ACCTG410:

Lesson 1: Introduction, Background, and Review

Introduction | Video

Video 1.1. Course Introduction

Congress seems to have intended for a business’s taxable income to reflect the net increase in wealth from a business. The result is that, according to IRC §162, businesses can deduct expenses incurred to generate business income. This is a relatively broad and ambiguous section of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), which Congress and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) supplement with specific statutory and regulatory rules authorizing deductions. The rules generally apply to all types of business entities, including sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies (LLCs), S corporations, and C corporations.

In this lesson, you will review the general rules for business expenses, as well as the types of expenditures that are not deductible. You will also jump into some specific tax issues with income and expenses.

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to

- describe the requirements and limitations on business tax deductions,

- explain the permitted tax years,

- describe the permitted tax accounting methods and the effect on timing of recognition of income and expenses, and

- identify specifically permitted business tax deductions.

Lesson 1 Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

Reference

Trade or Business Expenses, 26 U.S.C. § 162 (2011).

Authorization to Deduct Business Expenses | Video

Video 1.2. Chapter 1 Overview

You may recall from ACCTG 310 that the income is to be applied to “all income from whatever source derived” (U.S. Constitution, 16th Amendment and IRC §61(a)). A strict interpretation of this wording lead to the conclusion that all income was to be taxed and no expenses deducted. Fortunately, Congress thought better of that interpretation and created IRC §162, which grants authorization to deduct business expenses.

Specifically, §162 states:

There shall be allowed as a deduction all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business . . .

This is a relatively broad and ambiguous authorization to deduct business expenses. This ambiguity has led to many regulations and court decisions. In an effort to clarify some of the ambiguity, the courts have ruled that there are three criteria that must be satisfied for a business expense to be deductible. It must be ordinary, necessary, and reasonable. Click below to learn more about ordinary, necessary, and reasonable business deductions and to see examples.

Ordinary

To qualify as ordinary, an expense must be appropriate for the business under the circumstances. Some might call this the reasonable person criteria. That is, would a reasonable person in this business under these circumstances have incurred this expense? The courts have also asked whether other businesses in this industry normally incur the expense. That means an ordinary expense can vary across industries and even between businesses in the same industry, if they use different business models.

Necessary

A necessary expense is one that is conducive to the business activity. However, the courts have noted that a necessary expense does not have to be essential to the business, only helpful in running the business. Again, necessary expenses can vary across industries and between businesses in the same industry.

Reasonable

The reasonable criterion refers to the amount of the expense. An expense is deductible only to the extent the amount is reasonable.

Limitations on Deducting Business Expenses

In addition to having to satisfy the requirement to be ordinary, necessary, and reasonable, business expenses will not be deductible for taxes if they are contrary to public policy. Capital expenditures, expenses associated with earning tax-exempt income, personal expenditures, or another person’s or entity’s expense are also not deductible for tax purposes. Click on each button below to learn more about these limitations.

Accounting Periods, A.K.A. Tax Years

There are three types of tax years allowed by law. These are calendar year, fiscal year, or 52/53 week year. There are also, in special situations, short tax years. Click on each button below to learn more about these accounting periods.

Accounting Methods

Keep in mind that the accounting methods you learned in financial accounting (a.k.a., generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)) are created by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Congress and the IRS create the tax rules. Those differing sources mean the rules can legitimately differ. Generally, GAAP encourages businesses to choose permissible accounting methods that accelerate income and defer deductions. For taxes, which require a cash outlay, businesses’ incentives are to defer income and accelerate deductions. Be careful that you don’t impose the financial accounting rules when you’re working in the tax area.

A taxpayer’s accounting method determines the year in which an item of income or a deduction is reported on the business’s tax return. The two options are the cash method or the accrual method. Click below to learn more about these accounting methods.

Cash Method

Under the cash method, businesses report income when it is received or made available to the taxpayer and deduct expenses when those expenses are paid. If a cash-method business operating on a calendar year sends a bill to a client on December 20 and receives payment on January 15, the business would report the revenue on the tax return in the later year, when it received the revenue. Similarly, if a cash-method business operating on a calendar year receives a bill from a vendor on December 20 and sends payment on January 15, it would report the expense on its tax return for the later year, when it was paid.

One exception for all cash method businesses is if they have substantial inventories. In that case, the inventories must be accounted for using the accrual method.

Accrual Method

Under the accrual method, the business reports income when it earns it and deducts expenses when they are incurred. The receipt or spending of cash may be irrelevant to the timing of income and expense recognition. An accrual method business will record income when it has satisfied the all-events test. The business will record expenses when it has satisfied both the all-events test and the economic performance test.

All-Events Test

The all-events test for income requires recording of income when

- all events have occurred that determine the business’s right to receive the income, and

- the amount of income can be determined with reasonable accuracy.

If a business signs a contract with a customer, the business is not obligated to record that income for taxes, since the business has not yet fulfilled its obligations under the contract. Only when the contract terms have been satisfied has a business using the accrual method satisfied the all-events test. However, if an advance payment is received at the contract signing, the taxpayer has the option of recording the income for taxes at the time of receipt, or they can defer recording it for taxes until the income is earned by fulfilling the contract.

The all-events test for expenses allows the deduction of an expense when

- all events have occurred that determine the business’s obligation to pay the expense, and

- the amount owed can be reasonably determined.

As in the previous paragraph, the companies may fulfill this test and create an obligation when a building or drug development is partially completed and the obligation to pay has been created.

Economic Performance Test

Businesses fulfill the economic performance test for expenses when services or goods are actually provided to the taxpayer. Whatever needed to happen for the transaction to be complete has happened. For example, when the pharmaceutical company delivers the drug under development, or the construction company completes the building, and the taxpayer takes delivery on a good or service. The obligation for the taxpayer to pay now exists, so the test is fulfilled.

Mixed-Use Assets or Expenses

The rules determining deductible business expenses get murky when there are mixed-use assets or mixed-use expenses. These are assets or expenses that are used for both personal and business purposes.

For example, if the business operates out of an office in the owner’s home, the home is a mixed-use asset. The expense of heating and air conditioning in that home would be a mixed-use expense. In these cases, the cost of the asset or expense must be allocated between business and personal use. So, if the office uses 20% of the home, 20% of the expenses of running that home are deductible business expenses, and the owner can capitalize and deduct 20% of the cost of acquiring and improving the home as depreciation.

Click each button below to learn more about mixed-use assets and expenses.

Specific Business Deductions

Businesses incur expenses in order to generate revenues, which determine the success or failure of the business. Some are straightforward, while others have twists or "quirks" that may be confusing, so you want to discuss those expenses. There are also losses, which are business deductions beyond the control of the business. Let’s start with an easy expense, or is it?

Click below to learn more about specific business deductions.

Meals and Entertainment Expense Deduction

Businesses will pay for meals and entertainment of employees to help team building, or of customers to help generate business. So, there is a real business purpose to this expense. However, only 50% of business meals and entertainment were previously deductible. However, under the new tax law, most business entertainment expenses incurred subsequent to December 31, 2017 will be considered 100% nondeductible, with the exception of expenses incurred for the benefit of the taxpayer’s employees (e.g. office holiday parties), which remain 100% deductible.

Below are examples specified by the IRS of non-deductible entertainment expense under the TCJA: Night clubs, Theaters, Country clubs, Golf and athletic clubs, Sporting events, Hunting/fishing and similar trips, including such activity relating solely to the taxpayer or the taxpayer’s family.

While several types of entertainment will no longer be deductible, a number of activities will not be affected by the code. As of now, if an employee is working overtime and the employer provides dinner money, that expense will be allowed to be deducted. If a hotel is maintained by an employer while an employee is staying there for business travel, there will not be any limits for the deduction.

Also, business meals occasionally provided to employees and for the convenience of employers are no longer fully deductible and subject to the 50% deductibility limitation under §274 for tax years 2018-2025. After 2025, such business meals will be treated as non-deductible. Several requirements are in order to claim a business meal deduction. The meal must have happened during the taxable year for trade or business and cannot be extravagant for the event. The taxpayer or employee of the taxpayer has to be present. If the taxpayer only gives money to a client but is not actually there, that money will not count towards the deduction. The client must either be a current client or a potential client – a previous client that the taxpayer remained friends with will not be allowed.

Domestic Production Activities Deduction (DPAD)

Congress created the domestic production activities deduction (DPAD) in an effort to encourage manufacturing plants to locate in the United States. Basically, it’s a subsidy for the cost of producing goods, some construction services, filmmaking, and other specified industries in the United States.

It’s a complex calculation, but the essence is that businesses must allocate revenue and expenses between qualifying activities, which are certain production activities that take place in the United States, and nonqualifying activities, such as foreign production activities and other production activities in the United States.

The deduction is 9% of qualified production activity income (QPAI), but is limited to the business’s overall income, and to 50% of wages associated with the production activity. Congress imposed the limitation based on wages to encourage hiring employees to raise the limit and, in turn, the deduction. QPAI is the business’s net income (revenues minus cost of goods sold minus manufacturing expenses) from the qualifying U.S. production activity.

Business Casualty Loss Deduction

Business casualty losses are the result of events beyond the control of the business in which assets are stolen, damaged, or destroyed. The tax effects are handled differently from personal casualty losses, so be careful not to confuse them.

The calculation of a business casualty loss deduction depends on whether the asset is completely destroyed or stolen, or if it’s only partially destroyed. If the asset is damaged but not destroyed or stolen, the amount of the deduction starts with any insurance proceeds received due to the loss. From those proceeds, subtract the lesser of a) the asset’s tax basis, or b) the decline in value of the asset as a result of the casualty. This is the deductible casualty loss when the asset is damaged but not destroyed.

If the asset is destroyed or stolen, the deductible amount is the insurance proceeds, minus the adjusted tax basis of the asset. As a reminder, adjusted basis is the cost of the asset minus total depreciation taken over the life of the asset. Other adjustments are possible, but that is the basic calculation of adjusted basis.

Inventory

Inventory is included in the deduction section because of its relationship to cost of goods sold (COGS), often the largest single business deduction. A business that has substantial inventories must use the accrual method to account for inventory and gross profit, even if the business uses the cash method to account for the rest of its business.

Congress created an exception for businesses that do not sell substantial amounts of goods. This exception allows a cash-method business to use the cash method to calculate inventories and gross profit, if annual gross receipts average no more than $10 million per year for the 3 prior years. So, if a business has gross receipts for the previous 3 years of $8 million, $10 million, and $11 million, the average annual gross receipts are $9.67 million, meaning the business can choose whether to use the cash method or the accrual method to calculate inventory and gross profit.

Congress also created the uniform cost capitalization rules (UNICAP) in an attempt to bring uniformity to the tax calculation of inventory and COGS. The UNICAP rules also delayed the deduction of some costs, raising tax revenues for the government. The UNICAP rules require that costs incurred (inside a production facility, as well as costs incurred outside a production facility in support of production activities) must be capitalized into the valuation of inventory. The deduction of these costs will be delayed until the product is sold. There are exceptions for selling, advertising, and research costs, and for businesses that resell personal property (personalty) and have no more than $10 million in average annual gross receipts for the prior 3 years.

Businesses also must choose an inventory cost flow assumption to calculate the value of inventory and COGS. Please be aware that the choice of cost flow assumption does not have to match the actual physical flow of goods. For example, you may be aware that grocery stores are always rotating their stock to increase the chances of selling older items. That is, older items are moved to the front, and newer items are put toward the back. Since most people pick up the item closest to them, the physical flow of goods is first-in, first-out (FIFO). However, the grocery store can pick another method to account for inventory for tax purposes.

Generally, businesses will choose from first-in, first-out (FIFO), last-in, first-out (LIFO), or specific identification.

- Under the FIFO system, the cost flow assumption is that businesses sell the older items first, leaving newer items in inventory. If costs are rising over time, this assumes, relative to other methods, that lower-cost items are in COGS, and higher-cost items are in inventory.

- Under the LIFO system, the cost flow assumption is that businesses sell newer items first, and older items remain in inventory. This cost flow assumption gives the opposite result from FIFO when costs are rising, since it acts as if the newer, higher-cost items are sold first, putting higher costs into COGS and reducing taxable income. Because of this artificial reduction in taxable income, the tax law now mandates that LIFO can be used for tax purposes, only if it is also used for financial reporting purposes.

- The final option is specific identification, which assumes a business can identify the specific cost of each item sold. At one time, this was a very difficult assumption if the business sold mass-produced items, making it a useful tool only in businesses that produced or sold custom-made products. However, the development of more advanced computer and scanning technologies has made the specific identification cost flow assumption a more realistic possibility than ever before.

Using the IRAC Method and Bluebooking in Memos and Discussions

Please review and learn about the IRAC method and Bluebooking for use in both your online discussions and your memos. Where applicable, student need to substantiate their thoughts or opinions in the online discussions in lieu of just a general opinion or thought without something to substantiate it. Below you will find references and sites that illustrate how to accomplish these two objectives.

IRAC Method

The IRAC method is the standard in the business world as far as discussions in memorandums and should be used as a basis for your online discussion. The following resources provide details on this method.

How to Brief a Case Using the "IRAC" Method

Video 1.3. Introduction to IRAC

Video 1.4. How to IRAC a law case

Bluebooking

Bluebooking is the preferred method citing for memorandums and should also be used as a basis for your online discussions. Also see the Georgetown Law Library Bluebook Guide on the next page.

Video 1.5. Bluebooking Series Part I An Introduction to the Basics.

Video 1.6. Bluebook Lesson 1 - 19th Edition.

Accessing the University Libraries

You can access University Libraries resources either directly from the accounting guide page in your course or from the Penn State Libraries website.

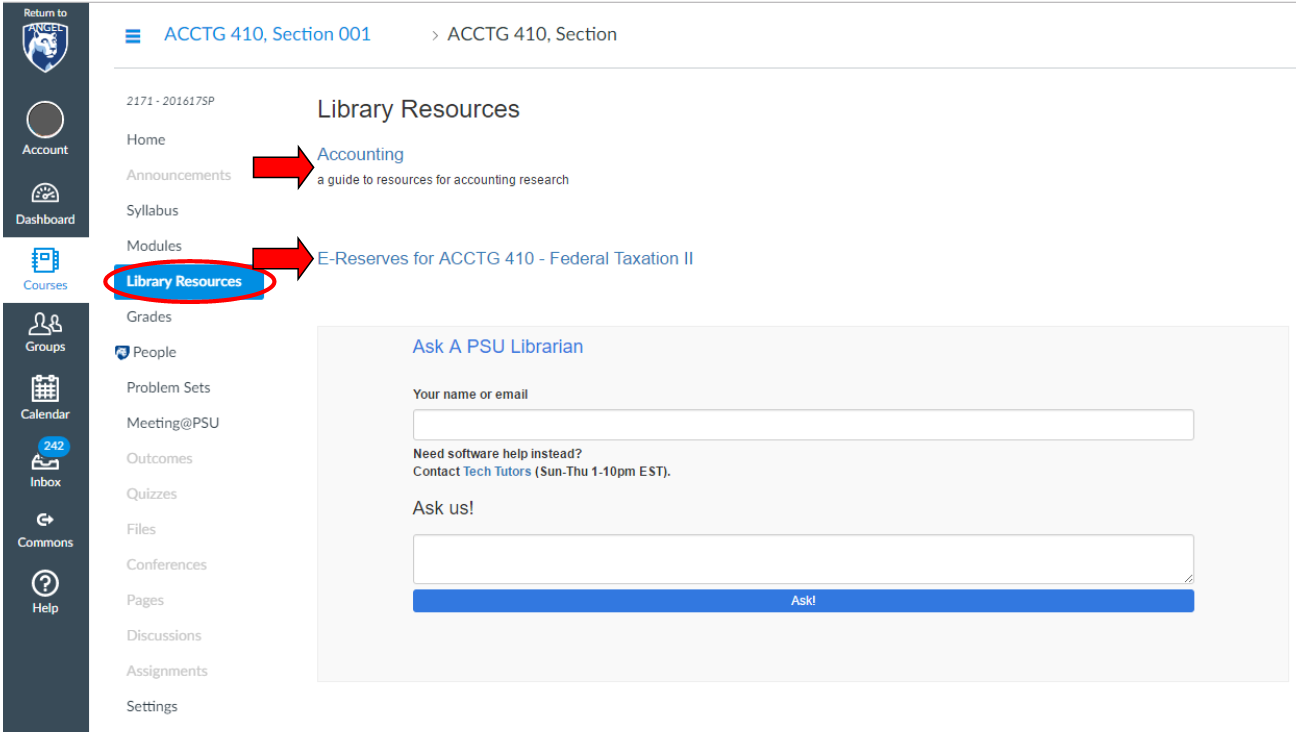

Accessing the Accounting Guide through Library Resources in Course Navigation

The easiest option is to access the accounting guide through Library Resources in the Canvas course navigation as the links in the accounting guide will bring you directly into specific resources.

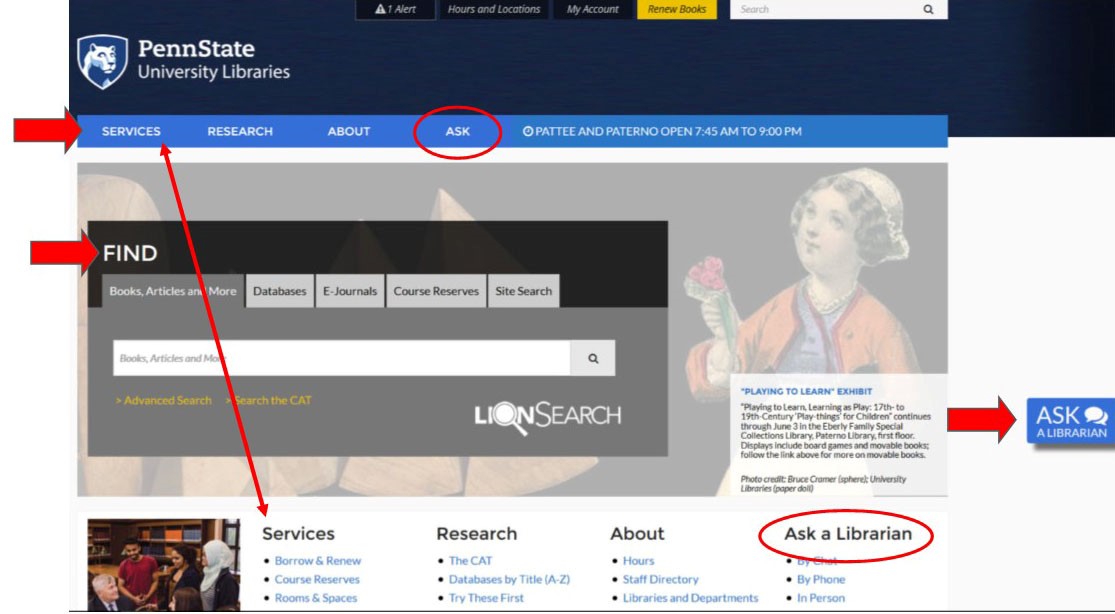

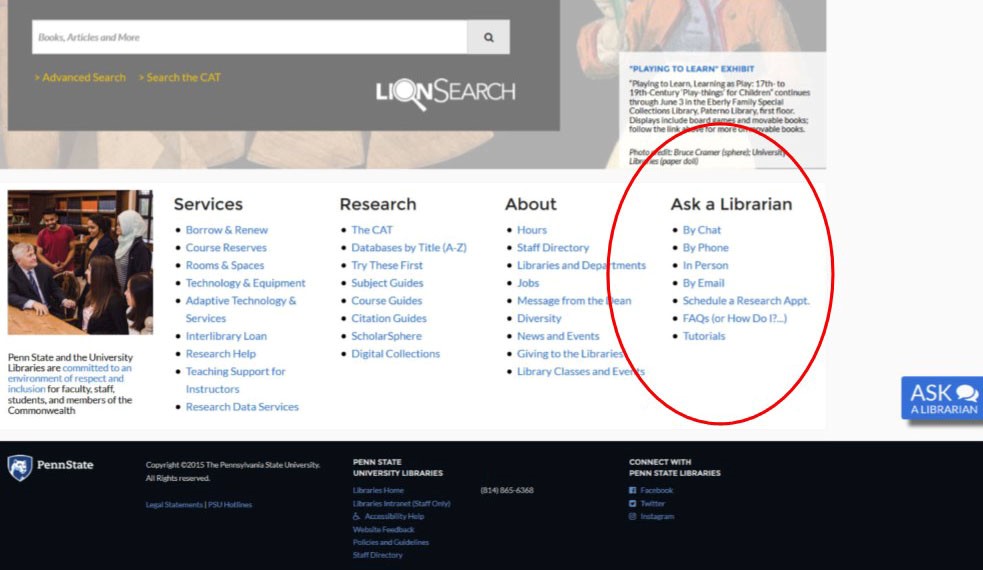

Accessing Library Resources through the Penn State Libraries Website

You can also access these resources via the Penn State Libraries website. Once you have navigated to the Libraries main page, you will notice the following links near the top of the page: Services, Research, About, and Ask (see Figure 14.3). If you click on each of these headings, you will find a drop-down menu of additional selections. The same options are provided under similar headings toward the bottom of the home page. There may be some resources that are restricted, such as paid databases or journals, so you may need to log in with your Penn State WebAccess user ID and password to access to these items. Next, let’s look at the Find box in the center of the page.

Find (aka LionSearch)

The Find heading allows you to search the library resources (see Figure 14.3):

- Books, Articles and More searches the general catalog and searches almost all items in the library.

- Databases searches within the databases to which the school has subscriptions.

- E-Journals allows you to search journals that Penn State has access to in electronic format.

- Course Reserves is where you will go to access any materials that have been placed on reserve for your use as part of a course. These are often reference materials or portions of textbooks. You may search in this tab by course number, course name, instructor name, or name of resource on reserve.

- Site Search will search the library web pages.

Help for any of these resources is available by clicking on either the Ask a Librarian button (see Figure 14.3) or one of the links under the Ask a Librarian heading (see Figure 14.4).

Ask or Ask a Librarian

Ask gives you the option of e-mailing, starting a chat with, or phoning a librarian for help. The Ask a Librarian heading found at the bottom of the page has a list of options below it (see Figure 14.4), which mostly list different means of contacting a librarian for assistance. The last two, FAQs and Tutorials, are guides to the library resources. FAQs (or How Do I?...) is just what it sounds like: answers to the most frequently asked questions.

By following the Tutorials link, you will find many recorded tutorials about the library and services. However, I recommend that you view the library guides that are linked through the Penn State Online/World Campus libraries page.

Evaluating Information

As part of this lesson, you should watch all six of the videos under Evaluating Information. You should also read the associated information on each page. The videos are short (less than 2 minutes each) and include

- evaluating sources,

- evaluating authorship,

- evaluating content,

- evaluating currency,

- evaluating citations, and

- publisher.

You may also want to view the short LionSearch Tutorial videos, if you need further assistance.

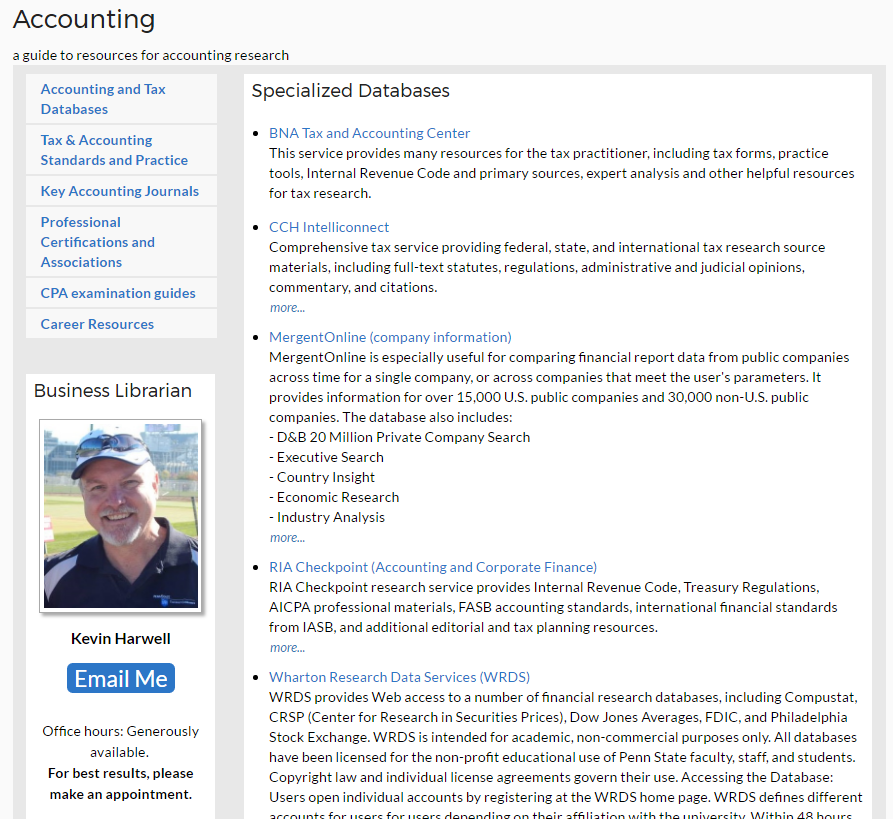

Databases you may want to consider...

- Bloomberg Bureau of National Affairs (BNA) is a leading source of legal, tax, regulatory, and business information (Wikipedia, n.d.). The database includes authoritative coverage for taxes, accounting, labor and employment, intellectual property, banking and securities, employee benefits, health care, privacy and data security, human resources, the environment, and health and safety. You have access to the Bloomberg BNA through the Penn State Libraries.

- Commerce Clearing House (CCH) is a Wolders Klewer business database that tracks, reports, explains, and analyzes tax and related law in over 700 publications in print and electronic form for tax, accounting, legal, human resources, banking, securities, insurance, government and health care professionals. (Wolters Kluwer, n.d.). You have access to the Business and Finance Internet Research NetWork, Health and Human Resources Research Network, and Intelliconnect through the Penn State Libraries.

- LexisNexis Academic provides access to full-text documents from over 17,000 credible sources of information and pinpoints relevant information for a wide range of academic research projects. (LexisNexis, n.d.). You have access to LexisNexis Academic, including News Sources and State Capital, through the Penn State Libraries.

- Research Institute of America (RIA) Checkpoint is a Thomson Reuters database that includes RIA International, Federal, State and Local Tax Libraries, along with Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Codification and Governmental Accounting Research Systems. (SNHU, n.d.) You have access to both Tax and Estate Planning and Accounting and Corporate Finance through the Penn State Libraries.

Introduction to Research

In this lesson, you will complete a research project. Penn State has one of the top-10 research libraries in the United States (Penn State News, 2015). This fantastic resource is available to you as a student of the World Campus. One of the goals of the research assignment is to help you to become familiar with some of the available resources.

Library Resources

In your project, you are asked to write a tax memo where you will need to do research, arrive at a solution, and communicate tax research to a client. The course reserve for this lesson, Understanding and working with the federal tax law, outlines a five-part process to follow in writing a tax memo, consisting of

- identifying the problem,

- locating the appropriate tax law sources,

- assessing the validity of tax law sources,

- arriving at the solution or at alternative solutions, and

- communicating tax research.

You can access this reading via Library Resources in course navigation (see Figure 14.1).

Accounting Guide

The accounting guide (Figure 14.2) is a Penn State Libraries resource specifically geared to the types of research and specialized databases you may encounter as an accounting professional. Through this page, you have access to the Penn State business librarian who can help you with these resources, if needed, and you can access specialized databases and materials for this assignment. The accounting guide may also be accessed through the Penn State Libraries home page or through Library Resources in course navigation by selecting Accounting - a guide to resources for accounting research (see Figure 14.1).

Summary

This lesson presented the concepts and requirements underlying tax deductions for businesses, including the legislative justification for deducting business expenses. You also reviewed the requirements for a business expense to be a tax deduction and the types of business expenses that cannot be deducted. You then discussed the permissible tax years and tax accounting methods. Finally, you discussed mixed-use assets and expenses, and ended with introductions to some specific business tax deductions.