CRIMJ230:

Lesson 2: Evidence-based Corrections

Lesson 2: Evidence-based Corrections

Lesson Overview

This lesson covers some basics of evidence-based corrections. In this context, the term "evidence" doesn't refer to criminal or forensic evidence, as would be used in a police investigation or criminal trial. When we talk about "evidence-based corrections," the term evidence refers to scientific or social-scientific evidence that is used to identify the most effective practices or policies for a desired outcome.

Lesson Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students should be able to:

- Define evidence-based practice and discuss its use in corrections.

- Explain the necessity of professionalism for corrections professionals.

- Explain the relevance of race/ethnicity and gender in the correctional discipline.

Building Up Your Knowledge

Social Science and Evidence-based Practice

Evidence-based practice is built around the scientific process, and more specifically the social-scientific process.

Social science

In general terms, the scientific method is an ongoing and cyclical process of observation, hypothesis testing, analyzing data, and creating and refining theory. The benefit of the scientific method is that by focusing on observation, we protect against our innate and often-invisible biases about what we think we're going to see.

The physical sciences like chemistry or physics are concerned with subject matter that is relatively stable. Things like chemicals, atoms, energy, and other physical phenomena are pretty much the same all over. So, for example, pure water is always going to be a liquid at what we would consider room temperature. The physical properties of water are dependable.

The social sciences are different than physical sciences because human behavior is the subject matter. There are two things you need to know about human behavior:

- People have their own minds. Each person has a very unique and complicated brain, and everyone's decision-making process is different. Any given individual's behavior is difficult if not impossible to predict.

- Human behavior, when looked at in the aggregate (meaning, when you look at the general behavior patterns of lots of people) will have patterns to it. So we can understand human behavior probabilistically. This means that we can watch how people act when they experience a general situation and note probabilities of types of responses.

Point 1 above tells us that we're never going to be able to predict any particular person's behavior. However, Point 2 allows us to create strategic approaches to certain types of behavior based on the general probability of success.

Example: Helping people with heroin addiction

It's probably easiest to understand this if we put it in more concrete terms.

Let's say we have a goal for an offender population. We want to help heroin-addicted adults to stop using heroin.

For any given person, there is a lifetime worth of history that led to their heroin use. We could spend a lifetime teasing all that out, and learning every single detail of their history, and making a comprehensive assessment of why s/he uses heroin and what we could do to try to get him/her to stop. But that's a tremendously resource-intensive approach, and we simply don't have the time or resources to devote to doing that for every single heroin-addicted human out there.

But when we look at the whole population of heroin users, we are going to start to see patterns in how people, in general, become addicted to heroin. These factors would include: untreated mental health issues, chronic physical pain, heroin-using friend groups, etc. So once we identify these general predictors, we can develop approaches that allow us to address those predictors for lots of people at a time. For examples:

- for people with untreated mental health issues, we can place them in mental health care facilities and help address those issues.

- for people with chronic physical pain, we can connect them witrh medical professionals or services that can help alleviate that chronic pain.

- for people with heroin-using friend groups, we can find ways to extract them from their social surroundings and help them get a fresh start.

The social-scientific process is going to help us identify these risk factors, create interventions, and assess the effectiveness of those interventions. It can also help us identify which interventions are most likely to be effective for which people, so that we can get people the help they need and not waste time or resources "helping" in ways that don't actually help very much.

That process of learning about issues, developing interventions, and determining effectiveness is what we call evidence-based practice, and is an important principle for corrections.

Evidence-based Corrections

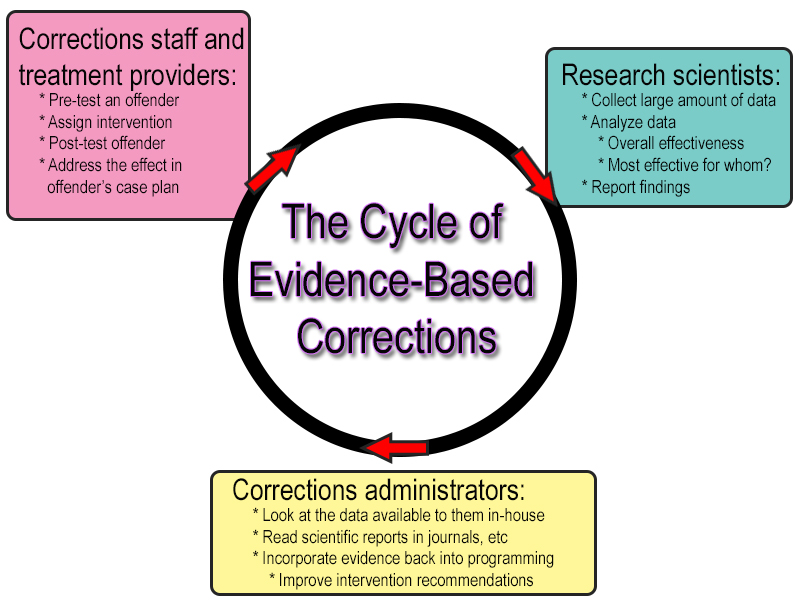

Evidence-based practice is used in all areas of corrections. It is used in institutions, in community supervision, and in treatment settings at all levels of security and across jurisdictions. The image below provides a general idea of the model of evidence based corrections, but every facility and organization will have its own specific approach.  This cycle of social-science-based practice allows us to get the most "bang for our buck" so to speak. The more we know about the nature of offending and the effectiveness of our interventions, the more rehabilitation can happen.

This cycle of social-science-based practice allows us to get the most "bang for our buck" so to speak. The more we know about the nature of offending and the effectiveness of our interventions, the more rehabilitation can happen.

The scope of evidence-based corrections

Many of our treatment approaches address offending behavior from a psychological foundation. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy- a widespread and well-supported psychological approach to offending- looks at the cognitive processes that can lead to offending. However, there are a lot of other ways that social-science contributes to corrections, outside of looking just at the psychology of offending. For example:

- Research on neighborhoods and neighborhood characteristics helps us understand how probationers and parolees face different challenges based on where they live.

- Research on race helps us understand and address the disproportionate minority representation in the criminal justice system.

- Research on gender helps us understand the unique challenges faced by female inmates and address the violence and aggressiveness created by the "tough guy" image of masculinity among male inmates.

- Research on behavioral ethics helps us understand how people respond to being in charge of other people and provide the professional training required for the challenges of supervision.

The list goes on. Overall, the main point is that there are lots of ways we can use the scientific method in a correctional context, so evidence-based corrections is a large and valuable part of modern correctional approaches.

Professionalism

One of the most famous studies on the prison context was the Stanford Prison Experiment, run by Dr. Philip Zimbardo in the 1960s. Zimbardo's experiment, as well as Milgram's obedience experiment and other similar studies, looked at how humans responded in situations where some people have authority over others. World War II and the Nazi regime ended in the 1940s, but our questions lingered; how did "normal" people become willing participants in the kinds of artocities we saw happening in Nazi Germany?

Zimbardo's experiment helped us understand that human beings don't have to be monsters to be contributors to monstrous social situations. Zimbardo's experiment- the guards and the inmates both- were college students. They were selected precisely because they were normal, and were randomly assigned to the guard and inmate groups. All of them were pretty normal, straightforward people. And yet, the whole thing was shut down in a matter of days. Inmates were experiencing panic attacks and other signs of distress. Guards were acting sadistically. Zimbardo himself says that he didn't really see how bad things were until someone from outside the situation pointed it out.

So what happened? To give a somewhat oversimplified answer: people aren't good at monitoring and moderating their own behavior in situations where they have power over other people and/or where they are functioning in a hierarchical authority structure. Milgram and Zimbardo both came to this conclusion.

We saw it more recently in the Abu Ghraib situation as well. The soldiers involved in Abu Ghraib were soldiers in the US military, which provides a fair amount of training. However, the Abu Ghraib personnel were trained for combat support, and were never trained in "internment and resettlement"- guarding detainees or prisoners. Also, the rules weren't especially clear about what was appropriate behavior in the detention context. So when the Abu Ghraib pictures hit the US media there was a fairly large popular uproar, and the soldiers themselves reported being caught completely off-guard by that. They had no real way to know what was or was not known by the US population in general, and felt they were doing what was being asked of them under the rules of enhanced interrogation.

Overall, the research tells us that human beings- not just "bad" human beings, but ANY human beings"- have a hard time keeping track of behavioral expectations and decision-making perspective in contexts where there is hierarchical authority and where people have power over others. That's why professionalism- the knowledge, training, and ongoing maintainence of occupational standards- is essential for corrections. Every single day our correctional officials are asked to function effectively and ethically in those very contexts. Professionalism allows correctional personnel to keep track of that problem, and at the same time to learn the best and most effective approaches for correctional supervision. Professional associations, professional standards, certification processes, continuing training and education, and all the other facets of professionalism are absolutely essential to a responsible and effective system of correctional supervision.

Exploring Resources

External Resources

External Resources

- The National Institute of Corrections' website on evidence-based corrections.

- https://crimesolutions.ojp.gov/: A clearinghouse for information on criminal justice-related evidence-based practices.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment website: Dr. Zimbardo's webpage on the prison experiment and the lessons learned from it.

- The American Correctional Association, the Americal Probation and Parole Association, and the American Jail Association: The websites for the largest US-based correctional professional associations.