same way traffic law does: Whether you disagree with a speeding citation or an IRS audit, you can go to court to have it resolved.

So, now that you know how tax law is created by the federal government and administered by the IRS, what other types of taxes are there?Other Taxes

What other taxes are there besides the federal income tax? Let’s take a look. They tend to fall into a few basic categories—specifically

- state and local income taxes,

- ad valorem taxes,

- sales tax,

- payroll taxes,

- excise tax,

- estate and inheritance taxes, and

- gift tax.

Let’s take a look at each one and see how they work.

State and Local Income Taxes

Certain state and local income taxes are administered by the state and local governments and can be computed in different ways. Some follow the same system as the federal income tax and some have their own system. There are even states that have no income tax at all: Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, Wyoming, New Hampshire, and Tennessee. Local taxes work in the same way. State income taxes fund the state government, while local income taxes fund the local governments.

Ad Valorem Taxes

An ad valorem tax is placed on the value of an asset a person owns. There are traditionally two types of ad valorem taxes: personal property and real estate.

Personal property tax is placed on the value of an asset that is not real estate, such as automobiles, stock, bonds, boats, and so on. The tax is usually computed by multiplying the fair market value of the property by a set percentage. Some states that don’t have an income tax (e.g., Florida) may have a personal property tax instead. Other states have an income tax as well as a personal property tax.

Real estate tax is placed on the value of real estate property. It's usually assessed by the state and local governments and, like personal property tax, it's calculated by taking a set percentage and multiplying it by the fair or assessed value of the property. Ad valorem taxes usually fund state and local governments.

Sales Tax

There is no federal sales tax (yet!). Instead, sales tax is imposed by state and local governments as another way to collect revenue. Different states tax different items at different rates, and it is usually assessed when the item is purchased by the ultimate consumer. For example, Pennsylvania currently taxes most nonnecessity goods at a rate of 6% applied at the cash register. Five states don’t have a sales tax—Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, Oregon, and Alaska—but Alaska's local municipalities may impose one. People who live in sales tax states may try to avoid paying sales tax by purchasing items (especially large-ticket items) in non-sales-tax states to save money.

What is so wrong about that? Well, if the consumer brings it back to their resident state to use, and if there would have been sales tax on that item if purchased in the resident state, then the consumer is expected to pay that state a sales tax on the item—called a use tax. If they don’t, they may be subject to fines and penalties, and possibly an audit, too. This is becoming very prevalent with online sales transactions. Taxpayers usually pay use tax on items when filing their state tax returns or by filling out a special form, depending on the location.

Learn more about Internet sales tax in the article Internet Sales Tax: A 50-State Guide to State Laws, by Diana Fitzpatrick.

Payroll Tax

You may remember payroll tax from your prior Introduction to Accounting course. If you have a job, your employer is required to withhold taxes from your wages. But employers are also required to pay taxes based on your wages! Why? Because the taxing authority says so!

Employers assume the burden of these taxes and calculate them as part of your annual compensation package. So what are these payroll taxes?

FICA

The Federal Insurance Contribution Act (FICA) is comprised of two taxes: Social Security and Medicare. The federal government states that each employee must contribute to these benefit plans and that the employer must also contribute on behalf of the employee. The taxes are applied to the employee's annual wages, and the Social Security portion of the tax has a maximum limitation.

For Social Security,

- employers pay 6.2% of gross wages up to the annual limitation per employee, which changes each year, and

- employees pay 6.2% of gross wages up to the annual limitation, which changes each year.

For Medicare,

- employers pay 1.45% of gross wages with no limitation per employee, and

- employees pay 1.45% of gross wages with no limitation.

- If earned income including self-employment income is above a certain level for a taxpayer or taxpayers (determined by filing status)

- individuals will pay an additional 0.9% Medicare tax on gross wages and

- individuals will pay an additional 3.8% Medicare tax on net investment income.

A self-employed taxpayer must pay both the employer and the employee parts of FICA taxes.

SUTA

The State Unemployment Tax Act (SUTA) is imposed by the state in which the employee resides and is used to fund the state unemployment system. Usually, only employers are required to pay this tax based on a certain amount of the earnings of each employee.

FUTA

The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) is paid by the employer to help fund state unemployment benefits. This tax is computed on the first $7,000 of each employee's gross wages at 0.6% each year.

Excise Tax

Excise taxes are imposed by the federal, state, and local governments, and the most well-known is on gasoline. The gas tax in particular is usually imposed by both federal and state governments, and different states, of course, have different rates. Like sales tax, this tax is usually added to the price per gallon seen at the gas pump.

Other types of excise taxes are applied to alcohol and tobacco products, gambling revenues, and even your cell phone bill. If you're starting to see a pattern here, it's no coincidence. Most people call this the “sin tax” because it's placed on items that the government may not want consumers to use, at least not in excess. Therefore, these items get taxed additionally to raise the cost and, possibly, discourage purchases. Although excise taxes are usually built into the price of the item at purchase, some are added afterward (e.g., hotel excise taxes).

Estate and Inheritance Taxes

The federal government only taxes estates, not inheritances. But what's an estate? According to the IRS, an individual's "gross estate includes all property in which the decedent [individual] had an interest (including real property outside the United States)" at death (Internal Revenue Service, 2017). The estate tax comes into play when the person dies, at which time federal taxes must be paid on whatever assets the person owned at death. If you're reading carefully, right about now you're probably thinking, "Wait, a person even pays tax at death?" And the answer is yes—sort of. Estate taxes can be a complex area.

In general, people who have estates in excess of $5.6 million at death would have to pay a federal estate tax. In addition, their state of residence might require payment, too. Some states have estate taxes due at death just like the federal government; however, other states only assess an inheritance tax.

If, according to Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary (n.d.), an inheritance is "money, property, etc., that is received from someone when that person dies," then an inheritance tax is the amount the government expects from the person receiving inherited property. The inheritor is responsible for paying the required inheritance tax, which is usually imposed at a rate based on the inheritor's relationship to the deceased. The closer in relationship, the lower the tax rate, so that in most states, property passed from one spouse to the other escapes tax entirely.

Learn more about which states impose different taxes in the article State Tax Chart: Which States Collect Income Taxes, Sales Taxes, Death Taxes and/or Gift Taxes?, by Julie Garber.

Let's go back to that question from earlier: Does a person have to pay taxes at death? Sort of—depending on the tax. Remember it this way:

- Estate taxes are assessed on the person who died for the right to give the assets away.

- Inheritance taxes are assessed on the recipient of property at the death of another person for the right to receive that property.

Gift Tax

One last tax we need to look at is gift inter vivos, or gift tax. It's one that people sometimes wonder about and don’t really understand. It's unusual because it taxes not the recipient of the gift but the donor, and because not all gifts are taxed. Because it's usually a federal tax, we'll focus on the federal version here, but be aware that some states are starting to impose gift taxes, as well. It's covered in more detail on the next page because it's a little more complicated than the others! So let's move on to understand more.

![]()

These are some of the common types of taxes assessed at the federal, state, and local level, which are all used to fund the various government levels.

Gift Tax

The IRS defines a gift inter vivos in the definition of gift tax.

The gift . . . is . . . the transfer of property by one individual to another while receiving nothing, or less than full value, in return. . . . You make a gift if you give property (including money), or the use of or income from property, without expecting to receive something of at least equal value in return. If you sell something at less than its full value or if you make an interest-free or reduced-interest loan, you may be making a gift (Internal Revenue Service, 2016).

By this definition, gifts inter vivos include

- property (including money) or the use of or income from property that one person gives to another person without expecting to receive something of at least equal value in return,

- the difference between the market value and the sale price of something that is sold at less than its full value, and

- the amount of interest that should have been charged and paid to someone who makes an interest-free or reduced-interest loan.

What Constitutes a Gift?

In contrast, some items are not considered gifts and therefore are not taxable. Most of the items listed above are self-explanatory but must be followed carefully—for instance, in the following ways:

-

Tuition or medical expenses: Tuition and medical expenses must be paid directly to the institution. The amount cannot be paid to an individual to pay the expenditure him- or herself.

-

Gifts to your spouse: Gifts to a spouse must be given to a spouse that is recognized under federal tax law, which includes same-sex marriages. There are several rules concerning alien (non-U.S. citizen) spouses.

-

Gifts to a political organization for its use: Gifts to political organizations must be made directly to the organization, not to a specific candidate.

-

Gifts to charities: Gifts to charities may seem simple, but the charity must be recognized by the IRS as a qualified charity adhering to the rules of not-for-profit organizations.

-

Annual gifting exclusion: The annual exclusion is an annual amount that each taxpayer is allowed to give per recipient before incurring a gift tax and is the most important rule to remember.

This law allows each taxpayer to gift a certain amount each year to as many recipients as the taxpayer wants. In English, that means that with the current annual exclusion set at $15,000, you can give each person in the world $15,000 each year without incurring any gift tax. However, if you give any one person $16,000, then you will have to report a taxable amount of $1,000 because you've exceeded the limitation. It doesn't matter if you give one person $13,000 and another person $16,000—you cannot average the amount between the recipients. You still have to pay tax on that $1,000 difference.

Ultimately, a gift follows these three primary rules:

- It is irrevocable—you cannot take it back.

- It is not an exchange of services or goods. That is a trade or a sale and may be taxable.

- It has no strings attached—you cannot include any instructions in the way the gift must be used.

At Thanksgiving dinner, Mason announced that he and his husband Kendall are buying a house. Mason's mom and dad, Sharla and Carl, want to give them $20,000 to help with the purchase. Will they be taxed on the $6,000 that exceeds the $15,000 annual exclusion? Actually, that depends on the details. Sharla and Carl have several ways to structure the $20,000 gift so that it isn't considered a tax event:

- Sharla and Carl can gift $15,000 this year at Christmas, and the rest ($5,000) next year when Mason and Kendall make their down payment in order to split the gift across tax years.

- Sharla can give Mason $15,000 and Carl can give the remainder ($5,000).

- Sharla and Carl can give $15,000 to Mason and the remainder ($5,000) to Kendall.

Despite the confines of gift tax law, there are still legal ways to work for the best interest of the family without incurring additional taxes.

Unified Credit

The value of gifts that a taxpayer gives to each person is tracked during the year. If the total of the gifts to an individual in a year exceeds the annual exclusion amount, the IRS will tax the excess at the gift tax rate. At least that's usually the case, but taxpayers may be able to reduce or eliminate gift taxes each year completely through the unified credit: a joint credit for gift and estate taxes.

To understand the unified credit, think back to the estate tax. As you may remember, only estates valued over $5.6 million are subject to estate tax. Why $5.6 million? Because that's the deduction allowed for computing estate taxes. The unified credit allows taxpayers to reduce the value of any gifts they grant while alive by preemptively applying this $5.6 million estate tax deduction to the gifts as credit. In this way, they can eliminate taxable gifts during their lifetime and consequently also gift taxes. In addition, taxpayers can opt to use the $5.6 million unified credit to pay any gift taxes that exceed the annual exclusion each year. Because gift tax rates are 40% at their highest level, most taxpayers opt to use a portion of the $5.6 million deduction now in order to reduce gift taxes on taxable gifts over their lifetime.

So, what happens to taxpayers who use up all $5.6 million of this deduction in gift tax credits during their lifetime? At death, their deduction would be $0.00, and their estate would be taxed without the deduction. Eventually, the taxpayer always pays tax on transferred items, be they gifts during their lifetime or an estate at death.

Read on for an example of this very interesting integrated taxing system (gifts and estates).

Unified Credit Example

Let's look at a comprehensive example illustrating how the unified credit works with taxable gifts.

Arthur is a wealthy man who would like to reduce his estate before he dies. He is aware of the rules regarding estate taxes and gift taxes and wants to make certain he transfers as much of his wealth to his family as possible while paying minimal tax. He is married, and the current fair market value (FMV) of his assets is $12,000,000. Where do we start?

Well, we know that, thanks to the estate tax deduction, the total he can get rid of tax-free is $5.6 million through regular transfers.

Some simple subtraction tells us that $12,000,000 - $5,600,000 = $6,400,000. So what do we do with the rest? The following might be good options.

Transfer to Spouse

Since Arthur is married, his spouse might own half of his property depending on how it's titled. But what if she doesn't? Arthur should consider transferring assets into his spouse's name. (Unless there's some reason he doesn't want to: Pending separation? Much younger spouse? Gold-digger issues? Too naïve and trusting?)

Besides putting his spouse's name on property titles, Arthur can also transfer money to his spouse. But how much? Remember that she's also allowed to transfer $5.6 million tax-free when she dies, so it would make sense to transfer up to that amount to her as long as Arthur trusts her. This means that of his $12 million estate, he can transfer $5.6 million of the remaining $6.4 million to his wife with no gift or estate tax implications.

Time for some more subtraction: $6,400,000 - $5,600,000 = $800,000. We've come a long way, but that's still quite a bit for Arthur to pay taxes on. Unless there's some other way to avoid them.

Gifting and Tuition Options

Let's look at Arthur's family members and their pending events.

Thanks to the annual exclusion, Arthur can gift $15,000 to each of his family members each year tax-free—and so can Arthur's wife, for a total of $30,000 to each family member per year, none of which would be taxable.

In addition, Arthur can make payments to cover medical expenses and educational expenses for his family, and as long as he pays the institution directly, those gifts wouldn't be taxable either. So Arthur should consider paying for his children's education and medical bills and the education and medical bills of his grandchildren or other family members. He could even pay for nonfamily members, too.

Let's assume that Arthur is maximizing his gifts and finds that he will still have a taxable estate. What do we do in this case?

Donations

As Warren Buffett and Bill Gates have realized, they would prefer to give their hard-earned income to organizations that reflect their personal beliefs rather than give it to the IRS. Arthur should consider a clause in his will that provides for charitable gifts to be made with the remainder of his wealth, thus eliminating taxation on his estate. In this way, Arthur has been able to maximize his family wealth and minimize taxation.

Remember that when Arthur passes away, the executor of the estate will assess the value of his assets and subtract any unified deduction that remains after deducting the taxable portion of gifts he gave throughout his life. It's that final amount upon which estate taxes would be imposed. These rates can reach 40% on an estate.

While wealth transfer is not part of this course, it's an important topic for all accountants to study because everyone has an estate, and each estate's structure can impact the individual income tax of its beneficiary. Also, clients will come to you for advice on whether to gift now or wait to pass along their assets at death.

Now that we have covered the different types of taxes, it's time to look at the research process and the end result: a memo to file and a letter to the client.Tax Research

Now that you have an idea of the different types of taxes, it's time to look at how to find specific tax law to support the way that you, the tax preparer, handle a tax question or situation. Remember from prior discussion that there are many different areas where you can look for answers and guidance for handling taxes or deductions on a tax return.

Therefore, it's imperative for you to understand the process for locating the resources necessary to properly analyze each scenario you'll encounter throughout this course. Please review the three parts to the tax research process, which is what should go into conducting a successful search of tax sources:

- Primary tax code, which is the strongest evidence to support a tax position.

- Court system and tax treaties, which is more evidential material used to support a tax position.

- Steps to complete and write the tax research memo and letter to the client.

Primary Code Sources

The following primary code sources will be important as you research:

Internal Revenue Code

The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is located in Title 26 of the U.S. Code. The format of the Code is rather important to understand. Income Taxes is under Subtitle A.

The code is broken down as follows:

- Title

- Subtitle

- Chapter

- Part

- Section

- Subsection

- Paragraph

- Subparagraph

- Paragraph

- Subsection

- Section

- Part

- Chapter

- Subtitle

![]() To navigate the slide viewer below, click on the successive gray dots or arrows to move to a new slide.

To navigate the slide viewer below, click on the successive gray dots or arrows to move to a new slide.

Regulations (REG)

Revenue Rulings (REV RUL)

Revenue Procedures (REV PROC)

Letter Rulings (LTR RUL)

Court System and Tax Treaties

Tax Court

- Federal trial court of record established by Congress under Article I of the U.S. Constitution, section 8

- Both parties present evidence to a single judge without rebuttal.

- Taxpayer not required to pay tax prior to filing

- Must file tax return within 90 days of receiving notice from IRS

- Tax decisions not bound by U.S. District Court or U.S. Court of Federal Claims decisions

- Tax Court must follow decisions of U.S. Supreme Court

Tax Decisions

- Tax Court decisions are binding only to the Tax Court.

- No other court is required to accept decisions of the Tax Court.

- There are three types of decisions issued by the Tax Court:

- reported,

- memorandum, and

- summary.

Reported Decisions

Reported decisions state the determination and carry legal weight. The IRS can choose to accept these decisions (acquiesce) or not.

Memorandum Decisions

Memorandum decisions state the determination but don't carry legal weight. These decisions aren't published. The IRS can acquiesce or not.

Summary Decisions

Summary decisions apply to only one case and therefore carry very little weight. The IRS will not acquiesce because it is the opinion of only one judge. These decisions can be appealed to the District Court of Appeals.

Trial Court

- Taxpayer may challenge the IRS.

- Taxpayer must first pay the amount the IRS is claiming.

District Court

- Taxpayer requests refund and awaits IRS decision or 6 months (whichever comes first)

- Taxpayer files suit against IRS

- Taxpayer can request jury trial or be heard by single judge

- Courts follow decisions within its district

![]()

Tax Research Process

The tax research process involves working through the following steps:

- Determine facts and circumstances.

- Locate sources that address issue.

- Assess validity of sources.

- Update the file.

- Resolve the issue:

- Consider options and ramifications.

- Consider nontax concerns.

- Consider cost-effectiveness.

- Communicate the findings.

- Document all work in the permanent file.

Let's look at the tax research process in more detail in Video 1.2.

Part 1

PROFESSOR: Now we will look at the tax research process and how we present the evidence for a sound conclusion to the scenario being investigated.

How is tax research conducted and what does a tax professional need to focus on? The first step is to identify what you need to research. Make sure you have all relevant facts and you have asked all questions, and you understand the scenario at hand. You will then begin the research process itself. This is where you will identify law, regulations, revenue rulings, court cases that address the facts of the issue under investigation.

Once you have identified and collected authoritative sources, you will then start to create a solution, or solutions, and alternatives to the tax scenario. Then you will discuss the alternatives with the client, focusing on the following. What type of current and future ramifications are there? What non-tax ramifications could there be, as well as how much cost is involved to complete the scenario compared to the benefit actually realized?

After full discussion with the client on these aspects, an alternative would then be chosen. All information must be documented within a permanent file and must be communicated to the client in writing. The rest of this presentation will guide you through these steps.

The first place a tax preparer can start when searching a tax scenario is the IRS's site. Believe it or not, it is an easy site to navigate and is well maintained. You can search through the IRS publications and forms to help you get started in the right direction for your research. You never use this as evidence. It is only a starting point for a tax position to be determined.

Once you have more information about your tax issue, or if you wanted to bypass the IRS website, then you should use a professional tax library to conduct your research. You have access to different tax libraries. Remember, they have the same information, but they are organized differently. Let's look at a scenario and show you how to begin your tax research on that item.

Joseph is married, but his wife has left him and has had no contact with him. They don't have any children. Joseph comes to you for your help. He doesn't know how to file his tax return, since he cannot contact his wife. You are just a beginner tax student. You don't know what to tell him. What should you do?

You need to begin your research from the beginning. First, collect all facts and circumstances. During this process, you must ask questions. You will ask Joseph questions like, when did you get married? What is your wife's full name? What is her social security number? When is the last time your wife lived in your home? Has your wife contacted a lawyer? Are there any court decisions about your marriage, i.e. legal separation?

A preparer must make sure that they understand everything about the situation. They should ask questions like the ones listed. A preparer should never assume, but ask. Once you have the questions answered you can then proceed to the next step, research.

You can access the IRS website and use keywords to search for more information. As you can see, this search was conducted using keywords, [INAUDIBLE], married filing status. There are various sources that are then assessable. Once you start reading through these sources, it will provide guidance on the scenario at hand. Remember, this is not authoritative, so it is used only as a starting point.

Now, if you click on Publication 17, let's see what you get. It looks like Publication 17 is a great place to start. If you look, it provides information and guidance for marital status and filing status. You should then read through that material. This will help clarify that your keywords are good for your authoritative search, or to help you get more specific keywords for searching in the authoritative sources. Remember, it is the authoritative sources that are used for evidence in the tax position.

Professional tax libraries. Now that you are familiar with the available filing status, the scenario, and keywords for searching, you can now use the professional tax library to gather authoritative evidence. There are a few that most tax preparers and lawyers use to cite authoritative evidence for a tax position. Listed are a few. And what is even better is that you have access to them right now. All you need to do is click on the library links now. Let's use RIA Checkpoint for the demonstration, using Joseph's tax issue.

So we are now in RIA Checkpoint. On the left-hand side, please change the view using the dropdown box to Tax. Since you want to collect authoritative evidence, click on the Search tab at the top. You will then get the following.

Within the search area, select keywords to conduct your search and then what you want to search. Primary source material will give you results of the most authoritative evidence to support your scenario, so select those. Using the Keywords search box, enter Married Filing Status.

As you can see, the search results are categorized by type and authority. Internal Revenue Code with those key terms is listed first, then regulations, and finally, tax cases with the associated number of items to look at. Within the Internal Revenue Code search results, there is a result for Code Section 7703. Click on that reference to see if it will help. This is actual tax law, so let's see if there is any type of evidence here.

There is substantial evidence, it appears, for determining filing status when a person is married. Now you would continue to read through this section to see if there is evidence that provides help for Joseph's tax question. What filing status can he use for his tax return this year? You will see as you read through the evidence, it may lead you to more evidence, code section, or cause you to have more questions. That's why it is called research. You should be sure to collect all relevant information that is necessary to make a complete analysis and list of alternative actions.

It's a good time now to stop, take a breather, and remember a few key points. When conducting tax research, you must conduct research as necessary to find good evidence to help answer your tax questions. You must never make assumptions about the tax law or the scenario. Finally, read all evidence very carefully and make sure you understand what it is saying. This is very important so that you find the best action for your client.

When the research is finished, it is now time to determine alternative choices for the client. Based on Code Section 7703, Joseph is married at the end of the year if no court documents deemed him legally separated or divorced. Marital status is based on legal status on December 31st. He has one of two choices. He can file Married Filing Separately or Married Filing Jointly. We would then explain, based on research, how either would affect Joseph's current and future tax situation. And based on our client's input and discussion, take the best decided alternative.

Once the best alternative has been decided, it is now time to document all information in writing within a permanent client file, and also write a formal letter to our client on the tax issue, research, and resolution. We will now deal with that in our next presentation.

Part 2

An introduction must include the date, a list of all facts of the scenario at hand, the tax issue clearly stated, and a conclusion to the tax issue. If we look back at Joseph's tax issue from the prior presentation, you must be sure to include all facts, tax issues, and properly formed conclusions. This is necessary for the tax memo because it would be utilized if there is ever any question as to why a tax position was taken.

It is important that all the following occur with regards to the fact area. Be sure to clearly identify them. Provide a complete set of facts provided by the client. Pay attention and document all timing of events in proper order. And keep all facts together.

The complexity of the tax issue will determine how many issues must be addressed. Always keep all issues clearly stated. Write each one in the form of a question. Give details of the issue, but don't start using evidence at this point. And finally, arrange the issues in a logical sequence.

At this point, you will provide the conclusion of the issues identified in this tax scenario. You must be sure to include all issues and state the conclusion in a clear and unquestionable manner. This will prevent any uncertainty with the position taken.

The next step in your memo creation is to present all evidence collected. The best way to do this is to properly cite by code, identification numbers, and titles, as well as detailed information used to resolve the tax issue. You should always cite evidence from the most authoritative to least authoritative, as stated in the next lesson.

The final part of the tax research memo should include a brief statement on further information or recommendations. This is the typical process of writing a tax memo. Keeping it as a permanent record in a client's file is mandatory.

The final element of the tax research process is to communicate the information in writing to the client. You should date the letter, properly address, state all responsibilities of the parties involved, restate the facts of the tax issue, and then provide the recommendations and conclusions you agreed upon. A sample letter is in the next slide.

As you can see, the letter to the client is a normal letter style, where all items in the previous slide are addressed. Notice we don't bog down a client letter with code section and evidence. We present the scenarios and conclusions reached.

Finally, a review of the entire process is in order. Remember to carefully define and develop a clear understanding of the tax issue at hand. Research the issue, finding relevant evidence. Analyze the evidence.

And determine alternatives, paying special attention to tax and non-tax ramifications as well as cost benefit of each. Select the best alternative after discussion with your client. Communicate the issues and findings in a written letter to the client. And document all information in a tax research memo in a permanent client file.

Lesson Summary

This first lesson provided information on the birth and creation of the tax system currently used for federal income tax purposes in the United States. It discussed how tax law is actually created in the United States as well as the role of the IRS in tax administration. Remember, income tax isn't the only kind of tax. You learned about other taxes that exist in the United States, with a special focus on gift taxes. Finally, there was a detailed presentation on the tax research process, including how to use tax libraries and conduct tax research from start to finish. With this information as the starting point of this course, Lesson 2 will look at the tax structure and tax formula that is used as a basis for individual income tax calculations.

References

Eddlem, T. R. (2013). Before the income tax. Retrieved from https://www.thenewamerican.com/culture/history/item/14268-before-the-income-tax

Inheritance. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary (11th ed.). Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inheritance

Internal Revenue Service. (2016). Gift tax. Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/gift-tax

Internal Revenue Service. (2017). Instructions for Form 706. Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/instructions/i706

U.S. Const. amend. XVI.

U.S. Const. art. I, §§ 2–8.

Van Buren, A. (2015, July 13). Couple deep in tax hole need help in climbing out. Retrieved from http://www.uexpress.com/dearabby/2015/7/13/couple-deep-in-tax-hole-need