Poetic Nation: Emerging Voices in American Literature -- Part II (Printer Friendly Format)

page 1 of 10

Lesson Two

Poetic Nation: Emerging Voices in American Literature – Part II

Lesson Two continues our examination of poetry at the end of the nineteenth century with a close examination of the poetry of Emily Dickinson.

Objectives

By the end of this lesson you should

- Better understand the importance of Emily Dickinson’s poetry in the emergence and growth of a unique American literature

- Be able to explicate or “unpack” her poems

- Have a general sense of the structure of her poems (meter, rhyme, grammar, and so on)

- Be familiar with several of her best known poems

- Be able to trace several of her most common themes in her work

Reading

Read online lesson commentary. See Course Schedule in the syllabus for assigned readings.

page 2 of 10

Commentary

Emily Dickinson is one of the most significant poets writing at the end of the nineteenth century. Unlike Whitman, who was outgoing and frequently occupied with promoting himself and his work, Dickinson lived the life of a recluse. She ventured away from home only a few times, spending one year at a seminary and taking a few brief trips to Washington, Philadelphia, and Boston. The household she grew up in was devoutly Christian. She dressed only in white and her primary social group consisted of family members and a few others with whom she corresponded. She avoided social gatherings and often refused to see people. What is most surprising for a poet of her current stature and influence is that she only published a dozen poems during her lifetime and those were published anonymously.

Despite her reclusive nature—or perhaps because of it—Dickinson was a prolific poet, producing nearly two thousand poems. As you read in her biography, most of her work comes from forty notebooks found after her death.

Dickinson’s poetry is lyrical. “Lyric poetry” refers to short poems in first person that express intense and highly personal emotions.

We noted in Lesson One that much of Whitman’s stature ultimately rests on the innovation of the form and content of his poetry and our ability to differentiate it from European models. Much of Dickinson’s allure also relies on the fact that her poetry is unique. Her poems bear no clear influence from the long history of poetry that precedes them (she never even read Whitman, having been told by her father that the material was inappropriate).

To a romanticist, she is the epitome of a great poet—driven by a compulsion to create in the absence of stultifying external influences. Her poetry embodies a personal and passionate struggle with pain, loss, love, and death and her uncertainty about the existence of God and the meaning of life.

Not all of her poems are as dark as this brief introduction implies. Dickinson is at times playful and humorous, but her most memorable poems tend to be those that confront complicated human emotions and ideas.

page 3 of 10

Dickinson’s Style and Tips on Reading Her Poetry

In many ways, Dickinson’s style prefigures modern poetry during the first part of the twentieth century. She employs grammar, punctuation, rhyme, and meter in unconventional ways, a tendency that did not become popular until decades after her death.

Personas

It is important when reading Dickinson’s poetry to remember that the speaker of every poem is not necessarily Dickinson. Typical of lyric poetry, Dickinson’s poems often employ “personas”; that is, she invents a fictional character (an implied poet, alter-ego) and then speaks through it. Thus, the speaker in Dickinson’s poems is not necessarily Dickinson herself, but a mask that she dons for the occasion. It may be easiest to understand persona by thinking of an actor playing a role in a film. We know that the actor is not the character—Mark Hamill is not Luke Skywalker, Julia Roberts is not Erin Brokovich. As Dickinson explains in a letter she wrote to Thomas Wentworth Higgins, the editor of The Atlantic Monthly, "When I state myself, as the representative of the verse, it does not mean me, but a supposed person."

An example of persona can be found in “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” (#340/280) from your assigned readings. In this poem, the speaker is suicidal and imaging her funeral and internment, but we cannot assume that this reflects suicidal notions in Dickinson. You might also note, when reading this poem, that by avoiding the tendency to see the speaker as the poet (by acknowledging her use of persona), we open the poem up to a broader reading. Consider the final stanza:

An then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down—

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing—then—

If we dismiss persona, we might be tempted to read this stanza as only narrating her burial (“to hit the World” = to fall into the Earth; to be “Finished knowing” = to lose, at death, the ability to think). But if we acknowledge the presence of a persona—a mask—then we open up the possibility that the poet behind the persona may be articulating a more significant point: a differentiation between the physical world and the world of the mind, between the real and the imaginary. It is reason that holds us aloft, and when reason fails (“a Plank in Reason, broke”), we fall to the physical world, a world where we cannot “know” any more. Just as physical desire is sometimes said to deprive us of our ability to think, Dickinson may, through the poet’s persona, be telling us that the only way we can rise above the physical world is through reason.

page 4 of 10

Language

Perhaps the most striking characteristic of Dickinson’s work is her use of language. Enamored with words, she is particular about her individual word choices, and to best appreciate her work, we need to be equally careful when reading her poems.

For example, in “There’s a certain Slant of light” (#320/258) from your assigned reading, note the use of “Heft” in the first stanza:

There’s a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons—

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes—

It is too easy to read “Heft” as simply a synonym for “weight” (as in “a certain slant of light . . . that oppresses like the weight of Cathedral Tunes”). The word “Heft” is a richer word choice. It does imply “weight,” but it has other meanings as well. The OED (Oxford English Dictionary) provides a number of other connotations for “Heft”:

—Weight, heaviness, ponderousness.

—The bulk, mass, or main part

—To lift, lift up

—To lift for the purpose of trying the weight

—To confine nature, to restrain

Dickinson, who was fond of reading the dictionary, would have been familiar with the multiple meanings of words such as “heft.” When we consider the other possible meanings for “heft,” we expose an ambiguity about “Cathedral Tunes” that we might have otherwise missed in assuming Dickinson meant only “weight.” (NOTE: In Christianity, hymns are nearly always directed toward God or another heavenly figure, such as the Virgin Mary or the Catholic saints.)

In selecting the word “heft,” Dickinson summons the qualities of religious music that elevate the individual, raising someone above the physical world into the spiritual—the very purpose of religious music. Included in this lifting up is the sense that hymns lift a person into a realm that is massive and unwieldy (ponderous), implying that the world of the divine is so massive it is difficult to handle. But in the word “heft” also connotes negative aspects of religious uplifting. The divine confines and restrains nature with its weight and mass. Furthermore, the passage may also be read as referring to the quest for truth in religion. One might “try the weight” of the divine of which hymns sing in order to test his or her ability to handle that divine.

We could consider this single word for a long time, unpacking its relevance to the poem as a whole. This richness of Dickinson’s word choice and reflects the importance of every word in her poems. In choosing “heft” over a less resonant word, such as “weight,’ Dickinson manages to connote both the positive and negative characteristics of religious experience, illustrating that the religious is both uplifting and burdensome.

page 5 of 10

Meter

Dickinson’s poetry often follows the meter found in English hymnals. This contributes to the ease with which many of her poems can be sung. One interesting bit of trivia related to the rhythm of Dickinson’s poems is that many of them seamlessly match the theme song to the Gilligan’s Island television show.

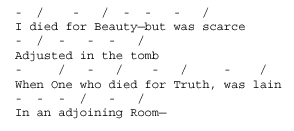

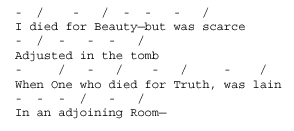

When reading Dickinson, pay attention to the arrangement of weak and strong syllables in her poems. For example, note the pattern in the first stanza of “I died for Beauty—but was scarce” (#448/449):

Note the reoccurrence of three weak syllables in lines 1, 2 & 3 and the presence of four iambic feet in line three. Why does the rhythm in line three stand out?

Try accenting the strong syllables while you read the passage aloud.

For more information, see this Wikipedia article about hymn meter.

page 6 of 10

Rhyme

Many readers overlook the fact that Dickinson uses rhyme in her works, because the types of rhyme she uses are varied and often unfamiliar to the casual reader. For example, in addition to the “true rhyme” with which we are all familiar (true/blue), we also find “identical rhyme” (port / deport or write / right), “near rhyme” (soul / oil), “eye rhyme” (through / though) and others. [NOTE: Types of rhyme are known by many names. For example, “near rhyme” is also called “imperfect rhyme,” “oblique rhyme,” “off rhyme,” “half rhyme,” “slant rhyme,” and “approximate rhyme.”]

For the purposes of this course, it is probably enough that you realize all rhyme is not the type we find in nursery rhymes and Hallmark cards and that Dickinson’s poetry contains a rich and varied use of rhyme.

For more information, see the following article about rhyme.

page 7 of 10

Major Subjects and Themes

Death. Death is prevalent throughout Dickinson’s poetry. It is sometimes thematic, as in “I died for Beauty—but was scarce” (#448/449). Other times death becomes a persona, as it does in “Because I could not stop for Death—” (#479/712), but always the role death plays in Dickinson’s work is as a defining force in life. For Dickinson, death was the doorway to “immortality,” and through death we come to understand life, God, and the soul.

It is important to note that Dickinson does not simplify death or reduce it to a cliché. She remains aware of the complexity of death as a concept and as an event, as she remains aware of the complexity of many other issues (e.g. God, love, life).

Religion. As you learned from her biography, Dickinson was raised in a very religious household. Her struggle with religion—particularly her struggle to understand the concept of God—is apparent in many of her poems.

Pain and Dread. Dickinson has been called the poet of dread. In her poetry, so many references to pain and dread abound that it is easy to conclude that she was bitterly unhappy; however this is an oversimplification. Dickinson was a bright, perceptive poet. She realized that pain is part of life and much of the pain we find echoed in her poetry can be better explained as an attempt to grasp the complexity of life, to achieve some understanding of the role pain and suffering played in the framework of the world.

page 8 of 10

Final Word

Above all Emily Dickinson is a passionate and very personal poet whose poems reward careful reading. The poet, as she says in “This was a Poet—It is That” (#448, not assigned reading), “distills amazing sense from ordinary meanings,” and we find evidence of this distillation throughout her work.

The acclaimed writer, Joyce Carol Oates, says of Dickinson:

“No one who has read even a few of Dickinson's extraordinary poems can fail to sense the heroic nature of this poet's quest. It is riddlesome, obsessive, haunting, very often frustrating (to the poet no less than to the reader), but above all heroic; a romance of epic proportions. For the "poetic enterprise" is nothing less than the attempt to realize the soul. And the attempt to realize the soul (in its muteness, its perfection) is nothing less than the attempt to create a poetry of transcendence—the kind that outlives its human habitation and its name.”

(see “Additional Resources," next page, for a link to the full article)

page 9 of 10

page 10 of 10

Assignments

1. Take Reading Quiz 2, located in the Lesson 02 folder on the web site.

No journal entries or essay questions for this lesson.