Main Content

Lesson 2: Measurement of Crime and Crime Decline

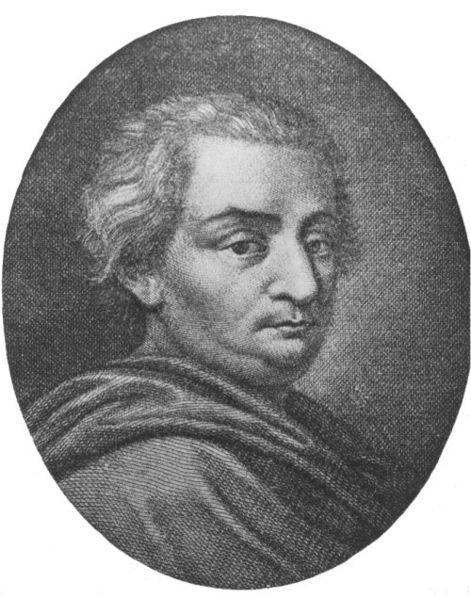

The Father of Classical Criminology: Cesare Beccaria (1764)

During the 1700s across Europe and in the early American colonies, there was no codified system of laws. A person could accuse another person of some inappropriate act either toward his/her property or person and local leaders, often clergy or leaders in the church community, would engage in ex post facto law making (i.e. law making after the fact). In order to bring individuals to justice, local communities engaged in rather barbaric practices, at least by today's standards. Torture was widespread and ranged from public whippings to outright death by severe and rather painful means. It was against this backdrop that Beccaria and a band of political philosophers began to meet to discuss alternatives to torture and make recommendations for a new kind of justice system.

In On Crimes and Punishment, Beccaria outlined such recommendations, including calling for a system of laws that were written down and that explained precisely what the punishment would be for breaking them. He argued against torture, against the death penalty, and he believed that close attention should be paid to ensuring that punishment was swift, certain, and did not go too far. In other words, Beccaria believed that people weigh the costs and benefits of their actions such that punishment should be just enough to make crime too risky a business. Torture was not necessary, argued Beccaria, under such a system. Besides, a weak person would confess to anything under pain and suffering at the hands of a torturer while a strong person might be able to bear quite a bit. This could lead to guilty persons being let go and the miscarriage of justice by punishing an innocent man or woman.

At the heart of Beccaria's theory, today referred to as Classical Criminology, is the notion of free will. All humans have the capacity to think about their actions; this is what separates humans from other animal species. Because all humans are able to reason, laws and punishments should be enacted that focus solely on the act itself, and not on the actor. Everyone should be treated alike, regardless of gender, race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, etc. If a particular law is broken, the punishment, spelled out as part of the law itself, should be set and it should be known by would-be offenders.

We talk about the legacy of Beccaria as much of what he agitated for is alive and well in today's modern-day criminal justice system. Too, his ideas provide the backdrop and the intellectual foundation for a great deal of theoretical development and testing across the past 20 years or so. Yet, there are several ideas of Beccaria that often go under-utilized and that receive a minimal amount of attention in theoretical classrooms.

- First, Beccaria argued that it was better to prevent crimes from occurring in the first place than do try to do something about it once it occurred. Could he have been an early proponent of intervention programs for at-risk youths? Or, might he agree with some positivist theorists that one's environment might play a role in crime production?

- Second, Beccaria also was opposed to the death penalty. He believed that capital punishment was not working to bring down a reduction in crime, just as torture was not working. Some argue that Beccaria saw such infliction of pain and death at the hands of the government as creating a barbaric society, or at least to be a contributor to such a society. Beccaria did argue, however, that if a person could find a way to bring down the government from inside a prison cell, he/she should be exterminated. That is to say, if such an individual were able to maintain connections with those who would commit treason against the government and able to yield a great deal of influence over such actions, then the best course for government would be to terminate such an individual. But only under such circumstances would Beccaria be in favor of the death penalty.

One can understand why On Crimes and Punishment was banned by the Catholic Church and why Beccaria had to go into hiding for a period of time. Although his ideas fit very nicely with modern-day thought, they went against the Spanish Inquisition and other church-led attempts to continue down a path of torture and death throughout the 1700s and even into the early 1800s in some parts of the world. Eventually, however, human societies turned toward a more humane method of punishment and sought a system of justice grounded in the notion of innocent until proven guilty as opposed to guilty until proven innocent.