The Historical Perspective and Police Culture (Printer Friendly Format)

page 1 of 13

Introduction

This lesson tracks the history of police administration and management from its early conception to the present day. The chief architects of police administration and management derive from both practitioners and academics, and presented here are the leading schools of thought, including public administration, business management, and police management. At present, police management tends to be a blend of the historical schools of management. Students should be familiar with the various schools as well as their historical roots and major ideas.

After completing this lesson, you should be able to:

- outline the major schools of management;

- review Peel’s Nine Principles;

- identify the leading contributors to police management thought;

- analyze the concept and characteristics of the police subculture;

- outline the role of women, minorities, and gay officers in policing.

page 2 of 13

Road Map

To Read

Below are the lesson readings. Complete these before progressing to the author's commentary.

- Chapters 1 & 2 of Proactive police mangement;

- Chapters 1 & 2 of Handbook of Police Administration.

To Do

Complete the following lesson assignment:

- Discussion Forum Activities

- Plagiarism Test

- Start Writing Assignment #2 -- Topic Paper

- Submit your Exam #1 Request Form

page 3 of 13

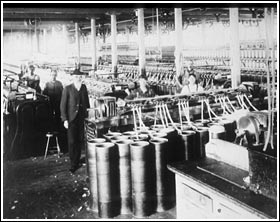

The Industrial Revolution and Traditional Management: 1750-1900

Present day policing has as its foundation the ideas of Henry Fielding and Sir Robert Peel of early nineteenth century London. The Industrial Revolution had an enormous impact on rural life in England because it offered the promise of a steady income and stability. From the farms a great influx of people moved to the major urban centers in search of a better life. But instead of fulfilling their dreams, they became part of a nightmare of poverty, unemployment, and crime. This caught the attention of Sir Robert Pell, who was mainly responsible for the legislation passed in Parliament entitled The Metropolitan Police Act. The main duty of this policing organization would be crime prevention and protection of property—not law enforcement.

page 4 of 13

The Nine Principles of Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel was instrumental in having the Act for Improving the Police in and Near the Metropolis (the Metropolitan Police Act) passed in the English Parliament in 1829. Peel had a specific vision as to the principles under which the police should operate. The nine principles that he penned nearly 200 years ago are just as important to proper police operations today as they were in early nineteenth-century London.

- The basic mission for which the police exist is to prevent crime and disorder.

- The ability of the police to perform their duties depends on public approval of police actions.

- Police must secure the willing cooperation of the public in voluntary observance of the law to be able to secure and maintain the respect of the public.

- The degree of cooperation of the public that can be secured diminishes proportionately to the necessity to use physical force.

- Police seek and preserve public favor not by catering to public opinion but by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to the law.

- Police use of physical force to the extent necessary to secure observance of the law or to restore order only when the exercise of persuasion, advise and warning is found to be insufficient.

- Police, at all times, should maintain a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and the public are the police, the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

- Police should always direct their attention strictly towards their functions and never appear to usurp the powers of the judiciary.

- The test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with it.

Sir Robert Peel

Police misbehavior can usually be found to violate one or more of Peel’s nine principles. Perhaps more importantly, we have allowed our police to stray far beyond the basic mission of prevention of crime and disorder first laid out by Peel. Indeed, in most instances, police no longer look like police officers because they have taken on a more militaristic look. For example, the dress shirts, tie, dress slacks, and shined dress shoes have given way to a different look. Many of today’s police dress in dark blue or black wash and wear pants and shirt, wtih some police departments choosing a one-piece jumpsuit. Shined dress shoes have been replaced by either dark tennis shoes or laced up paratrooper jump boots and bloused pants. It is now common to see police officers attired in assault gear complete with helmet with automatic assault weapons, with trigger finger at the ready.

Along with revised uniforms has come a revision of the vision of policing. Police officers no longer see themselves as members of a "helping profession," as conceived by Sir Robert Peel, but instead view themselves as “law enforcers." Whereas law enforcement had always played a minor role in policing, the shift in paradigm toward "enforcement" can be seen in the many martial metaphors in current use: “War on Crime,” “War on Drugs,” and now “War on Terror.” This is not their fault but rather ours. We have placed upon our police ever increasing demands, making them responsible for social problems, which are beyond their control. The latest increase in responsibility has come by classifying police as the first line of defense against acts of terrorism. Little wonder they have become increasing militaristic in both uniform and thought. Reversing police militarism will not be easy because it has become so well entrenched and is reinforced by the constant drumbeat of “War on Crime, “War on Drugs,” and “War on Terror.” Unless serious effort begins to reclaim policing, Peel’s Nine Principles will never become a reality.

Reference

Dempsey, J. and Forst, L. (2008). An introduction to policing. Belmont, CA: Thompson-Wadsworth, 7-8.

page 5 of 13

Scientific Management

Scientific management, otherwise known as the machine model, places major emphasis on efficiency, orderliness and output. Often referred to as the Father of Scientific Management, Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915) was born the son of well-to-do Quaker parents in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After dropping out of Harvard University because of poor vision, he began working as a patternmaker, gaining experience as a laborer. He eventually earned a mechanical engineering degree through correspondence courses with the Stevens Institute of Technology. He went on to become a professor at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College.

Frederick Winslow Taylor

He believed that industrial management of time was very inefficient. He posited that management should be expressed as an academic discipline, and that optimum outcome could only be achieved by means of a partnership between well-trained and educated managers and a supportive and inventive workforce. He believed that management and labor needed each other, and that they could work in harmony devoid of trade unions.

Taylor established four basic principles for this approach to scientific management: division of labor, unity of command, one-way authority, and narrow span of control. This bureaucratic model dovetailed nicely with the existing paramilitary police organizations.

O.W. Wilson and William H. Parker are two of the early leaders in police administration. Both Wilson and Parker rose through the ranks to become chiefs of their respective departments. Both Wilson and Parker were also heavily influence by their time and experiences in the U.S. military during World War II. Wilson authored what has often been hailed as the seminal work entitled, Police Administration (1950). Although no longer in use, it was extremely influential during its time.

As leader of the Los Angeles Police Department from 1950-1968, Parker was a leader in police innovation and led the way demanding education, psychiatric exams, and probationary periods for new officers. He is also responsible for creating a file examining the methods used by criminals (modus operandi), research and planning divisions, and other procedures that led the way for departments across the United States.

page 6 of 13

Human Relations and Participative Management

The human relations approach to management takes one giant step away from scientific management in that the top police executive moves away from the top-down boss to a team leader role. Under this rubric, the top police administrator becomes more of a personnel facilitator/motivator. She or he finds ways to provide opportunities for personnel to realize self-actualization and to develop their full potential. Of singular importance to line personnel are promotion and matters of job security. Line and mid-level personnel get a stake in the decision-making process when allowed input as to how the organization addresses such sensitive issues as crime prevention and citizen support through community policing. Thus, the management process becomes a shared process between the top police administrator and his or her employees.

page 7 of 13

Behavioral and Systems Management

Both behavior and system management complement the human relations approach to management. Their major impact can be found in the areas of fiscal management, budgeting, and the planning process. There are three major goals in behavioral management.

- a goal stated empirically;

- success not measured at 100%;

- a manner in which to measure success.

In coming lessons, the behavior-systems approach to management will be discussed and how it developed from the systems for accountability, planning, and fiscal management (listed below).

- Management by objectives (MBO);

- Program evaluation and review techniques (PERT);

- Programming, planning, and budgeting (PPB);

- Organizational development (OD);

- Zero-based budgeting.

page 8 of 13

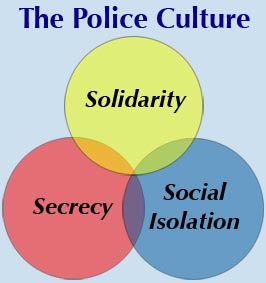

The Police Culture

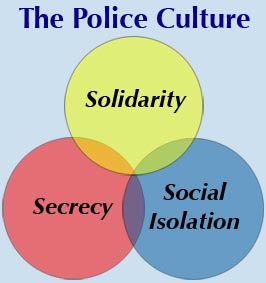

Culture, existing in most levels of society, may be defined as "the set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution or organization." This would seem to speak to the characteristics of a society in general. However, police have often been said to be a subculture—a part of but separate from the whole. Subculture has been defined as "an ethnic, regional, economic, or social group exhibiting characteristic patterns of behavior sufficient to distinguish it from others within an embracing culture or society." This definition seems appropriate when attempting to characterize a police organization. The police subculture has been characterized by three major norms: secrecy, solidarity, and social isolation.

Secrecy – Police officers involved in many sensitive operations and investigations often require secrecy. However, the issue of secrecy in policing far exceeds that which is necessary for normal operations. Secrecy in policing often extends to keeping silent about police deviant and even criminal behavior. Clearly, in society an informer or a rat is looked down upon. In policing, it is taken much more seriously. For example, if a police officer were to inform on another officer involved in criminal behavior, the informing officer would be viewed as a stool pigeon even though she or he did what his or her oath of office required.

Solidarity – Most police officers believe that the only person to come to his or her aid will be another police officer. Each officer is acutely aware of his or her human side and the potential for complaints from the public or some violation of departmental rules and regulations. Under such circumstances, fellow officers are expected to come to the aid of the officer(s) in trouble. The "us v. them" mentality not only refers to the adversarial perception of police v. public, in which most police sincerely believe, but also extends to within the police organization itself—in that line officers do not trust police administrators. This distrust was the driving force for the modern era of police unionization, which began in 1969 with the Patrolman’s Association of New Orleans (PANO).

Social Isolation – Because of the nature of their work, police officers feel isolated from the public, an isolation partly self-imposed. Many police officers see what they do as "asshole control," with a perception that they are pitted against the public in a "them vs. us" contest. They also believe that the general public dislikes them, though research indicates that the public overwhelmingly feels positively toward the police.

Reference

page 9 of 13

The Police Subculture

Police Argot and Communications

Subcultures are known to spawn their own particular argot (slang) specific to the everyday workings of the members of the organization. Likewise, small groups of officers within a precinct or squad may create their own argot so as to hide from other officers or supervisors where they are or what they're doing. Although this may seem innocuous to some, this type of covert evasion of supervision can be most problematic for supervisors and administrators. Such was the case involving "The Buddy Boys." In this case, 13 New York City police officers in one of the NYPD Brooklyn precincts were indicted for stealing and selling drugs. In testimony given before the Mollen Commission, one officer told how he communicated with other corrupt officers using preset argot when contacting other Buddy Boys over the police radio to set up robberies of drug dealers. Now, thanks to cell phone technology, police officers have a more covert communication capability than ever before. Transmissions over the police radio system are taped. Cell phone communications are not.

Police also use argot to enhance their position in the eyes of the public, as implied in the the time-tested phrase, the thin blue line. Police commonly see themselves as all that stands between citizens and total anarchy. In some sense, this is true when one considers what happens when massive power failures occur such as the 2003 blackout in the Northeast that affected almost the entire state of New York. Without electricity, most communications are cut creating a disconnect between citizens' calls for services as well as intra-police communications. Similarly, in times of great natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina, all communications are lost and looting and anarchy does reign supreme. However, these are the exceptions to the rule. For the most part, millions of people go through their daily routines in comparative safety.

Reference

page 10 of 13

The Police Subculture - Police Cynicism

Citizens who have had the misfortune to run afoul of traffic codes often comment negatively about the attitude of the officer they encountered. Most citizens come away from their encounter with the perception that the officer was cold, dispassionate, and mean—particularly when a citation was issued. Most police officers develop what has been called the working personality, a mental barrier erected to shield them from emotional connection with people as well as the horrendous crime scenes and tragedies that are often a part of daily life in policing. So what may seem to the casual observer as cold and dispassionate may well be just the way that particular officer has developed to cope with the job.

True police cynicism is easy to develop because of the nature of police work. Most citizens call the police to report some type of negative incident. Often these incidents involve persons of a less than savory nature. Moreover, police officers assigned to areas that include housing projects and/or lower socio-economic neighborhoods have daily contact with poverty, addiction, and all of the other societal maladies that accompany daily life in these neighborhoods. It is not difficult to understand how officers constantly exposed to this scene can become jaded and cynical.

Reference

Balch, R. (1972). The Police Personality: Fact or Fiction? The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, 63(1), 106-119

page 11 of 13

The Police Subculture - Internal Sanctions, Solidarity, and Social Isolation

Because policing has long been a close-knit occupation, internal sanctions by peer groups have been the norm. Police officers graduating from the academy are expected to conform to the group norms of the department and even a particular district or precinct. These expectations are not written but passed on from the older officers to the younger officers by means of their actions or verbal instruction. Older officers may even test younger officers to see if they will conform to group norms by placing the younger officer in a situation and noting his/her manner of dealing with it. These are usually simple situations such as gratuity acceptance or some other minor infraction of department rules and regulations. The purpose is to see if the officer will go along with the group. If he or she does go along, the young officer is tested in greater forms of misbehavior. Failure to conform can bring much grief on the miscreant officer. Perhaps the greatest of all transgressions of group norms in policing is informing on another officer. This is true even in cases of serious criminal behavior. Most officers will do all they can to avoid being branded as an informer or stool pigeon because life in police, once that label is affixed, is all but intolerable.

Sanctions and adherence to peer group norms also engenders solidarity. Solidarity is also taught to young officers as a way of bringing them into the fold. Young officers are taught that the public is the enemy or more commonly, "assholes." Older officers will commonly say to those younger, "There are two kinds of people in this world: the police and the assholes." Such rhetoric is somewhat shocking to young officers, at first. However, after months of dealing with the social problems of society, many buy into the concept.

Most police officers do not work the traditional 8 to 5 schedule as most departments are of the few we-never-close organizations in city government. Two-thirds of the hours police officers are required to work puts them at odds with the average work-a-day world. They must work evenings and at night, not to mention weekends and holidays. Often young police officers gradually loose their circle of civilian friends, if for no other reason but their inability to socially connect. As such, this leaves only other police officers and police families as the available social connections. This can have negative consequences because police officers reinforce the police worldview, which is often skewed and cynical.

Reference

page 12 of 13

The Police Subculture - Minority Group Structures in Policing

Traditionally, the policing occupation has been mainly the province of white males. Not until the late 1960s and early 1970s did minorities began to enter policing in substantial numbers. The experience of black officers was first chronicled in the groundbreaking book, Black in Blue (1969), which spoke of how black police officers were accepted under the work situation but excluded from the off-duty social scene of white police officers. Also, barriers had been erected to keep blacks out of the detective and upper ranks of policing.

This was true for all minorities but in particular female minorities. Minority males had a much greater level of acceptance by white officers. Minority females, on the other hand, were not only looked down upon by white males but also male police officers of their own minority group. It was believed that female officers could not meet what many viewed as the demanding physicality of policing. Females proved them wrong. Research conducted on the performance of females as police officers has been positive across the board. Females were found to have had the same performance rates of their male counterparts and established better rapport with citizens. Finally, they also generated much less in the area of citizen complaints, which did not go unnoticed by police supervisors and administrators.

The late 1960s and early 1970s also witnessed the open entry of members of the gay and lesbian community into policing. Just as females were viewed as unsuitable to manage the demands of policing, so were gay and lesbian officers. Beyond sexism, many police officers of all stripes were challenged by their own homophobia, and gay and lesbian officers had their own special rite of passage into policing to experience. However, time did for them the same as for female police officers. Gay and lesbian officers demonstrated to the straight officers that they could do the job. This won over, in some circles, grudging acceptance to their presence in policing.

page 13 of 13

Lesson Activities

There are two discussion questions for this lesson. After you have posted your answers to the questions, don't forget to read and respond to the rest of the class postings. Also you may need to start Writing Assignment #2 -- Topic Paper.

In Chapter 1, the author holds that "attitude" plays a major role in police leadership? Do you agree with that belief? If so, why and if not why not?

In Chapter 1, the author holds that "attitude" plays a major role in police leadership? Do you agree with that belief? If so, why and if not why not?

Post that principle in your response to the Attitude in Plice Leadership Discussion Forum. Defend your answer.

In Chapter 2, the author surveyed police chiefs regarding incorporating community policing characteristics in midsize and large police departments. Having read this chapter, do you agree with his findings? Is so, why and if not why not?

In Chapter 2, the author surveyed police chiefs regarding incorporating community policing characteristics in midsize and large police departments. Having read this chapter, do you agree with his findings? Is so, why and if not why not?

Post your response to the Incorporating Community Policing Characteristics Discussion Forum. Defend your answer.

Writing Assignment #2 -- Topic Paper

Writing Assignment #2 -- Topic Paper

Each student will be assigned a topic regarding police organization and management during week 2. Students will be required to research their topic in the scientific journals, and shall incorporate no less than five (5) scientific journal articles of their assigned topic in their paper. The paper shall contain no less than 3,500 words, which s/he will be the sole author.

The paper requires that you present the facts about which you have read. These facts, however, must come from what you have read in those articles and only those articles. No other sources, including the textbook, are allowed. Aside from the Introduction and Conclusion, I expect each paragraph to have at least one citation in it directing the reader to the source of the information contained. It is expected that students will construct their papers in such a way as to have all five articles represented equally. The Introduction and Conclusion shall consist of no more than one page each.

All journal articles used to construct this paper

- cannot be more than 10 years old, and

- must be cited in the text of the paper and properly referenced. There are no exceptions to this rule!

The paper will be submitted in the Drop Box named Topic Paper. Papers are due during the week 10. Late papers will be accepted during the week 11. Papers submitted after that time will not be accepted. All late papers are subject to a 10-point reduction in grade.

Plagiarism Test

Prior to beginning any of the writing assignments, it is mandatory that you proceed to this Web site take and successfully pass the Indiana University Bloomington School of Education Plagiarism Test. You MUST pass this test BEFORE the end of Week 3. When you pass the test you will receive a certificate indicating that you have passed the test. Please copy that certificate and submit it in the drop box named Plagiarism Test. You may take this test as many times as necessary but you must pass the test.

Exam Reminder

Exam Reminder

It is now time to submit the Exam Request Form for the first exam. Click on Exam #1 Request Form to access the link. Be sure to do this immediately and read the exam instructions on the form. Your exams will not be mailed to your proctors until you submit your Exam Request Forms.