COMM150: The Art of the Cinema

Lesson 2: The Development of Cinematic Language

Lesson 2 Overview

Introduction

The influence of Chaplin as a character in the history of cinema is hard to overstate. The Pew Center reports indicate that the Little Tramp character is still one of the most universally recognizable icons in all of mass media.

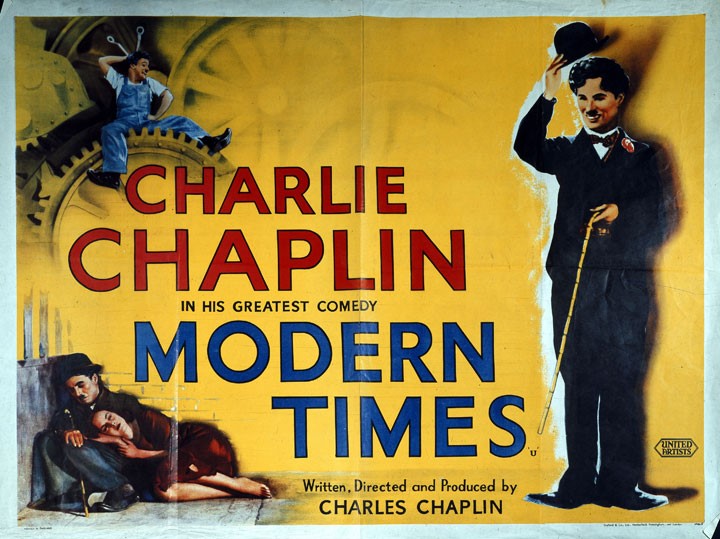

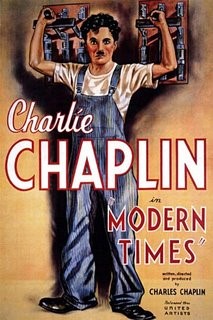

In our previews, we’ll think about Chaplin as a person, his comedic form, and about how he used these in relationship to the talking picture, which was the next big step in the innovation and technological development of motion pictures. We’ll also learn about Chaplin’s early life and view some of his older films. Once we finish watching Modern Times, we discuss the film and its implications on future cinematic language.

Objectives

Here are the objectives for this lesson.

- Describe the role of Modern Times as a social protest film against the synchronized sound film.

- Describe the setting of the film as the Great Depression and list the main concerns that echo the concerns of millions of people at that time.

- Describe the frustration felt by men struggling against dehumanizing effects of the machine in the Industrial Age as depicted in the film.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Please direct technical questions to the World Campus HelpDesk.

Charles Chaplin

Chaplin was born in London in 1889. His father died when he was 12 years old. His mother was a professional singer, and was later institutionalized. So he had to very quickly develop a very independent way of living. From his mother, he learned the showbiz angle.

With his brother, he started into the British version of what we would think of as Vaudeville in the comedy acts that were on stage. With this comedy company, he began working within London and around England. He also toured the US Vaudeville circuit. Vaudeville is a name that indicates a theater where a certain type of comedic action went on.

Chaplin worked with Stan Laurel of Laurel and Hardy fame. He stayed in America in 1912, and with his brother he started to tour the American comedy scene. In 1913, when he was 24, he joined Mack Sennett’s Keystone Film Company, and starred in many of the short films that were in that Keystone film stock. And within the first few years, he began to develop his tramp character.

At the age of 25, Chaplin turned to directing his films. His first directorial debut came with Essanay Films. He became the most recognizable person on the planet. And one could say he still remains that.

|

|

Early Chaplin Films

Please view these three Chaplin films.

Video 2.1: Making a Living (1914).

Video 2.2: Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914).

Video 2.3: Chaplin boxing, from City Lights (1931).

Chaplin as Director

Chaplin turned to directing his films when he was 25, and became a very recognizable figure and a prominent director of very commercially successful films. He began to develop his character during this time. Chaplin’s first role as the Tramp character would be in the big race in the Kid Auto Races.

Video 2.4: Clip from Kid Auto Races (1914).

Clip from Kid Auto Races Video Transcript

SPEAKER: On his first appearance in public in 1914.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

A year later, he would be mobbed wherever he went. Two years later, he would be the most famous man in the world. February 1916, Chaplin signs with the Mutual Film Corporation for the highest salary of any performer in history. Standing behind, Sydney Chaplin.

After this, Chaplin would sign the largest contract in the history of cinema with Mutual Film. Eventually, Chaplin, along with D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks created United Artists in 1919, which still exists today. United Artists was formed in response to one of the tensions that still exists in cinematic production, namely the tension between individual artists and investors. Movies are very capital intensive up front, so money people (investors) tend to dominate over production people. United Artists was designed as an umbrella for individual filmmakers and artists to be in control of their own product, and still have a distribution and production line.

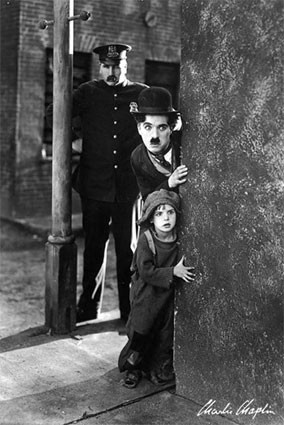

Chaplin’s first full length feature as a writer, director, producer, and star was The Kid, a 1921 film. This film was one of the most successful films of its time, traversing the world.

Silent films, especially Chaplin’s variety of silent films, were able to traverse the world because translation wasn’t necessary. Chaplin believed that cinema was a type of universal language of movement, enabling easy translation into other cultures. Instead of dubbing and subtitling films as we do now, Chaplin would complete a film and change out the intertitles. Thus, he could release the film essentially unchanged.

|

|

Chaplin as Editor

Watch this scene from the 1919 film, Sunnyside. We will discuss Chaplin’s editing techniques after the clip.

Video 2.5: Clip from Sunnyside.

We can see Chaplin’s editing efforts and his capacity to create comedic tension, which you can see by moving the guy’s hair into the fire, and focusing our attention on other things. The medium shot is used to make sure we see what is going on, while the man’s eyes are covered.

Chaplin moves from a full shot, to a medium shot, and then to an Irish shot, or close up. This is montage, editing to direct the viewer to see certain things in certain ways. Part of the comedy is Chaplin sharpening his razor, and the man thinking his throat is about to be slashed by a sharp hairsplitting razor, because he can feel something crossing this throat. Chaplin sets up the physical joke, and then executes it.

Given visual information like this, what we don’t need is a lot of dialogue. We get everything we need through the motion. Chaplin’s theory about this was that the ability to render emotion through motion was essentially the language of cinema. He worried about what talking pictures would do to that language.

The series of gags relate to the man not being able to see what is going on. A bear trap has been introduced into a situation where a man’s hair has been put in the fire and he thinks his throat is going to be slashed, and you can only image what is going to happen next. Chaplin creates expectations for the viewer by setting up the next gag. One can only think, what is going to happen to this man next?

Chaplin would use many of these same sequences later when he played the barber in The Great Dictator (1939). The use of repetition and comedic action are eminently translatable and universally appealing.

The Tramp

D.W. Griffith’s use of the Tramp was to be a threatening figure of a vagabond who doesn’t belong to society. In Chaplin’s hands, the Tramp was something that translated into a universality. As the international working class flocked to motion picture theaters for amusement in the early years of cinema, Chaplin’s Tramp touched on universal themes, such as

- Disdain for the rich

- Resistance to authority

- Resentment of modern forms of alienating labor

Chaplin’s Tramp could be of any country and any time. It was a tramp, so it was a vagabond and could be anywhere from 25 to 50 years old. The Tramp really had an everyman appeal.

The character was modeled on the kind of character one could see in everyday life, the kind of character Chaplin believed was usually unseen or a forgotten fixture of society. This is much like the way we think of homeless people in large cities today, by often ignoring them. Chaplin was using a revealing function of the cinema to show and focus our attention on this character that he thought represented the everyday everyman.

In early Tramp movies, he usually has a job, and is typically trying to join some kind of society or town at the beginning, but not usually accepted. He leaves on his own. The structure of these is cyclical. He moves in, tries to get a job, fails at that job (as he did as a barber), and then leaves that society at the end.

The movies can be seen as serial or episodic, in that the character returned and did the same type of thing in each movie. He usually ends up causing the disintegration of some part of the society through naive bumbling or carelessness. In each case Charlie is in search of only food and acceptance, and sometimes love along the way. His films lampoon the rich who step on people such as him.

Comedies are often concerned with social elements and things that people invent, such as rules for us to follow, rather than things people can’t control, such as natural parts of the world. Chaplin reveals many of these things to be absurd as he moves in and out of various social situations.

Gold Rush and Social Situations

The next clip is from Gold Rush (1925), the largest grossing film of the silent era. By this time, Chaplin was the most recognizable person on the planet. This clip has sound because it is from a 1942 re-release with Chaplin’s voice narrating. There are not only comedic elements but a very touching side as well. Chaplin believed that comedy and tragedy were never far apart. It’s touching in a melancholic way.

This is a story about falling in love with the popular girl in town, as a town outsider. He has just marshalled all his economic resources to put together a dinner. The ladies have been invited to share the dinner. He is fantasizing, as in a dream sequence about what he’s going to do at the dinner party.

Video 2.6: Clip from Gold Rush.

Clip from Gold Rush Video Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SPEAKER: And there was Georgia, caressing him with her smiles and tender glances. And the girls called for a speech, but he was too happy to speak. All that mattered was Georgia was there, Georgia. So he muttered and stuttered and finally said, I can't make a speech, but I'll do a dance. And a dance he did, with the rolls.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

The dance with bread rolls is an iconic Chaplin scene. This kind of comedy is translatable in the international market, which helped make this film the large grossing film it was.

Chaplin ends up being stood up by these callous people. So, we have this very touching and melancholic scene that perfects what it does by comedy. It is both a light-hearted story and something very serious about a man who is an outsider and cannot find his way to being accepted by the society that he wants to be a part of.

Early Sound Recording

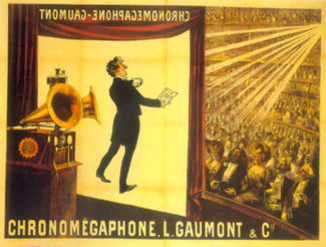

Sound was the natural innovation to come next. If the idea of art has always been to provide a mirror to nature, one of the things that people always wanted to do was to create a more complete picture of nature with sound.

During the first three decades of cinematic production, the medium was essentially a visual one. This is not to say that it was silent in the strictest sense, as movies often had orchestras giving you mood music or music to set emotional tone along with the background. There was no dialogue. There was no talking. The process of signification was essentially done with images. And technology changed all of this.

Synchronized sound was first exhibited as early as 1900 using phonographs that would be placed along with projectors. This was sometimes done in the early nickelodeon. But it would not be until the mid-1920s that it became a viable process that could be mechanically reproduced for dissemination to mass audiences and in essence where the sound could be put on the film itself.

Chaplin was the most famous star in the twenties, but he thought that talking would destroy the universal language of cinema, which in his mind was the way it rendered emotion through motion. Chaplin believed that instead of having images move across screen and things fly around, what you would have with talking pictures was shot and countershot between two people speaking dialogue. And, in many ways he was correct.

The Jazz Singer

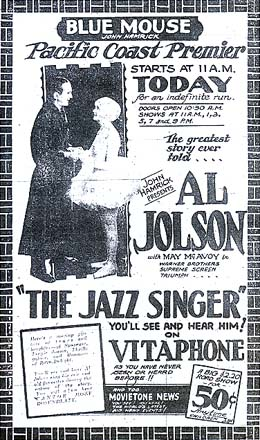

The first commercial films, a short film in this case, often called a talkie, with synchronized sound was the 1923 Phonofilm. At first, the technology was largely used to document individual personalities, like speeches given by politicians or lectures given by famous people.

The first feature length film that was distributed with sound was The Jazz Singer in 1927. If any of you have seen the film Singing In The Rain, this was a big deal. It changed the way that movies were done and it changed the way that people were cast because all of a sudden the way that a person spoke, not just how they look or emoted with their bodies, became a very crucial element in casting people.

By the 1930s the technology was essentially everywhere. Chaplin was wrong that it would be a passing fancy, and sound impacted the way in which films were made. You will see this in a bit of the short from The Jazz Singer.

Here you can see Al Jolson as the jazz singer playing in black face. This was a convention related to vaudeville. He is singing a song as a black man about his mammy down south and yet at the same time looking to his Yiddish ascetic Jewish mother in the audience.

Video 2.7: Clip from The Jazz Singer.

Clip from The Jazz Singer Video Transcript

[MUSIC - "MY MAMMY"]

AL JOLSON: (SINGING) Mammy, Mammy, the sun shines east, the sun shines west, but I know where the sun shines best. Mammy, Mammy, my heartstrings are tangled around Alabammy.

I-- I'm a-coming. Sorry I made you wait. I-- I'm coming. I hope and trust I'm not late. Mammy, Mammy, I'd walk a million miles for one of your smiles, from my Mammy. Oh, oh, oh.

Mammy, my little Mammy, the sun shines east, the sun shines west, but I know where the sun shines best. It's on my Mammy I'm talking about. Nobody else's. My little Mammy. My heartstrings are tangled around Alabammy.

Mammy, I'm coming. I hope I didn't make you wait. Mammy, I'm coming. Oh, God, I hope I'm not late.

Mammy, don't you know me? It's your little baby! I'd walk a million miles for one of your smiles, from my Mammy!

What you get in talking movies with sound is the emotional quality of the voice that is given through the presentation or dialogue. This is the kind of emotion that images themselves cannot give. You get reaction shots here to emphasize how emotional this is.

This story would catapult Jolson to international stardom, somewhat short-lived. He did a film called The Singing Fool and another. All of them had a similar conceit of a misunderstood yet eventually triumphant jazz singer. These were set in the Broadway theater district and used the power of synchronized sound to convey the emotion. The music to The Jazz Singer was by Irving Berlin. He would also become synonymous with this type of crossover of jazz into the mainstream and this is emblematic of this black-faced Jewish singer singing jazz as well.

What Can Sound Do?

So what can sound do? The desire to add sound synchronization to cinema came from a longstanding mimetic desire. Mimetic means imitative desire to basically present reality, to reconstruct a mirror of nature. Sound can change the meaning of images, just as association with other images can change the way in which we interpret an image.

Sound also allows us to hear the individuality of the performer, as the voice is totally unique, often equated with personality. We might think about the way that we use stars' voices in advertisements that are immediately recognizable. This is something that is played on in cinema. Sound allows us to hear emotion, tone, and sarcasm, all recognized in the voice. We hear the personality of the voice, and all of this is equated with the powerful persona of the star. We can see in mass media how important this is.

As an example of what sound can do, immediately recognizable. Who is this?

"The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the iniquities of the selfish."

"Blessed is he who in the name of charity"

Audio 2.1: How important is sound?

How important is sound? Audio Transcript

JULES WINNFIELD: The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he who, in the name of charity and good will, shepherds the weak through the valley of darkness. For he is truly his brother's keeper and the finder of lost children, and I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know my name as the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee.

[GUN FIRING]

Many you will recognize this from Pulp Fiction. We know this voice from seeing the film, we know without any image at all that it's Samuel L. Jackson.

Similarly to what we talked about with the Kuleshov effect, we could do this with sound. So what is this woman thinking?

Video 2.8: Kuleshov Effect 1.

Any of you who have seen the movie Jaws, this lends the baby a whole different meaning. It's no longer cute. It's somewhat menacing due to the way in which the sound is now conveying emotional content.

Similarly, what is she feeling?

Video 2.9: Kuleshov Effect 2.

If we did this with just the images, we can have any number of connotations. But with the bird sounds in this, it gives us something much more like a peaceful feeling, like she's at peace with the idea of death. So again, this is information that is associated by way of sound editing in this case.

Now let's look at the same image again, the same Kuleshov experiment. In this case, with some of the soundtrack from Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula in the background.

Video 2.10: Kuleshov Effect 3.

Instead of feeling peaceful, it might be scared or even awkward, but there is a disconnect between those two things. Sound is enormously important in terms of the kind of information that it provides for the viewers and the way in which it draws associations in the mind of the viewer to the images on screen. We could say that sound frames interpretation. We interpret the visual cues and the dramatic action in relation to the sound cues that we have. They play an important role in the creation of cinematic meaning. Sound creates a whole new way of thinking about making movies.

Sound Editing

Video 2.11: Sequence from Raging Bull.

Sequence from Raging Bull Video Transcript

ANNOUNCER: Well, certainly that was one of the most damaging evidences of punching that you have seen in recent years.

JAKE LAMOTTA: Come on! Come on! Come on! Come on. Come on. Come on. Come on. What are you standing for? Come on!

ANNOUNCER: Robinson apparently tired. Punched with a fare-the-well and rocked Jake LaMotta right to his heels.

JAKE LAMOTTA: Come on, Ray.

Now let's look at the same sequence, this time with a different soundtrack added. Focus on the interaction between these two men, the way in which they are looking at each other and staring into the other's eyes. If you add the soundtrack, in this case the soundtrack from Brokeback Mountain, what we get is a wholly different sequence of events when you're thinking about sound.

Video 2.12: Sequence from Raging Bull with alternative soundtrack.

All of this is to demonstrate that sound is very important in terms of how movies construct a relationship with us as viewers.

Chaplin's Thoughts on Sound

Chaplin's films had utilized the more universal language of motion and pantomime, and he worried about the impact that sound would have. He thought that sound would ruin film as we knew it. "Moving pictures need sound as much as Beethoven needs lyrics", he said in 1928. He thought that sound, in particular the sound of the human voice and spoken language, would likely enslave movie making to a kind of mechanization.

"Movement is near to nature, as a bird flying, and it is the spoken word which is embarrassing. The voice is so revealing it becomes an artificial thing, reducing everybody to a certain glibness." In essence, he believed that his character, especially the Tramp, would not be viable and not have the same everyman appeal that it had with the silent film. So he resisted making sound movies.

In 1931, in relation to City Lights, which he made as a silent film even though the technology had been around for four years, he said that "Dialogue may or may not have a place in comedy. Dialogue does not have a place in the sort of comedies I make. For myself, I know that I cannot use dialogue. Dialogue, to my way of thinking, always slows action because action must wait upon words."

After City Lights, which didn't fare so well at the box office given the popularity of talking pictures, he reconsidered. "Although City Lights was a great triumph, I felt that to make another silent film would be giving myself a handicap. Also, I was obsessed by a depressing fear of being old-fashioned. Although a good silent film was more artistic, I had to admit that sound made characters more present." The presence is conveyed by the spoken word.

Chaplin as a Figure

In many ways, Chaplin could be thought of as a very progressive figure, politically and socially. But aesthetically, in terms of his art, a very conservative figure, in that he continued to make silent films years, almost ten years, after the technology of filmmaking synchronized talking was around.

Here we see an old cinema short, a news film shown between features, of Chaplin arriving to cheering crowds in Europe, where he met with characters such as Gandhi. This again gives us a sense of his stature throughout Europe. It was during this trip to Europe that he took in 1931, that he would start to think about some of the impact of the global recession, which by now had reached Europe and was impacting everything about some of the issues. This would be the fodder, in a sense, for Modern Times. In this clip, you will see Chaplin with Gandhi in a window.

Video 2.13: Chaplin news film (1931).

Chaplin news film Video Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SPEAKER: Early in 1931 after the premiere of City Lights, Chaplin set off on a world tour which was to keep him away for more than a year. In London, Paris, and Berlin, wherever he went, adoring crowds mobbed him. At the time, he was the most famous man in the world. Even if he was received by those we tend to call people in high places, Chaplin had seen depression, unemployment, and despair. He'd begun to ask questions and come up with his own theories about a better redistribution of wealth.

He had discussed these theories with such eminent personalities as his friend HG Wells, Albert Einstein, and the Mahatma Gandhi, whom he met here in London. During his meeting with Gandhi, Chaplain expounded the idea that machines, when used properly, could be a boon to mankind, but employed solely for profit, they brought only misery.

Chaplin and Social Concerns

In 1931, with the Depression already a year long and many Americans already out of work, Chaplin became acutely preoccupied with the economic and social problems of modernity, the things that he felt were the most pressing of the time. After the premiere of City Lights, he took an 18 month world tour of which we saw some footage before, where he saw the impact of economic depression, nationalism, and mechanization on mankind. He read books on economic theory and began to devise and write his own social theory. He wrote, "Unemployment is the vital question. Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy and throw it out of work."

Upon returning to America, and after a conversation with a journalist in Detroit about the automobile factories and the kind of work that one did there, he began working on the scenario for Modern Times, which would encapsulate all of these themes that he would worry about, economic and social problems, and what the Depression was doing to everyday people.

|

|

Modern Times and the Tramp

Modern Times would use the Tramp for the final time to engage these pressing issues through comedy. Though, as in all of his comedies, he would have the Tramp going through a similar episodic story, but in this case, one that would reveal some of the most pressing problems of the time.

Like most of his other films, he wrote, directed, and produced Modern Times, even experimented with writing dialogue for the film, even going so far as having Paulette Goddard, who was his leading lady and wife at the time, do screen testing for her part as the Gamine, the kind of allegorical character that she played. He eventually scrapped the dialogue and chose to do it as a silent film with sound effects and musical sound track, which he wrote himself. Since he did not have to synchronize his voice, this also gave him the ability to manipulate the speed of the filming. So, if he wanted to make a film sequence more kinetic, he could crank the film slower, so that when it was shown, it would be faster, and vice versa. This gave him a lot more leeway in playing with the image because he didn't have to worry about synchronizing the voice.

|  |

The sets for the factory and the department store, the two main sets of the film, were built on Chaplin's own studio lot, part of Universal Studios, and the film took about a year to shoot. In many ways, Chaplin was an anomaly, in that he took a long time to do his films. But, since it was his money, it was OK. He was willing to make that sacrifice.

Comedy as a narrative form has certain features that we should think about. What does it do as a form of drama? It has a cyclical structure. People say that the comedic world view is one where, like nature, things always return to the way they were before. For instance, spring begets summer, which goes to fall and winter, and then back to spring. There is a certain kind of naturalism to comedy in that sense. This is captured well by the title of Shakespeare's All's Well That Ends Well. So that would be a prototypical comedic structure. Things end up well in the comedy. The world view that comedy promotes then is along the lines that things will work out in the end. No matter what the characters get into, in the end, things will be OK.

As such, comedy deals with social issues. Natural phenomena can't be, they just are. Social issues are things that people create; things which get in the way of human happiness. Comedy reveals the absurdity of these as part of its function, such as if the Tramp is being thrown out of society because of some silly rule, then that silly rule is absurd. These are two of the features of comedy, a cyclical structure and dealing with social issues.

Comedy is able to deal with certain themes in ways that other things can't. It is said nowadays that some of the best social criticism is caught in comedy, because people can accept it, whereas with people who are speaking to them earnestly or in a straightforward way, sometimes people won't accept a certain cultural criticism in the same way.

For Chaplin, he is concerned with universality. His themes are very universal. Hunger, sadness, coldness, a lack of shelter, all these things are basic themes that are dramatized as feelings for the viewer in Chaplin's comedies.

Watching Modern Times

Chaplin thought that tragedy and ridicule, or tragedy and comedy, were never that far apart. So keep an eye on, as we watch Modern Times, about how this is shown. How is Chaplin showing that proximity between tragedy and comedy, or even tragedy and ridicule?

Here are some questions to think as the basis of Chaplin’s comic appeal?

- What is the basis of Chaplin's comic appeal?

- Why do we, as viewers, identify with him and feel for him?

- How is he able to move us?

- What is it about him and his Tramp character that makes us identify with him so well?

And if Chaplin believed that the essence of cinema was rendering of emotion through motion, what internal thoughts, feelings, or desires are externalized and visualized for us as viewers? How is he rendering that emotion through motion in this particular?

Here are some themes and things to think about as you view the film. Modern Times is essentially a film in four acts, or four parts, each of which are roughly equivalent to his old two-reel comedies, about 20 minutes or so, a piece. In each of these, it's a kind of episode where he goes through a different trial or tribulation.

The impact of mechanization on mankind is a very prominent theme in the film. This is a crucial thing to think about in each of these four episodes.

- How is it treated in these different jobs?

- How was the Tramp, as a kind of everyman, able to escape the problems of modern industrial society?

- How is it possible that these problems get other characters down in the Chaplin universe, yet Chaplin, somehow, is able to stay above it, stay above the fray, and not be dragged down into the kind of nastiness like many of the other characters in his movies?

- What does he rely on in order to do that?

- What is the film trying to say about other aspects of modern life, such as domestic life? Or public life? Or labor life?

All of these things are being commented on in a comedic way. Chaplin is making important arguments, doing important cultural work here, through the genre and theme of comedy.

Finally, knowing Chaplin's antipathy toward mechanizing the voice, as we talked about his desire to not do talking pictures, it is important to note when the spoken voice is used in this film and how it is heard. In each case, it is very telling, and it is something that we'll talk about in the post-film critic’s corner.

- What is the context in which we hear Chaplin’s own voice at the end of the film?

- What is the situation, and what is he saying?

All of these things are Chaplin trying to comment on the nature of the spoken film and on the nature of this film and the way that it represents the nature of social life.

One final thing to think about as you see this film; most Chaplin films, such as Gold Rush, that followed this kind of cyclical structure had the Tramp entering society at the beginning of it, alone on the road, and ending in the same way as he began. So in the image below, you can see a typical ending of a Chaplin film. The Tramp who begins by entering into society, tries to find a job, is thrown out because of the chaos that he creates, ends alone at the end. This was part of the serial aspect of it. This is not the case in this film.

One of the things we'll discuss after you watch the film is what this means? How are we to view this in relation to the context of the film and in relation to the history and trajectory of the Tramp as a character?

Feature Presentation: Modern Times

Technology, Humanity, and Modernity

In our critique of Modern Times today, we'll try and think about some of the issues that we dealt with in the previews, including Chaplin's growing concerns about technology dominating over humanity in modernity, and the impact of a certain type of industrial production, namely Fordism and Taylorism. He saw both as being a huge problem in the modern world, especially within the context of the Great Depression. These were well under way by the time that Modern Times was made.

We'll also think about this film in relation to Chaplin's own aesthetic commitments to silent film. Remember, that Chaplin was a strangely conservative filmmaker in that he believed that sound, or at least talking, in movies would forever alter film. In many ways this film was a commentary on the talking picture. The places where one hears speaking in this film are very significant.

Figure 2.15 is a very iconic image of the Little Tramp being eaten by the machine after losing his mind.

Antonio Gramsci, a Marxist philosopher who was very interested in the impact of this new type of industrial labor that was being created in the 1920s and 1930s, stated, “The history of industrialism has always been a continuing struggle (which today takes an even more marked and vigorous form) against the element of ‘animality’ in man.” (Americanism and Fordism, 1932).

In many senses, his concern about the man versus machine, or the human versus the machine, is present in Modern Times. It’s that the machine will always be in contrast with the animal or human element to mankind.

After Modern Times, Chaplin made The Great Dictator. Many say that this was the last film that the Little Tramp existed, even though it was a different form. It was the Little Tramp as a Jewish barber. But this was a film in which Chaplin actually spoke out for the first time in. This quote is from his final speech given at the end where Chaplin was making a cry against fascism and the type of modernity associated with it.

"We have developed speed but we have shut ourselves in: machinery that gives us abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical, our cleverness hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little: More than machinery we need humanity; more than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will lost."

All these themes are also in Modern Times but rendered in a more comic way. Recall that Chaplin always believed that comedy and tragedy were very close to one another.

Framing Modern Times

Chaplin begins Modern Times with a framing montage, introducing all of the important themes that we see in the film. Pay attention to the details here.

Video 2.14: Modern Times framing montage.

This is the ironic commentary on the constitutional ideal of pursuit of happiness, showing men as herds of sheep moving toward a factory that dominates their experience of time in which the machines dominate over them. This idea is established by the dissolve of the sheep into the men streaming out of the subway and by the spatial relationships of people to machines. In a movie that is very reflective about sound in modernity, the music is driving and rhythmic, like the rhythms of the factory that it's trying to represent. Chaplin wrote the music himself.

The only other soundtrack in this, the horn, is post production sound, because this was all recorded in silent mode. The sounds are imperatives saying begin to work, stop working. This is the way that mechanized sound works for Chaplin.

Yet even in this opening montage, with all of its concerns about machinery dominating over men, we see a quick nod to the spirit of resistance, the idea of challenging the routine and standing out from the herd. In the center of this frame, we see a black sheep.

A black sheep is somebody who is standing out from the herd. This is an allusion to the character that Chaplin is going to introduce, the Tramp character, the character that cannot fit into the modern herd of man.

As in the other Chaplin films, Modern Times is a film that uses stock characters, in allegorical types. This helps us read Modern Times as an allegory because these characters are allegorical types. And in many cases in Chaplin's films, we have these abstract names to point our attention to that. In this film we have these characters:

- The Tramp

- The Gamine (a love interest)

- The Big Boss

- Big Bill

- The Sheriff

Chaplin's comedy is based on exaggerating characteristics so as to draw attention to them. These are the allegorical types that one might bump up against in modernity, Chaplin seems to be saying.

In the Factory

The first idea that Chaplin takes on as he brings us into the factory environment is the question of modern management principles. This is often called either Fordism or Taylorism and is based on the people whose writings modern management styles were derived from. Fordist principals of scientific management were derived then from the writings of Frederick Taylor, which stressed studying what was necessary for production and systematically reducing every action in the factory to its most efficient form. Standardization and homogenization, it was believed, would lead to quicker productivity and assembly line mass production would therefore produce more profit. This was a principal of management that was what made mechanized production, or what we might think of as line production, possible.

Chaplin however, as an artist and somebody who valued imagination and the creative spirit, felt that this mode of production tended to dehumanize workers, treating them as cogs in the machine, and make their humanity less important than productions. This is the notion of dominating over the human elements with ideas of profit and production.

Chaplin saw this wholesale assault on freedom and imagination to be the great tragedy of modern times. This is in a lot of his films, but most specifically here, showing us Chaplin's take on the nature of management on the people who run these systems that dehumanize workers. The character of the bosses begins early and throughout. Watch this clip of the Big Boss.

Video 2.15: Big Boss from Modern Times.

Big Boss from Modern Times Video Transcript

[WHIRRING]

[ELECTRICITY ZAPPING]

[BELL RINGING]

ELECTRO STEEL CORP PRESIDENT: Section 5, speed her up. 401.

[GEARS CLICKING]

So what is the big boss up to here? Again, the details are very crucial. The big boss is a man of leisure. He's leisurely working on the crossword puzzles, and on his own puzzle here, and reading the comics. And the comics itself, here it's Tarzan who's a modern man raised by apes, pointing to that disconnect between modernity and natural man.

So before the work day begins, this is what the man of leisure does. We know that his health is bad. His secretary brings him an aspirin. And his jobs seems to be not to work, but rather to survey and, by using modern technology, monitor the work of others, and to essentially demand more speed.

Note the sounds here. Chaplin was very concerned with the intrusion of sounds into motion picture. We had the buzz of electronic TV gadget here, and the whir of the machine which increases with the speed of the machine. There's an alarm bell, and then a mechanized voice of the big boss who's barking out orders.

The times where we hear people speaking in this film, it's always in this imperative tone. The only time the big boss ever speaks is through this mechanized media of the loud speaker and the television screen. And whenever he does, it's to order people around. This is very different than something like art. Here we see it is an imperative to be faster.

Enter the Tramp

After seeing the big boss who is running this whole show, we then see the Tramp, the person who is subjected to this modern machine, appearing as a factory worker. Remember we said part of the way that the Tramp works is in each film, the Tramp appears in a new setting and is subjected to the environment that he's working in. Here, he is subjected to this mechanized environment. And what happens to him, in a sense, is what Chaplin believes is happening to mankind in industrial modernity.

What is the Tramp up to in the next clip? Like the others, the Tramp is a slave to the work day clock, the same clock that Chaplin showed us in the framing montage in the beginning. The speed of the machine dominates over him. And what we see here is something that Chaplin had read about, which is the deleterious nature of repetitive work, the kind of work associated with industrialism. It's shown here to have a direct impact on his body.

Chaplin is commenting not only on the nature of industrial work, but on how the Tramp, as the embodiment of the human spirit, is incompatible with the demands of modern industrial work. Not only do we look at what is done to him as an individual or the body, but also what it does to social relations, both the inner and inter-relations between the different characters.

Video 2.16: Assembly line scene from Modern Times.

Assembly line scene from Modern Times Video Transcript

ELECTRO STEEL CORP PRESIDENT: (ON LOUD SPEAKER) On bench 5, attention foreman.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[GEAR CRANKING]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[BELL RINGING]

In this clip, we have all the same elements of the sound being used for impact without having the voice. But, still the main information is conveyed through the pantomime. Here we have the human versus the machine. If the Tramp is meant to embody something profoundly human, we see that his human needs are at odds with the assembly line production. For instance, when we see in that scene, the need to itch, or swat a bee, or stretch, which we might say are all supremely human needs, clash with the need for increased speed and production. When he does pause, he literally halts production and brings on punishment from management. Management here seems to be only about surveilling others work, instead of working themselves.

The rest of the men here are set at odds with one another. They have all been trained to submit to the machine rhythms. And they resent the Tramp, in a sense, for his humanity.

Chaplin is showing us that men are set at odds with one another by the bosses who subject them to this type of alienating form of labor. The Tramp immediately then, after this scene, shows the physical signs of this struggle against the machine.

The Human and the Machine

Video 2.17: Work break from Modern Times.

Work break from Modern Times Video Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[DING]

ELECTRO STEEL CORP PRESIDENT: Hey! Quit stalling. Get back to work. Go on!

[DING]

This sequence shows Chaplin's criticisms of modern mechanization in its various forms. It begins by visualizing the psychological imprint, this conversionist area or ticks that remain after he stops his repetitive work. A man quickly takes his place, so the production can continue unabated. It’s interesting that he must clock out, in other words not earn wages, to use the bathroom here.

When he does try to do something supremely human and relax, the music is changed to something more soothing and less rhythmic to remind us that this is what he's trying to do. The big boss appears on the screen and screams. This is rendered through rear projection, and it gives us an almost Orwellian take on management. Management here is always watching and disciplining any expression of humanity.

The critique of visual mass media here is very prescient, almost Orwellian in its take. This is before the book 1984. The big boss in the bathroom is a nod both to the talkie, the screened image barking orders at the audience, and to the TV which was a new invention in 1936.

Chaplin believes both are an intrusion into private life. The big boss on the screen is menacing, coercive, and maligning. Chaplin uses talking pictures, dialogue, to voice the imperative commands of the boss. As opposed to his more poetic motion orientation to his films, talking is always about barking orders to us. This is part of Chaplin's critique of the voice as it would appear in film.

Other Voices - Machine Sales

Other voices in Modern Times are important as well. For instance, we hear the voice in the machine sales sequence.

Video 2.18: Mechanical salesman from Modern Times.

Mechanical salesman from Modern Times Video Transcript

- Good morning, my friends. This record comes to you through the Sales Talk Transcription Company Incorporated. Your speaker, the Mechanical Salesman. May I take the pleasure of introducing Mr. J. Widdecombe Billows, the inventor of the Billows Feeding Machine, a practical device which automatically feeds your men while at work.

Don't stop for lunch. Be ahead of your competitor. The Billows Feeding Machine will eliminate the lunch hour, increase your production, and decrease your overhead. Allow us to point out some of the features of this wonderful machine-- its beautiful aerodynamic streamlined body, its smoothness of action made silent by our electro-porous metal ball bearings. Let us acquaint you with our automaton soup plate, its compressed air blower, no breath necessary, no energy required to cool the soup.

Notice the revolving plate with the automatic food pusher. Observe our countershaft double knee action corn feeder with its synchro-mesh transmission, which enables you to shift from high to low gear by the mere tip of the tongue. Then there is the hydro compressed sterilized mouth wiper. Its factors of control ensure against spots on the shirt front.

These are but a few of the delightful features of the Billows Feeding Machine. Let us demonstrate with one of your workers, for actions speak louder than words. Remember, if you wish to keep ahead of your competitor, you cannot afford to ignore the importance of the Billows Feeding Machine.

What we're seeing here is mechanically reproduced speech by way of the phonograph that is being used to sell products. This is not to communicate on a human level, but designed to streamline selling.

This, for Chaplin, is doubly a problem, because in all of his films, the most human thing that there is, is eating. Many critics and people who loved Chaplin all commented on how this is his dominant desire in all of his films, because it's the most human thing that we do. In Modern Times, as is seen in all Chaplin's work, most of the Tramp's motivation comes from hunger. This is the most basic and universal human need.

The feeding machine, which is actually not that far off from several things that theorists of scientific management were offering in their writings, is sold not the basis of its goodness or its humanity, but its efficiency and its bottom-line value for competitive productivity and profit. And as the machine says, actions speak louder than words. What we get with the feeding machine, as you remember from seeing the film, is something that proves how impossible this is with somebody human, like the Tramp.

The Radio: Smells like Commerce

Video 2.19: The Radio Sequence from Modern Times.

The Radio Sequence from Modern Times Video Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[STOMACH GURGLING]

[DOG BARKING]

[STOMACH GURGLING]

[DOG BARKING]

[STOMACH GURGLING]

RADIO ANNOUNCER: If you are suffering from gastritis, don't forget to try--

[STOMACH GURGLING]

[SPRAYING SELTZER WATER]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

You can see Chaplin using sound as part of a gag. He was not against sound in pictures. Again, mostly just against the voice, dialogue, in movies. The talking in talking pictures.

Chaplin wrote in his autobiography of his lifelong revulsion towards the ethos of advertising and commercial propaganda heard in mass media society. He blamed it, as he said, for the gradual dissolution of Western culture. Our decline and fall is not the result of politics, revolutionary armies, Communist propaganda, rabble-rousing, or soap-boxing. It's the soap wrappings that are conspirators. Those international advertisers among which he listed the media, radio, television, and motion picture.

So here, the cure for the indigestion that is heard in the scene is to turn on the radio. And what we hear, then, is a commercial for if you have gastritis. So these two hostile sounds are linked by association here, and one could say that the sounds of the advertisements is worse than the problem of the sound of the stomach, that the Tramp would rather have quiet here and turn it off.

Through the prissy pastor's wife, we get a sense of Chaplin's famous antipathy toward religion. Chaplin seems to say that these kind of religious people embody a kind of bad faith that Chaplin saw in religion.

Humanity in Modern Times

So along with eating, there are other important things for Chaplin and in Modern Times. Things that are the human things that he wants to preserve. The comedy of Modern Times was more concerned with making fun of the social conventions and behaviors that push the Tramp around. This is one of the things that comedies do, is comment on the rules that people make for each other.

The thing that remains important for Chaplin here, and the things that the Tramp cares about, are these very, very basic human needs. Food and hunger would be primary ones. Here are several scenes where Chaplin is showing us the necessity of eating, and the importance of eating for the Tramp.

Video 2.20: Food and hunger, the Tramp against the big guy.

Video 2.21: Food and hunger, the gamine steals bread.

Video 2.22: Food and hunger, the Tramp finds his way back to jail.

Eating in the age of machines is something that is one of the last human things available to one. When we get back to the food machine, eating is still a necessity in Modern Times, even in the Taylorized factory, but it’s reduced to a function, instead of being something human. Note the big boss in this upcoming scene, that he doesn't reject the feeding machine because it strips the human being of his dignity. (What the Little Tramp has to go through here is pretty humiliating, and reduces the human to an automaton.) It’s rejected because it's not practical. In other words, it's not going to help the bottom line of factory production. The big boss is, as other management principles are shown to be, kind of against the human.

Note the sound editing. What we get are the sound effects, the kind of ambient buzz, and the electronic whirl. These things that are dominating over human life.

Video 2.23: Modern Times eating machine.

Chaplin seems to be arguing that while the most human need, eating, is sacrificed to productivity, the human being is also always sacrificed to the machine in an industrial society. He's visualizing this logic explicitly through the following surrealistic sequence, and by surrealism, meaning the kind of artistic trend that, as associated with the 1920s and 1930s, was supposed to kind of represent the overly real element of dream works, or dream sequences.

Into the Machine

In the following scene, which is the most iconic from the film, the speed of modern production quite literally pulls the Tramp into the machine. Interestingly, the machine looks a lot like the inside of a film projector, and leads to a nervous breakdown. The sequence is said to have been inspired by Chaplin's conversation with a journalist in Detroit, who had described to him how the factories lured healthy men off the farms, who became nervous wrecks after a couple of years working on the assembly lines. Here, that idea is rendered explicitly through a kind of surrealistic sequence.

Video 2.24: Modern Times into the machine.

Modern Times into the machine Video Transcript

[BELL RINGING]

[MACHINERY WHIRRING]

ELECTRO STEEL CORP PRESIDENT: Section 5, give it a limit.

[GEARS CLICKING]

[MACHINERY WHIRRING FASTER]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[GEARS CLICKING]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

This is one of the most iconic scenes in cinema history, and one of the most trenchant criticisms of modern society in cinema. Interestingly, when he emerges again, he's lost his sanity. He's freed from the pressures of time and work rhythms. And whereas the other men are still trying to stop him and keep production going, i.e., remain trapped in the roles as cogs in the great machine, the Tramp is graceful and playful, in the way that he's dancing around.

You can get a sense of why W. C. Fields, the great comedic actor of the 1920s and 1930s, once referred to Chaplin as that goddamn ballet dancer. You see his physical grace. It could be said that in a way, it's impossible for the Tramp's very human body to exist in the same space as a machine. One of them, in a sense, has to give. The spirit of humanity triumphs. The Tramp frees himself, begins to dance, and eventually shuts down production before being taken away.

Madness and Taken Away

Video 2.25: Modern Times madness and taken away.

As Chaplin transforms a factory into his personal playground, the factory machines break down. Note that his dance includes spraying oil on the other workers. This visualizes the extent to which the men who submit to such inhuman labor become cogs in the machine that need oil, as it were.

Leaving the Hospital

Watch this clip from Modern Times.

Video 2.26: Modern Times leaving the hospital.

Labor and the Police

This clip is from the second episode of Modern Times, where the Tramp comes up against the question of labor.

Video 2.27: Union busting in Modern Times.

Strikes and Prison

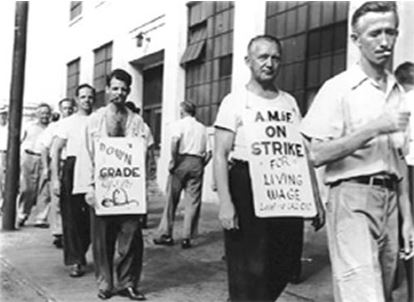

It's interesting that the law or police officers end almost every sequence and has every possibility of happiness for the Tramp. Here, as elsewhere, the law is the protector of private property and the interest of big business, not the protectors of justice. This was not only something that you see in Chaplin's films in general, but it was also a very popular sentiment in the 1930s, very widely held. Note how the law here is represented in relation to the question of labor and the right to organize.

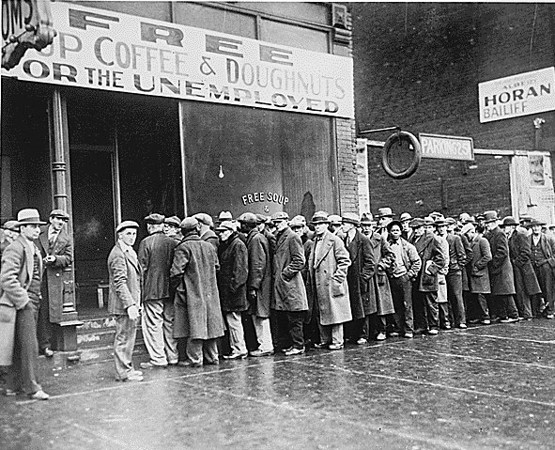

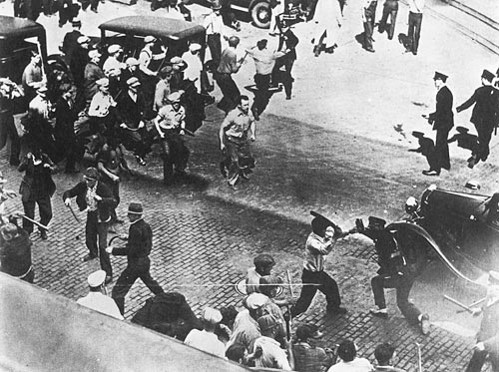

Figures 2.17 through 2.20 show photos of the 1933 mine strike, bread lines, a communist protestor, and the general strike in San Francisco in 1934.

|

|

|

Figure 2.19: 1934 San Francisco general strike. |

|

These were things that were everywhere. Chaplin is using comedy to comment on things that were pressing on society, he believed. With the Tramp ending up every sequence, he ends back in a place that seems to be better than living out in the real world with all its excitement, which is prison.

The irony is that Chaplin doesn't want to leave prison. The warden is telling him, after your good work, you can go. Chaplin is saying I'm so happy here, I don't want to leave. I have everything I need here. The Tramp is somebody who is mostly concerned with having his basic human needs met, which are food and rest and warmth and shelter, and now he has to go back out and struggle in the outside world.

The Gamine

It’s at this point where the love interest starts entering into the story. In comedy, it is necessary for lovers to be compatible. This is one of the constant features of comedy. In order for the comedy to resolve, the two love interests have to get together at the end, and they have to be compatible in order for society to be reconciled.

In this case, the gamine, the Claudette Colbert character, is a female version of the Tramp. She is, like him, a vagabond. She is a free spirit. In a sense, she's even more anarchistic and defiant than the Tramp is. She alone, of all female characters in the film, has shed her social mores and conventions. Like the Tramp, her motivation is always food, and Chaplin seems to be saying here, as elsewhere, that illegal acts like stealing, looting, or squatting are rendered morally justifiable by the conditions that one found during the Depression.

It's interesting that she's quite young for an older man. Recall we said that the Tramp could be anywhere from 20s to 50s, but here we know from the storyline that she is on the lam from the juvenile authorities. So people have made a lot out of this, because Chaplin was actually involved with several very young women himself, like Roman Polanski later was. This could lead you to a little bit of a psychoanalytic reading. But, within this film, what it tells us, is that the Tramp is an eternally young spirit, and their relationship is largely very chaste.

Video 2.28: Introducing the gamine in Modern Times.

With love interests, however, come something that is difficult for the Tramp, which is giving up his individuality for something like normativity. Once the relationship with the gamine is established, the Tramp has a motivation that forces him into situations that he is ill-suited for. In other words, he wants to have the material means to have a home and provide for her, so he's forced to get a job. And this is something that the Tramp doesn't like very much.

The commentary on home here rejects the rampant materialism that Chaplin saw as a feature of modern life. The rampant materialism is something that he comments on quite a bit in the department store sequence, as well as in the scene where the Tramp and the gamine fantasize about the bourgeois suburban existence, which we see here.

The Fantasy Home

The fantasy that Chaplin wants is one that exists by way of ignoring reality. The couple is able to have their normative fantasy because they are able to ignore the two victims of depression who are out on their front lawn. This is indeed a capacity for concealment in the face of poverty that Chaplin is using the revealing function of cinema here to fight. Indeed, the only time in which the two find a home in the film is a squatter town, which is an allusion to the social phenomenon that was very easy to see during the Depression.

Video 2.29: Fantasy home sequence from Modern Times.

The Realistic Home

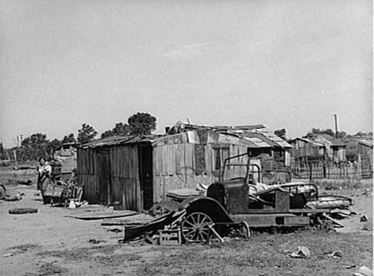

There were small villages in Central Park, New York City filled with the very same type of shacks that Chaplin gives us in the film. Figure 2.21 is a picture of a squatter town in New York City which looks very much like the squatter town that Chaplin is rendering in the film.

Watch this clip of the Tramp leaving his home searching better conditions.

Video 2.30: Squatter home in Modern Times.

Chaplin shows the Tramp leaving his modest home in search of better material conditions, out of love. He enters the workforce again. He goes back to work at a factory. But again, we see the Tramp's inability to occupy the same space in the film as a machine without destroying them.

This is not what thwarts his plan to get a better house for his love interest. This time, the plans are thwarted by forces that are beyond his control. The factory, of course, is shut down by labor strike. This is a kind of irony that the people who are wanting to get back to work, the unions, shut it down almost immediately.

This is an introduction of an absurd ending to his attempt to find work in the industrial labor market, where he's the machinist's assistant. This essentially shows that Chaplin was ambivalent about unions, just as he was ambivalent about other features of industrial mechanized society. As is in all the other episodes, this episode ends up with the Tramp back in jail.

What we've seen each time is that when the Tramp tries to enter into the modern workforce, his incompatibility with modern forms of work, his need to play and to dream, in other words, to be very human, all of this forecloses integration into the society.

None of the jobs last long.

- The factory job lasts half a day.

- The dock job lasts five minutes.

- The night watchman job at the department store lasts one night.

- The mechanic's job lasts half a day.

The normative desire to hold down a job in modern society in pursuit of happiness, you might say, does not seem to fit with his free anarchistic spirit. Each segment ends with him back in jail. Every time he's unable to enter the modern world and be happy, Chaplin seems to be saying to us that humanity and the modern world don't go together.

It’s while he's in jail the final time that the gamine is discovered dancing to the music of a carnival. She gets a job as a dancer in a dance hall, and this opens up the possibility for the Tramp and the gamine earning a living in the one form of work that Chaplin seems to be saying values imagination and free spirit, which is entertainment. But, there we see that even art is commodified as the gamine's free dancing becomes something to be marketed by an entrepreneur.

The Tramp is Finally Heard

This leads to the final sequence, where Chaplin is heard for the first time. We've discussed his resistance to the talking voice, and to saying that he didn't think that the Tramp could ever speak. The ways in which voices are heard in Modern Times are always less than human, and usually, one-way communication. Authority such as using mediated communication to bark orders at the little guy, or the imperative of the radio to buy stuff for your bad stomach. All of these things are the way that Chaplin thinks Modern Times is using the human voice.

Chaplin wrote of the pressure on him from the movie industry to have the Tramp speak. He said some people suggested that the Tramp might talk. That was unthinkable, for the first words he ever uttered would transform him into just another person. Besides, the matrix out of which he was born was as mute as the rags he wore.

By talking, Chaplin worried, he would become just another comedian. He would become just like one of the people who was talking, you know, the other films, and his individuality, his uniqueness as a character, this Tramp character, would be lost. Chaplin's solution to this was to introduce the Tramp talking in gibberish, his famous gibberish song. And this display is the art of pantomime in its fullness. Here is the gibberish song scene.

Video 2.31: Gibberish song scene from Modern Times.

Gibberish song scene from Modern Times Video Transcript

[MUSIC - CHARLIE CHAPLIN, "CHANSON INCOMPREHENSIBLE"]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

[NON-ENGLISH SPEECH]

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: [NON-ENGLISH SINGING]

Sing, Never Mind the Words

The intertitle we saw, sing, never mind the words, is very significant. Whereas the spoken word in the rest of the film seems hostile to human life, Chaplin's nonsensical singing, is based on a number of word sounds more than anything else. You hear some French, some Spanish, and some Italian, which may indicate that this is Chaplin's view of the Esperanto quality of cinema.

All this brings forth a moment of utopian community and possibility. Yet, it's very risky as well. The other utterances in the films are all indirect, mediated by way of the phonograph, the loudspeaker, the TV, or the radio. Here his utterances are direct and provoke an intimate response. The song is a mix of different languages, including some that are comprehensible in English. Yet the meaning of the song, about a rich old man and a tart, seems clear to the audience. It’s the language of action, of expressive visual and corporeal signification that is universally comprehensible.

Chaplin, as he did in City Lights, seems to be arguing that significant communication can occur without the spoken word. Of course, this is only momentary happiness and acceptance into society, because immediately after this, the law serves a warrant for the arrest of the gamine, which you see in this intertitle. What we have seen up to this point, is that the film is both satirizing and parodying many elements of modern life, and seems to be saying that modern life, with its enslavement to mechanization, its foreshortening of time, and its foreclosing of imagination, is incompatible with the Tramp, who represents something very supremely human.

Breaking the Tramp Mold

In other comedies, such as the Shakespeare comedies, the things getting in the way of the lovers coming together at the end have to be exited, stage left. But, what we have here is the Tramp has to leave society. Chaplin seems to say society cannot be redeemed. In all Chaplin’s films, save Gold Rush, the Tramp leaves the society that will not accept him, and heads out to the road. This is part of the serial logic of the Chaplin films. He tried to enter society, he gets beaten around, ridiculed, and eventually leaves by himself.

This was originally going to be the case with this film. The ending had Chaplin back in prison after this scene, and then when he got out, he would find the gamine again. This time, however, she was a nun. This was the first take on this. But, Chaplin is famously hostile to religion, and here he had religion cloistering her free spirit, and then she would leave the Tramp left to fend for himself.

Chaplin felt this was too pessimistic, given the current of the times, which was the Depression. This was to be a pretty negative view of the outcome of things, two free spirits who can't find compatibility. One of them has to leave society, and the other has to become a nun.

Instead of that ending, we get this ending.

Video 2.32: Ending of Modern Times.

This is the social message of the film. Things may be hard, but as the intertitle says, buck up, never say die, we'll get along. This was the original music that Chaplin composed. The song was called Smile. We have Chaplin walking off into the sunset with his love interest. This is a much more optimistic ending than Chaplin gave us in any of his other films, and in a sense, this is not only the exit of this character from this film, but the exit of the Tramp from the motion picture industry.

Final Thoughts

Modern Times argues that the free-spirited human being seems to be incompatible with modern industrial civilization. The two, in a sense, cannot mutually coexist. Yet here, Chaplin is offering a sentiment that seems to call for solidarity and companionship as the antidote for modernity. So the equality, at least in spirit, of the two characters, makes this a kind of ending onto the perpetual road of life analogous to what we might find in a buddy film, a type of genre film. But this is the last time that you would see this. For the last time, the Tramp's call for optimism and hope in the face of every problem that life can hurl his way touched audiences. Comedy and tragedy are never that far apart in the Chaplin world, and he seems to remind us of that here. It is only worldview that separates comedy and tragedy.

Though many of the critiques of modern mass media society would be leveled again a couple of years later in The Great Dictator, this was the last time the Little Tramp would be seen in a film as the Little Tramp. Chaplin seemed to be acknowledging, or at least seemed to know, in a sense, that in a filmic universe now populated by talking stars and the dialogue-driven picture, the Tramp could no longer exist.

In a sense, this has to be a buddy film between a very chaste Tramp and the gamine, because she's underage, and it would maybe be a little too creepy (it's good to remind us of this) with his modus operandi in discovering talents. He first married a sixteen year old, then married a nineteen year old, and repeated this many times.

All of these elements are in there to think about. In summation, Modern Times is arguing that, in a sense, humanity, in the form of the Tramp who allegorizes humanity in all of Chaplin's film, is incompatible with modern industrial civilization. The cinematic universe, the cinematic world, the world of Hollywood, was also being determined by that technology. The Tramp, in a sense, could no longer exist.

In leaving, something to hear would be a version of the main theme song, Smile, as done by Nat King Cole.

Audio 2.2: Smile written by Charles Chaplin, performed by Nat King Cole.

Smile written by Charles Chaplin, performed by Nat King Cole Audio Transcript

[MUSIC - NAT KING COLE, "SMILE"]

NAT KING COLE: [SINGING] Smile, though your heart is aching. Smile, even though it's breaking. When there are clouds in the sky, you'll get by. If you smile through your fear and sorrow, smile and maybe tomorrow you'll see the sun come shining through for you.

Light up your face with gladness, hide every trace of sadness, although a tear may be ever so near. That's the time you must keep on trying. Smile, what's the use of crying? You'll find that life is still worthwhile if you'll just smile.

That's the time you must keep on trying. Smile, what's the use of crying? You'll find that life is still worthwhile if you'll just smile.

Lesson 2 Wrap

Summary

Charles Chaplin’s influences in the history of cinema are hard to overstate. Chaplin’s comedic form and how he used these forms was very influential in relation to the talking picture, which is the next big step in the innovation and technological development of motion picture. Modern Times was an influential film on future cinematic language, as well as serving as an argument that the free-spirited human being seems to be incompatible with modern industrial ciivlization.

Check and Double Check

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Coming Attractions

In the next lesson, we will watch Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, discuss director Frank Capra and his use of populist cinema, and begin to explore the studio system during the Golden Age of Hollywood in the 1930s.