COMM180:

Lesson 2: Origins of Mass Media

Lesson 2 Overview

Introduction

Lesson 2 focuses on the origins and historical development of telecommunications and mass media, from as far in the past as prehistory to the most recent events. It will help you learn the history in a systematic way and understand the milestones that have led to our current situation.

Objectives

Here are the objectives for this lesson:

- Discuss how advances in communication technologies, such as writing and the printing press, have influenced civilizations.

- Understand the evolution of media in agricultural and industrial societies.

- Understand how emerging communication technologies are changing the way we live and work.

- Discuss how our modern information society has influenced our consumption of media.

- Identify the components of the SMCR model of the communication process.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Please direct technical questions to the IT Service Desk.

Language and Complex Communication

One of the defining features of human beings is the capacity for language and complex communication. Other animals can communicate at a very basic level, but it is believed that only humans have the capacity for abstract thought. Humans developed language more than 40,000 years ago. The next significant technological advance was the invention of writing about 5,000 years ago. Writing had four significant benefits:

-

Information Storage

Knowledge was no longer limited to what a person could remember. This change also helped make information more permanent and more transportable.

-

Accuracy

Writing significantly improved accuracy. Think about the childhood game of "telephone" where you whisper a sentence to a friend, who then whispers that sentence to the next person and so on. The message is radically altered after being communicated to just a few people, and the original sentence is lost forever. Writing allows the message to be stored and replicated accurately. With hand copying, errors still get introduced over time. Printing eventually allowed for perfect copies of the original message.

-

Complexity

The ability to store information and refer back to it allows for the development of more complex ideas. Think about trying to solve a difficult word problem in your head without writing it down! Writing allows for dramatic advances in knowledge and scientific discovery.

-

Control

Writing allows us to communicate instructions and coordinate activities more easily. Writing makes it easier for a government to issue orders to its army and its citizens, especially over large distances. Leaders of the ancient world depended on writing to manage their vast empires.

Reflection Question

How do governments today use various forms of communication to maintain control over society?

Printing and Unintended Consequences

Contrary to popular belief, the printing press was developed in China more than 400 years before Gutenberg's famous press in Germany. Why do we associate printing with Gutenberg and Germany instead? The main reason is the difference in language. The Chinese language consisted of thousands of complex symbols called ideograms. There were so many different symbols that arranging them in molds to print different books was impractical, even after the development of movable type. When Gutenberg developed his printing press in 1450, he relied on the Latin alphabet, which only had about two dozen different characters. This alphabet made it much easier to manage the fonts and rearrange letters to print new books. This comparison demonstrates how the same technology will develop differently under different cultural circumstances.

Printing also provides a good example of how new communication technologies have unintended consequences. Printing made books much cheaper to produce and therefore more affordable for consumers. As the cost of books declined, more people learned how to read. One of the first books to be printed was the Bible. Initially, printers and the Catholic Church thought that making more Bibles available would increase religious devotion and strengthen the power of the Church.

Ultimately, as more people owned and were able to read their own Bibles, they began to question the teachings of the Church. Whereas before people had to rely on priests to explain what the Bible meant, now people could read it on their own and develop their own interpretation. The printing press was also used to publish pamphlets that questioned the authority of the Church leaders. Eventually, the Reformation led to a major split in Christianity. While it was not the only factor, the development of the printing press played a large role in this split. This consequence was definitely not intended by Gutenberg when he printed his first Bible!

Video 2.1 provides some more insightful and thought-provoking ideas about the impact of printing:

SPEAKER: CLAY SHIRKY, PROFESSOR OF NEW MEDIA, NYU

[ON SCREEN TEXT: HOW HAS TECHNOLOGY CHANGED THE ROLE OF THE PUBLISHER?]

CLAY SHIRKY: When Gutenberg and his followers perfected movable type, you suddenly could produce much, much, much more material than ever before.

So they printed a lot of Bibles. And then all of a sudden Europe had all the Bibles it could use in any given year, something that had never happened before. And so they had this huge amount of excess capacity and no new material that needed to be printed. And the solution they hit on was quite world-changingly dramatic, which was they decided to start printing books that no one had ever read before. We have the word novel to describe novels because the word comes from a novelty itself, was new.

Almost any book you would want to print in 1400 was a book that had been venerated for 1,000 years. By 1500, you've got stuff that is literally hot off the presses. The down side of this is that if you're printing a book that no one has ever read before, maybe no one wants to read it, and there's no good way to know. But you've got to print all the copies in advance to sell them. And if you don't sell them, you're out all the money. And if you do that a couple of times in a row, you're out of business.

So all of a sudden the printer, whose main responsibility was operating this piece of equipment, became the publisher whose responsibility was to decide what should be printed on the printing press in the first place. That accident—through an enormous number of subsequent kinds of media, films, and magazines, books, and television, and radio—someone had to figure out how to manage the risk of "What should we broadcast today? What should we show in our movie theater? What should go in this month's magazine?" meant that that "publisher decides" model stayed true for 500 years.

It was a basic fact of the public media environment that you have to have someone willing to bear the risk. And the minute you had a medium where you don't have to spend a lot of money up front in order to have a public voice, a medium like we have today, that accident gets undone. Doesn't matter that half a millennium of cultural practice is built up around it.

I think that there's a kind of a glum realization that the accident of the economics of media made the publishers' control of what got said in public, that that accident is done now, and that the competitive landscape doesn't include silence on the part of amateurs.

[ON SCREEN: An image of Clay Shirky's article titled "Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable," and a quote from the article that says:

The old difficulties and costs of printing forced everyone doing it into a similar set of organizational models: it was this similarity that made us regard Daily Racing Form and L'Osservatore Romano as being in the same business. That the relationship between advertisers, publishers, and journalists has been ratified by a century of cultural practice doesn't make is any less accidental.]

And it will never include silence on the part of amateurs again. And the technical change to do that was quite trivial. The cultural ramifications of that change, they were huge because the media landscape we had in the 20th century literally cannot stand the shock of inclusion we're currently living through where all of a sudden everybody's got a public voice. And we're seeing the social effects of that accident ending.

NARRATOR: Read and watch more from Clay Shirky at btnn.tv.

The Transition to Mass Media

Video 2.2 provides a timeline of communication technologies:

This video is all on-screen text giving the date, place, inventor, and invention with images of the inventor and/or the invention.

2900 BC—Ancient Egypt: the first standardized written language (image on screen is of hieroglyphics).

776 BC—Athens: the first recorded use of homing pigeons to send messages

14 AD—Rome: the first postal service established

100—China: the invention of paper as we know it today

1455—Germany: Johannes Gutenberg invents the first printing press

1717—England: Henry Mill patents the first typewriter

1793—France: Claude Chappe invented the first visual semaphore

1821—England: Charles Wheatstone invented the telegraph and the microphone

1825—France: Nicéphone Niépce achieves the first photographic image

1831—U.S.A. (New York): Joseph Henry invents the first electric telegraph

1835—Samuel Morse invents Morse code

1876—U.S.A. (Boston): Alexander Graham Bell patents the first telephone

1878—England: Eadweard Muybridge produces the first motion picture

1877—U.S.A. (Connecticut): Tivadar Puskás invents the first telephone exchange

1887—U.S.A. (Washington D.C.): Emile Berliner invents the gramophone (recordable media)

1899—Denmark: Valdemar Poulsen invents the first magnetic storage medium

As discussed in the textbook, different types of media are associated with different economies. In pre-agricultural societies, people tended to be nomadic hunter-gatherers without permanent dwellings. There was little use for writing because it would have been difficult to carry books or scrolls while constantly on the move. Instead, the emphasis was on oral culture. The collective history and myths of the culture were told in songs and long epic poems that could be committed to memory.

Agricultural societies developed writing to keep track of inventories and business sales. Very few people could read or write. Those that were literate typically held positions of power advising religious and political leaders. The ability to read and write conferred access to knowledge, and knowledge equaled power. Those with knowledge often try to restrict access to that knowledge in order to maintain power. For example, in many cultures, women were discouraged from attending or not allowed to attend school. This gave men in those societies more power than women.

The birth of modern mass media can be traced to the development of industrial society. Here again we see how external technological, social, and economic developments influenced the shape of media. The invention of the steam engine radically altered how goods were produced. Instead of an artisan making products by hand with a few apprentices in a small shop, factories were built requiring dozens or hundreds of workers to operate the machinery. The need for many workers led to rapid growth of cities. At the same time, farming techniques were also rapidly improving, so fewer workers were needed for agriculture. With fewer jobs on the farm and more jobs in the city, workers began to move from rural areas to urban areas.

The result was a large concentration of people living in cities to work in all the factories. As technology made production more efficient, businesses suddenly found themselves with warehouses full of new mass-produced products. Goods were being produced faster than they could be sold. The solution was to increase demand so that people would buy more products. Companies began to spend more money on advertising to stimulate demand for their products.

At the same time, advances in printing technology made newspapers cheaper to produce than ever before. It was also cheaper to distribute newspapers in an urban area with high population density than in a rural area with very low population density. The cheap cost of newspapers led to increased literacy so that more people began to read newspapers. As the audience for newspapers increased, more and more advertisers began to use newspapers to market their goods. The increase in advertising revenue helped keep the price low, leading to further increases in circulation.

Newspapers began to compete for the largest audience so they would be more attractive to advertisers. This push led newspapers to emphasize objectivity in their news reporting in order to attract a wider audience. In the 1700s and early 1800s, most newspapers were overtly political and aligned with a political party. But in the late 1800s, newspapers realized that if they tried to be neutral and objective, they could attract readers from all the political parties and thereby increase circulation. This attempt to attract a mass audience evolved into the mass media system we know today.

Now, as the internet and cable television allow for an infinite range of choices, we see a movement away from mass media toward personal, customizable media. Pandora creates a custom radio station for each listener, and Facebook and Google can create custom news feeds for each user.

Information Society

An information society is defined as one where the number of workers involved in information processing is greater than those involved in agriculture or manufacturing. For example, today many jobs involve using a computer. This shift has increased the importance of a college education for career advancement. Additionally, new communication technologies can make work easier, but it does not always result in less work. Many years ago, a manager might have written a report in long-hand and given it to an assistant to type, and a different specialist might have created a visual presentation. Today, that manager is expected to use computer software to type and format the report and to create the visual presentation without the assistance of a graphic design specialist.

Figure 2.2. Workers Involved in Information Processing.

Watch Video 2.3 for reflections on the nature of information:

By Michael Wesch, Kansas State University

This video has music playing in the background and all the information is given by words on the screen.

A typewriter is shown, and the words "Characteristics of information:" are typed. Under that is this list:

- It is a thing.

- It has a logical place.

- Where it can be found.

SCENE: Camera goes through a library and shows a book with this title: On a Shelf. And the book's labels says, "In a file system." The camera moves to focus on a card catalog drawer, and the on-screen text says, "add a category." "Categories are managed." "It requires experts, and it is still hard to find."

Camera moves through the library to a file and shows the title on an envelope with microfiche in it: Issue of Newsweek - 125 No.9. The microfiche is put in a machine for viewing, and the magazine title is "TechnoMania" and the subtitle is "The Future Isn't What You Think." And the date of the magazine is February 27, 1995. The next headline shown reads, "The Internet? Bah!" The subtitle is "Hype Alert: Why Cyberspace Isn’t and Never Will Be, Nirvana."

A paper is shown with this text typed on it:

Characteristics of Information

- It is a thing.

- It has a logical place.

- Where it can be found.

- on a shelf

- in a file system

- in a category

- Managing information

- is managing categories

- It requires experts.

- and it is still hard to find

That same paper becomes a page with text-editing options, and the section called Characteristics of Information is renamed "assumptions about information on paper."

That page is highlighted and deleted.

New text is typed that says, "Digital information is different. It takes different forms. Digital information has no fixed forms, so we can rethink information beyond material constraints. So we must rethink information."

Google's search bar is shown, and the text inside the search bar is "the first website."

A new web page appears. The title is World Wide Web, with the question "What's out there?" as a link, which goes to a page where the text says, "There is no 'top' to the World Wide Web. You can look at it from many points of view. If you have to use a 'top' node, we recommend either this node or the subject list."

"Early websites built on familiar assumptions about information...as a thing with a logical place on a shelf, in a file system, in a category..." [shots of a Yahoo web page with categories and a list of links.] "Look what's happened here. Yahoo, faced with the possibility that they could organize things with no physical constraints, added the shelf back."

"Since then the web has been challenging our most basic assumptions...We learned that we might not need complex hierarchies to find information...9,120,000,000 indexed web pages times 551 words per page times 10 to the power of 12 equals over 5 trillion words, keywords. Almost 500 billion links. There is no shelf. The links alone are enough. Five trillion words...and we are just getting started..."

"Together we create more information than the experts...Wikipedia: 1740 million words in 7.5 million articles. The English Wikipedia alone has over 609 million words—roughly fifteen times as many as the next largest encyclopedia, Encyclopedia Britannica—and more contributors (282,875)." [Shows someone editing the page and that number going up to 282,876.]

"And we organize the information ourselves by adding tags and using keywords, and we organize without material constraints...3 tags and now it is stored in all 3 places at once, without folders, without restricted categories, without closed categories, without limiting categories, without miscellaneous categories, everything is miscellaneous."

"Such features are not just cool tricks. They change the basic rules of order. We no longer just find information...it can find us. We can make it find us. Together, we can make it find us." [shots of YouTube's search features and Google search] "It's an information explosion. It's an information revolution. And the responsibility to harness, create, critique, organize, and understand is on us—on all of us. Are we ready?"

Reflection Questions

Why do many positions now depend on the use of a computer? How have changes in technology altered the type of career you hope to have?

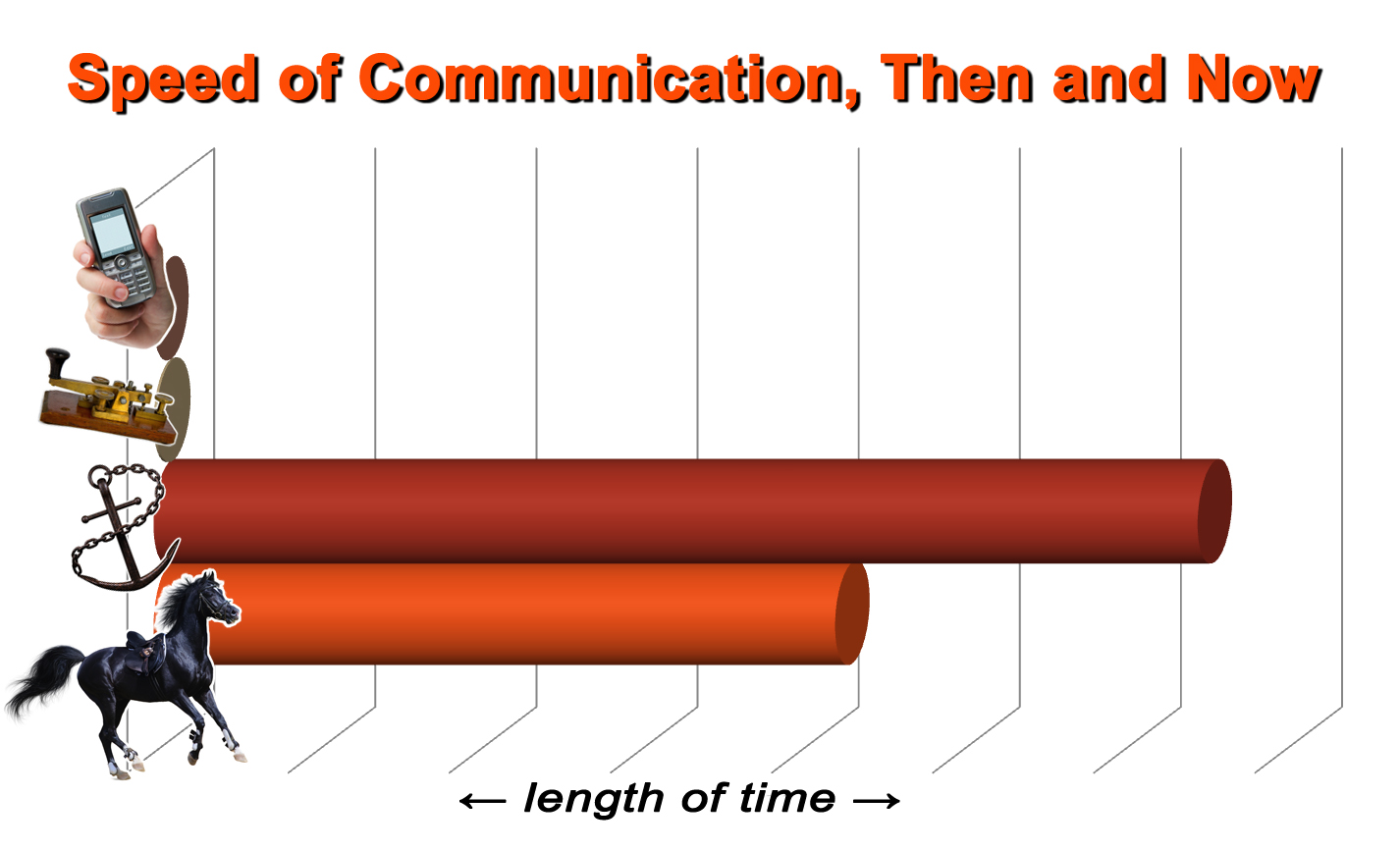

Communication Yesterday and Today

For most of human history, face-to-face was the only type of communication that took place. The invention of writing allowed information to be stored for later consumption without having to commit it to memory. This invention dramatically increased accuracy and allowed for increasingly complex thought. But for almost all of human history, the speed of communication was very slow. Simple information could be communicated over long distances by playing loud drums or using smoke and fire as signaling devices. Carrier pigeons could also be used to send short messages over long distances faster than a person could travel. But when sending long, complex messages, the speed of information was still limited to the speed at which a person could travel. The famous Pony Express took 10 days to travel 2,000 miles across the United States. Similarly, in the mid-1800s, it took ships 10–14 days to cross the Atlantic from the United States to Europe. If you sent a letter to Europe, you would have to wait a month or more before you received a reply! The telegraph was invented in the 1830s, and the first commercial telegraph line in the United States was established between Baltimore and Washington, DC, in 1844. Suddenly, information could be sent instantaneously! Today, we grow impatient when someone does not reply to our text message or email right away. The next time you get frustrated, just think of what life was like before electronic communication!

For most of human history, face-to-face was the only type of communication that took place. The invention of writing allowed information to be stored for later consumption without having to commit it to memory. This invention dramatically increased accuracy and allowed for increasingly complex thought. But for almost all of human history, the speed of communication was very slow. Simple information could be communicated over long distances by playing loud drums or using smoke and fire as signaling devices. Carrier pigeons could also be used to send short messages over long distances faster than a person could travel. But when sending long, complex messages, the speed of information was still limited to the speed at which a person could travel. The famous Pony Express took 10 days to travel 2,000 miles across the United States. Similarly, in the mid-1800s, it took ships 10–14 days to cross the Atlantic from the United States to Europe. If you sent a letter to Europe, you would have to wait a month or more before you received a reply! The telegraph was invented in the 1830s, and the first commercial telegraph line in the United States was established between Baltimore and Washington, DC, in 1844. Suddenly, information could be sent instantaneously! Today, we grow impatient when someone does not reply to our text message or email right away. The next time you get frustrated, just think of what life was like before electronic communication!

|

Mode |

Speed |

Distance |

|---|---|---|

|

Voice/drums |

1,000 feet per second |

Depends on atmospheric conditions and volume. Usually less than 30 miles. |

|

Smoke/fire |

Speed of light |

Depends on atmospheric conditions and height. Usually less than 30 miles. Can only send very simple messages. |

|

Carrier pigeon |

50 mph |

500 miles in 10–12 hours. Can only carry 3 ounces. |

|

Horse/Pony Express |

10–15 mph |

Missouri to California in about 10 days |

|

Railroad—late 1800s |

50 mph |

New York to California in 7–10 days |

|

Sailing ship—1700s |

10 mph |

North America to Europe in 6–8 weeks |

|

Steamship—late 1800s |

15–25 mph |

North America to Europe in 10–14 days |

|

Telephone/telegraph wire |

2/3 speed of light |

Anywhere on earth in less than 1 second |

|

Radio waves |

Speed of light |

Anywhere on earth in less than one second |

Video 2.4 shows an example of signal fire communication from Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.

Reflection Questions

How is this newer, faster, smaller, cheaper technology a positive thing for mass media? How does it hurt mass media? Is it always an improvement in daily life? Are there times when these technological developments may hinder society's growth?

We now live in a 24/7 media environment where major world events like wars and natural disasters are reported instantly. The 20th century saw the rise and maturation of mass media, where content producers focused on reaching the largest possible audience. As we move into the 21st century, we see content producers using newer digital technologies to create customized content for individuals. The average household today can choose from an almost unlimited number of television and film choices from multiple streaming services and cable channels compared to choosing among 4–5 broadcast stations in the 1970s. Spotify and Pandora have become major sources of music distribution, and each provides customizable stations and playlists. Meanwhile, cable news has to find content to fill up 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. Many observers feel much of this airtime is filled with speculation and uninformed opinion that harms democracy rather than helping it. The instantaneous nature of electronic media creates pressure to provide instant answers that are often wrong. Perhaps we would be better served if the media resisted that pressure and allowed for more thoughtful reflection.

The Rise of Web 2.0 and New Communication Networks

Another fundamental shift, often referred to as Web 2.0 signaled the rise of user-generated content. In the 20th century, a few large companies produced most of the content we consume. Today, YouTube videos, blogs, Facebook, and Twitter allow all of us to be content creators. Instead of only choosing among dozens of video channels or hundreds of newspapers, we can now select among an almost infinite variety of content.

The change is not just in the content we consume for entertainment and news (mass media) but also in our interpersonal communication. A hundred and fifty years ago, the only way to talk to someone was face-to-face or by sending a letter. Even as recently as 30 years ago, the only improvement was the ability to use a landline telephone—and making long distance calls was very expensive. Today, we can send instant messages and video chat with one or dozens of friends around the world simultaneously, and the cost is practically zero! This change makes it much easier for us to keep in touch with old friends and make new friends.

Another area that has changed is commerce. Record stores and video stores have all but disappeared and even bookstores are struggling to survive. Even nonmedia businesses have changed. Few people use a travel agent since we can now shop for airline flights, hotels, clothing, cars, and everything else imaginable online.

Just as important as the changes described above is the fact that we continue to increase the amount of time we spend using telecommunications. We now spend more time using media than just about anything else we do. We use it so much that it is hard to recognize how pervasive it is.

Watch Video 2.5 for a reflection on how Web 2.0 has changed communication:

[MUSIC - DEUS, "THERE'S NOTHING IMPOSSIBLE"]

(The following is a description of the actions occurring in the video.)

A close-up of a hand writing these words with a pencil: "Text is linear." "Uni" is added to the word linear. A caret mark is placed in between is and unilinear, and the words "said to be" are inserted. The word "often" is added before "said to be." The sentence now reads, "Text is often said to be unilinear." The words "often said to be" are erased and replaced with "when written on paper," so that the sentence reads, "Text is unilinear when written on paper."

In the next shot, a cursor appears and this sentence is typed on the screen: "Digital text is different." The sentence is edited multiple times. "Digital text is flexible, moveable, is above all...hyper." As these items are being typed out, they are also showing what the words are describing. For instance, "hypertext can link" is the next sentence that appears, and it shows the word link as an actual link. When the link is clicked on, it shows that links can take you anywhere.

The video transitions to a shot of the website WayBackMachine. "http://Yahoo.com" is in the search bar. When the cursor clicks on the button "Take Me Back," a list of dates appear with all the pages that existed during each year. A link from October 1996, is clicked on. The cursor right-clicks on the screen and selects "View Source" from the drop-down menu. The source code for the website appears. The following text is typed into the code: "Most early websites were written in HTML. HTML was designed to define the structure of a web document. <p> is a structural element referring to 'paragraph.' <Li> is a structural element referent to a 'list item.' As HTML expanded, more elements were added, including stylistic elements like <b> for bold and <i> for italics. Such elements defined how content would be formatted. In other words form and content became inseparable in HTML."

All the text is then highlighted in the code and deleted. The following sentences are typed: "Digital text can do better. Form and content can be separated."

An example of XML is displayed. Text is typed into the code: "XML is designed to do just that. <title> does not define the form. It defines the content. Same with <link> and <description> and virtually all other elements in this document. They describe the content, not the form. So the data can be exported, free of formatting constraints."

The video transitions into a shot of Google.com with the following typed into the search bar: "With form separated from content, users did not need to know complicated code to upload content to the Web."

The cursor clicks on the I'm Feeling Lucky button. This opens the blogger website. It shows how quick and simple it is to create a blog. A shot from News.com is shown, and this sentence is in bold: "There's a blog born every half second." The Google search bar is brought up again and the words "and it's not just text..." are typed into the text box. When search is clicked on a series of shots from YouTube, Flickr and other websites appear.

Google.com is brought up again. "XML facilitates automated data exchange" is typed into the search bar. That is erased and replaced with "two sites can 'mash' data together." Again, this is erased and replaced with "Flickr maps." Then the "I'm Feeling Lucky" button is clicked on. A shot of Flickr maps is shown. This question is brought up: "Who will organize all this data?" A series of shots that show the tagging action on various websites. The answer to the question appears: "We will. You will."

Google.com is brought up. In the search bar "XML + U & Me create a database-backed web" is typed.

An article is shown: "We are the Web." Various parts of sentences are highlighted throughout the article forming these sentences: "When we post and then tag pictures, we are teaching the Machine. Each time we forge a link, we teach it an idea. Think of the 100 billion times per day humans click on a web page. Teaching the Machine."

"The machine is using us. The machine is us."

The following text is typed onto a white screen: "Digital text is no longer just linking information... The Web is linking people, Web 2.0 is linking people...people sharing, trading, and collaborating." The video transitions to a shot of editing a Wikipedia page. All the content is removed, and the following is typed on the page: "We'll need to rethink a few things, such as copyright, authorship, identity, ethics, privacy, etc."

Lesson 2 Wrap-Up and Looking Ahead

Summary

By the end of this lesson, you should have learned (a) the evolution of media in agricultural and industrial societies and how it has influenced civilizations and changed the way we live, and (b) the famous SMCR model of the communication process.

Check and Double-Check

Before progressing to the next lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Looking Ahead

Lesson 3 presents the technological considerations of telecommunications, beginning with the radio spectrum and concluding with digital technologies.