COMM409:

Lesson 3: Journalism's Obligations to the Public it Serves

Lesson 3 Overview

Introduction

In the first lesson, we introduced the idea of using a balance scale to help resolve ethical dilemmas in a manner that allows us to maximize truth telling while also trying to minimize harm. We said the two pans of the scale would be labeled "Publish" and "Don’t Publish." We would attempt to identify the journalistic principles and factors particular to the news event itself that should be placed in the respective pans, all the while recognizing our obligations to stakeholders (those affected by the decision) involved in the story.

Furthermore, we would try to project the outcome of potential courses of action and identify alternatives that would allow us to move beyond gut-level or yes/no decisions. We’ll try to further this concept with a few concrete illustrations.

In Lesson 3, we need to also identify the various “roles” a journalist might be expected to play in today’s society and talk about how those moral obligations could influence the ethical decisions made in the pursuit of a news story. We’ll explore the journalist’s obligations as a

- citizen,

- watchdog,

- truth teller,

- empowerer, and

- participant or helper.

Finally, we’ll examine the love/hate relationship between the public and the media, with an eye toward increasing transparency.

Objectives

Here are the objectives for this lesson:

- Continue to develop a framework for resolving ethical dilemmas, including an understanding of the conflicting "roles" or obligations for a journalist.

- Explore the correlation between ethical transgressions by journalists and the public's perception of the news media.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, be sure you have completed the readings and activities listed in the Lesson 3 course schedule.

Please direct technical questions to the IT Service Desk.

Using the Scale

When confronted with an ethical dilemma, journalists will often draw on their years of experience and ask the question, “What do we normally do?” Although a good starting point, relying solely on that question has its drawbacks. For starters, every news story is unique and carries circumstances that can tip the balance scale in an unexpected direction. Perhaps a better starting point would be this trio of questions:

- What do I know?

- What don’t I know?

- What do I need to know before I can make a decision?

(Images courtesy of Thinkstock©).

For our scale analogy to work, picture yourself as a reporter working for a major metropolitan daily newspaper in New England. You receive a tip that a man from a town within your circulation area had sexual relations with a 12-year-old girl. (The girl is not a family member, so we are not talking about incest.) Being the diligent reporter, you check out the tip, talking to law enforcement authorities. They tell you that, yes, they have investigated this situation, but no legal charges were filed—nor will any be filed.

Based solely on that amount of information, would you publish a story?

If we follow the dictum of “What do we normally do?” the answer would have to be no.

Normally, when journalists investigate a tip and learn that no charges have been filed, they don’t write a story. For one thing, absent formal charges, journalists lack any of the supporting documents that provide legal privilege to help support the story.

But there’s more to this case than initially meets the eye:

- These “sexual relations” were not an isolated incident, but part of pattern that encompassed an 18-month affair with the family babysitter.

- The “man” happens to be running for a seat in the U.S. Senate against two other candidates.

- The man is campaigning on a platform of family values.

- The election is about a week away.

- Members of both political parties in the state where the incident occurred tell you—on the record—the claims are true.

- You learn the only reason charges were not filed is because the family wanted to spare the girl, who’d undergone counseling, the ordeal of a trial.

- Had charges been filed, they would have included statutory rape, a felony.

Sounds like we’ve identified some significant factors that would tip the scale in favor of publish. But hold the phone; you need to know a few more things about the case:

- The relationship between the candidate and the young girl happened several years ago and in another state.

- At the time of the encounter, the man was not an elected official, nor seeking office.

- When you confront the candidate, he denies the allegations and claims the girl was “crazy” and “in a mental institution” when she originally accused him.

- The campaign staff of one of the man’s opponents appears to be behind the original tip.

- Publishing the babysitter sex story, especially so close to the election, could distract voters from some of the important issues facing the state.

- Publication of the story could also force the young girl to revisit this painful period in her life.

Are those factors enough to tip the scale to don’t publish?

Do some of those factors have a greater weight than others? What about the stakeholders—not just the girl and the candidates, but the voters? And what about the journalist’s moral obligations?

Our case study grew out of the 1996 Republican primary for a U.S. Senate seat in Maine. The man accused of sexual relations with the young girl was W. John Hathaway, a wealthy businessman who’d recently moved to Maine from Alabama. The candidate accused of planting the story was Robert Monks. The third Republican candidate, who stayed out of the mudslinging, was Susan Collins. Collins went on to win the Republican primary and the general election and remains a U.S. senator to this day.

The news organization facing the ethical dilemma was The Boston Globe, then a major player in the coverage of politics throughout New England. Upon receiving the tip about Hathaway, the Globe sent a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter to Alabama to investigate the claims. Convinced they were true, and believing publication would serve the public interest by providing information Maine voters needed to know, the newspaper printed the story.

But, as you know, this case study is not an isolated incident. Politicians accused of being involved in sex scandals have become more frequent in the age of the internet. As you can see from the other examples below, following the story to the end before deciding whether or not to publish is very important (source credit: NBC and The Washington Post).

| Truth Meter | Details |

|---|---|

|

True |

Politician: Dennis Hastert Synopsis: 2015 — Allegations of payoffs are what first brought this scandal to the public’s attention. Investigation: As the situation played out over months of investigation, it was revealed that the payoffs were to silence a boy on a team Hastert had coached decades earlier. A second person came forward as well to say Hastert had allegedly abuse her brother. Resolution: He pled guilty to paying the hush money but not the alleged sexual abuse. Outcome: Finally, at his sentencing, Hastert admitted to abusing the players on his teams, paying them to keep them quiet and was sentenced to 15 months in prison for the hush money payments. This sentence did not include penalties for the sexual abuse itself because the statute of limitations had run out |

|

Uncertain

|

Politician: Ted Cruz Synopsis: 2016 — Cruz is currently facing accusations that he has had at least five extramarital affairs. Investigation: Cruz has denied the allegations and accused Donald Trump of planting the story which was published in The National Enquirer. The story is still ongoing and two of the women he allegedly had an affair with have been identified. Both have denied the accusations. It is also part of the investigation to question The Enquirer’s ethics and credibility. Resolution: There has been no resolution yet. It is still unclear is any or all of the allegations are true. Outcome: This case is a perfect one for us to consider for this course because we don’t have the benefit of hindsight. As of now, we do not know if Cruz had any affairs. So ask yourself—what would you do if you were a reporter, editor or news director? |

A Journalist's Obligations

The author of our text opens Chapter 4 with the notion that journalists sometimes find that their journalistic duties conflict with their moral obligations. Yes, it’s true that journalists are often forced to “wear many hats”—and not just because they are frequently called upon to produce multimedia versions of the stories they’re trying to tell!

In the introduction, we mentioned six distinct roles or societal expectations the journalist might be called upon to meet.

- Citizen: Just like everyone else in society, the journalist would be expected to obey the law.

- Committed observer: All reporters are observers, it's part of their job so there's an element of it in every story. When we say committed reporter, though, we are referring to the reporter staying with a story and observing what happens when there's really tough or disturbing stuff going on. As committed observers, journalists stay with it and keep reporting back to the public.

- Watchdog: Hold the powerful accountable.

- Truth teller: Building on the roles of observer and watchdog, the role of truth teller means serving the informational needs of the public, telling the story regardless of the consequences.

- Empowerer: Staying on the story and helping the people solve the problem is how the empowerer role works. It's beyond normal reporting because there is a *call to action* to the public to get involved or make changes.

- Participant or helper: This is when journalists get involved with a story in the hope of making things better. This is an active stance, they are doing something to intervene.

Although these roles are somewhat neatly defined it is easy to see that there is overlap between some and that conflicts can arise for journalists when they try to live up to all of the expectations at the same time. These conflicts arise from the coverage of all kinds of stories: from sports to politics or entertainment to business. Let’s turn to the police beat as a way to illustrate the potential for conflicting moral and journalistic obligations.

Case Study

Your community has been hit by a major tornado which has devasted large parts of the town.

| Citizen |

While capturing video footage, you inadvertently record a man breaking into a damaged home and carrying out a TV. As a citizen, you are obliged to follow the same laws as everyone else. There's no law about witnessing crimes, but normal citizens might feel obligated to report them. Should you alert the police and/or give them your footage? |

| Committed observer |

As a committed observer, you stay with the story beyond the initial fact-based reporting. You your obligation would be to look for the angles of the story that the citizens need to know. Perhaps it is beyond just the illegality of drug dealing and might also include stories about who is buying the heroin, where the transactions occur, and what signs people should look for if they are worried about a loved one. |

| Watchdog | Who are the people in power you might look to hold accountable? Did the warning sirens go off? Are the police doing an adequate job of protecting the homes and busineses that were damaged? |

| Empowerer | As an empowerer, you would strive to inform the public about how they can take action. What donations are needed? Where do people go if they need help? |

| Truth teller | As a “truth teller,” you would simply write the story—the who, what, where, when, why about the tornado and its aftermath. |

| Helper or participant | As a “helper or participant,” you might work at a shelter passing out blankets so you can see and talk to the people most affected. You might donate blood as part of a story about a blood shortage. But what if by trying to help, you’re viewed as changing reality and your news organization’s reputation suffers? Or, by intervening, you change the nature of the news itself? |

Getting Involved with the Story

Many of these conflicts hinge on the question of whether journalists are simply observers or whether it’s OK for them to become participants in stories they cover. As a general rule, intervention by a journalist is discouraged for two reasons:

- It can change the nature of the event, rendering it no longer authentic.

- It can lead the audience to perceive bias on the part of the journalist.

Notice we are not saying a journalist should never intervene. When there is a clear, imminent danger (perhaps even the threat of death) and no one else is available, we can agree that intervention is warranted. Ditto if the journalist possesses special skills the situation requires.

Before acting, however, journalists should make sure they are not manufacturing the “danger” or getting involved simply to advance their own self-interests. Intervention can create the risk of backlash. Or, even worse, a journalist’s participation could prevent qualified individuals from providing needed assistance and possibly jeopardize others.

Case Study

Be sure you have read the case study in the textbook called For Journalists, a Clash of Moral Duties: Responsibilities as professionals and as human beings can conflict.

Let’s use two examples to explore the question of intervention.

Journalist Wolfgang Bauer and photojournalist Stanislav Krupaf were undercover for two months travelling with Syrian refugees in 2015. Their cover story was that they were English teachers and they faced the same events experienced by the Syrians they were travelling with, including being arrested twice, being kidnapped, and being thrown overboard from a ship taken over by smugglers.

Their journey is chronicled in a book, Crossing the Sea: With Syrians on the Exodus to Europe, and they serve as an excellent example of fly-on-the-wall reporting.

They were there observing (and experiencing first-hand) the hardships and abuses the Syrians suffered. Unlike Nazario and Williams, Bauer and Krupaf did not intervene even when they might have. Instead, the journalists chose to place the spotlight on ordinary individuals because they believe them to be part of a newsworthy topic. They simply let life unfold and recorded what happened. Newsweek did an interesting profile of the two journalists which includes some photos and additional stories.

Also in 2015, Egyptian journalist Magdy Samaan was also travelling with Syrian refugees. Unlike Bauer and Krupof, however, Samaan identified himself as a reporter. Though he also reported on what he saw and heard first-hand, Samaan did intervene during his 15-day journey. In several instances, he acted as a translator. In another, he gave a portable charger to a man who needed to charge his phone so he could contact his family.

Did these interventions change reality? Of course. If no one else was present who could translate, what would have happened? You can read Samaan’s entire story on The Telegraph.

While it’s natural to have an emotional reaction to those in need, journalists would do well to consider which accomplishes more:

- One reporter helping one individual at the scene of devastation, such as Hurricane Katrina?

- Or, one reporter telling the story of that devastation so that millions of other people become aware and step forward to help?

Public Perception of the Media

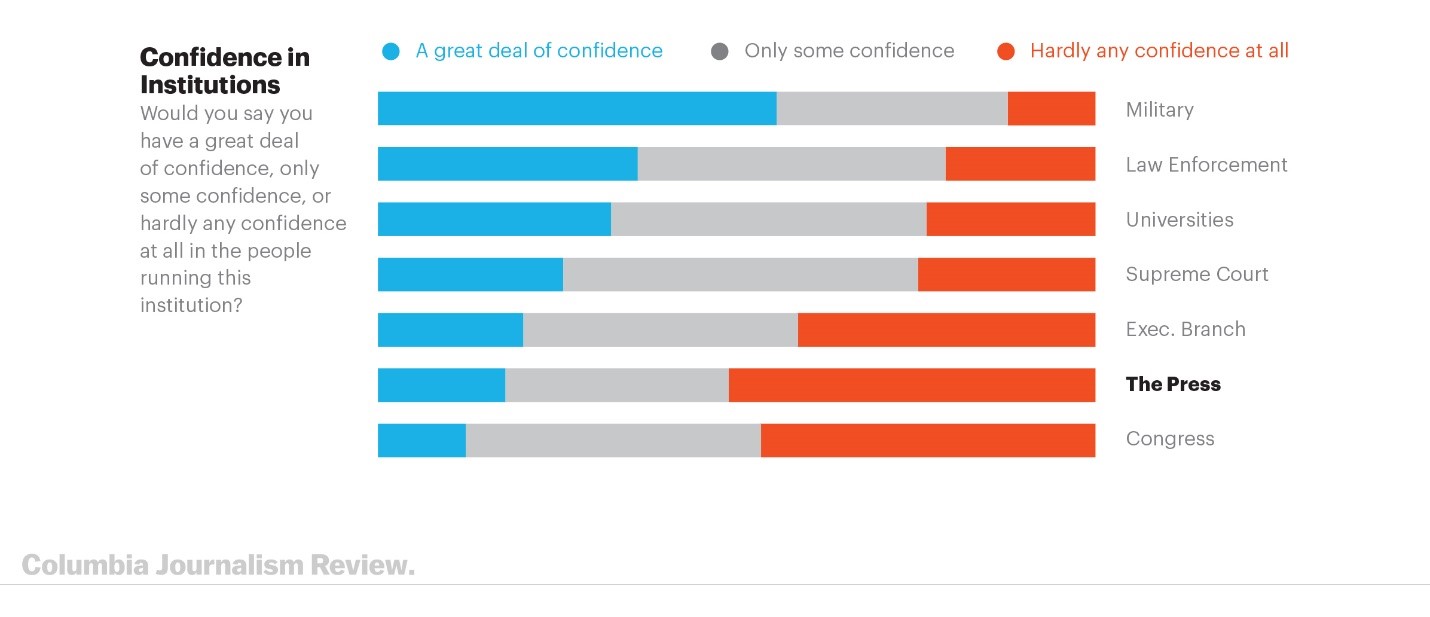

A 2019 poll by Columbia Journalism Review and Reuters found that Americans trust journalists as an institution less than they trust the military, law enforcement, universities, the Supreme Court and the Executive Branch. Of the institutions included in the survey, journalism was only trusted more than Congress. Ouch!

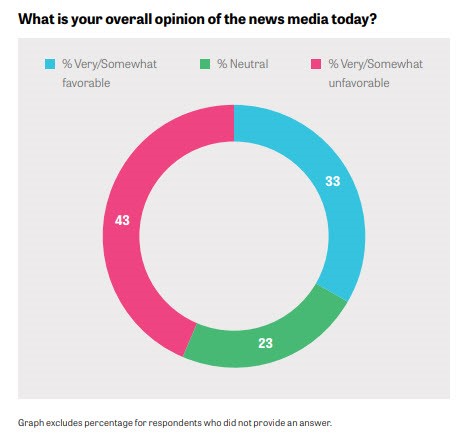

A 2018 poll conducted by The Knight Foundation found a similar negative perception: 33% of Americans have a somewhat or very favorable view on the press, 23% have a neutral view, and 43% have a somewhat or very unfavorable view of the press.

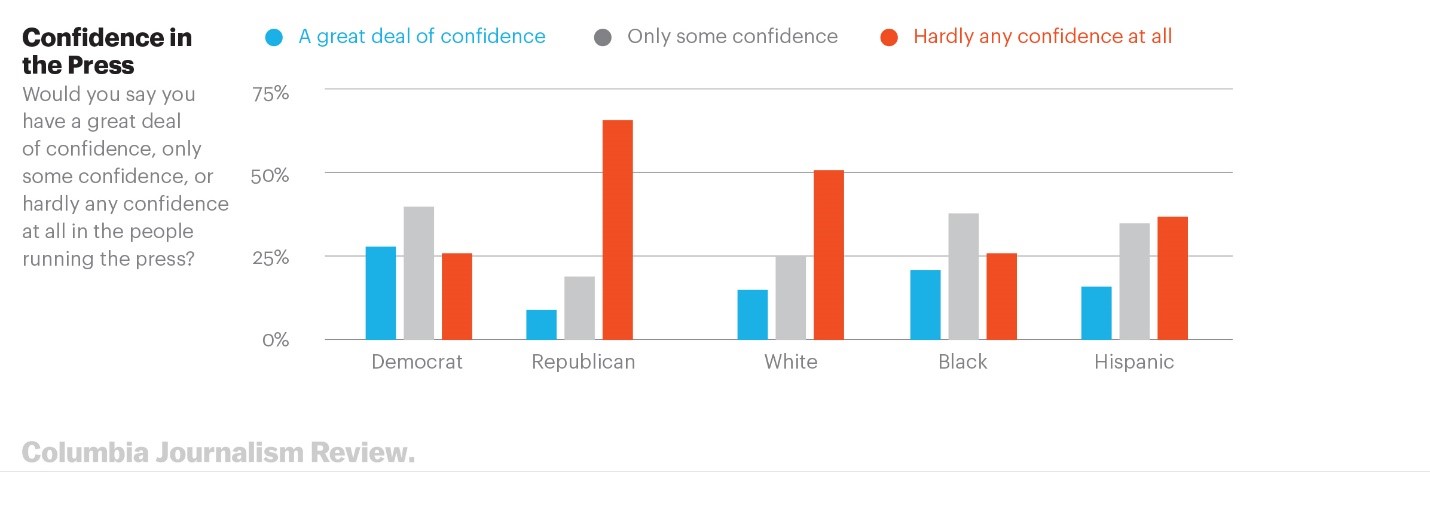

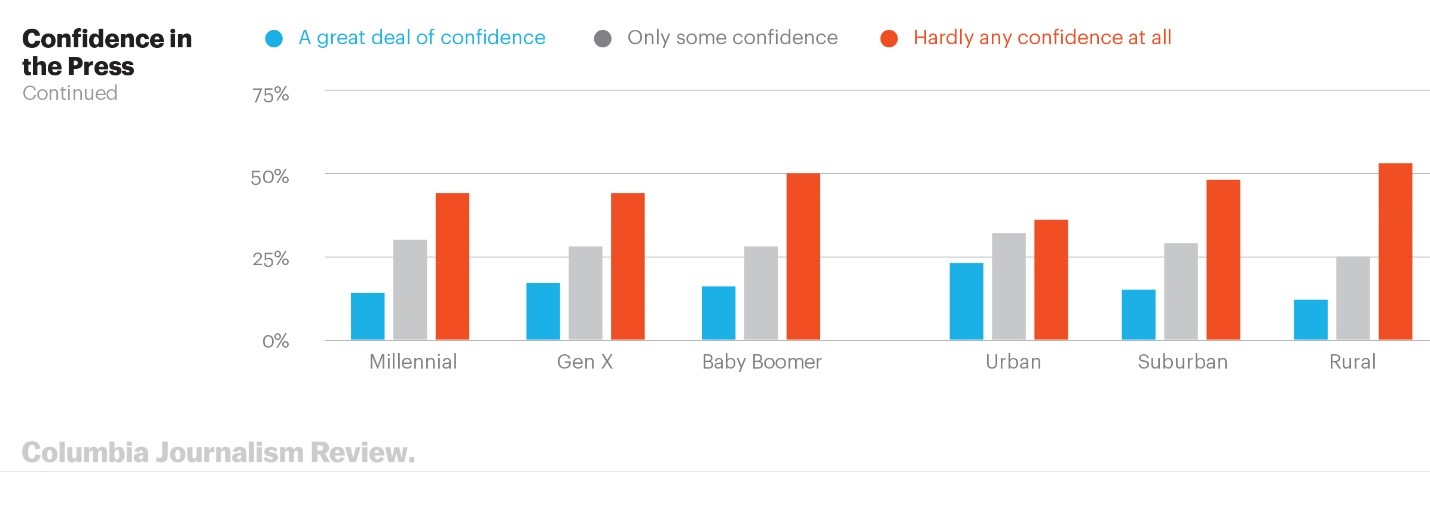

Breaking the Knight Foundation results down to look at specific demographics, we can see that older people, people of color and Democrats have a more favorable view of the media than younger people, Caucasians and Republicans or Independents.

| Demographic | Favorable | Neutral | Unfavorable |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 33% | 23% | 43% |

| 18–29 years old | 22% | 31% | 45% |

| 30–49 years old | 29% | 26% | 44% |

| 50–64 years old | 35% | 20% | 44% |

| 65+ years old | 43% | 15% | 39% |

| White | 28% | 20% | 51% |

| Black | 51% | 26% | 21% |

| Hispanic | 38% | 29% | 32% |

| Democrat | 54% | 26% | 18% |

| Independent | 25% | 25% | 48% |

| Republican | 15% | 16% | 68% |

A breakdown of the results from the CJR/Reuters poll show similar results reflecting political affiliation, race, and age.

As Nazario noted, the public doesn’t always understand the role of journalists in society and the industry hasn’t always done a good job of explaining itself. Newsroom leaders take a lot for granted about public understanding, so they share part of the blame.

- The public doesn’t always differentiate between fact-based reporting and opinion columns and blogs.

- While the public probably understands that it’s “news” when a plane crashes and not when it lands safely, such a definition leads to claims of always focusing on the negative.

- Journalists are sometimes viewed as “community spoilers” for pointing out problems. But how can those problems get fixed if reporters don’t focus attention on them?

The text offers a laundry list of the ways journalists invite public scorn. Some are real faults, others perceived. You can find suggestions to combat public misperceptions in the SPJ Code of Ethics under the heading of "Be Accountable."

Stakeholders

In Lesson 1, we mentioned the importance of identifying all of the stakeholders in an ethical dilemma. We said it was necessary to look beyond the obvious stakeholders who would be affected by the journalist’s decision and assign respective weights to all of them. Often, trying to resolve an ethical dilemma by simply making a decision that will please one stakeholder could end up harming other stakeholders.

Take a look at the following “Police Log” entry that was published in 1993 by the Penn State student-run publication The Daily Collegian. Here is the actual story, with one minor alteration:

![]()

Police Log

Couple cited for sex in stuck elevator: A man and a woman were charged with disorderly conduct Saturday night after police found them having sex in an elevator.

The State College Police Department was called to Park Hill Apartments, 478 E. Beaver Ave., because an elevator was stuck between floors.

When the doors were opened, a gust of hot wind was emitted and two people … (NAMES REMOVED BY THE COURSE AUTHOR) were found partially dressed having sexual intercourse. The officer reported the couple was practicing safe sex by using a condom.

The “sex in the elevator” item eventually became the focus of a chapter in a journalism ethics text by Steven Knowlton. The controversy arose over the Collegian’s decision to include the names of the two individuals cited; the woman mentioned in the story withdrew from the university before the end of the term and Knowlton’s text suggests the embarrassment following the publication of the story was responsible.

Suppose we decide to minimize harm for the woman and her partner and omit their names from the story, publishing all other details. Will that decision affect any other stakeholders?

- If we don’t name the couple, we now place every resident of Park Hill Apartments under the cloud of being the infamous “Sex in the Elevator Couple.” If you live in the building, how would you feel if your parents saw the story? Professors?

- If we don’t print their names, how do we respond to other individuals who were named elsewhere in that police log? And yes, the blotter did name two other individuals who were cited that weekend for disorderly conduct, including one individual cited nine times in five different places because of alcohol-related disturbances. Isn’t it “embarrassing” to those individuals who were also cited? Is it fair their names were published but not the couple?

As an aside: The full version of the police log containing the names of the sex in the elevator couple is no longer readily available online, raising the whole issue of “unpublishing” information documenting youthful indiscretions now that Internet searches are so easy. As an experiment, I typed the woman’s name into Google and got 8,000,000 hits; the Collegian story was not among the first five pages. I then typed her name and “Collegian” into Google and got 7,210 hits; the story was not among the first three pages. I didn’t keep searching beyond those initial eight Google pages!

Lesson 3 Wrap Up

Summary and A Final Thought

In defining journalism as “the independent act of gathering and disseminating information, in which the practitioner is dedicated to seeking the truth and owes first loyalty to the consumers of the information” we might be left to wonder if that leaves any room for journalists to be “human.”

In trying to address that question, consider the words of Rachel Smolkin, whose thoughts close out Chapter 4 of the text:

- “Your humanity—your ability to empathize with pain and suffering, and your desire to prevent it—… make you a better journalist.”

- “If you change an outcome through responsible and necessary intervention … so be it. Tell your bosses, and when it’s essential to the story, tell your readers and viewers, too.”

- “Remember, though, that your primary—and unique—role as a journalist is to bear witness.”

Check and Double Check

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 3 Course Schedule.

Looking Ahead

Next lesson, we will provide youy with a few more tools to incorporate intothe process of resolving an ethical dilemma, such as rule-based thinking and ends-based thinking.