Main Content

Lesson 3 The Economics of Higher Education Institutions

Why are colleges facing financial difficulties?: The expenditure-based portion of the story

The revenue challenges just noted are compounded by a number of processes that cause costs within higher education to rise faster than costs in other industries. As a result, the normal processes within colleges and universities require substantial yearly increases in revenue. If revenues do not increase or even fall, then the functioning of colleges and universities can be severely disrupted in ways that promote tension and frustration. The institutional leaders who will thrive in the future will be those who can lead thoughtful discussions about cost control and implement the cost-conscious policies that emerge from those discussions. Those individuals at lower levels who can identify, initiate, and sustain approaches that reduce costs while not harming quality will also become increasingly valuable. To develop those skills, one needs to first understand why costs tend to rise faster within higher education institutions than in other organizations, and we present here several of the most common explanations for this pattern.

Explanation #1: The Revenue Theory of Costs

The revenue theory of costs essentially states that colleges and universities are like cookie monsters. Watch the following two videos, keeping the following question in mind: How many cookies will a Cookie Monster eat?

Question Time

Now that you have seen the videos, let's return to the question: How many cookies will a Cookie Monster eat?

How does the cookie consumption of a Cookie monster relate to revenue theory, you ask? The revenue theory of costs is essentially answering the same question but replacing the Cookie Monster with a higher education institution. In other words, how much will a higher education institution spend? Knowing that colleges and universities are like a cookie monster, how would you answer that question?

Revenue Theory, examined

Of course, Howard Bowen, who proposed the Revenue Theory (RT) of costs in his 1980 book, The Costs of Higher Education, was not thinking about cookie monsters when developing this theory. [Ron Ehrenberg, in his book Tuition Rising, proposed the idea of universities as cookie monsters when making a similar point as Bowen.] Bowen had a much more abstract description of his theory:

[A]t any given time, the unit cost of education is determined by the amount of revenues currently available for education relative to enrollment. The statement is more than a tautology, as it expresses the fundamental fact that unit cost [i.e., the cost of education] is determined by hard dollars of revenue and only indirectly and distantly by considerations of need, technology, efficiency, and market wages and prices. (p. 19)

The basic logic underlying his theory were presented as the five laws of higher education costs:

- The dominant goals of institutions are educational excellence, prestige, and influence.

- In quest of these goals, there is virtually no limit to the amount of money an institution could spend for seemingly fruitful educational ends.

- Each institution raises all the money it can.

- Each institution spends all it raises.

- The cumulative effect of the preceding four laws is towards ever increasing expenditure.

So, just like the Cookie Monster, universities can never be satiated. Bowen’s theory does not, however, imply that the individuals who are working within higher education are greedy as the forces driving the theory can be benevolent attempts to advance excellence and prestige. Student affairs officers advocate for greater spending on campus programming and counseling services, enrollment management officers call for activities that promote retention, faculty request resources that will allow them to produce research that advances society and the institution’s reputation, and other folks throughout the campuses have their own resource requests that could improve important outcomes. The challenge for institutional leaders with limited budgets is to deny many of these requests while keeping people motivated to reach organizational goals. The challenge for others is to recognize the cost implications associated with their attempts to enhance quality and seek to find an appropriate balance between quality and cost.

Explanation #2: The Cost Disease

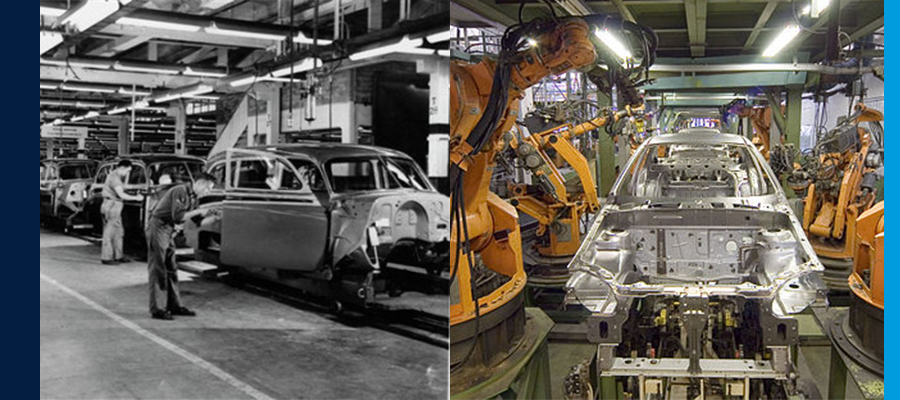

To understand what the cost disease looks like, let’s compare an industry with the cost disease (higher education) with an industry without the cost disease (automobiles). Below you see two photos that show the production of automobiles at various points in industry, with the first picture describing production half a century ago and the second picture describing production recently.

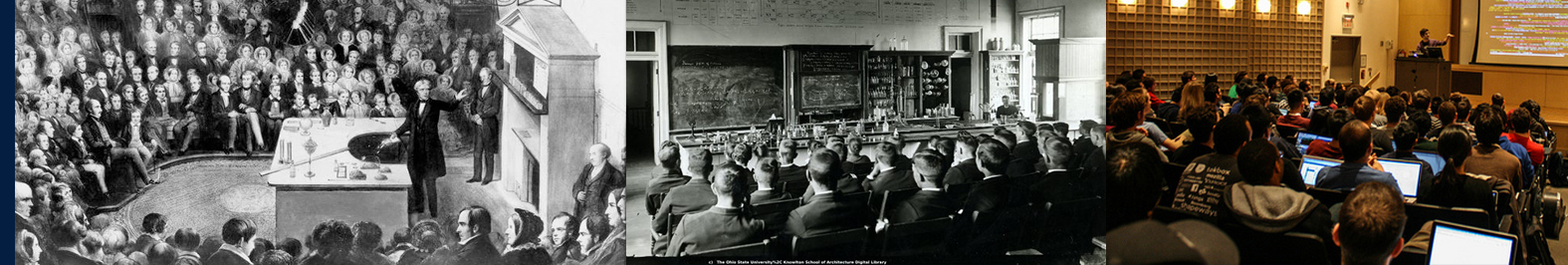

The next set of pictures describes the production of residential instruction within higher education at various points in history. The first picture shows a lecture from 150 years ago, the second shows a similar education scene from 50 years ago, and the third shows higher education today. [We chose pictures of a class with a large number of students, but you can imagine similar scenes for smaller classes by simply shrinking the room and the number of students. There are slight differences in class size across these pictures, but for the purposes of the upcoming questions, you should ignore these differences. Assume that each class has an identical number of students.]

Let us now ask you a number of questions regarding each of these two contexts that will highlight important considerations pertaining to the cost disease.

Questions 1 and 2:

How did the number of workers involved in production of an automobile change over time? How did the number of workers involved in the production of instruction (for a single course) change over time?

Question 3:

How did the use of technology change over time in both of these cases?

Question 4:

How do the required skills of workers change in each of these cases?

Logic of Cost Disease

Let us now combine the answers to each of these questions to explain the basic idea and logic of the cost disease. Industries with the cost disease, like higher education, do not increase productivity growth over time, which means they do not increase the amount produced per worker over time. Consequently, the cost of educating students will not decrease over time and could actually increase if the compensation provided to workers increases over time.

Other industries, like the automotive industry, are seeing large productivity growth, as the amount produced per worker increases rapidly after a robotics-based production line is implemented. The cost of producing each car then falls rapidly. Because the individuals designing and overseeing the robotics are vital to this process, individuals with advanced education and skills, which are needed to design and oversee robotics, become in high demand and subsequently experience salary growth. These salary increases in other industries have implications for higher education, because colleges and universities must compete with other organizations for highly-educated individuals. That competition causes faculty salaries to grow, which leads to rising costs because the amount produced per faculty member is not growing. Those rising costs are the outcome of the cost disease.

To this point, we have primarily thought about the cost disease from the perspective of residential instruction. Other areas of higher education are less affected by the cost disease. For example, course registration used to take place within a large gymnasium filled with employees who met individually with students and helped them register for classes. Today, students register for courses using programs on the internet where humans do not individually assist students and instead simply design and manage registration software. In many ways, registering students is like building automobiles in that humans could be replaced with technology. If higher education institutions are going to reduce costs, then methods must be developed that allow individual workers to produce more than they have in the past.

Other Explanations

Scholars and practitioners have proposed other explanations for rising costs beyond the Revenue Theory of Costs and the Cost Disease. For example, some authors propose that a principal-agent problem exists within higher education, where the agents (faculty, administrators, board members) are not properly focused on the goals of the principals (students, parents, alumni, donors, taxpayers) for whom the organizations are designed to serve. Instead, employees and leaders of the organizations focus on their own goals and interests, which lead to instruction, activities, and research on topics that are of personal interest to employees of the institution but not of great interest to the students and other key principals. These activities often draw narrow audiences and consequently increase the institution’s costs. To address this issue, an institution must develop a culture focused on students, alumni, and other key principals and employ individuals who can identify and regulate the natural human tendency to focus partially on one’s own interests.

Costs can also increase when students, donors, and others desire high-end facilities (e.g., dormitories, recreation centers), winning athletic programs, high rankings, or other items, and universities try to attract those students to their campus by meeting their desires at higher levels than competing institutions. When multiple institutions compete in this way, an arms race can ensue that increases costs at all schools but does not improve the relative position of any institution. Individual institutions will have a difficult time stopping an arms race, as their relative standing will fall if they choose to not participate in the race while others do. Collective agreements across institutions to restrain costs are the best way to address arms races, but such collective agreements are difficult to reach.

By this point, I hope you have healthy appreciation for the many forces that lead costs to rise more rapidly in higher education than in other industries. Colleges and universities are complex organizations, which allows each of these explanations to contain some validity and means that narrow attempts at cost control will likely be unsuccessful. Efforts to restrain costs must be done with care, because the forces propelling costs are also the forces that have promoted the considerable quality that exists within the higher education system. Faculty autonomy, competition across institutions, and the human element of providing education serve valuable purposes. Finding the right balance between cost control and other goals is a difficult task, that will only grow more difficult over time as financial challenges increase.

![]()