CI501:

Lesson 7

Lesson 7 Overview

In this lesson, we will learn about writing literature reviews.

Lesson Readings & Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 7 Course Schedule.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

Whether or not our questions are new to us, asking those questions enters us into existing conversations among teachers, researchers, policy makers, and other stakeholders.

These ongoing, expansive conversations are ultimately how the knowledge base about teaching and learning grows.

There's a lot to gain by taking time to do some reading, getting more familiar with what others are saying about our topic before we begin our own inquiry and throughout our data collection and analysis. Reviewing the literature helps us get ideas about what kinds of studies others have done, gather potential strategies to try in our teaching or research, and figure out how our own research will fit into or nudge the conversation forward.

Later, when we share our inquiry findings with others, including a review of the literature gives readers an overview of the conversation we've entered and provides important insight into how we made informed decisions about our own research. This last point may feel intimidating, but it's so important. As a teacher-researcher, you should thoughtfully consider how you'll bring your ideas into the public sphere and share what you've learned with colleagues in your school and beyond. Ideas left in a single classroom will never shape conversations. Teacher inquiry is one way to disrupt the notion that teachers should just close their doors and do what they know is best. We reject this claim and are committed to the idea that educators have an obligation to continue to grow in knowledge and wisdom and to share their growth with others in the profession.

Please recall the national organizations that were presented in a previous lesson (e.g., the National Association of Special Education Teachers, the National Science Teachers Association, the National Council for the Social Studies, etc.). If you reach out and talk with other professionals, how does your conception of who is a “colleague” expand? What kinds of conversations (e.g., professional journals, blogs, conferences) do these organizations help facilitate? How could you join those conversations—not just as a knowledge consumer, but as a producer as well?

Be a good scholar; cite your sources!

It is also important to cite our sources, giving appropriate credit, when we use another's idea. Later we'll discuss how to cite properly but for now, please keep this web page from Purdue's University Writing Center as an excellent source for APA citation, as is required in this course.

Finding Related Literature

- Use Google Scholar, ERIC, or Penn State’s e-journal list for different purposes. Check out the "Library Resources" tab here in Canvas.

- Keep track of your key words and try different combinations to get you more results. Once you find an article that fits well, check for any key words they've included in their piece to come up with additional search terms.

- Use the related articles you are finding to snowball; in other words, use their bibliographies to find other interesting leads. When using Google Scholar, you might also check out the "Cited by" feature. Under each entry is a link to other published literature that have cited that particular study, which may lead you to newer and related studies.

- For this class, try to rely primarily on empirical research studies (rather than reviews of theory or someone’s opinion) for the literature review section of your proposal. A quick check for this is to look for the author's description of their methods. If it's an emprical study, there should be an explanation of how they collected and analyzed data.

On the following page you will find screencasts by Penn State librarian, Ellysa Stern-Cahoy that show you how to use the thesaurus tool in ERIC, Google Scholar, and the PSU libraries' E-Journal list.

Please watch the videos and then finish reading the remainder of the lesson.

Library Resources

Our Penn State University Libraries houses many How To guides. We will focus on ERIC, Google Scholar, and the E-Journal List.

Watch Video

Please watch the following video tutorials.

- ERIC Education Resource: Finding the Right Descriptors for Your Search (ERIC is accessible via the Penn State Libraries' web page and then going to "E" when the "Databases" tab is clicked.)

- Using Google Scholar Tutorial (Access Google Scholar)

- How to Find an E-Journal Tutorial

Evaluating Sources

When conducting research ask yourself the following:

- Authority/Reliability: Is this a peer-reviewed publication in a scholarly or practitioner journal?

- Currency: Is this study over 15 years old? If it seems to be a foundational study, maybe that’s okay, but otherwise, are there more current studies that are taking up the same ideas in contemporary contexts?

- Quality/Accuracy: Is it based on well-documented materials? Do they reference other research and do they include solid evidence to back up their conclusions?

- Audience: Is the source trying to persuade you or is it an advertising source?

- Empirical: Is it a research study that uses data to make conclusions? To check for this, search the document for explanation of how they collected and analyzed data. References to these methods is often a tell-tale sign that this was empirical work.

Web Resource

Visit Penn State University Libraries' Research web page for more information on research as well as a list of resources.

Capturing Sources

Consider the following when capturing sources:

- Read the entirety of research articles you cite. This informs your project’s process, keywords, methods, analysis or just writing style!

- Pay attention to what the study investigated, what the researchers found, and how their work informs yours.

- Identify how the study is different from and similar to yours.

- Create an annotated bibliography as you read the ones that pertain most to your study. This type of writing is helpful for both thinking through what an individual study says and how it can be related to the others you're reading. An annotated bibliography is different than a literature review section in an inquiry proposal or report, but created an annotated bibliography first can be a useful strategy for thinking about the individual studies first, before you bring them together in a literature review. (This resource from Purdue's OWL provides more insight into writing in this genre.)

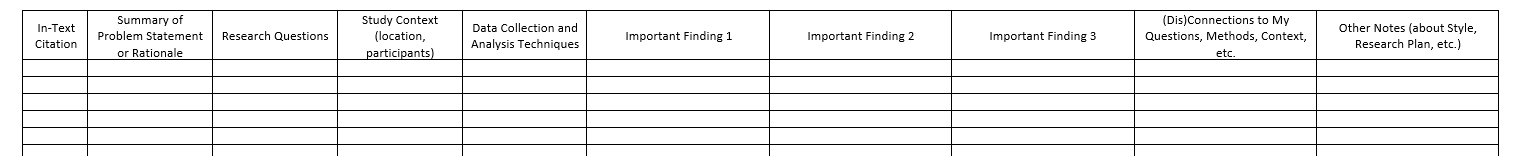

Before I begin an annotated bibliography or writing up an actual literature review, I've often found that keeping a chart like the one below is helpful while I'm searching for and reading different studies. It helps me stay organized by keeping my notes all in one place to look back at later, and I find it helps keep me focused while I'm reading each piece.

Web Resources

Make sure you're staying organized in keeping track of your source citations. There are several citation tools (e.g., Zotero, Mendelay, Endnote) designed to help with this part. The Penn State University Libraries' Subject Guides web page provides additional information on using citation tools.

CI 501 Proposal Literature Review Requirements

One important section of your inquiry project proposal for this class is a literature review. This section of your proposal will be a 5-10 page double-spaced original piece of academic writing in which you summarize published literature that is related to the research question(s) you wrote in your research plan. You should draw on at least 8 pieces of published research. These should be high-quality academic or professional literature. You will not only summarize the pieces but connect them to one another and to your research question(s) and your research plan.

On a Practical Note: Organizing Your Literature Review

Consider how the studies you've reviewed are connected. Were they asking similar questions, but in different contexts? Were they using different research designs to answer similar questions? Did they report similar or conflicting findings?

Then, look back at the studies you've read. They likely included some kind of literature review that you can look back at as a mentor text for your own writing. How did they structure that discussion? Two common approaches are organizing by theme (common findings, common approaches or questions, etc.) or by individual study.

Organize Paragraphs by Theme

“d, e, f” found that kids use writing to process school learning

Organize Paragraphs by Study

“y” study found that.....

You might try both approaches and see what works best for introducing a reader to the ongoing conversation you're bringing them into. Often, I find that organizing by study is the easiest way for me to write a first draft since it forces me to really think about what each study is offering and how it's connected to the other studies and the overall conversation. However—recognizing that reviews organized by theme are much easier for me to understand as a reader while reviews organized by individual studies very often end up feeling repetitive and list-like—I typically find myself revising that first draft to organize by common themes instead.