CRIMJ408:

Lesson 2: TIntrodcution to Police Organization

Introduction

This lesson tracks the history of police administration and management from its early conception to the present day. The chief architects of police administration and management derive from both practitioners and academics, and presented here are the leading schools of thought, including public administration, business management, and police management. At present, police management tends to be a blend of the historical schools of management. Students should be familiar with the various schools as well as their historical roots and major ideas.

Additionally, this lesson discusses the complexity of police organizations. Structural complexity is more common in larger departments. Larger departments have more officers to supervise, so there may be a longer rank structure than in smaller departments (called vertical complexity). For example, an officer in the Baltimore Police Department reports to her sergeant, who reports to the lieutenant, who reports to the captain, who relays information to higher ranks, whereas an officer in a smaller police agency might report directly to the chief. Another example of the longer rank structure is the Los Angeles Police Department. Here is a graphic of their police ranks from the commissioner to the captains; keep in mind there still are other supervisory ranks between the captains and the officers on the street: http://assets.lapdonline.org/assets/pdf/org%20chart.pdf

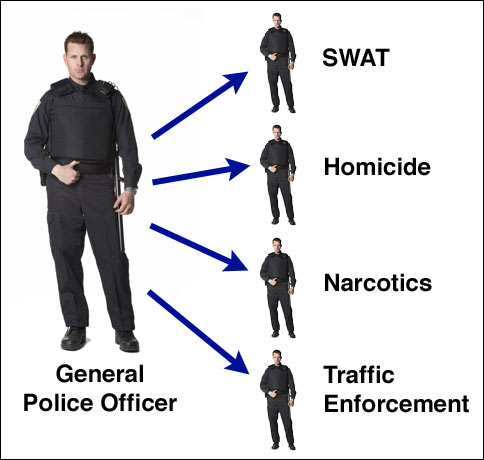

Larger departments have more employees who can specialize (called horizontal complexity) into specific task areas, such as gang units, gun crimes units and child trauma units. On the contrary, smaller police departments often require officers to be generalists, having a wide range of skills and abilities.

Organizational complexity can vary by geography, too (spatial complexity). We will discuss each of these and more in this lesson.

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to:

- review Peel’s Nine Principles;

- define police organization;

- distinguish between organizational theory and organizational behavior;

- analyze the concept and characteristics of the police subculture;

- describe ways in which organizational complexity varies among departments;

- detail organizational control; and

- identify police organizational tasks.

Please complete readings and assignments as listed on the course schedule.

The Industrial Revolution and Traditional Management: 1750-1900

It is important that students understand how the Industrial Revolution changed English society, and by extension, the rest of the world. Until the revolution, society was much more agrarian. With the industrial revolution came the prospects of making money, which at the same time agriculture came under stress.

This video from History.com provides a great overview of the age.

Cities became a magnet for people fleeing the countryside and seeking employment in the major urban centers. With the sudden rise in population, crime and disorder became a byproduct of the Industrial Revolution. Because of the growing intolerance of disorder, cities needed a professional police force.

Present day policing has as its foundation the ideas of Henry Fielding and Sir Robert Peel of early nineteenth century London. The Industrial Revolution had an enormous impact on rural life in England because urban industries offered the promise of a steady income and stability. From the farms a great influx of people moved to the major urban centers in search of a better life. But instead of fulfilling their dreams, they became part of a nightmare of poverty, unemployment, and crime. This caught the attention of Sir Robert Pell, who was mainly responsible for the legislation passed in Parliament entitled The Metropolitan Police Act. The main duty of this policing organization would be crime prevention and protection of property—not law enforcement. In fact, early police ran soup kitchens and housed the homeless, located missing children, performed inspections, and more. Only recently with the movement to "professionalize" police has policing become synonymous with "law enforcement".

For a great summary of the history of police, see Eric H. Monkkonen (1992). History of Urban Police. Crime and Justice, 15, 547-580.

The Nine Principles of Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel was instrumental in having the Act for Improving the Police in and Near the Metropolis (the Metropolitan Police Act) passed in the English Parliament in 1829. Peel had a specific vision as to the principles under which the police should operate. The nine principles that he penned nearly 200 years ago are just as important to proper police operations today as they were in early nineteenth-century London.

- The basic mission for which the police exist is to prevent crime and disorder.

- The ability of the police to perform their duties depends on public approval of police actions.

- Police must secure the willing cooperation of the public in voluntary observance of the law to be able to secure and maintain the respect of the public.

- The degree of cooperation of the public that can be secured diminishes proportionately to the necessity to use physical force.

- Police seek and preserve public favor not by catering to public opinion but by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to the law.

- Police use of physical force to the extent necessary to secure observance of the law or to restore order only when the exercise of persuasion, advise and warning is found to be insufficient.

- Police, at all times, should maintain a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and the public are the police, the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

- Police should always direct their attention strictly towards their functions and never appear to usurp the powers of the judiciary.

- The test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with it.

Sir Robert Peel

Police misbehavior can usually be found to violate one or more of Peel’s nine principles. Perhaps more importantly, we have allowed our police to stray far beyond the basic mission of prevention of crime and disorder first laid out by Peel. Indeed, in most instances, police no longer look like police officers because they have taken on a more militaristic look. For example, the dress shirts, tie, dress slacks, and shined dress shoes have given way to a different look. Many of today’s police dress in dark blue or black wash and wear pants and shirt, with some police departments choosing a one-piece jumpsuit. Shined dress shoes have been replaced by either dark tennis shoes or laced up paratrooper jump boots and bloused pants. It is now common to see police officers attired in assault gear complete with helmet with automatic assault weapons, with trigger finger at the ready.

Along with revised uniforms has come a revision of the vision of policing. Police officers no longer see themselves as members of a "helping profession," as conceived by Sir Robert Peel, but instead view themselves as “law enforcers." Whereas law enforcement had always played a minor role in policing, the shift in paradigm toward "enforcement" can be seen in the many martial metaphors in current use: “War on Crime,” “War on Drugs,” and now “War on Terror.” This is not their fault but rather ours. We have placed upon our police ever increasing demands, making them responsible for social problems, which are beyond their control. The latest increase in responsibility has come by classifying police as the first line of defense against acts of terrorism. Little wonder they have become increasing militaristic in both uniform and thought. Reversing police militarism will not be easy because it has become so well entrenched and is reinforced by the constant drumbeat of “War on Crime, “War on Drugs,” and “War on Terror.” Unless serious effort begins to reclaim policing, Peel’s Nine Principles will never become a reality.

Reference

Dempsey, J. and Forst, L. (2008). An introduction to policing. Belmont, CA: Thompson-Wadsworth, 7-8.

Concept of Organization

The Northwestern Traffic Institute emphasized two characteristics of organization as part of their basic definition: the mechanical/structural approach and the humanistic approach. The mechanical/structural approach functions by means of organization and subdivision of action to obtain economy of effort by means of specialization and coordination of work, in that way leading to unity of action. It emphasizes the mechanics or physical aspects of organization.

On the other hand, the humanistic approach can be viewed as separating and grouping work to be accomplished into different jobs, and circumscribing the traditional relationships between personnel occupying those positions. This concept highlights the personnel through whom all work is done.

German sociologist Max Weber laid out the blueprint that has become the foundation for all modern bureaucracies, including policing organizations. At its core, any modern bureaucracy is dependant on having a money economy to pay salaries. It must also acquiesce to the view that recompense be rooted on merit and work output instead of the circumstances of birth.

Police Organizations Today

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the United States has over 18,000 state and local law enforcement agencies, which employ 765,000 sworn officers and another 368,000 non-sworn civilian personnel. Police leaders must manage these employees as well as address their organizational goals, which typically include reducing crime and building relationships with the community.

Many of us think of big city agencies when we think of police organizations - agencies that are "intentionally structured for the purpose of achieving one or more goals" (Giblin, 2017, p. 4). While the bulk of police officers work at larger departments, it is important to remember the variation among departments. In fact, 49% of state and local policing agencies have 10 or fewer full-time officers. We must keep in mind that policing is predominantly rural and small-town, with several large agencies in big cities (Reaves, 2014).

Organizations include three components:

- People: individuals or groups who pursue a collective purpose;

- Structure: divide and coordinate work; and

- Durability: operate over time (Giblin, 2017).

Despite the variation among policing agencies, there is similarity in that they all share these three components.

Macro v. Micro Study of Organizations

At the macro-level, the study of organizations (e.g., structure, practice) is called organizational theory. For example, Dr. Jennifer Gibbs, one of the faculty in Penn State Harrisburg's School of Public Affairs, and an undergraduate Criminal Justice student wrote a manuscript describing the appearance policies of all state policing agencies in the United States. (The manuscript is under review at a peer-reviewed journal.) They were interested in the difference among various tattoo policies, ranging from not permitted at all to permitted with some exclusions (such as no face or neck tattoos) to no policy at all. Here, organizations were compared with one another.

At the micro-level, the study of individuals within the organization (such as police leaders) is called organizational behavior. Another research project led by Dr. Gibbs, along with Dr. Ruiz, studied withdrawal of applicants to a large policing agency in the northeastern United States. In this project, undergraduate and graduate research assistants called applicants who withdrew within the last seven testing cycles to ask why they withdrew their application, among other questions. Here, individual applicants were grouped and then compared with one another.

References

Giblin, M. J. (2017). Leadership and management in police organizations. Los Angeles: Sage.

Reaves, B. (2011). Census of State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/csllea08.pdf

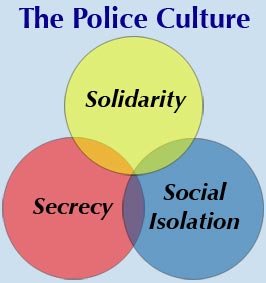

The Police Culture

Culture, existing in most levels of society, may be defined as "the set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution or organization." This would seem to speak to the characteristics of a society in general. However, police have often been said to be a subculture—a part of but separate from the whole. Subculture has been defined as "an ethnic, regional, economic, or social group exhibiting characteristic patterns of behavior sufficient to distinguish it from others within an embracing culture or society." This definition seems appropriate when attempting to characterize a police organization. The police subculture has been characterized by three major norms: secrecy, solidarity, and social isolation.

Secrecy – Police officers involved in many sensitive operations and investigations often require secrecy. However, the issue of secrecy in policing far exceeds that which is necessary for normal operations. Secrecy in policing often extends to keeping silent about police deviant and even criminal behavior. Clearly, in society an informer or a rat is looked down upon. In policing, it is taken much more seriously. For example, if a police officer were to inform on another officer involved in criminal behavior, the informing officer would be viewed as a stool pigeon even though she or he did what his or her oath of office required.

Another crucial element in secrecy involves the invaluable reputation of an officer who may have allegations of misconduct lodged against him/her. Police departments are often criticized for refusing to reveal the names of addresses of officers accused of department or criminal violations. Because this practice has become so common placed in news reporting, little care is given to the impact this can have on the family and friends of the officer or the officer's future prospects of career advancement. This writer experienced such an incident in the beginning of his career, but was cleared of any wrongdoing. However, that incident haunted his career and was mentioned on the night of his retirement.

Solidarity – Most police officers believe that the only person to come to his or her aid will be another police officer. Each officer is acutely aware of his or her human side and the potential for complaints from the public or some violation of departmental rules and regulations. Under such circumstances, fellow officers are expected to come to the aid of the officer(s) in trouble. The "us v. them" mentality not only refers to the adversarial perception of police v. public, in which most police sincerely believe, but also extends to within the police organization itself—in that line officers do not trust police administrators. This distrust was the driving force for the modern era of police unionization, which began in 1969 with the Patrolman’s Association of New Orleans (PANO).

Social Isolation – Because of the nature of their work, police officers feel isolated from the public, an isolation partly self-imposed. Many police officers see what they do as "asshole control," with a perception that they are pitted against the public in a "them vs. us" contest. They also believe that the general public dislikes them, though research indicates that the public overwhelmingly feels positively toward the police. This tends to drive them into a more closely knit group. This cohesion is magnified by the requirements of the job which include, but are not limited to shift work, lack of holiday time with the family, and answering the call to duty during times of emergency with most other workers are with and caring for their families.

Reference

- http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/culture

- http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/subculture

- Van Mannen, J. (1978). The asshole. Policing: A view from the street. Peter Manning and John Van Mannen (Eds). Santa Monica, CA: Goodyear 221-238

The Police Subculture - Women and Minorities in Policing

The entry of women into policing appears to have come about due to a shortage of men to staff open positions. The first women, with the title of matron, were hired by the New York Police Department (NYPD) in 1888 to assist with the Great Blizzard. But, not until 1975 was the first “female patrol officer” hired.

Research on women in policing has addressed assessing their

- effectiveness,

- attainment of rank,

- foray into specialized areas,

- impact of stress,

- policing styles,

- management of intense situations,

- and those areas where they surpass their male counterparts.

Outside of the United States, progress of women into policing came on the heels of reconstruction such as what occurred during the reconstruction periods of the two World Wars as well as times of nation building such as the post colonial period in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the developing democracies of Eastern Europe and South America. Women began entering uniformed policing in significant numbers in the early 1980s. Traditionally, the policing occupation has been mainly the province of white males. Not until the late 1960s and early 1970s did minorities began to enter policing in substantial numbers. Grudging acceptance of women came about only after considerable harassment and denigration. As a platoon commander, this writer was not one who welcomed women into policing ranks. However, women demonstrated that they possessed many of the qualities sought by platoon commanders. They were punctual, neatly dressed, well-spoken, and probably two of the most important qualities; great report writers and they tended to generate far fewer citizen complaints than their male counterparts. Many women rose through the ranks to command positions, and research demonstrates they were and are well-suited and held in high regard by nearly all departmental members.

The experience of black officers was first chronicled in the groundbreaking book, Black in Blue (1969), which spoke of how black police officers were accepted under the work situation but excluded from the off-duty social scene of white police officers. Also, barriers had been erected to keep blacks out of the detective and upper ranks of policing.

This was true for all minorities but in particular female minorities. Minority males had a much greater level of acceptance by white officers. Minority females, on the other hand, were not only looked down upon by white males but also male police officers of their own minority group. It was believed that female officers could not meet what many viewed as the demanding physicality of policing. Females proved them wrong. Research conducted on the performance of females as police officers has been positive across the board. Females were found to have had the same performance rates of their male counterparts and established better rapport with citizens. Finally, they also generated much less in the area of citizen complaints, which did not go unnoticed by police supervisors and administrators.

Gays and Lesbians in Policing

The late 1960s and early 1970s also witnessed the open entry of members of the gay and lesbian community into policing. Just as females were viewed as unsuitable to manage the demands of policing, so were gay and lesbian officers. Beyond sexism, many police officers of all stripes were challenged by their own homophobia, and gay and lesbian officers had their own special rite of passage into policing to experience. However, time did for them the same as for female police officers. Gay and lesbian officers demonstrated to the straight officers that they could do the job. This won over, in some circles, grudging acceptance to their presence in policing.

This writer witnessed first-hand the reaction to two gay police officers assigned to the French Quarter in the late 1960s and early 1970s. One officer was open concerning his sexual preference, but the other was not. For all of the officers working in that district, about 70, the openly gay officer was accepted because everyone believed he could be trusted to back other officers be it coming to their aid or "on paper." The other officer who was not open was not accepted because it was believed that he could not be trusted. Straight officers did not care about the sexual preference of the officers, but rather whether or not they could be trusted. In that sense, many urban police departments were operating on a "don't-ask-don't tell" basis decades before the US military.

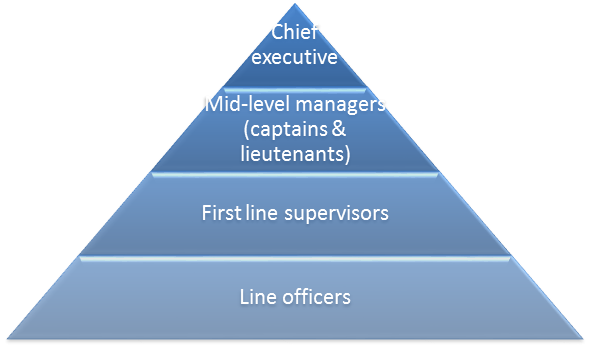

Vertical Colmplexity

Vertical complexity refers to chain of command or the "scalar principle". Chain of command establishes a clear line of authority from the chief executive of the policing agency to all employees under him/her. Typically, communication flows downward: the chief gives and order and everyone under him/her is expected to carry it out. Imagine a pyramid structure where authority lies at the top; the chief executive makes the decisions:

The pyramid may not always look like a perfect triangle. Consider Figure 2.1 on page 22 of the Giblin textbook. The pyramid can have a wide base, with many officers and few leaders; it can be a generally wide pyramid when there are many mid-level managers; or it can morph with considerable weight at the top when there are many top executive leaders with few mid-level managers. Either shape it takes, the pyramid structure suggests top-down communication, where leaders make decisions for subordinates to implement.

One exception to the top-down communication rule is community policing. The community policing movement attempted to upend the decision-making process, giving line officers on the street more discretion to solve community concerns, as officers on the street arguably are more familiar with the intricacies of their assigned neighborhoods than further removed administrators.

Sometimes, communication can flow upward, with line officers communicating to their sergeants, who relay information to their lieutenants, who share details with the captains and so on until the chief executive is informed. In this way, the chain of command can provide a two-way street for information.

Aside from communication, there are several unofficial hierarchies present in policing organization, including those based on skills, rewards, status and seniority.

References

Cordner, G. W. (2016). Police Administration (9th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Horizontal Complexity

At one time the majority of police officers worked in districts or precincts answering calls for services. However, now police recruits expect to come out of the police academy and go straight into a specialized division; being "just" a police officer is no longer fashionable. Police personnel want to specialize in burglary, homicide, SWAT, narcotics, traffic enforcement, or in a host of other areas. In fact, police officers will sometimes wait at the scene for another arriving officer to handle simple incidents such as a traffic accident, theft, burglary, or other cold calls that do not require specialized skills in report writing or investigations. Just as centralization was the buzzword for the early twentieth century so specialization is for beginning the twenty-first. And now as decentralization is taking hold, many believe that the age of The Uniformed Generalist will not be long in coming.

There seems to be a disconnect in thinking with regard to specialization. For example, how are specialized personnel to get the experience and training needed to function properly without the wide-ranging experience of a generalist? In the field, of course service is as line officers. In fact, police officers must be generalists. However, good arguments exists for some specialization and organization of departments into specific divisions, primary among these being that of control. Some personnel must be allocated by bureau or division to address specifics in a certain category of police problems. Second, priorities must be identified and work must be done in an organized manner. Because of the wide range of obligations given most police agencies, the commander of a division and the chief in charge of all divisions can set priorities. Last, specialization is thought to lead to expertise, and the police agency receives the benefit of efficient, knowledgeable experts by organizing according to divisions.

As time goes on, assigning the same officers to the same type of responsibilities means that these officers are the most current on information concerning these specialized problems. When specialization goes too far, communication disintegrates between divisions and individual commanders begin empire building, as one tries to outdo another in competition for perceived glory and resources. This is a common occurrence between the patrol and detective divisions.

Whereas line officers are closely supervised, expected to control the crime scene, and report the crime to the detective division, detectives are expected to give the reporting officers credit for their work and follow up the crime with analysis of investigations. However, this is not commonly the case. Over time, line officers can become jealous of the status and control that detectives enjoy, recognizing themselves as being the first on the scene but the last to receive credit and praise. Truth be told, nearly all detectives believe and act as though they are superior and neglect the patrol officers. Police administrators must be aware of these tendencies in all divisions and take consistent steps to improve communication.

Listed below are principles that can lead to administrative improvements:

- Tasks for all officers must be grounded on the belief that the job should provide new challenges and lead to the acquisition and development of professional skills;

- The optimum officer should occupy the job based on ability, credentials, and track record;

- Certain specialists are necessary but the number of specialists and their areas of specialization should be kept within reason;

- From time to time, each department must review the number of specialists in the formal organization and the need for their existence.

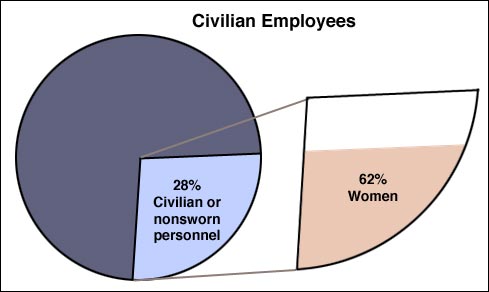

Civilian Employees

The Uniform Crime Reports state that civilian or nonsworn police personnel make up about 28% of the workforce for police departments in the United States and 62% are women. Most police administrators, more concerned about public image than the reality of the policing occupation, have been replacing uniformed police officers with civilians in the hope of budget savings and appearing progressive. The increasing use of civilian specialists positions, with fairly high salaries, resulted in few savings in the budget.

The findings of Heininger and Urbanek (1983: 205) suggest that using civilians may not lead to cheaper police protection, that using civilians probably do not "displace" sworn officers, and that there is no apparent relationship between civilians and either quality of police protection or the risk of danger which must be assumed by sworn officers. These conclusions are more interesting in the light of secondary findings, which show that

- "real" police salaries are down;

- police departments command a diminishing portion of the municipal budget "pie" while . . .

- both municipal expenditures and personnel levels rose sharply.

Civilian personnel are now being used in sensitive position in records, dispatching, computers, and increasingly in making judgment call that will affect the department and sworn personnel. But this “window dressing” has come with a price. It fails to recognize that police officers get “used up” in the field. The long and erratic hours, and constant exposure to low levels of stress over prolonged periods have a direct effect on the mental and physical health of police officers. It also fails to take into account those officers who become chronically ill or injured on the job to such an extent that they cannot return to street duty. Under the current rubric, these officers would either be forced out of the department or given a disability pension. Either way, this is extremely shortsighted because many of these officers do not want to sever contact with policing. What is more, these officers possess a wealth of experience that would be tossed in the waste bin. These officers are prime material for dispatchers, complaint operators, crime scene technicians, records work, and many other positions. Indeed, it would make good sense to continue to use the experience and dedication of these officers who have made the sacrifice of their physical and mental health for our safety.

Spatial Complexity

Spatial complexity refers to the geographical spread of a police agency. Consider the Village of Barker in Niagara County, New York. According to the 2010 US Census, Barker had a population of 533. The entire village is a beat. We could say that the Barker Police Department is not spatially complex.

In contrast, big city police agencies are divided into districts and beats. New York City Police, for example, are divided into precincts and sectors within those precincts to serve its 8.5 million residents. (How many villages of Barker could fit in New York city?!)

Barker and New York City represent two extremes in policing. However, there are many size departments in between with varying levels of spatial complexity.

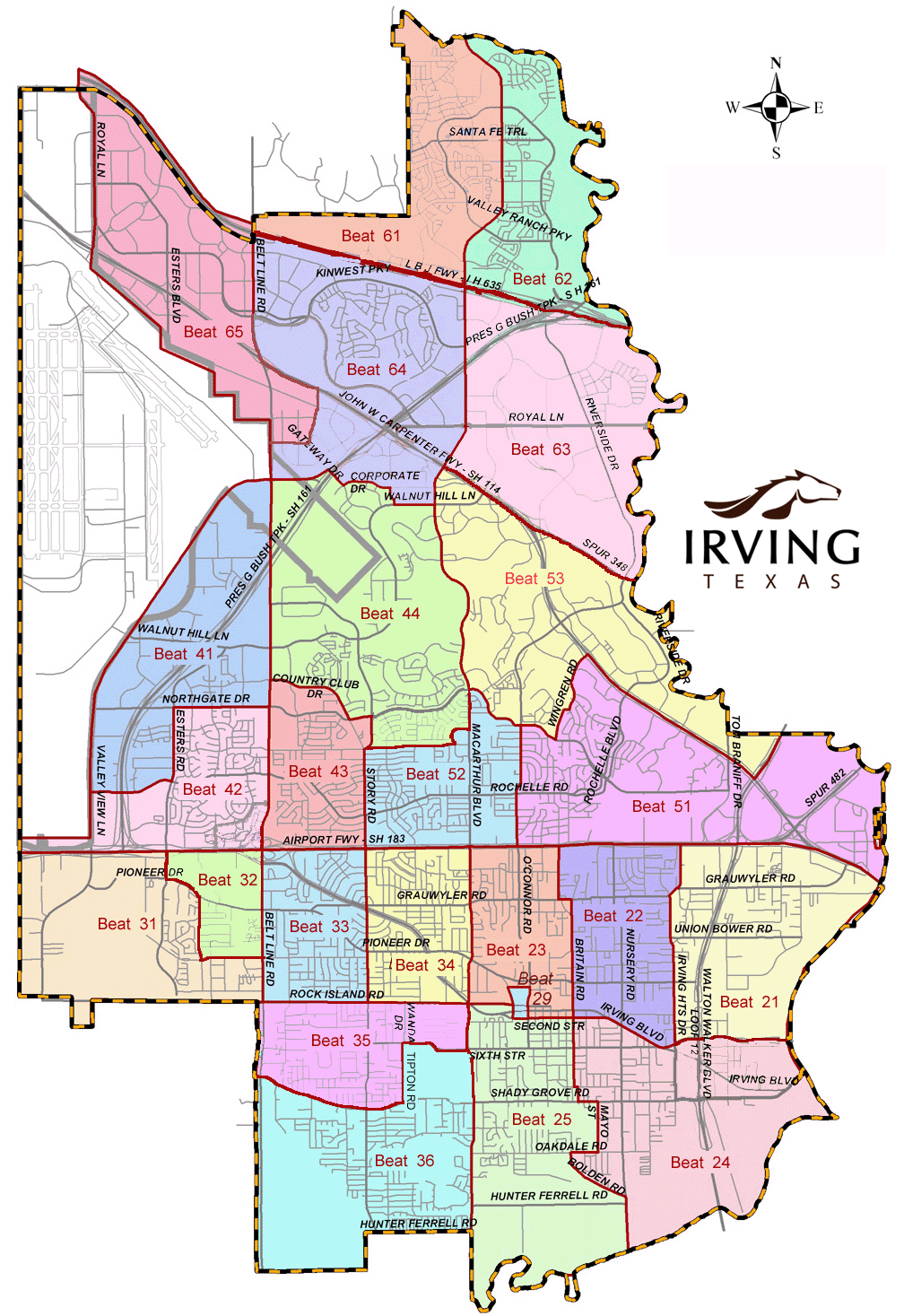

The map below depicts the beat map for the police in Irving, Texas, who serve around 238,000 residents. (Beat Map can be accessed online on Irving Police website).

Another example of varying spatial complexity is the city of Chesapeake, Virginia:

To see what each beat looks like, visit the Chesapeake, Virginia Police Department website. Click on each beat to see how populated it appears to be. Do some beats seem to be more populated with businesses and residents than others?

Organizational Control

Chain of Command

The activities of police agencies must be coordinated. One key organizational principle of control is chain of command. Chain of command "establishes formal lines of communication within a police department" (Cordner, 2016, p. 116). We reviewed chain of command when discussing hierarchical complexity, where communication typically flows downward from the top executive (i.e., the commissioner or chief) to the mid-level managers to the patrol officers. Bypassing the chain of command can have dire consequences. For example, if a chief gives orders directly to patrol officers without informing their immediate supervisors (e.g., sergeants, lieutenants), the supervisors are unaware of what the officers are doing and, worse, their authority is undermined. Patrol officers may think the chain of command is unnecessary and bypass it, as well. This would be chaotic and counter to the goal of organizing the agency!

Unity of Command

Unity of command means that every employee has one and only one supervisor. Have you ever had two supervisors who give you conflicting directions? Which do you follow? What will happen when the other supervisor learns you disregarded his/her directions? Bad things, right? Taking orders from more than one supervisor can be confusing at best, but often is frustrating and dangerous. Unity of command indicates that the patrol officer receive orders from the sergeant, who receives orders from the lieutenant, who receives orders from the captain, etc. The orders flow down the chain of command. This helps to keep a police agency organized.

Unity of command is not always as perfect as described here. In the 24-hour policing agency, sometimes the sergeant has the day off or has an alternative assignment. Considering this, Cordner (2016) recommends two adjustments to the unity of command principle:

- "it must be clear to employees which supervisors have the authority to command them under what circumstances; and

- at any given time, the employee should be expected to take orders from only one supervisor" (p. 120).

Span of Control

The number of subordinates a supervisor can effectively supervise is called the span of control. While some scholars suggest a specific ratio of supervisors to supervisees, others suggest span of control varies depending on where one is in the hierarchy. For example, the chief of police has the narrowest span of control, which widens as one moves down the hierarchy. Of course, additional supervisors comes with a price tag - something that also must be considered.

Reference

Cordner, G. W. (2016). Police Administration (9th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Lesson Activities

Plagiarism Test

Prior to beginning of the writing assignments, it is mandatory that you take and successfully pass the Indiana University Bloomington School of Education Plagiarism Test.

The purpose of this assignment is to inform students who may be unsure of what constitutes plagiarism. Plagiarism will be dealt with harshly in this course and it is important that you understand what it is and how to avoid it. This is an excellent site that explains what plagiarism is and provides examples. Note: No writing assignments will be scored until the Plagiarism Test has been completed and certification placed in the Drop Box.

You MUST pass this test by the end of Lesson 2. When you pass the test you will receive a certificate indicating that you have passed the test. You may take this test as many times as necessary but you must pass the test.

Please copy that certificate and place it in the dropbox applied for this assignment.

APA Tutorial

Wendy K. Mages's APA Exposed is an online tutorial which takes you from beginning to end of APA, and explains it both in visual and audio formats. This tutorial must be completed before any of your writing assignments will be scored. The purpose of this assignment is to inform students on proper use of APA style. It is strongly suggested that students pay close attention to this tutorial as a portion of the score for all writing assignments will turn on proper use of APA Style.

When you complete Module 4 of the tutorial, take a screen shot of this page. and submit it to the "APA Drop Box" Drop Box as an attachment. This will be used as proof that you completed the tutorial. This assignment is due at the end of Lesson 2. Late submissions will not receive credit for this assignment. However, this assignment must be completed before any writing assignment will be scored.

NOTE: Students who have previously taken this test need only submit the appropriate form. It is not required that the student retake for credit.

The purpose of this assignment is to inform students on proper use of APA style. Note: No writing assignments will be scored until the APA Tutorial has been completed and the poll submission is placed in the Drop Box in the Lesson 2 Activities folder.