COMM428B:

Lesson 1: U.S. Legal System

Lesson 1 Overview

Introduction

As discussed in COMM 428A: Principles of Strategic Communications, strategic communications are messages sponsored by a person or an organization that are part of a plan to achieve an objective. In the context of this course, the primary focus is advertising and marketing messages presented in an online environment. At the outset, we can easily recognize that advertisements and other marketing techniques to communicate a message constitute a type of speech. Therefore, the regulation of these messages must conform to the parameters established under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees a right to free speech. Before we explore how the government regulates strategic communications and how courts apply the First Amendment to commercial speech, we need a basic understanding of how the U.S. legal system works. That is the subject of this lesson.

Objectives

At the conclusion of this lesson, you should be able to

- identify the basic components of the legal system,

- distinguish between various types of law, and

- identify the role of courts and the precedents in interpreting laws.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

Lesson Outline

- Overview of U.S. Legal System

- How Laws Get Created

- Statutory and Regulatory Law

- Common Law

- Judicial System

- Precedent

Note on Terminology

Some legal terms have very specific meanings that are different from their everyday usage. For example, actual malice has a very specific meaning related to defamation that has nothing to do with the everyday meaning of the word malice (ill will or malicious intent). Throughout this course, we will be studying laws created by a variety of sources: Congress, state legislatures, federal agencies, state and local agencies, the president, state governors, and so on. We will use the terms law, regulation, and rule interchangeably to refer to any legal requirement that individuals and corporations must obey.

Important Note of Caution

Law is a very complex subject with important real-world consequences. Failure to follow the law can result in large fines, revocation of licenses, ruined careers, and in some circumstances time in prison! The purpose of this course is to help you identify common legal issues that may arise from online marketing and advertising. You should always seek legal advice from a qualified attorney before engaging in any behavior or strategy that raises legal issues. The law changes constantly. New laws are passed, and new court cases alter how the law is interpreted. While we make every effort to keep the course accurate and up-to-date, it is not a substitute for legal advice.

Please direct technical questions to the IT Service Desk.

Introduction to Law

Everyone is familiar with the basic concept of law, though few outside of the legal profession understand how laws are created and applied. Laws are rules that can be enforced (typically with some punishment or negative consequence for violating the law). The key components are the following:

- A rule that requires or prohibits certain behavior

- A range of consequences for violations of the rule

- A procedure for determining when a violation has occurred

Additional elements include the following:

- Who gets to make the rules and how?

- Who has to obey the rules and under what circumstances?

- How will the rules and consequences be enforced?

Let’s examine each element more closely. Select each component to learn more.

A Rule That Requires or Prohibits Certain Behavior

We face rules in many situations: No talking or sleeping during class; wait for your turn before rolling the dice in Monopoly, no drinking alcohol while driving; no shoplifting; no unsubstantiated health claims in an advertisement; and so on. We tend to think of rules as restrictions, but they can also be requirements: You must disclose foreign income on your tax return; you must obtain a driver’s license before driving a car; tobacco companies must disclose health risks on cigarette packaging; and so on.

A Range of Consequences for Violations of the Rule

Some rules have vague consequences. For example, what is the penalty for talking in class? Being asked to stop? Being asked to leave the room? A lower class participation grade? Other rules have specific consequences, including monetary fines, license revocation, or jail or prison time.

A Procedure for Determining When a Violation Has Occurred

Many violations are determined on an ad hoc basis. When you and your sister complain about each other to your parents, they often create the rule (and the punishment) on the spot! Referees and umpires in professional and amateur sports are tasked with enforcing the rules of the game. In the criminal justice system, there are an array of detailed procedures for determining when a violation has occurred.

Who Gets to Make the Rules and How?

We first learn rules from our parents, who have godlike power over us and can impose arbitrary rules on a whim. Voluntary organizations also have their own rules (and procedures for making them). For example, Penn State has countless rules and guidelines for faculty, staff, and students. Some are imposed by the central administration (president, provost, deans, etc.), while other rules are created by the University Faculty Senate. This raises the issue of jurisdiction—how far does an entity’s authority extend? For example, at Penn State, the faculty senate has some authority over curricular issues and whether a new major or course can be offered. But the faculty senate has little authority or jurisdiction over decisions about landscaping or building maintenance. Instead, it is the president of the university who gets to make decisions about landscaping, budgeting, and so on.

Professional organizations, companies, clubs, and social groups can all create their own rules. The local hiking club can create rules regarding who can be a member, annual dues, appropriate behavior or attire on club outings, and so on. The Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) can set the requirements for membership and suspend or expel members who violate its code of ethics.

Who Has to Obey the Rules and Under What Circumstances?

We quickly learn who we have to obey—who has jurisdiction over us. We have to obey our parents—as long as we are living at home. But once we are adults and move into our own apartment or house, our parents’ power over us is substantially reduced (though guilt can be a pretty powerful enforcer even from a distance!). Another example is that PRSA’s code of ethics only extends to its members. If you are not a member of PRSA, it cannot punish you. Even if you are a PRSA member, its jurisdiction extends only to certain circumstances and situations. If you lie to or on behalf of a client, you may be expelled. But if you lie to your spouse or parents, that is beyond the purview or reach (or jurisdiction) of PRSA.

How Will the Rules and Consequences Be Enforced?

Most organizations have written procedures for (1) creating rules, (2) determining violations, and (3) enforcing consequences. This is true for organizations like PRSA, universities like Penn State, and local, state, and federal governments. The introductory textbook chapter assigned for this lesson (Mass Media Law, Chapter 1) details the various sources of law within the American legal system. What makes the legal system different from organizations like PRSA or Penn State is that the government has the power to enforce its rulings through coercion (confiscating money and property or physical incarceration in prison).

Overview of the U.S. Legal System

Before beginning our legal analysis of strategic communications, a brief review of the U.S. legal system is in order. Later, we will also discuss international regulations as appropriate. The U.S. Constitution is the "supreme law" of the United States. You can think of the Constitution as a rule book that provides instructions for how the government will operate and what the government is allowed to do. Just as the board game Monopoly has a certain set of rules that all players must follow, the government also has rules it must follow.

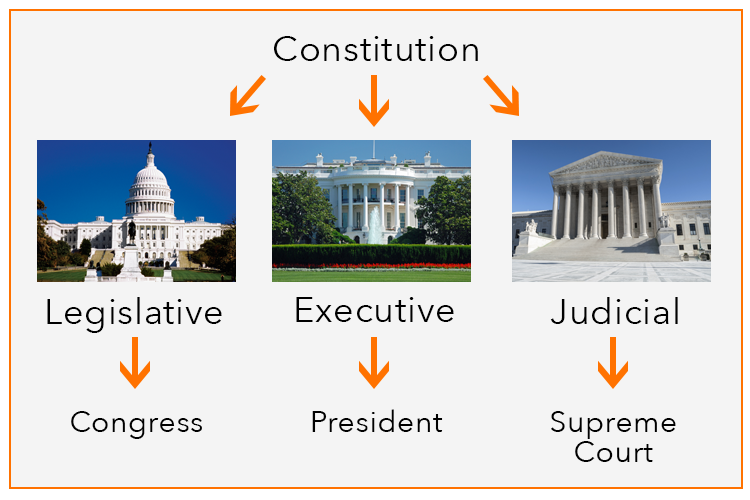

The Constitution details what the executive branch (the president), the legislative branch (Congress), and the judicial branch (the courts) are each supposed to do. One job of the Supreme Court is to make sure that each branch does not overstep its authority. In addition, the Bill of Rights and other amendments to the Constitution specify certain individual rights that the government is not allowed to restrict. For example, if Congress passed a law prohibiting all advertising on television, the Supreme Court would strike down the law as unconstitutional because it would violate the right of free speech protected by the First Amendment.

Each state has its own constitution that establishes that state's system of government. A state legislature must follow the rules in the state constitution just as Congress must follow the rules in the federal constitution. In addition, the rights granted to individuals by the federal constitution apply to all the states as well, so a state or local government is not allowed to restrict your free speech either.

How Laws Get Created

Since most states operate similarly to the federal government when making laws, we will focus on the federal process for now. There may be slight variations in how the process occurs in a particular state, but this overview describes the basic process. To create a law, a member of Congress first proposes it as a bill. The bill is studied by a congressional committee, debated, and revised. Most bills "die" in committee and are never presented to the full Congress for a vote. If the House version of the bill and Senate version are different, a joint committee negotiates changes until the two versions are identical. Finally, Congress votes on the bill. If the bill passes, it's sent to the president. If the president signs the bill, it becomes law. Then, it's up to the courts to interpret how the law should be enforced. Sometimes the law is easy to interpret. For example, when you are playing Monopoly and land on the "Go to Jail" square, the instructions say to "go directly to jail, do not pass GO and do not collect $200." There isn't much room for interpretation of that rule!

Watch the following video to understand the basics of how a bill becomes a law.

The rules of Monopoly also say to roll both dice and move the appropriate number of spaces. But what if one of the dice falls on the floor while you are rolling? Are you supposed to reroll that die or use whatever number appears on the floor? The rules don't provide an answer for that situation, so the players have to decide (interpret) what the rule should be. Now, suppose when you roll the dice, one die lands on a surface that isn't flat. Do you reroll or do you use whatever number appears to be facing up? This is another decision you must make that isn't specified in the rules. In our legal system, the judicial branch (the courts) has to make those decisions by interpreting the intent of the law. When a court interprets a statute or administrative rule, it's called statutory construction.

How does a court interpret the meaning of a particular law? First, the court will look at the actual text of the law to see if the law itself provides an answer. In our example above, the Monopoly rules are very specific about what happens when you land on "Go to Jail." If the text of the law doesn't provide an answer (such as what to do when the dice land on the floor), the court will read the reports that Congress wrote when it passed the law. Those reports provide insight into why Congress passed the law and how Congress thinks the law should be interpreted. These reports often help a court in interpreting a specific section of a law. In addition, a court will look at how that specific section of the law has been interpreted by other courts in previous cases. Every time a court interprets a law, it creates a precedent that other courts can follow in future cases. We will discuss precedents in more detail later in this lesson.

Statutory and Regulatory Law

When Congress or a state legislature passes a law, it's known as a statute. We think of most federal laws originating in Congress, but many rules are made by government agencies. Agencies are created by Congress (or a state legislature) and are usually controlled by the executive branch. When an agency passes a law, it's known as a regulation. Even though these regulations are not made by Congress, they still have the same force of law. For example, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) creates rules for broadcasting and cable. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) makes rules for airlines and airports. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) makes rules about food labeling and prescription drugs. All these agencies have their own procedures for creating regulations just like Congress has procedures for creating laws. We call these agency rules regulations instead of calling them laws, but you have to obey regulations just like you have to obey laws!

As a side note, the procedures for creating agency regulations are usually more complex than the procedures Congress has to follow when creating laws. This is because members of Congress are elected by citizens, so if members of Congress pass a law that you don't like, you can try to vote them out of office. In other words, members of Congress can be held accountable for their votes. Agency officials are usually appointed by the president (or, at the state level, a governor). There's no way to vote out a member of the FCC or the FDA since they aren't elected. Therefore, agencies have to follow extra procedures to make sure the process is fair, and they don't abuse their power. For example, the public must be given an opportunity to comment on proposed regulations before they are enacted. The procedures that agencies must follow are known as administrative law.

Businesses that are unhappy with a law passed by a legislative or administrative body will often challenge the new law in court. When reviewing and interpreting laws and regulations, courts typically have two key considerations.

First, did the legislature or agency follow the proper procedures in creating the law? Some procedures are required by the Constitution, while other procedures are created by the legislature or agency itself. If the proper procedures weren't followed, then the law or regulation may be thrown out by the court.

Second, did the legislature or agency overstep its authority? There are two ways of overstepping authority:

- The agency or legislature operates outside its jurisdiction. For example, the FAA was created by Congress to regulate air travel. If the FAA passed a regulation about cars or trucks, a court would say the agency has exceeded its authority since automobiles and trucks are not within the FAA's jurisdiction. (Note that Congress could pass a new law giving the FAA jurisdiction over cars or trucks if it wanted to.)

- The government passes a law that infringes on constitutional rights. For example, the FAA has authority over airplanes, but it cannot require everyone to undergo a strip search before getting on an airplane because this procedure would be considered an unreasonable search in violation of the Fourth Amendment. So even though the FAA has the appropriate jurisdiction to regulate air travel, it still cannot violate the rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

Remember that every state has its own constitution, so state and local government entities have to follow the state constitution as well as the federal constitution. For example, if the city of Pittsburgh passed a regulation restricting the use of Facebook, a court would ask

- did the city follow the proper procedures in passing the regulation,

- does the regulation exceed the city's authority under the state constitution and state law, and

- does the regulation violate citizens' rights under the state constitution and the federal constitution?

The process of evaluating whether a law is constitutional is known as judicial review.

Common Law

Another type of law is called common law. Common law refers to rules that are developed over time by the courts instead of created by the legislative or executive branch. These court rulings are based on centuries of social customs. For example, suppose you have a broken set of steps leading to your front door, and someone is injured as they try to knock on your door. You can be sued for negligence and forced to pay for the person's medical treatment even though there is no statute or written law against having broken steps. The court would say that, as a homeowner, you're responsible for hazardous conditions on your property. The court would be using the common law to decide the case rather than a specific statute passed by the legislature.

When one person does something that causes harm to another person, the person who was harmed might sue to receive compensation for the harm caused. For example, most states don't have a specific law prohibiting you from taking and publishing a photo of someone who is sleeping in a hospital bed. But if you do take and publish such a photo, the person might sue you for invasion of privacy. You haven't violated any specific law, but you still might be forced to pay damages for the harm you caused (emotional distress and embarrassment).

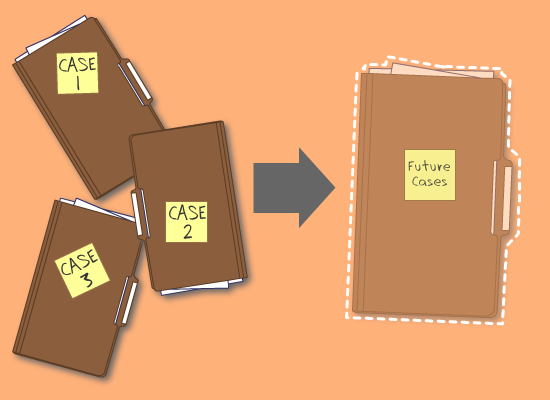

Courts have heard many cases related to invasion of privacy. Over time, all these court decisions become unwritten rules. Let's say that 30 years ago a court considered a case where someone published a photo of a woman giving birth. At the time, the court said that this was an invasion of the mother's privacy, and the photo shouldn't have been published without her permission. Maybe 5 years later there was a case where a man sued after a photo was published of him having surgery, and he also won his case. A few years later, a woman won her suit when a photo was published of her wearing a hospital gown. Now we have three different cases where the court decided that publishing a photo of a person in the hospital was an invasion of privacy. In future cases, the court will try to apply the same logic and rule based on these previous decisions (Figure 1.2 illustrates this idea). This is how the common law develops. The common law gives the judicial system a way to deal with cases where there is no written rule but there is a dispute between private individuals.

Judicial System

To study legal issues, you must have a basic understanding of how the judicial system works. Each state has its own judicial system, which typically follows the same basic structure as the federal judicial system. In a criminal case, the government prosecutes an individual (the defendant) for violating a criminal statute. The government must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt, and if the defendant is found guilty, the verdict can result in jail time. In a civil case, one party (the plaintiff) sues another party (the defendant), and the court acts as a neutral arbiter to resolve the case (like an umpire or referee at a sporting event).

Most court cases take place in a trial court where each side presents evidence supporting its version of the facts. The judge or jury weighs the evidence to determine the facts. The law is then applied to those facts to determine the result of the case. The losing side will often appeal the verdict to an appellate court. The appellate court will determine whether the law was applied correctly and whether proper procedures were followed.

The purpose of a trial is (1) to determine the facts and then (2) apply the appropriate law. Sometimes there's a dispute about the facts. In our Monopoly example, if the die landed on an uneven surface, which number was facing up? Or, to use a football example, did the receiver step out of bounds under his own power before catching a pass, or was he pushed out? Each side presents its witnesses, and the judge or jury determines the facts based on the evidence.

Once the facts have been determined, the judge or jury applies the law. For example, if the receiver stepped out of bounds, he's ineligible to catch the ball, but if the receiver was pushed out of bounds, he's allowed to come back onto the field to make the catch. If you're drunk and kill someone with your car, it may be considered vehicular homicide, whereas if you're sober and have a heart attack and kill someone with your car, it may be considered a no-fault accident. So the first step is to determine the facts, and the next step is to apply the appropriate law to those facts.

Often, the losing side in a court case can appeal the decision. Whichever party appeals the case is the appellant, and the other party is known as the appellee, or respondent. Normally, you can appeal a case only if (1) the court did not follow the proper procedures or (2) the court applied the law incorrectly.

Hierarchy of Laws

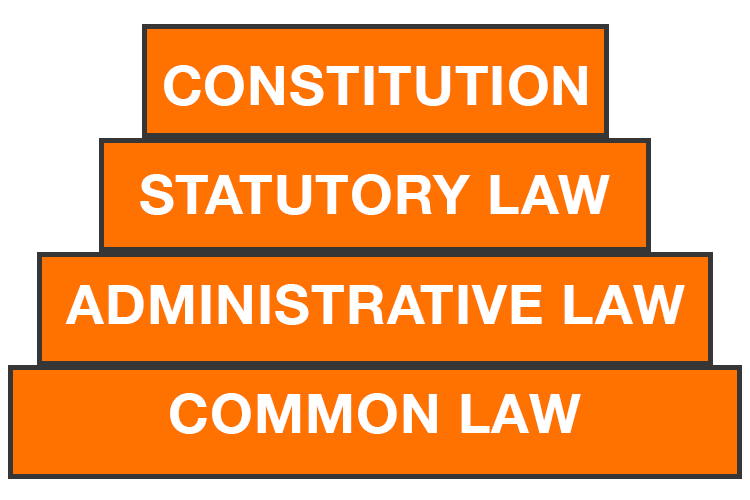

We've discussed various sources of law: federal and state constitutions, statutory law, administrative law, and common law. What happens when there is a conflict between different sources of law? For example, suppose a state legislature passes a law saying that it's now permissible to publish photographs of patients in a hospital. This statute would conflict with the established common law that allows patients to sue for an invasion of privacy. In this case, the statute would take precedence over the common law.

Think of a military unit where there is a hierarchy of command: a private must obey a sergeant; the sergeant must obey a captain; a captain must obey a general; and a general must obey the commander-in-chief. Laws also have a hierarchy. Figure 1.3 provides an illustration. At the top is the Constitution. Whenever any other type of law conflicts with the Constitution, a court must follow the Constitution. Next in the chain of command is statutory law, then administrative law, and at the bottom, common law. If an administrative law conflicts with a statutory law, the court must follow what the statute says, and so on.

Precedents

As discussed earlier, courts have to interpret the meaning of a law in order to enforce it. The judicial system tries to be fair and predictable so that everyone knows what is and isn't allowed. Think back to the Monopoly example. Suppose you roll the dice, and one falls on the floor. If this were a court case, the judge might rule that you should reroll that particular die. This ruling creates a precedent for future cases. If the same thing were to happen later in the game, you would expect the judge to follow the same rule again. This use of precedent helps ensure fairness and consistency.

In the legal system, courts have to decide which precedents are most appropriate for any particular case. Suppose you roll the dice, and one die lands on top of a book lying next to the game board. One player says that landing on the book is just like landing on the floor because the die is not on the game board; therefore, you should reroll that die. Another player says that the die landing on the book is different than landing on the floor because the book is still on the table, not the floor. According to the second player, you don't have to reroll the die. If this were a court case, the first player would be trying to convince the court to accept the precedent of rerolling the die. The second player would be trying to convince the court that the facts of the new case (the die landing on the book) are different enough from the original case (the die landing on the floor) that the court is not obligated to follow the original precedent. If the court agrees with the second player, it has distinguished the precedent. The court is saying that the facts of the new case aren't the same as the facts in the first case; therefore, the court isn't bound to follow the decision it made in the first case.

A court can also modify a precedent. Suppose the original case involved the die falling onto a carpeted floor. Now imagine a new case where the die falls onto a wood floor. The court might determine that a reroll applies when a die falls on carpet because it isn't a flat surface. But the court might also say that a reroll doesn't apply when a die falls on wood because the wood is a flat surface. Here, the court would be modifying the precedent by saying it only applies to floors that aren't flat and smooth. In very rare cases, a court may say the original precedent was wrong and should be overruled.

Technically, precedent only applies in common law cases when there is no specific regulation applied to the situation. When the court deals with a statute or regulation, the interpretation on the law is called statutory construction. But as with common law cases, once a court has conducted statutory construction (e.g., ruling that the dice must land on the game board), future courts will use the same statutory construction and follow the decision (precedent) established by the first court.

Binding vs. Non-Binding Precedents

Just as there is a hierarchy among types of law, with constitutional law superseding (overruling) statutory law and statutory law superseding administrative law, there is a hierarchy of courts that determines which precedents are binding and must be followed.

A trial court has to follow only the precedents of courts within its direct chain of command. For example, a Pennsylvania trial court must follow the precedents established by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. But a Pennsylvania trial court does not have to follow the precedents of the Ohio Supreme Court or the New Jersey Supreme Court (just like an employee in the accounting department of a company usually doesn't have to take orders from a manager who supervises the assembly line).

As you learned in the textbook, the federal court system is divided into regions called circuits. For example, Pennsylvania is located in the Third Circuit, New York is located in the Second Circuit, and California is located in the Ninth Circuit. So when the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit creates a precedent, that precedent is binding (must be followed) by all courts located in the Third Circuit. Courts in other circuits (like New York or California) do not have to follow the Third Circuit precedent. However, a court in the Second Circuit can choose to follow the Third Circuit precedent as long as it doesn't conflict with any precedent already established in the Second Circuit. In other words, precedents in one circuit are often influential and adopted by other circuits as well. All state and federal courts must follow precedents created by the U.S. Supreme Court, which is why Supreme Court cases are considered so important.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction refers to which court has the authority to hear a particular case. For example, if you live in Pennsylvania, and someone makes a defamatory statement about you in Florida, where can you file your lawsuit? Can you file your suit in a Pennsylvania court, or do you have to sue in a court in Florida, where the defendant lives? What if the statement was posted on a website, and the computer that hosts that website is located in Virginia? Can you sue the defendant in Virginia? What if the defamatory statement is read by someone living in New York? Can you sue in New York? The question is which state can be the forum where the case will be heard.

There are many types of jurisdiction, with complex rules that are beyond the scope of this course. The most important points to understand are the following:

- You may have to appear in court wherever you intentionally send your marketing messages and wherever your company does business.

- You generally have to follow the laws and rules wherever you do business.

Wherever you intentionally send your marketing messages and wherever your company does business

A business can always be sued in the state where it is incorporated and the state where its headquarters are located. Typically, it can also be sued in states where it maintains offices or employs a workforce. Depending on the circumstances, it can also be sued where it sells or ships products and where it intentionally disseminates marketing messages. If your organization is based in Pennsylvania, and you purchase advertising time on a New Jersey radio station or in a New Jersey newspaper or on a New Jersey–focused website, then you could be sued in New Jersey if you cause any harm there.

Less clear is whether a business can be sued in another state simply because someone in that location viewed its marketing messages. For example, if your business is located in Pennsylvania and someone in Nevada views the website, that does not mean they can sue you in Nevada. Similarly, if you live in Pennsylvania and post a negative review about a company based in Michigan, that does not mean the company can sue you in Michigan. The more contact you have with a state, the more likely it is that you can be sued in that state if you cause any harm there related to your conduct that causes harm in that state.

Wherever you do business

Companies are responsible for knowing the laws (and collecting sales tax) in any state where they do business. The same is true internationally as well. For example, Facebook and other social media companies that operate in the European Union must follow all of the EU privacy laws when collecting data in the EU. California has stricter product safety laws than many other states. If you market and sell your products in California, you must comply with its laws.

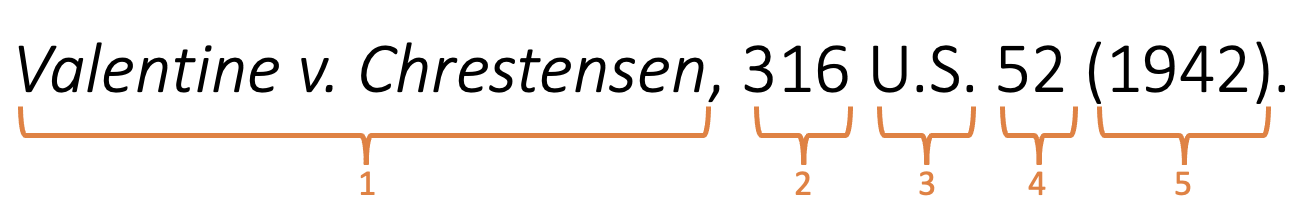

How to Find Cases, Statutes, and Articles

Throughout this course, we will be discussing laws and court cases. There are a variety of ways to find these documents online. Understanding the citation method used in legal research is vital for finding this information. You've probably used a citation style when writing a research paper or even in a business report. The purpose of a citation is to help the reader find the source of information that was used. Legal citation uses a very specific style which looks confusing but is actually straightforward. Court cases are published in journals called reporters. For example, United States Reports publishes all U.S. Supreme Court cases. Just like magazines, the cases are grouped by volume number. For example, Volume 1 of Time magazine was published in 1923, with a new issue published each week. With legal citation, the volume number is placed before the abbreviated title of the reporter, and the first page of the case is listed after the abbreviated title. For example, later in this lesson, you will read the case of Valentine v. Chrestensen. The case was decided by the Supreme Court in 1942. The opinion was published in United States Reports, Volume 316, beginning on page 52. If you went to the library, you would find a huge shelf with all of the volumes of United States Reports. If you pull Volume 316 off the shelf and open that volume to page 52, you will see the Valentine v. Christensen opinion. The opinion will then go on for many pages (it ends on page 55). The citation would look like Figure 1.4.

The format of the citation follows a pattern:

- Names of the two parties: This case was a dispute between Lewis Valentine, the Police Commissioner of New York City, and F. J. Chrestensen, the owner of a submarine. A lower court (Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit) had ruled in favor of Chrestensen. Valentine appealed, asking the Supreme Court to reverse the decision. Since Valentine is the party that is appealing, his name comes first.

- Volume number: In this example the volume number is 316. Most citation styles (APA, MLA, etc.) put the volume number after the title of the publication (New York Times, Vol. 86 or Rolling Stone, Vol. 23, etc.) for other types of publications. For court cases and law review articles, the volume number comes before the title of the publication.

- Abbreviated title of the publication: U.S. is the abbreviation for United States Reports, one of the reporters that publishes Supreme Court cases (just like you might abbreviate the New York Times as NY Times).

- Beginning page number: For this example, the particular case or article is 52. Note that only the first page of the case is listed in the basic citation. However, if you were referring to a particular section of the case, you would include that page number too—for example: 316 U.S. 52, 54. This tells the reader that the court opinion begins on page 52, but that the part of the opinion you are discussing can be found on page 54. Legal citations are very precise because judges and lawyers must be able to see the specific part of the precedent they are considering.

- Year the case was decided: The last information provided is the year the case was decided (1942).

As you read cases, you'll start to get used to the citation style. At first it's very confusing to see all these random numbers and abbreviated titles, but they all refer to a specific part of a specific case or specific sections of a statute or law. Sometimes the same case is published in multiple reporters, just as the same Associated Press newspaper article might be published in multiple newspapers. You may then see a long string of citations, telling you the volume and page number where the case can be found in multiple reporters. Imagine citing an AP News story and including the citation for the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and the Orlando Sentinel. All three citations are referring to the same story, but it's published in a different volume and different page number for each publication.

Court Levels

Throughout this course, we'll spend a lot of time reading federal court cases. Each level (district courts, circuit courts, U.S. Supreme Court) has its own reporter. Thus, the citation for each case provides clues to where the case fits within the hierarchy of courts. Remember that Supreme Court decisions are binding on all lower courts, whereas Circuit Court of Appeals decisions are binding only on courts within that circuit. District court opinions are not binding but may be influential. Once a reporter publishes 999 volumes, it starts a new series (2d, 3d, 4th, etc.). Table 1.1. provides the names and abbreviations of all the reporters in the U.S. legal system.

| Federal Court | Reporters (with abbreviations) |

|---|---|

| Supreme Court |

United States Reports (U.S.) |

| Circuit Court of Appeals | Federal Reporter (F. and F.2d and F.3d) |

| District Court | Federal Supplement (F. Supp. and F. Supp. 2d and F. Supp. 3d) |

So when you see U.S. or S. Ct. in the citation, you know it's a Supreme Court case. When you see F. or F.2d or F.3d, you know it is a Circuit Court of Appeals case (with the specific circuit in parentheses), and when you see F. Supp. or F. Supp. 2d or F. Supp. 3d, you know it is a district court case.