BA421:

Lesson 1: Introduction to Project Management

Introduction

Many managers must plan and manage projects. You may be in production, trying to determine a better way to cut costs in the plant. You may be in marketing, charged with laying out a marketing plan for new products. You may have to audit account books in one office of your company, in order to improve efficiency.

All of these projects, and many others in your organization, involve deadlines, particular results, budgets, and ambiguity. They require coordination among numerous people, and they require innovation to solve problems. Indeed, projects are the “life blood” of innovation, and today’s project managers must create innovation in order to compete in a changing world. All project managers can do a better job of getting innovative projects done on time, within budget, and according to desired quality standards.

Adapted from "What Every Manager Needs to Know about Project Management", ©Summer 1988 by W. Alan Randolph and Barry Z. Posner

Learning Objectives

When you have successfully completed this module, you should be able to do the following:

-

Define project and project management.

-

Explain the differences between projects and processes/operations.

-

Identify the basic parameters for managing trade-offs.

-

Describe the project life cycle, list its phases, and discuss how it relates to project expenditures.

Lesson Readings & Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

What Is a Project?

Most, if not all, of us have managed and executed projects of some kind, knowingly or unknowingly. For instance, organizing a birthday party, a wedding, or a vacation, or building or modifying your own home are all examples of a project. In short, all of us have managed a project—successfully or unsuccessfully.

Characteristics of Projects

All of the projects listed above have the following common characteristics:

-

Definite start and end dates: We don't start working on a birthday party project a year in advance. Usually, we start working a few weeks ahead of time, with the end date being the day of the party.

-

A well-defined objective: The objective could be a fun-filled party, a vacation, or some other event.

-

A series of independent tasks or activities: For example, to order wedding invitation cards, you must first determine the guest list; to place an order for catering, you must know in advance how many guests will actually turn up for the wedding party; and so on.

-

A unique or one-time event: Birthday parties don't happen every day, every week, or even every month.

-

Assigned responsibilities: This may involve a single individual or group of people working together, but all will have clearly defined responsibilities.

-

A plan and a budget: After all, few of us can afford to throw a million dollar party or enjoy a vacation in the Bahamas.

-

Many stakeholders: A wedding may have several stakeholders, such as the various suppliers (decorators, a caterer, hall provider, transportation provider, etc.), relatives and friends, and of course, the couple themselves.

-

Some degree of uncertainty: For instance, you may have to cancel the party or vacation due to inclement weather, illness, or some other reason.

Therefore, a project is a temporary activity with a definite starting date, specific goals and conditions, defined responsibilities, a budget, a plan, a fixed end date, and multiple parties involved.

Examples of Projects

The following projects are larger in scale than a birthday party or vacation, yet they also have the characteristics of projects listed above:

-

Think about the United States presidential election. Each candidate engaged in a project to meet one goal: to be elected president. There was a deadline (election day), a budget (fundraised), resources to be managed on their committees, and numerous stakeholders (the electorate, the candidates’ individual parties, their families, the media).

-

Penn State engages in hundreds of research projects every year, on a wide variety of topics. Each project has a budget, resources, scope, and schedule that need to be managed. Projects in the news at Penn State can be found here: Penn State Research.

What Is a Project Manager?

To manage a project, you need a team of committed people. You also need a person who will lead the group, providing direction and motivation for others. The role of the leader and their team is to plan all the activities pertaining to the project, ensure the successful execution of each activity within the estimated time and budgets, monitor and control any time or budget overruns, and take timely action to fix any problems. The leader will ensure that the project objectives are achieved smoothly through trade-offs among the scope, quality, cost, and schedule (more on this later).

In the context of a project, the leader is known as the project manager (PM).

Projects Versus Processes: What Makes Projects Different?

Having defined projects, let's consider how they differ from processes, such as operations or programs.

Projects Versus Operations

Every day you commute from home to your office. This is a routine decision made on a regular basis and can therefore be called an operation. Similarly, take the case of an automobile-manufacturing plant. Suppose this plant manufactures cars every day; this work can be termed operations. However, if instead of driving to work you drive to a vacation spot, or if the automobile manufacturer installs a new production line to manufacture more cars annually, these activities would be projects.

How do you know if something is a project or operation? Consider Pinto's (2016) list of elements of a project:

- Complex, one-time processes

- Limited by budget, schedule, and resources

- Developed to resolve a clear goal or set of goals

- Customer-focused

The vacation and new production line examples have the characteristics of projects: defined start and end dates, deliverables/goals, limits on resources, and so on.

Thus, projects differ from day-to-day operations, and that’s what makes them special. There are companies in the business of managing projects, but many people work on projects in addition to their day-to-day activities as they drive change through their organization.

Projects Versus Programs

Now consider the difference between a project and a program. Suppose you're pursuing your BSB degree at Penn State. This process can be called a program. However, in this program you will be executing many smaller projects (i.e., taking courses), which are essential for the completion of this program. You can play around with the projects (i.e., take courses that suit your schedule, adjust for major/minor requirements, etc.). What makes these courses projects is that selecting them is not a routine, day-to-day decision, and they all have distinct start and end dates and key deliverables (e.g., assignments).

Understanding programs is important, as decisions you make for individual projects also impact your programs—or project portfolio. More on that later.

References

Pinto, J.K. (2015). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. (4th ed.) Prentice Hall, p. 5-6.

Constraints to Project Success

The Triple Constraint

Perhaps you've heard the saying, “Good, fast, cheap: Pick two.” This sentence illustrates the idea of constraints: Choosing certain options limits others.

The triple constraint refers to a set of potentially competing project priorities, the most commonly recognized being scope, cost, and schedule. Simply put and as shown in Figure 1.1, we can think of this as what needs to be done (performance), how much the project is going to be (budget), and when it is going to be completed (time).

This concept is defined in the maxim “good, fast, cheap: pick two.” When managers are making decisions and managing trade-offs in projects, they often have to sacrifice one aspect of the triple constraint in order to have another aspect. For example, think about a time when you were approaching the date for submission of a term paper to your professor. As you get closer and closer to the deadline, the “nice to have” aspects of your assignment get cut, and you focus on the “need to haves,” or you may not proofread your document as carefully as usual since you are short on time. Sacrificing quality to meet the deadline and minimum requirements is an example of how the triple constraint works.

The Quadruple Constraint

As project management concepts were formalized, it was realized that the true success of a project couldn't be defined through the triple constraint of cost, scope, and schedule alone. Companies developed products that were readily available to consumers but unsuccessful in the market. Why were they unsuccessful? They didn't satisfy their customers' needs, and therefore customers did not purchase (i.e., accept) the product (Pinto, 2016). Why might customers not accept the results of a project?

-

It doesn’t meet their needs (i.e., provide what they want).

-

It doesn’t meet the standard of quality they desired.

Due to the realization that customer satisfaction is as important as the other three components, the triple constraint evolved into the quadruple constraint. The quadruple constraint adds a fourth criterion, client acceptance, to the model to reflect the importance of evaluating the client's needs in addition to the three traditional success criteria. Managing cost, scope, and schedule will get a project to the finish line, but if the customer does not buy-in (known as client acceptance), is it truly successful?

The article “From Google Glass to iPhone 4, Five Biggest Tech Blunders” describes several products that had issues in the market due to a lack of client acceptance, including the HD-DVD and the Microsoft Zune (Bajaj, 2016). The lack of client acceptance can be attributed to several factors in either case, but the products that gained the market share (Blu-Ray outsold HD-DVD, and sales of Apple’s iPod far outpaced the Zune) did so due to overwhelming customer acceptance.

Can you think of any other products that met the “triple constraint” but were unsuccessful in the market?

References

Bajaj, K. (2016, September 22). From Google Glass to iPhone 4, five biggest tech blunders. The Economic Times (Online). Retrieved from http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/from-google-glass-to-iphone-4-five-biggest-tech-blunders/articleshow/54459595.cms

Pinto, J. (2016). Project management: Achieving competitive advantage (pp. 16-17). New York, NY: Pearson.

The Project Life Cycle

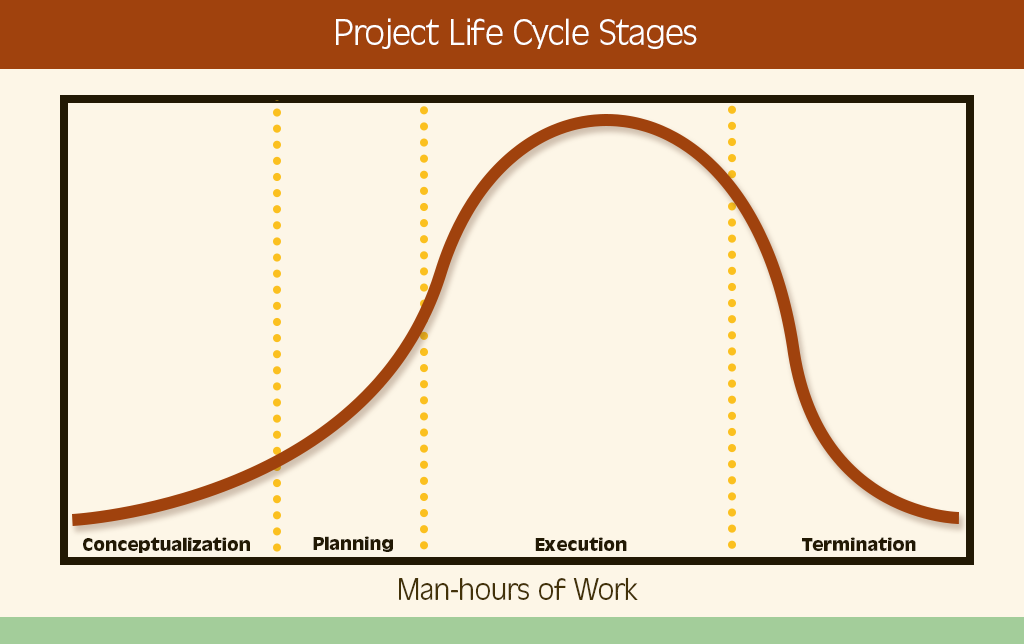

All products have a life cycle, and so do all projects.Briefly, a project life cycle (visualized in Figure 1.3) consists of four phases: Conceptualization (sometimes called Initiation/Startup), Planning (Development), Execution, and Termination (Closeout/Finish).

The tabs below provide the details of the project life cycle, which includes the activities performed during each phase of the project. Most of the activities listed will be discussed in detail throughout this course.

Initiation

During the conceptualization phase, the project manager works wit hteh project sponsor to further define and document the key project requirements. During this phase, we think through the parameters of the quadruple constraint, then create estimates for what (and who) is needed to complete the project. This is documented in the project charter, including approvals from the key decision-makers."

Activities During the Initiation Phase

The following activities should occur during the initiation phase:

-

Gather data

-

Analyze needs and risks

-

Set goals and objectives

-

Get approvals

-

Formulate business case

-

Determine strategic fit

-

Draft scope and schedule

-

Create project charter

-

Estimate budget

Planning and Development

Project planning builds on the work done in project initiation, refining and augmenting the key project parameters and project plan deliverables. Usually, additional members join the project team, and they assist the project manager in further elaborating the details and requirements of the effort.

Activities During the Planning Phase

During the planning phase, the following activities should occur:

-

Establish baseline schedule and budget

-

Perform risk analysis

-

Obtain go/no-go and approvals from decision makers

-

Build project team

-

Plan deliverables

-

Define project quality parameters

-

Finalize scope

-

Communicate with customers and stakeholders

Execution

Project execution and control is where most of the resources are applied/expended on the project. This phase usually starts with a kickoff meeting (a meeting of various stakeholders of the project), which marks the official beginning of the project. The early stages of this phase will see a significant increase in the number of team members. It is the job of the project manager to enable the project team to execute the tasks of the project on time and within budget.

Activities During the Execution Phase

The following activities occur during the execution phase:

-

Hold kickoff meeting

-

Motivate project team

-

Forecast project expenditures and delivery date

-

Resolve issues and conflicts

-

Provide key deliverables

-

Monitor and control

-

Evaluate quality, time, cost, and risk management

-

Change scope (if necessary)

-

Control progress report

-

Communicate with customers and stakeholders

Closeout and Finish

Project closeout involves assessing the project outcome as well as the project team's performance. Effective assessment requires gaining feedback from customers, project team members, consumers, and other stakeholders. Many times, a formal project critique (or post-mortem) is organized by the project implementation team. A project critique critically analyzes the shortcomings of the project execution, how these shortcomings could have been overcome, lessons learned, and so on. Usually, all the direct stakeholders of the project are involved in the project critique.

Activities During the Exit Phase

Following are activities that occur during the exit phase:

-

Finalize project

-

Train customers

-

Reassign project team to new activities or projects

-

Report to customer

-

Contract closeout

-

Solicit team feedback

-

Document lessons learned

-

Perform project critique

-

Archive documents

So, why do project managers care about the project life cycle? Understanding the life cycle and the costs associated with each phase helps predict the amount of effort required during each phase of the project. By utilizing this information, project managers can then predict the budgetary requirements of each phase and manage cash flow.

References

Pataki, G. E., Dillon, J. T., & McCormack, M. (2003). The New York project management guidebook (Release 2) [Electronic version]. New York: New York State Officer for Technology.

Job Prospects for Project Managers

You may have wondered at some point, Why does Penn State want Business majors to take a 400-level course in project management? A lot of the topics discussed throughout the semester will seem rather technical. But Penn State wants you to have these skills, as they will make you more competitive and successful in the job market. Here’s why:

-

Project management is experiencing rapid growth. Recruiter.com reports that in the past five years, jobs in project management appear to have grown about 30% (Larsen, 2011).

-

Projects are the building blocks in the design and execution of organizational strategies. In the textbook readings for this lesson, we learn that projects are how we achieve our company’s goals. We use projects to drive change and therefore promote success in our organizations. Good managers look for ways to make things better within an organization, and we can accomplish this through projects.

-

You can find a career in project management in almost any industry. It has been reported that “many of today’s hot jobs—and the projections for the next 10 years—give an edge to workers who can bring innovations to market, the trademark of a top project manager” ("Job Market Improves for Project Managers," 2013).

How do project managers receive training and learn more about best practices? Project managers around the world have united to form the Project Management Institute. This organization has over 450,000 global members and over 280 local chapters internationally. PMI offers the internationally recognized Project Management Professional (PMP) certification, which can be earned by experienced project managers to improve their job prospects and ability to deliver projects successfully.

PMI also publishes the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBoK). This is a valuable tool for all project managers and will be referenced throughout this course.

References

Job market improves for project managers. (2013, May 13). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/docview/1350142842?accountid=13158

Larsen, M. (2011, May 13). Five trends in project management jobs. Recruiter.com. Retrieved from https://www.recruiter.com/i/project-management-jobs/

The Integrated Project and Microsoft Project

Chapter 1 of Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage goes into great detail about why projects are important. You learned that job prospects for project managers are growing, and even if you don’t want to become a project manager as a profession, having project management skills will help you to get ahead in your career. In this course, we are going to provide you with several hands-on activities to show you how to apply the concepts that you learn in this course:

-

Project Management Software: As a part of this course, you will be required to complete training in the use of project management software (as part of Lesson 11). You will learn basic skills of project management software. If you use a Windows-based operating system, you will learn Microsoft Project. If you use Mac-based system, you will learn ProjectLibre.

-

The Integrated Project: You will apply the concepts learned in this course directly by completing the Integrated Project. The Integrated Project requires small teams to complete a project scope statement document for a hypothetical project, the topic of which will be selected by the team. This document will be submitted for grading throughout the semester. The Integrated Project will be kicked off in Lesson 3.

Lesson Summary

In this lesson, we discussed the definition of a project, the project life cycle, and the basic techniques for managing tradeoffs in projects. Learning techniques of project management is important for Business majors; they will give you additional tools to be more marketable and productive in the workplace. By completing the Integrated Project, you will be able to directly apply the concepts you're learning throughout the semester.