CRIMJ12:

Lesson 2: Measurement of Crime and Crime Decline

Measurement of Crime and Crime Decline

Lesson Overview

The purpose of this lesson is to learn about how crime is measured by criminologists, and how rates of crime (crime trends) have changed over time. This first lesson provides a discussion of how crime is tracked and measured and thus provides the student with an essential “first step” in understanding crime trends (in the following lesson). Understanding crime measurement (and the limitations of these crime data sources) will also help to inform the rest of the course by allowing students to more effectively evaluate theories of crime, and particularly those theories that were developed based in part on analyses of these sources of crime data.

In regard to the second lesson (rates of crime and crime declines), the trends allow for an identification of factors that drive rates of crime and an understanding of how myriad diverse factors work in unison to shape empirical phenomena such as crime rates. An identification of crime rate trends and how they have changed over the past several decades also allows for an understanding of how criminal justice policy developed, and the subsequent impact of criminal justice policy ideas on crime rate trends. For example, we will learn that many of the criminal justice policies endorsed today were implemented in the 1970s, and in some instances have led to unintended consequences (such as the dramatic expansion of the use of prison as a correctional option to address even minor violations of law, such as in cases of drug possession, or technical violations of probation). Alternatively, other factors impacting the level of crime in the society have nothing at all to do with law or criminal justice policy.

This lesson is aimed at introducing the student to two of the major data sources used in criminology to understand the dispersion of crime in the society, and to understand the strengths and weaknesses of these data sources, and how they can be used to identify crime trends- which provides opportunities to develop new theories of crime, or revise existing theories.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Define the two major data sources criminologists use to assess levels of crime and crime trends.

- Identify the limitations of these two data sources, as well as what they are particularly good for.

- dentify the causes of the crime decline that began in the early 1990s.

- Understand and describe how changes in crime rates are the result of an amalgam of other changes in the social body.

- Recognize the importance of some of these factors for developing theories of crime causation, as well as policy prescriptions that might be logically suggested by these factors.

Please complete the readings and assignments outlined in the course schedule for this week.

Thought-Provoking Exercise

|

Think about a time in your life when you might have engaged in somewhat inappropriate behavior. Or, think about a time when you might have been at a crossroads in your life, where turning to the right would lead to one set of circumstances, and turning to the left would lead to another different set of circumstances. Of course, you could also back up, or continue straight ahead! But whatever decision you made about which direction to take resulted in a set of circumstances that might have been different had you chosen a different direction. Now think for a moment about the amount of time and effort you spent in thinking before you acted. Without disclosing any personal/private information, what were your thoughts just prior to engaging in the behavior of your choice? Did you carefully weigh your options and/or think about what might result from your behavior/choice? Post your thoughts and respond to at least one of your classmate's comments to the Lesson 2 Thoughts and Behaviors discussion forum located in the Lesson 2 Activities folder. |

Reading Assignments

Reading Assignments

-

Chapter 2 in Bernard, Snipes, and Gerould's Vold's Theoretical Criminology. You are expected to have completed the reading before you proceed to the instructor's commentaries for this lesson.

- Review the Lecture on Classical Criminology.

- Refer to the figures that demonstrate the major propositions and concepts of Cornish and Clark's rational choice theory.

- Take the RAT 02 (Reading Assessment Test for Chapter 2).

Summary

With the materials presented here, along with the PowerPoint lecture presentation, I hope you have an understanding of how crime is measured and tracked, and of the importance of thinking about crime epidemiologically (in terms of patterns, and trends) and how this is a useful precursor to thinking about and evaluating theories of crime that will be presented as the course moves forward. It is important to remember that understandings of crime causation derive in part from our understandings of how much crime there is in a society, where crime is disproportionately located, and how the dispersion of crime varies not only across place, but over time. Even though these data sources have important limitations that necessarily underestimate the “true” extent of crime in the society, it is nevertheless important to understand how crime is measured and what these data tell us about the prevalence of crime in the society, as legislators and the police often make decisions about resource allocation based on a close examination of these data.

In thinking about the so-called “great American crime decline” it is also important to note that the trends we can observe in America are also observable across most of the Western world. That is, in nations like Britain, Australia, and so forth, rates of crime also began declining in the 1990s after rising steadily for a number of years. So in thinking about reasons for the decline, it is also important to not to be insular by considering social changes and developments that only affect the U.S. and North America. One example would be the global decline in levels of toxic lead in the environment, which was a socioenvironmental change that was seen in the US as well as the rest of the world, and which will be discussed later in the course. Such factors then become incorporated into the theoretical paradigms presented in the ensuing lessons and chapters, and just like crime rates, theoretical paradigms change over time, becoming more sophisticated as understandings of social and environmental factors (and their interplay) become more refined, incorporating new knowledge. And just like crime rate data tracked by the UCR and NCVS, various theories provide a filtered, or partial view of crime as a social phenomenon, with each theory having a piece of the overall puzzle.

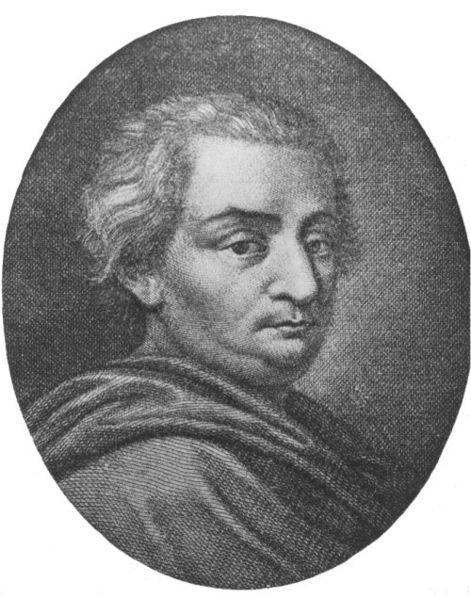

The Father of Classical Criminology: Cesare Beccaria (1764)

During the 1700s across Europe and in the early American colonies, there was no codified system of laws. A person could accuse another person of some inappropriate act either toward his/her property or person and local leaders, often clergy or leaders in the church community, would engage in ex post facto law making (i.e. law making after the fact). In order to bring individuals to justice, local communities engaged in rather barbaric practices, at least by today's standards. Torture was widespread and ranged from public whippings to outright death by severe and rather painful means. It was against this backdrop that Beccaria and a band of political philosophers began to meet to discuss alternatives to torture and make recommendations for a new kind of justice system.

In On Crimes and Punishment, Beccaria outlined such recommendations, including calling for a system of laws that were written down and that explained precisely what the punishment would be for breaking them. He argued against torture, against the death penalty, and he believed that close attention should be paid to ensuring that punishment was swift, certain, and did not go too far. In other words, Beccaria believed that people weigh the costs and benefits of their actions such that punishment should be just enough to make crime too risky a business. Torture was not necessary, argued Beccaria, under such a system. Besides, a weak person would confess to anything under pain and suffering at the hands of a torturer while a strong person might be able to bear quite a bit. This could lead to guilty persons being let go and the miscarriage of justice by punishing an innocent man or woman.

At the heart of Beccaria's theory, today referred to as Classical Criminology, is the notion of free will. All humans have the capacity to think about their actions; this is what separates humans from other animal species. Because all humans are able to reason, laws and punishments should be enacted that focus solely on the act itself, and not on the actor. Everyone should be treated alike, regardless of gender, race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, etc. If a particular law is broken, the punishment, spelled out as part of the law itself, should be set and it should be known by would-be offenders.

We talk about the legacy of Beccaria as much of what he agitated for is alive and well in today's modern-day criminal justice system. Too, his ideas provide the backdrop and the intellectual foundation for a great deal of theoretical development and testing across the past 20 years or so. Yet, there are several ideas of Beccaria that often go under-utilized and that receive a minimal amount of attention in theoretical classrooms.

- First, Beccaria argued that it was better to prevent crimes from occurring in the first place than do try to do something about it once it occurred. Could he have been an early proponent of intervention programs for at-risk youths? Or, might he agree with some positivist theorists that one's environment might play a role in crime production?

- Second, Beccaria also was opposed to the death penalty. He believed that capital punishment was not working to bring down a reduction in crime, just as torture was not working. Some argue that Beccaria saw such infliction of pain and death at the hands of the government as creating a barbaric society, or at least to be a contributor to such a society. Beccaria did argue, however, that if a person could find a way to bring down the government from inside a prison cell, he/she should be exterminated. That is to say, if such an individual were able to maintain connections with those who would commit treason against the government and able to yield a great deal of influence over such actions, then the best course for government would be to terminate such an individual. But only under such circumstances would Beccaria be in favor of the death penalty.

One can understand why On Crimes and Punishment was banned by the Catholic Church and why Beccaria had to go into hiding for a period of time. Although his ideas fit very nicely with modern-day thought, they went against the Spanish Inquisition and other church-led attempts to continue down a path of torture and death throughout the 1700s and even into the early 1800s in some parts of the world. Eventually, however, human societies turned toward a more humane method of punishment and sought a system of justice grounded in the notion of innocent until proven guilty as opposed to guilty until proven innocent.

A Historical Perspective of Theories in Crime and Delinquency

To the historical timeline of criminological thought you will now see where the two modern-day deterrence theories fit within the larger perspective. As theorists departed, although not entirely, from the earlier notions of Classical Criminology and embraced Lombroso's work with biological theory, free will and other ideas associated with deterrence theory were put on the back burner for a period of time. When it appeared, however, that efforts at rehabilitation under positivism had failed to deter crime, there was a great deal of renewed interest in the ideas of Beccaria. Thus, two modern-day theories of crime that are grounded in major concepts from the Classical perspective found their way into the criminal justice policy arena. Once again, society began to think about deterring crime through swift and certain punishment, making sure that criminals knew that crime absolutely would not pay, and implementing a series of tough consequences for repeat offenders (e.g. "three strikes and you are out" legislation, mandatory minimum sentences, and expansion of capital offenses, etc.). These ideas and policy approaches are still very much alive and well today in the 21st century.

Figure 2.1: The Evolution of Ideas about Crime and Punishment

Summary

At the beginning of this lesson you were asked to think about a time when you had a choice to make as to which direction you would take or whether you should refrain from a certain act. That exercise was meant to have you think about the merits of rational choice theory and the notion of deterrence. Now, please think about that same event from a somewhat different perspective. Do you think that the choice you made, about which direction to take or the decision to engage in the type of behavior about which you are thinking, could have been influenced by factors other than your fear of negative consequences or hope for positive consequences? What else might have constrained you or pushed you toward your decision? You may be thinking about such things as: (1) modeling other people's behavior; (2) your home environment; (3) peer pressure; etc. etc. etc. Or, you may have been under the influence of some substance (alcohol or some illicit substance). It is also possible that your behavior was influenced by something internal to your biological or psychological system. As we will learn next week, positivist criminology, unlike classical criminology, focuses on the actor and his/her internal and external environment. Under positivism, you will learn that the choices one makes are multi-causal in nature; that there is much more to it than free will and rational choice.