COMM428A:

Lesson 2: Brands and Brand Equity

Lesson 2 Overview

Introduction

In this lesson, we will explore the fundamentals of branding and why companies of all sizes invest heavily in their brands. There are so many products and services competing for a consumer’s attention that it is essential for businesses to make branding a priority so that consumers have a favorable opinion and are able to differentiate the brand from that of the competition.

Branding goes beyond the name or logo and is a combination of many other factors, including packaging, product performance, and the consumer’s perception and knowledge with the brand. It’s essentially the sum of all contacts a consumer has with that particular brand, including that of the integrated marketing communications used by the company.

Objectives

Here are the objectives for this lesson:

- Describe the modern definitions of the brand

- Describe branding and its fundamentals.

- Discuss why branding matters in the marketplace.

- Explain how brands use a universal language to become more memorable and valuable to their customers.

- Discuss if truth is in advertising or in the general media that we consume each day.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Please direct technical questions to the IT Service Desk.

What Is Branding?

Branding is important for all sizes and types of businesses. This is especially important in today’s highly competitive marketplace. Brands that are able to successfully differentiate themselves from their competitors and create value for their customers will be the ones with an advantage.

Before we begin, let’s start with what a brand isn’t. It isn’t the company’s logo and it isn’t about making consumers aware of the company’s product or service. Those are indeed elements of a brand, but they aren’t the sole elements.

So, what exactly is a brand? Originally, the purpose of branding was to identify a product or service as belonging to a certain entity. A simple example would be the branding irons ranchers used to mark their cattle or the engraved signs that existed for thousands of years. Today’s definition goes much further. It has evolved to include everything an entity does with the intention of being recognized and only now incorporates many different kinds of intentional experiences. Interbrand’s Christensen and Hertioga (2018) provide this useful definition:

“A brand is the sum of all expressions by which an entity (person, organization, business unit, city, nation, etc.) intends to be recognized.”

Ultimately, brand is the perceptions that customers have of that entity and that is gained through all their experiences with that brand. Every single facet of an entity’s interaction with a consumer sends an implicit message that leads to a collective perception—positive or negative—of that entity.

Video 2.1, featuring Ann Rubin, Vice President of Corporate Marketing at IBM, helps place additional context around branding and how entities can build sustainable brands.

The definition points out what people would typically think of when they hear the word “brand”—a logo, a specific typeface, unique colors. These are the tangible manifestations of a brand, the things you can “reach out and touch.” But these descriptions also make it clear that brands also have important intangible aspects. They allow consumers to differentiate between brands for similar products (known as undifferentiated products). Brands also comprise the associations and images that pop into the minds of consumers when they are encountered.

This is a critical point—brands exist in psychological space, not physical space. Products exist on grocery store shelves; brands exist in people’s minds. This distinction becomes critically important when it comes to understanding brand equity, targeting, and positioning.

Products exist in physical space |

Brands exist in psychological space |

Because brands exist in psychological space, the most important aspect of their definition is also intangible. That is, the most important definition of a brand is not descriptive, but functional. What is most important about brands is not what they are but what they do. And from the standpoint of someone who is interested in a career in strategic communications, the key question is, “what function does a brand serve for strategic communications?”

In the book Advertising & The Business of Brands, the writers at The Copy Workshop (executive editor Bruce Bendinger [2009]) provide the following functional definition for brand.

“A brand is a conceptual entity that focuses the organization of marketing activities—usually with the purpose of building equities for that brand in the marketplace.”

This functional definition should make it clear that brands have important impacts not just on consumers but on strategic communicators. By developing and agreeing on a precise brand meaning, strategic communicators can clearly organize and implement strategic plans across the organization. This is more than choosing colors and typeface and tagline. It is defining what a brand should mean in the minds of consumers (the process is called positioning and will be covered in more depth in Lesson 4).

In this functional role, therefore, the brand serves the purpose of focusing all brand-related strategic communications across the organization. If everyone does not have the same understanding of what the brand means, it is very unlikely different elements of the campaign will be integrated. Clearly defining brand meaning facilitates the integration of marketing communications.

In their best-selling book on effective communication Made to Stick (which I highly recommend for anyone interested in a career in strategic communications), Chip and Dan Heath (2007) compare the integrative role of the brand to the idea of commander’s intent (CI). In the 1980s, The U.S. Army began to add a CI to the top of every order. The Army had discovered that complex plans would become obsolete as soon as circumstances in the field didn’t go as expected. And nothing ever goes as expected. The CI (brand) provides a clear, plain-language statement of the ultimate objective of the plan so that officers (strategic communicators) can respond to changes in the field (marketplace).

Heath and Heath (2007) paraphrase Colonel Tom Kolditz of West Point as comparing many plans to writing instructions for a friend to play a game of chess—a friend knows absolutely nothing about the game. As soon as the opponent makes an unexpected move, the plan is worthless. By adding a clear CI, the friend has enough of an understanding to let their instincts take over when the unexpected occurs.

Brand meanings guide the strategic communications efforts of organizations the same way CIs guide officers carrying out military orders. No matter how many unexpected changes are encountered in the marketplace, if communicators understand the brand, they will be able to rely on their instincts to make the best adjustments.

Finally, it should be noted that brand is an exceptionally broad and encompassing concept. Most casual observers think of consumables (things you buy, use up, and buy again) or of durable goods (things you buy but keep for several years or even decades) when they think of brands. But brands comprise anything that can be promoted. Rock bands are brands, as are movies, musicals, and plays. So are politicians. Even purely abstract ideas are brands. The Sierra Club, for example, is dedicated to promoting environmentalism, a purely abstract set of ideas and priorities about how we should interact with the natural world. They are not selling anything other than ideas and ideals.

As you can see, brands mean different things to different actors in the strategic communications process. In the next section, we will take a look at these actors and what brands mean to each.

In the journal article What Is a Brand?, Hertioga and Christensen (2018) help us understand the meaning of a brand and why it is important. They further illustrate the ingredients of successful branding and the implications:

- Clarity of thought: A solid definition helps clarify which of a company’s actions can be classified as branding and which can’t. Not everything a company does is branding.

- Clarity of speech: Avoid using brand when it doesn’t apply, as that creates more clarity for the brand.

- Clarity of method: Good branding should pay special attention to both the entity that created it as well as its stakeholders.

Actors in the Branding Process

Broadly speaking, there are four main sets of actors in the branding process:

- The marketer or advertiser

- The strategic communicator

- The media

- The audience

These should be thought of as separate roles, not necessarily separate organizations (with the exception of the audience, which is always a separate group from the marketer/advertiser, strategic communicator, and media).

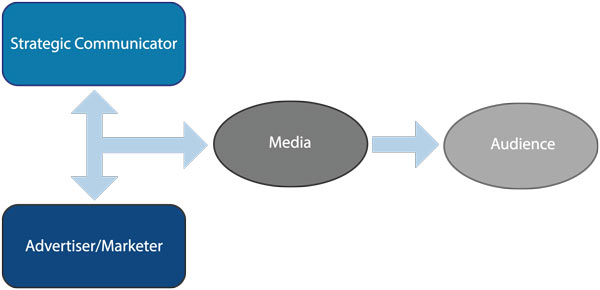

As the figure below implies, the strategic communicator works closely with the marketer/advertiser to develop the brand positioning (message) strategy. This is then transmitted via the media to the audience.

Figure 2.1. Strategic Communication Actors

Keep in mind that these boxes represent roles, not organizations. Therefore, the strategic communicator may work for the marketer/advertising (in the marketing, advertising, or public relations department).

The strategic communicator may also work for the media organization. Many small marketers (usually local but sometimes regional or national) do not have in-house or agency communications talent, and therefore may rely on the media for communications support. In these cases, the media takes on the role of agent as well as media sales. This arrangement is quite common for local newspaper and radio, when local clients need help developing advertising messages and materials. It is also common at the regional and national levels for companies in highly specialized (often B2B) industries. These marketers may be advertising in highly targeted national media (usually magazines) but not do enough advertising overall to justify maintaining in-house communications talent or an agency relationship.

In addition, the media company may be playing the role of marketer. That is, the media company may be marketing itself, either in terms of promoting itself to audiences as a source for content or promoting itself to marketers as a place to buy advertising.

Media companies promoting their content may promote themselves through channels they own or by buying advertising in other media. For example, Fox may promote an upcoming college or NFL football game during other Fox broadcasts or by buying digital advertising on USAToday.com. In either case, Fox is playing the role of a marketer, working with either in-house or agency communications talent to develop a message, and communicating that message through the media to audiences.

Media companies promote themselves to marketers as a place to advertise, called media marketing or advertising marketing. In this case, marketers become the audience. Advertising marketing is often done through direct selling but may also include advertising in trade publications, such as Advertising Age or Adweek (two publications I highly recommend for all advertising and strategic communications students).

As you can see, the basic actors in the strategic communications process are quite straightforward. However, the roles are flexible. Strategic communicators can work for marketers and media companies, the media can assume the role of marketer, and marketers can assume the role of audience.

Given these flexible roles, it can be further pointed out that the modern brand means different things to different actors in the marketing process:

- For marketers, brands are business units.

- As we will see in the section on organization structures for marketing, because brands are the “central organizing concept,” they are often organized as business units.

- For agencies, brands are clients.

- Strategic communicators are typically hired by marketers for long-term, working relationships. The term client is usually reserved for long-term customers with whom a firm has a close working relationship or partnership.

- Agencies also refer to brand clients as accounts.

- For the media, brands are customers.

- The term customer is usually used when a relationship is transactional in nature. For the media, advertisers order space, time, or placements, and may do so for several years. But because marketers don’t usually have the kind of in-depth working partnership with a media company that they do with an agency, they are more accurately seen as media customers.

- As noted above, when the media performs more of the role of strategic communication agent or adviser, it would become more of a client relationship.

- For consumers, brands are symbols.

- Ultimately, marketers and strategic communicators want to create meaning for their brand. And that meaning will be something more than just the manifest aspects of a brand (the colors, typeface, and tagline). That is when brands become something more. They become tangible symbols of something intangible.

When brands are successfully managed to be symbols for consumers, they create brand equity in the marketplace. This concept is explored further in the next section.

Brand Origins and Brand Equity

Origins of Modern Brands

The concept of branding can be traced to cattle ranching, when branding irons were used distinguish among herds. At the end of the 19th century, mass production and mass distribution of goods to mass-educated consumers in a society with growing mass media led to the necessity of product branding.

Harley Proctor is often credited with implementing the first brand when he burned a moon symbol on crates of soap as an identifier.

Early brands were identifiers, not as symbols of much more. But before long, mass-produced goods were found to be highly consistent in terms of quality. Therefore, brands began to become symbols of consistency and quality. Early brands were often nothing more than family names or place names, but they began to symbolize desirable abstract ideas.

|

|

Over time, marketers and strategic communicators discovered that successful brand messaging could turn icons and logos into symbols of much more. David Ogilvy (2010), a famous figure from advertising history, said of brand:

[Brand] image means personality. Products, like people, have personalities, and they can make or break them in the marketplace. The personality of a product is an amalgam of many things—its name, its packaging, its price, the style of its advertising, and above all, the nature of the product itself.

Today, brands can symbolize a whole host of abstract (usually human) qualities. Take a look at the following logos and think about the personalities of each.

|

|

|

In the following lessons, we will take a closer look at the techniques strategic communicators use to turn their brands into symbols and why. For now, the focus is on the fact that brands have come to symbolize abstract qualities and personalities in the minds of consumers. And when it comes to strategic communications, perception is reality. If people believe your brand is longer-lasting, then it is. If people believe your brand makes them more rugged, then it does.

If a large number of people have a positive belief in their minds about your brand, if your brand has become a symbol of something more, that is brand equity.

Measuring Brand Equity

The concept of brand equity is not that much different from the concept of home equity, although (as we will see) it is quite a bit more difficult to measure. If your home is worth more than you owe on the mortgage, you have equity. If your brand is worth more than what you’ve invested into it, you have brand equity.

Home equity is calculated by getting an estimate for the current value of your home and subtracting what you owe on the mortgage. Getting an estimate for the current value of a brand, however, is much more difficult. Unlike houses, brands are all different. In addition, as we’ve learned, brands are not lined up along a street for all to see, they are hidden in the minds of millions of consumers. But the difficulty of measuring brand equity has not stopped people from trying. In the end, there is another significant similarity between home equity and brand equity—you don’t really know what it is worth until it is sold.

One way to place a value on a branded product is to compare it to a nonbranded (generic) product. How much more profit from future sales does the branded product represent than a nonbranded product? That would be a measure of brand equity. However, we would have to convert all those future profits to present dollars to make them comparable. The present value (PV) of future earnings is simply a method to discount those future earnings to reflect the fact that a dollar now is worth more than a dollar sometime in the future.

As you can see from this basic equation, there are a lot of hypotheticals. There would have to be an otherwise completely similar generic product with which to compare the branded product. And the present values would be based on profit forecasts that are best guesses.

There is strong market demand for more sophisticated measures of brand equity (we are talking about a multibillion-dollar industry), and a number of market research and consulting companies have developed their own measures and metrics. Among the most recognized is from Interbrand.

I am sure you agree this is an impressive group of companies. CEOs think so too and are very eager to make the list. But how exactly does Interbrand measure brand equity?

Visit their site to review their approach. You can also watch a brief overview of Interbrand’s equity measurement methodology in Video 2.2.

As you can see, Interbrand’s approach has even more moving parts and assumptions than the basic brand versus nonbrand analysis introduced earlier. They examine brands across three broad areas of strength, financial performance, and role of brand to come up with a value.

The demand for brand valuation data is so strong that multiple respectable agencies now publish annual rankings of the world's most valuable brands—including Interbrand and Kantar. Because methodologies for each agency differ, the valuations will differ. According to Kantar, brand valuation is a combination of science and judgment, and that’s why valuations differ. Millward-Brown (now part of Kantar) places more emphasis on consumer opinion and loyalty than Interbrand, which appears to favor brands in more stable and proven industries. Both companies must make judgments about future earnings growth—sometimes it is very difficult to predict what the future will bring, even when that future is a few weeks out. In the case of Apple, our valuation indicates that not only are the company’s earnings increasing rapidly, so too is the brand contribution based on feedback from consumers around the world.

When basing estimates on so many moving parts, and when dealing with something as intangible as a brand, differences and swings in evaluations are to be expected. This is not to be critical or Interbrand, Kantar, or any other company’s brand equity valuations. They are doing an excellent job on a difficult topic. (They have also done an excellent job promoting the Interbrand brand.)

In their second installment on branding Why Invest in Branding?, Hertioga and Christensen (2021) explore why entities need to invest in branding, and how it creates economic value. They recognize that branding is everything an entity does with the intention of being recognized, and recognition binds trust and affinity.

Brand Organizational Structures

Arens and Weigold provide an overview of the most common organizational structures of marketers large and small. There is one small point of clarification, which amounts to a rather large point of difference.

The Brand Management System

In the modern marketplace, organizations with multiple product lines usually operate with a brand management system. Brand-managed companies include Procter & Gamble, Kellogg’s, Unilever, and Nestle. Because of the power of branding, these companies have found it more advantageous to create separate brand identities for each of their product lines. Each brand group, under the leadership of a brand manager, has autonomy to make all decisions about how to build equity for their brand in the marketplace. Under this structure, the centralized marketing department operates as a service provider to the brand managers (these groups are often called marketing services departments).

The brand management system was first successfully deployed at Procter & Gamble in the 1930s, as proposed and developed by Neil McElroy (who later became Secretary of Defense under President Eisenhower). The idea of brand management is to give each brand group the autonomy to operate more independently and flexibly in response to changing market conditions. Another central component is competition. Each brand manager must carve out a unique niche for their brand or compete with other brand managers with similar product groups—from the same company!

An additional benefit of the brand management system is that if one company brand is damaged, it does not spread to other company brands.

These brand managed systems are typically seen as decentralized organizations. Because there are multiple brand managers, they have a more horizontal structure, as opposed to the vertical, top-down centralized model.

Arens and Weigold classify companies with brand managers as "centralized”; in most cases, they are seen as decentralized. They go on to discuss decentralized structures, pointing out that in these organizations brand managers have autonomous responsibility for marketing decisions related to their brand. The distinction made between this and the brand managers in the centralized system is quite subtle. In general, brand-managed companies are considered decentralized.

In contrast to the brand management system is the single-brand company. When a corporation markets its product lines under one brand (Starbucks, McDonald’s), there is need for one brand manager, and that individual usually takes the title of marketing director, marketing manager, or chief marketing officer.

Megabrands

A third basic organization structure is that of the less-common megabrand (or superbrand). This is when a brand is seen as so well developed, successful, and powerful that it is leveraged and applied to all products, even when they are in completely different product categories and industry sectors.

The classic example is the Virgin brand. Founded by entrepreneur and tycoon Richard Branson, Virgin has expanded beyond its core businesses of travel and entertainment and now consists of more than 400 companies, most operated under the Virgin brand.

In terms of brand insulation, the opposite of what holds for brand managed companies is true for megabrands. If the brand is damaged through some negative event, all of the company’s operations could be tainted.

Lesson 2 Wrap-Up and Looking Ahead

Summary

This lesson examined the strategic communication functions of identifying markets, segmenting markets, target marketing, and positioning:

- Identifying markets and using market research techniques to find consumer groups with unmet needs.

- Understand the role of target marketing, the relationship between ease of measurement diagnostics, and how marketers use geographic, demographic, and psychographic variables to segment markets.

- The fundamentals of positioning including frame of reference, point(s) of difference, reason(s) to believe, and repositioning and rebranding.

By now, you should understand that the function of all elements of marketing communications programs is to communicate. Lesson 2 illustrated how companies target consumers and how they position their products or services in the marketplace. They are increasingly having to become more innovative in their approaches as it is becoming increasingly difficult to communicate with consumers through traditional media (e.g., TV, radio, print). Lesson 3 explores how those involved with the implementation of IMC programs need to understand the communications process and what it means in terms of how they create, deliver, manage, and evaluate messages about their company or brand. The lesson will also explore the fundamentals of communications and models on how consumers respond to advertising and promotional messages.

Check and Double-Check

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Looking Ahead

As discussed in Lesson 2, the fundamental differentiating device for products is the brand. Without brands, consumers couldn’t tell one product from another. Branding decisions can be difficult and that is why companies invest a significant amount of resources—human and capital—to build and protect their brands. In Lesson 3, the marketing process and the role of advertising and promotion in an organization’s integrated marketing communications (IMC) program will be explored. The concepts of target marketing and market segmentation will also be explored.

References

Arens, W. F., & Weigold, M. F. (2021). Contemporary advertising and integrated marketing communications (16th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Belch, G. E., & Belch, M. A. (2020). Advertising and promotion: An integrated marketing communications perspective (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Bendinger, B. (Ed.). (2004). Advertising & the business of brands. The Copy Workshop.

Bendinger, B. (2009). Advertising & the business of brands: an introduction to careers & concepts in advertising & marketing. The Copy Workshop.

Buffington, D., & Hassoun, B. (2020, January 27). Brands and lies in the post-truth era. Ogilvy. https://www.ogilvy.com/ideas/brands-lies-post-truth-era

Davis, S. M., & Dunn, M. (2002). Building the brand-driven business. Jossey-Bass.

Fripp, G. (n.d.). Understanding benefit segmentation. Market Segmentation Study Guide. http://www.segmentationstudyguide.com/understanding-benefit-segmentation/

Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2007). Made to stick: Why some ideas survive and others die. Random House.

Hertioga, C., & Christensen, J. (2018). What is a brand? Interbrand. https://www.interbrand.com/views/what-is-a-brand/

Hertioga, C., & Christensen, J. (2021, April 5). Why invest in branding? Interbrand. https://www.interbrand.com/london/thinking/why-invest-in-branding/

Ogilvy, D. (2010). Ogilvy on advertising. Prion.