BA462:

Lesson 1: Overview

Lesson 1 Introduction

"Business strategy is the planned and realized set of actions a firm takes to achieve its goals" (Rothaermel, 2014). Business strategy, as a subject, includes the decisions that management teams make in order to guide their way through the competitive landscape. As opposed to other subjects that you are studying (such as accounting, marketing, human resources, or finance), business strategy views the firm as a unit and addresses how this firm must act and react in order to survive from one time period to another. Much of what strategists analyze, therefore, is external to the firm.

Another way to define business strategy is as the study of competition. This course will focus, to a large degree, on how firms make decisions in order to outcompete rivals. Therefore, we can state that the main goals derived from an effective business strategy are that the corporation survives and that it thrives. But how do managers makes such decisions? It is not an easy task to be able to make important decisions in the face of incomplete and noisy information. In this lesson, we will study the types of issues, market actors, and events that managers must be cognizant of in order to effectively formulate and implement firm strategy.

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to

- define the nature of interorganizational competition,

- visualize competition as a chess match,

- define managerial decision-making constraints, and

- consider the effects of external actors and external events (shocks) on a competitive landscape.

Lesson 1 Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

Strategic Decision-Making: Competitive Environment

You could think of business strategy as a chess game. In chess, before you make a move, you model the most likely subsequent move of your opponent and then, conditional on what he or she will do, you finalize your move. A poor way to play chess is to make moves and not consider what your rival will do next since you will be put in checkmate very quickly. In business strategy, managers must also figure out the subsequent actions of other actors. However, as compared to chess where there is only one other party to consider, business strategy involves numerous parties.

When making decisions, top management teams (TMTs) must think specifically about how the following people or entities will react:

- buyers or customers,

- suppliers,

- government regulators,

- pressure groups, and

- competitors.

This is not an exhaustive list, but it does include the most prominent actors.

Example: AT&T Purchases T-Mobile

As an example, AT&T announced in 2011 that it was going to purchase its rival T-Mobile for $39 billion. AT&T’s top management, however, did not completely model the reactions of the necessary parties, as evidenced by the strong counterpressure that came shortly after the announcement. Within weeks of the March 20, 2011 press release, AT&T and its TMT were dealing with all sorts of issues, including

- customer defections because some customers were unsure if the newly merged company would offer the same plans as they currently had in place;

- U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) officials announcing a probe and lawsuit to block the merger due to antitrust concerns;

- an FCC investigation and lawsuit to block the merger due to antitrust concerns; and

- a lawsuit by rival Sprint to block the merger due to antitrust concerns.

In essence, AT&T was playing a chess game without modeling its rivals’ subsequent moves. As a result, it was forced to back out of the deal and, according to the contract, had to pay T-Mobile $6 billion in break-up fees. This led to a multibillion-dollar loss in the 4th quarter of 2011 and a $2 million pay cut to the CEO. Had AT&T thought through its moves better, it may have been able to anticipate the quite obvious reactions of other actors and allocated its time and monies somewhere more effective (Brown, 2017).

Strategic Decision-Making: Events

In addition to being able to model the actions of customers, suppliers, regulators, pressure groups, competitors, and others, management must also be aware of events that may change their decisions. We will call these event shocks, which are events that are exogenous to the firm. This means that the event originates outside of the firm and, therefore, management does not have control over it.

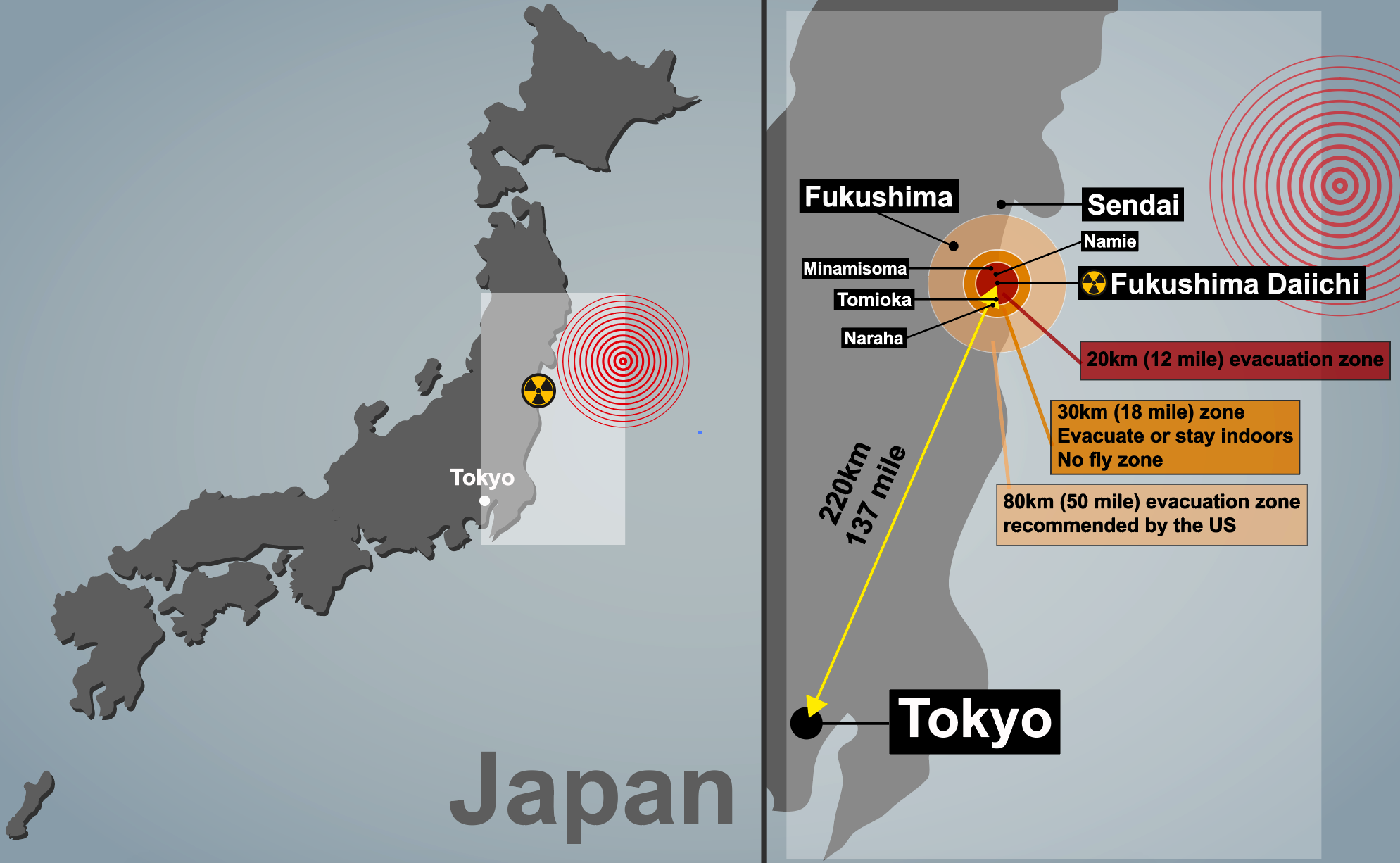

Example: Earthquake in Japan

An example of an exogenous shock would be an earthquake, which may affect the company’s operations. In 2011, a major earthquake hit off the coast of Japan, leading to a tsunami and the shutdown of a major nuclear plant. Clearly, the earthquake is outside of management’s control. So how would this earthquake affect a specific firm or industry? One interesting result of the Japanese earthquake was that many of the world’s suppliers of automobile parts are located in this part of the world. After the March 2011 event, many auto manufacturers (e.g., Toyota, Ford) could not source key parts for their production. This included the pigment and dyes that make black paint, almost all of which is sourced from this part of the world. For much of 2011, there was a shortage of black cars in the global auto market.

Two Types of Shocks

There are two types of shocks: systematic and idiosyncratic.

Systematic Shock

A systematic shock is an exogenous event that affects an entire system. In this course, a common system would be an industry. Shocks that affect an entire industry, such as an interest rate increase, are systematic.

Idiosyncratic Shock

An idiosyncratic shock is an event that has an effect on one firm but does not affect the firm's competitors.

Not All Affected Equally

Most shocks will be systematic in that events will normally not be targeted at one firm. However, just because a shock is systematic does not mean that all companies in one industry are affected equally.

Example: Auto Industry Interest Rate Increase

For example, imagine that you are studying the automobile industry and interest rates increase in a short time frame. This increase would have an effect on all auto companies, either directly or indirectly.

- Direct effect: A direct effect could be higher interest rates on the loans or bonds that the auto companies have taken or will take.

- Indirect effect: An indirect effect may be seen in lower demand since these companies' customers take out loans to purchase cars.

In this example, all auto companies would be negatively affected indirectly because customers were taking out fewer loans. However, some companies would be less directly affected than others because some of them may have needed to take out fewer loans or bonds to weather the rate increase. For example, a company that has no debt on its balance sheet and wasn't planning on taking on new debt would be able to absorb the shock better than companies that do have debt.

Not a Shock

Some apparent event shocks are actually great examples of events that are not technically shocks.

Example: BP Oil Spill

For example, the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico may at first appear like an idiosyncratic shock. However, this is not considered a shock because the event was not exogenous to the firm. The oil spill was a result, at least partially, of the company’s inability to secure its oil pipelines. In this case, the issue is endogenous and not exogenous. This may appear like a shock (and we sometimes discuss it informally as one), but it is actually a breakdown of internal controls within the firm.

What Is Blockchain? | Video

Blockchain is a newer technology that has become increasingly important to many corporations, especially within their supply chains. While you may know blockchain as the technology behind cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, it is more important to businesses outside of its use in currency. Watch Video 1.1 to learn the basics about blockchain.

Business Strategy Overview | Video

Watch Video 1.2 to get an overview of business strategy—from the perspective of both the concept and the course. You will find videos like these throughout this course, and they will introduce you to concepts such as decision-making under uncertainty, competitive environments, managerial constraints, and many others.

Business Strategy Overview

RICHARD BROWN: Welcome to B A 462, Online Business Strategy. This is going to be the beginning of our material for the semester. It is an overview of the course, but it is fundamental information. So make sure that you are beginning with the mindset that this is the beginning of the course and that this information is certainly fair game for exams, or projects, or whatever it might be, so make sure you're taking notes.

Also make sure you're getting in touch with me if you have any questions, if you need anything clarified. You've already listened to, hopefully, the intro slides, and so you know how to get in touch with me by email, text, phone, however it may be. Thanks.

There are differing views as to what the definition of business strategy is, and what I want to say is that business strategy is the study of corporate decision-making in the context of the competitive environment. And this will be kind of what we follow through with in the next slide is just kind of further defining some of these other terms.

And if I had to define the class in one word, it's competition. So business strategy is how do top managers at the corporation make decisions—so what is the process by which they make decisions—when they're considering the competitive environment. And we're going to define competitive environment, but the competitive environment, basically, is going to be the industry or the markets that we are involved in and all of the actors that are involved in those markets. That could be competitors, regulators, et cetera. We'll go through exactly who some of these parties are, but my definition would be right here. And if I had to define the course in one word, it is competition.

So what I want you to start thinking about is get yourself in the mindset of a top manager at a corporation and how is it we're going to maneuver our corporation through this competitive environment. How are we going to compete to survive?

So just like the slide says, T M T, top management team, they have to be cognizant about other actors in the competitive environment. One thing I want to make sure that we understand—the competitive environment clearly includes our competitors, but it is not just our competitors. We will talk about vertical competition this semester, which is where we're, in essence, competing with maybe our suppliers, not competing for customers but competing with them in terms of value extraction.

So when we say the competitive environment—and I have competitors listed here as number one—it could be our regulators who may be trying to extract some decision out of us, our suppliers, our customers. So when we say the competitive environment, it's more encompassing than just our direct competitors. Although our direct competitors are certainly part of that environment.

And what this slide is attempting to say is that managers aren't making decisions in a vacuum. This is not a game where you're saying, OK, I want to go acquire some company today, and let's go acquire them. That's not, obviously, how it works.

Decision-making is always going to be more of a chess match. It's going to be, if we announce that we want to buy some company, we want to acquire some company—this is just an example—what are others going to say or do? What are our competitors going to say about that? What are they going to do about that? What are our regulators going to do about that? What are our suppliers going to think about that?

And then conditional upon what these others may do, then we're going to make an optimal decision. So it's not about just making decisions because we want to do something. It's making decisions conditional on the actions and reactions of others in the competitive environment.

We're going to spend a lot of time talking about—well, I'll call it the micro external environment. I'll call it that in the 25th and basically, our industry and our industry space. So our industry is our competitors and others that are in there, our regulators that regulate our industry, the suppliers who supply to our industry. These are incredibly important actors, and in order to make effective and efficient and productive decisions, managers have to take these into account.

And I put et cetera because these are just four. I'm listing four. There are the four main ones that we're going think about. There clearly are going to be others.

But managers also have to be cognizant of events, so actors and events. And when we say events, we're going to label these shocks, and I think we know kind of semantically what a shock is. I'll define it as an event that is exogenous to the firm, difficult to predict, and imposes a great deal of uncertainty in decision-making.

[00:05:00] So a shock is going to be an event—it could be an event that we're somewhat able to model probabilistically. For example, an interest rate hike, I will talk about that as a type of shock. Interest rate hikes are a probable event where you can actually assign probabilities to the event.

What is the probability that rates move up 100 basis points—that's 1%, by the way—100 basis points over the next 24 months? Well, you don't know the answer, but certainly, you could model probabilities. And if you get enough people in the room, metaphorically, that have enough knowledge about those things, you could have a nice probability distribution that may come close to reality.

It's not that you can predict it. It's just that you can assign probabilities to it, whereas there are other things that you can't really assign probabilities. So is an earthquake of magnitude 6.0 going to hit Harrisburg in the next 12 months? Well, probably not, but you really don't know until it happens. So maybe the Japanese earthquake, tsunami, and then nuclear issue that we had in—I think it was 2011—March of 2011 may be the type of shock that isn't really able to be modeled probabilistically.

Yes, we know that that area is prone to earthquakes, and we know that earthquakes can cause tsunamis. And we know that a tsunami near a nuclear plant could cause issues at that nuclear plant. But this is one of these—not only is it a rare event, but it's very difficult to say when is that going to happen. Yes, it's going to happen in the next 100 years. OK, well, that doesn't help us very much when we're trying to make decisions.

Some shocks are really hard to predict. Other shocks are a little bit more—not easy to predict, but a little bit more easily put into a probability matrix. I say these things like probability matrix. Don't get stressed out about that. We're not really going to be working with hardcore probabilities.

But what I want you to think about—I want you to start thinking of decision-making as probabilities. I want you to start thinking about when you make a decision, the end state of the world after you've made that decision, which you don't know until the things actually happen, is a series of probabilities, and you just don't know which thing is going to happen. So start thinking about probabilities and how, when you're making decisions, you're assigning probabilities to the likelihood of that being the right way to go.

You may be terrible at assigning probabilities. That's another issue, but that's basically how we're going to start thinking about it in this class.

Now shocks can be systematic or idiosyncratic, and let me explain this. A systematic shock is maybe this is not controversial. It's one that affects a system. And idiosyncratic shock—idiosyncratic mean specific to, so an idiosyncratic shock is going to be a shock that happens to, say, in our case, one firm. It could be one person, but in this case, in our class, we're studying firms. So we would say one firm.

And so a shock could affect an entire system, or a shock could affect one firm. And we'll talk about this more when meet on the 25th, but it's very difficult to pick out exogenous shocks, pure exogenous shocks that are idiosyncratic. And I'm going to explain that a little bit more in the next slide, but most of our exogenous shocks—

And by the way, maybe I should further define exogenous. Exogenous means outside of, so exogenous would be a shock that comes outside of our industry or our firm. So clearly an earthquake is exogenous. Our firm didn't cause the earthquake to happen. Poor management didn't make the earthquake happen. It's just purely outside of the firm or the industry or whatever we're talking about.

So shocks can be systematic or idiosyncratic. Let's talk about systematic shocks. A systematic shock is shock that will affect an entire system. Let's think about a system as an industry.

I think there's 17 people in this class, so let's imagine that all of you are auto manufacturers. And there's an interest rate hike. So you're a system. You're an industry. And the interest rate hike—imagine it's a pretty decent sized hike—it's going to be a negative shock to the industry.

[00:09:45] Now because it's a shock not to one firm but to the industry, we would say that's systematic because the system is affected. So for example—this is a ridiculous example—imagine the government came out and the Federal Reserve said, we are hiking interest rates but only for Ford Motor Company. That would be a ridiculous example, but that would be an idiosyncratic shock for Ford. That doesn't happen often, obviously.

So this would be a systematic shock. Now it doesn't mean, however—just because the whole system is affected, it does not mean that every firm is equally affected. So first, let me discuss how our firm's affected if interest rates were to go up, and we're assuming we're all auto manufacturing companies.

One—if our company pays interest, if we have bank loans, if we have bond debt, or we need to get new bank loans or new bond debt, our financials are going to be negatively affected because we're going to have to pay more interest. That's one way.

And a more indirect way is that our customers will be able to afford less car. So either they'll be able to afford less car, and so we'll have to sell them a cheaper version. A Sentra instead of a Maxima, if you're buying a Nissan. Something like that.

Or at the margins, some people will no longer be able to afford cars. So instead of the Sentra to Maxima example, instead of selling 100 cars this month, we'll sell 92 cars. Either way, it doesn't really matter. They're almost basically the same thing mathematically. Either way, that's going to affect us negatively.

Now the second way will probably affect all of us relatively equally, but the first way will not. So some of us may have no debt and have no plans for debt. We may not need debt. We're just a company that has no debt. In that case, the first example about how our financials will be affected by an interest rate shock will be different amongst firms or between firms.

And so my firm that has no debt will not really be affected and yours that has lots of debt will be negatively affected. And so we'll say that's a systematic shock still, but one where certain firms absorb the shock better than other firms. And that's what we're normally going to see when we see shocks.

An idiosyncratic shock—every time you come up with an idiosyncratic shock, I want you to think about the question I pose in the next slide because oftentimes it's not necessarily a shock.

So based on what we just said in the last slide, internal shocks question mark. Internal shocks actually doesn't make any sense because a shock is exogenous. So most things that come to mind with respect to shocks, when you're talking about maybe a specific firm and you say, well, that's idiosyncratic shock—and that's fine. In a discussion that's fine to say, but let's kind of define that a little bit better. Most of these are going to be endogenous to the firm.

So let me give you an example and try to explain this better. Here's two examples. I'll give you a third example in a minute.

Volkswagen emissions problem. This is kind of one that you might come up with now. That's a shock to Volkswagen. That's an idiosyncratic shock is what some people would say, and if we're having a discussion, that's fine to say. But I think, technically, that's not true. The Volkswagen emissions problem, it might be a shock to shareholders, but it's not necessarily a shock to the firm. Why?

Well, if you know anything about the Volkswagen emissions problem, Volkswagen was trying to circumvent U.S. law, U.S. regulations, about emissions by manipulating their software so that the software would basically say that the emissions were OK when they weren't. Well, that's endogenous to the firm. There's something going on inside the firm. There are apparently engineers who are manipulating these things. And then there are apparently—I'm guessing, at least, because I'm sure that in a multibillion-dollar firm it's not just two engineers who are going haywire. I'm sure that there are managers that are either encouraging that, or overlooking it, or being negligent, et cetera.

And so we would say that this isn't really a shock. I think a lot of people would say it's a shock, but I think technically it's more endogenous to the firm. This is basically poor management oversight or poor internal controls within the corporation. And so I would say technically that is not a shock. This is more of a managerial issue.

The BP oil spill is an example I got for quite a few semesters when I used to go over this topic. And again, I understand the logic, and I understand the intuition of having that as a shock. But if we think about it, really what that is—and again, when I say it's BP's fault or something, it could be that it's not that BP was so negligent. It's just things happen. Sometimes things happen. And I don't know anything technically about that.

[00:15:00] But imagine BP has this oil spill, and people say, well, it's idiosyncratic because it's only BP. But it's not exogenous. There's something going on at BP where they weren't necessarily manning the ship—no pun intended—correctly. There's something inside the firm they're not doing the right, and then something happens.

That's not technically a shock. That's poor management. And again, poor management's too broad, but I'm just going to say poor management, or poor oversight, or poor controls.

So just to make sure that we understand exogenous versus endogenous. These are both really important concepts for the entire semester. This PowerPoint slide is labeled "Overview," but this is the beginning of the material. And these are really important things to understand about decision-making at corporations.

And again, I want you think about decision-making as a chess game. Hopefully, you've played chess or at least understand how it's played. But the idea is when you go to make a move in chess, you make the move, you keep your finger on the piece so that your opponent knows that might not be your final move. And the reason that you're doing that is that you are imagining all of the future states of the world.

Now that's more of a management term, but what do I mean by that in chess? Well, you're imagining, if I move my piece here, then my rival can do these three things. One thing is terrible for me, so I'm going to take this back and make another move. Or I move the piece and I look at the three things that the rival can do. And none of them will affect me negatively. And so therefore I'm going to keep the piece there, and that is my move.

You're modeling the conditional probabilities of your rival's actions, then reverting back to your original decision and either making the decision, like solidifying your decision, or saying I need to go back to the drawing board and figure out another move. And that's the mentality that we need to be in for this class because corporate decisions just aren't made in a vacuum.

This is I guess a figure that I stole many, many years ago. I don't even know where I stole it from, but anyways, I use it every semester. I want you to see what we're going to do over the next month and a half, and we have, obviously, three circles. They're all important. The outer circle, the societal environment—I'm going to relabel that to macro-environment.

And this is going to be—what are the macroforces? We can think about macro-national or macro-international. What are the macroforces that really matter?

And what I mean by that is, Where do I need to get information from? And one is the macro-environment. And we're going to go into this a little more in the next slide set, but the macroenvironment is the blue or purple outer circle. And it's very broad. So things like what is the national economy? What's going in the national economy, or what's going in the international economy?

And then the green circle is the task environment. I'm going relabel that in the next slide set—the micro external. So I'm going to have macro external and micro external. And the micro external or task environment is really where we're going to spend most of the semester, and this is going to be—we could call it our industry, or I'll call it our competitive space. And it's all the things I talked about in the first couple of slides, the regulators that we have to deal with, the customers that we have to deal with, our competitors. Who are these actors that matter for our decision-making?

And then of course, the red circle is extremely important, and that is the internal environment. And that is, what types of structures do we have? What types of processes within the corporation do we have? What type of culture do we have? Do we have a culture where you can question authority, or do we have a very domineering culture? What types of resources do we possess? What types of capabilities have we nurtured? Things like that, and we'll talk about that in a couple of weeks.

References

Brown, R. S. (2013). Political capabilities and rigidities: The case of AT&T's acquisition attempt of T-Mobile USA. In Capabilities, strategic intent and firm performance: An empirical investigation (Doctoral dissertation, Temple University, pp. 81–157). http://ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1446721559

Brown, R. S. (2017). Scanning and updating failure: How AT&T turned its political capability into a core rigidity. Telecommunications Policy, 41, pp. 71-89.

Rothaermel, F. (2014). Strategic management: Concepts and cases. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.