CRIMJ250W:

Lesson 2: Theory and Criminal Justice Research

Theory and Criminal Justice Research

Criminology, as a body of knowledge regarding delinquency and crime as social phenomena, examines various theoretical perspectives on the correlates of deviant behavior. These theories, by themselves, are nothing more than ideas about the nature of such behavior and a rationale for addressing the root cause of criminal activity. What makes them useful tenets of social science (and thus part of a criminology course) is that these theories have been rigorously tested using the scientific method we will be discussing in this lesson.

In the discussion of common errors in native human inquiry, we noted that an idea or hypothesis by itself is an ex post facto hypothesis, or one person's subjective opinion about a phenomenon. What separates useful theory from ex post facto hypothesis is this testing using scientific principles. The Traditional Model of Science has four major parts: theory (or ideas), hypothesis building, observation, and data analysis. We'll go over those components briefly.

This scientific model is utilized, in some form, in every disciplinary field. The components of the model allow researchers to identify what information is to be collected, how the data collection will proceed, and what conclusions can be drawn from the data to refute, support and eventually modify the original theory that began the inquiry. In criminal justice research, The Traditional Model of Science is a continual cycle of investigation and inquiry that allows social scientists to refine and build upon the already existing knowledge base to try and answer issues related to deviant behavior and society's response to it.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to

- diagram, define, and explain the components of the traditional model of obtaining scientific information;

- explain the ancillary issues pertaining to the Traditional Model of Science; and

- differentiate between deductive and inductive logic.

Please complete the assignments and readings outlined on the course schedule for this week.

Theory or Idea

The first component of the model is Theory or Idea. A theory is defined as an organized set of ideas that generate conceptual relationships about social reality. Obviously, social reality is what the scientific model is trying to shed light on. Our theories are our best guesses as to that reality, and as guesses have no empirical weight to them until they are scientifically tested. The first stage in this process boils down to clearly establishing the nature of the relationship(s) between social phenomena.

Let’s look at Shaw and McKay’s theory of Social Disorganization from 1942 as an example. Shaw and McKay, sociologists of the famed Chicago School of the 1960’s, were two of the first criminologists to geographically map criminal offenses. They used a pushpin map to locate serious offenses in the city of Chicago for one year and found pockets of concentrated criminal activity in certain city zones or neighborhoods. Now any beat cop or observant city resident could have told you what parts of the city were "bad" or "crime prone," but Shaw and McKay wanted to explain why those zones were so crime-riddled. They noticed that these crime-heavy zones were also areas of frequent population turnover -- they were characterized by run-down rental housing, poor quality of life, businesses which catered to a transient population, and general disorder. Shaw and McKay believed that these were symptoms of an overall breakdown in neighborhood informal social controls; the transience meant neighbors didn’t get to know one another well, 'strangers' were not seen as strangers in the neighborhoods, and people kept to themselves waiting until they had the resources to move to a more attractive community. The two scientists characterized neighborhoods of this type as "disorganized," thus forming the basis for their theory of Social Disorganization -- Conditions of disarray lead to higher levels of serious criminal activity. This was the notion that they set out to test scientifically.

Explore More!

- Social disorganisation theory from Wikipedia -- a summary of the theory

- Clifford R. Shaw and Henry D. McKay: The Social Disorganization Theory -- explanations of spatial dynamic with the concentric circles and zone of transition idea

Hypothesis Building

In order to test a theory, one must first put forth a specific hypothesis that can be tested in a scientific manner. This second component of the Scientific Model is Hypothesis Building and sets forth which aspects of social reality are to be evaluated.

Shaw and McKay's theory contained two major concepts: disorganization and serious criminality. One of the first things to recognize about hypotheses is that they come about on two distinct levels: abstract and concrete. A conceptual hypothesis is abstract; that is the terminology used to describe social reality are abstract labels that encompass many different facets. For example, if I asked you to walk through a "bad" neighborhood and point out "disorganization," you might identify abandoned buildings, certain businesses (like pawnshops), litter in the streets, etc. All of those things are concrete representations of the concept 'disorganization.' In other words, they are concrete indicators of abstract concepts. Later in the course we will be looking at conceptualization and operationalization in great depth, but for now, in our discussion of the traditional model of science, you should simply understand the difference between the two. So for Shaw and McKay's theory of Social Disorganization, the hypothesis could be as follows:

- Conceptual Hypothesis (Abstract): As a neighborhood becomes more disorganized, the potential for serious criminal activity markedly increases.

- Testable Hypothesis (Concrete): As rates of population turnover increase, the number of arrests for Part I index offenses will increase proportionally. See this hypothesized correlation between rates of population turnover and the number of arrests in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Testable Hypothesis Example

Notice that I called the latter hypothesis testable. This means that the hypothesis has put forth indicators of the concepts that are measurable, and thus testable scientifically. We are now at the stage of the scientific process where empirical observations can be made: we can get data on how frequently residents move in and out of a neighborhood, we can readily get arrest statistics from the police department for the various zones/neighborhoods, etc.

Observation

This gathering of data is the third major component of the Traditional Model of Science: the observation stage. Whether we collect measurements using a survey, make observations firsthand, or use data that already exists (like police records) we are gathering empirical evidence that will either support or refute our hypothesis, and by extension, our theory. Shaw and McKay, using police reports, tracked juvenile arrests made by the Chicago Police Department over a period of several years and mapped the home addresses of those arrested juveniles on a map of the city to pinpoint where concentrations of juvenile delinquents resided (i.e. what neighborhoods) and where their crimes were being committed (i.e. inside their own neighborhoods or elsewhere).

This gathering of data is the third major component of the Traditional Model of Science: the observation stage. Whether we collect measurements using a survey, make observations firsthand, or use data that already exists (like police records) we are gathering empirical evidence that will either support or refute our hypothesis, and by extension, our theory. Shaw and McKay, using police reports, tracked juvenile arrests made by the Chicago Police Department over a period of several years and mapped the home addresses of those arrested juveniles on a map of the city to pinpoint where concentrations of juvenile delinquents resided (i.e. what neighborhoods) and where their crimes were being committed (i.e. inside their own neighborhoods or elsewhere).

Data Analysis

How does evidence support a theory? Well, the observations must be examined to determine if the evidence matches your initial reasoning. This is the fourth and final part of the process: data analysis.

Data analysis is used to assist in drawing conclusions based on the data that has been collected. Most often we associate data analysis with statistics, but that does not necessarily have to be the case -- data analysis can be textual as well. After conclusions are made the theory is either given support, modified, or refuted altogether.

Note that as social scientists we can never “prove” our hypotheses to be true or false. Because we conduct research that has a certain level of probability inherent in our observations, there is always room for error. It is more accurate to talk about evidence to support or refute a hypothesis.

As we know from history, Shaw & McKay's ideas were supported initially, but further examination led to modifications of their theory, and eventually the theory fell out of scientific favor as more individual-level theories (like strain, learning, and anomie) were used and seen to better explain offending. And herein lies perhaps the most important idea relative to the Traditional Model of Science: it never ends.

Wheel of Science

The Model is sometimes also known as the "Wheel of Science," because the process is ongoing. Once conclusions are made about a theory, the theory is tested again and again. The more times it stands up to scientific rigor, the more support it gets within the discipline of criminology. And also weaker theories are exposed, and usually either change form or fall out of favor. So structurally, we often see the Traditional Model of Science diagrammed in the form demonstrated above. The process keeps going around the "wheel," continually testing ideas as to their veracity to hold up in the "real world." We test theories in different contexts, at different times, and with different subjects, all in an effort to see if our ideas about social reality are supported scientifically. If they are, then our ideas are seen as valid until shown otherwise. Notice I didn't say proven. Proving things is not a part of social science, as will be explained in the next chapter. Ideas should not be seen as valid until they have gone through this process. It is the scientific process which separates speculation from empirical fact.

Ancillary Issues Pertaining to the Traditional Model of Science

By this point you’ve probably realized that our focus in this course will be upon formulating hypotheses, and the subsequent scientific methods used to test those hypotheses. Within this framework of the Traditional Model of Science are a few ideas that need to be addressed prior to delving further into the specifics of the Model. A number of these terms you've undoubtedly heard before, but perhaps like most people, never really gave much consideration to their meaning. Below is a discussion of these ideas and, hopefully, some perspective will be given to how these ideas fit within the scientific lexicon.

There are two ways to go about producing knowledge scientifically within the Model of Science: deductively and inductively. While these terms represent different perspectives on how one starts inquiry into a topic, the differentiation is not overly important, as you’ll soon see. Deduction and induction simply refer to how one starts the inquiry process. In terms of the Model of Science, the reference is to where the process begins. Deduction is also commonly known as theory testing. In the example above of Shaw & McKay, they used deductive logic in testing their ideas about disorganization and crime.

There are two ways to go about producing knowledge scientifically within the Model of Science: deductively and inductively. While these terms represent different perspectives on how one starts inquiry into a topic, the differentiation is not overly important, as you’ll soon see. Deduction and induction simply refer to how one starts the inquiry process. In terms of the Model of Science, the reference is to where the process begins. Deduction is also commonly known as theory testing. In the example above of Shaw & McKay, they used deductive logic in testing their ideas about disorganization and crime.

As previously stated, Shaw and McKay were greatly influenced by Burgess and his concentric zones, and Burgess's model led them "to the conclusion that neighborhood organization was instrumental in preventing or permitting delinquent careers" (Lilly et al., 41). They ventured out to find if Burgess's model held up; that the highest rates of crime would be in the zone of transition, and would decrease outward. Shaw and McKay studied juvenile court statistics and confirmed the predictions by Burgess.

To deduce is to begin with a specific theory or idea, then use general observations to test that theory. Thus, deduction always begins at the "top" of the Wheel of Science with theory. Inductive logic, by contrast, begins at the "bottom" with general observations which subsequently become a specific theory or idea. Many anthropologists conduct their research in this way -- observing a culture and then drawing specific conclusions from the observations made. The work of Margaret Mead is perhaps one of the best examples of inductive reasoning. The Margaret Mead Biography offers a summary of her work.

While the distinction is procedural, it becomes a moot point after the scientific process has started simply because, for example, once a theory is developed from observation, it must then be re-tested deductively. And after an initial theory is modified on the basis of observation, it is re-tested inductively. Therefore, because the scientific testing process is continual, the system of logic chosen only indicates how enquiry was begun. Some scientists prefer to start with a 'clean slate' inductively; others prefer to start with a previously held idea or assertion. Either method is fine, as long as the scientific process is utilized correctly.

As grade-schoolers, we were introduced to certain scientific laws that have become second nature to us, like the Law of Gravity. In social science there are no laws, or absolutes, because our subject is human behavior, and human beings are not constant. This idea, in my opinion, makes our field of study that much more challenging. While the chemist knows that two hydrogen molecules and one oxygen molecule will always produce water, we can never say with 100 percent certainty that a social factor will always produce a particular outcome. Therefore, we seek to establish patterns of behavior applicable to groups, and tend to shy away from trying to predict individual behavior. And as an aside: don’t confuse scientific laws with laws as legal statute that we are familiar with in criminal justice. Statutory law is not constant, obviously, laws can and do change – they are a byproduct of human behavior.

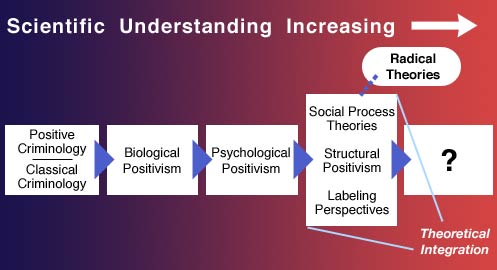

A paradigm is best defined as the conventional wisdom or general frame of thinking related to a time period. Paradigms define the scientific climate of the time within which the traditional model of science operates. For example, early criminologists focused on biological determinants of criminal behavior and the science that was undertaken by the Positivists reflected the notion that criminal behavior was thought to be based in human physiology.

As the thinking changed, a paradigm shift occurred that led criminology to focus on psychological explanations of crime, and then social factors. Presently we are operating in the paradigm which views criminal behavior as a product of the social milieu, but we are braced for another shift in paradigm. The next paradigm will undoubtedly incorporate what we’ve learned from the field of genetics to aid in explaining the social context of deviant behavior. As you can see, the scientific enterprise drives the overall perspective or paradigm; the paradigm shifts when science becomes more advanced and challenges the prevailing wisdom.

Figure 2.1: Paradigm Shift in Theorietical Criminolog

Foundations of the Scientific Enterprise

The foundations for the study of human behavior have been in place for as long as researchers have cast an eye toward the social world. First and foremost, the enterprise is logico-empirical, meaning that it is based upon logic or rationality and scientific observation. As we've previously explored, theory is the basis for developing testable relationships that are based on logical, explorable line of thought. As such theory does not address 'what should be or what ought to be,' rather the theory states 'what is,' in an objective manner. Remember -- science cannot address value judgments, as values are not rational and therefore scientifically defined as illogical.

The three Foundations of the Scientific Enterprise are as follows:

- Theory

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

These three are analogous to the components of the Traditional Model of Science, as research methods encapsulate both hypothesis building and observation. But what the 'Foundations' do is put forth explicitly what must be involved for information to be considered scientifically valid. All of the steps within the scientific process are conducted with adherence to these Foundations in mind -- any deviations or missteps harm the validity of the final product. We will be covering those steps in the scientific process throughout the course.

Social Regularity

But there is also one "unofficial"foundation that must be discussed at this time, before we get more into the particulars of social scientific research design illustrated in Figure 2.2. What is referred to here is the idea of social regularity, the notion that the social world has some pattern and regularity to it -- that not all human behavior is chaotic or random.

In order for us to study behavior in a scientific fashion, this idea must be assumed to be fact. You'll remember that we said that social scientists look to establish patterns and trends among groups of people, but in the end behavior is ultimately the free choice of the individual (a person's "free will"). For example, if you are to be at work at 8:00, Monday through Friday, the pattern is that you'll arrive at work those days sometime around 8:00. But there may be a day when you aren't at work, for whatever reason. One of those reasons may simply be you've chosen to take a day off. Social Science cannot 'predict' these seemingly random choices that people make, therefore our discipline has come under attack from the so-called hard sciences (such as chemistry, physics, and biology) because we don't have absolutes, and therefore there is no way of knowing if our conclusions are truly valid. In the end, we've settled for not being able to produce absolutes, and to rely on illustrating patterns of behavior in a probabilistic sense. For example, we say students attend class 80 percent of the time. This illustrates the behavior, but doesn't define it as absolute or without variation.

And as a final note on this: while trends and patterns of aggregate (group) behavior can aid in predicting individual behavior, any conclusions about individual behavior based on aggregate patterns should be viewed with extreme caution. There is a far greater chance of being wrong when predicting an individual's behavior because the"free-will factor" is so much greater than within a group, and more difficult to account for.

In the second section of the course, i.e. structuring criminal justice inquiry, we will examine how scientists use social regularity to frame their research in a deterministic sense.