HIED545:

03_Lesson

Overview

Most colleges and universities are non-profit organizations whose primary goals include developing students, creating knowledge, enhancing their reputation, and serving society. They are not seeking to make a profit but are instead simply seeking to generate enough money to cover the costs of the activities they wish to conduct. That simple goal of supporting themselves, however, is proving to be quite a challenge. As this lesson will explain, the financial challenges facing colleges and universities are growing, which has important implications for these organizations, the people they employ, and the students they serve. For those planning to work in higher education, those implications can be daunting when viewed from certain angles but they can also be viewed as opportunities from other perspectives as they increase the value of individuals who can do more with less and have a willingness and talent for engaging in entrepreneurial activities that advance mission while improving finances.

This lesson will enhance your understanding of where colleges get their money, how they spend their money, and the reasons why colleges are increasingly facing financial challenges. As you will see, the answers vary dramatically across institutions. Some institutions primarily pay their bills using tuition dollars from students, others rely primarily upon governmental appropriations, and others rely equally upon a number of different revenue sources. The assignment for this lesson will require you to learn more about the finances of your institution. As this lesson emphasizes, an understanding of finances is important because financial considerations permeate almost every decision.

Essential Questions

As you explore the lesson commentary and assigned reading materials, consider the essential question(s) below. They will help guide your learning and ensure that you have mastered the key concepts of this lesson.

- Where do higher education institutions get their money?

- How do higher education institutions spend their money?

- Why is the challenge of balancing budgets becoming increasingly difficult for higher education institutions?

Objectives

Upon conclusion of this lesson, learners will be able to:

- match revenue profiles to institutional types;

- match expenditure profiles to institutional types; and,

- be aware of the financial challenges, driven by declining revenues and increasing costs, facing colleges and universities.

Lesson Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the assignments and readings found in the syllabus.

![]()

Introduction to Revenues and Expenditures

Describing revenues and expenditures within higher education is a daunting task because so much complexity exists. Colleges and universities obtain revenues from a variety of activities and sources, and categorizing those revenues into a manageable number of groups requires you to lump together revenues that are not very similar. Categorizing spending is also not an easy activity, because universities and their employees engage in a variety of activities at the same time, such as teaching, research, public service, and other activities. Trying to determine which dollars go into which categories is almost an impossible task that requires one to make arbitrary decisions.

We could explain these points in greater detail, but you would almost undoubtedly fall asleep before we finished that explanation as this material is very dry and technical. Some of you may have even found the previous paragraph to be a bit sleepy!

Consequently, we will paper over these complexities and just focus on major points reflecting revenues and expenditures. Because we will be presenting data reported by schools to the federal government through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data Systems (IPEDS), we will use the categories employed by IPEDS to categorize revenues and expenditures.

![]()

Institutional Revenues

When summarizing revenues for individual higher education institutions using IPEDS data, the federal government uses the following categories, which summarize the main sources of revenues for many schools fairly well.

- Tuition and Fees - are the revenues collected from students in exchange for the education that the institution provides. These dollars can come directly from the student or from the government through grant or loan funds provided to the student.

- State Appropriations - are dollars directly provided by the state government to support the activities conducted by the institution. Such funds are typically only received by public higher education institutions.

- Local Appropriations - are dollars directly provided by the local government to support the activities conducted by the institution. Such funds are typically only received by public community colleges.

- Government Grants and Contracts - are dollars received from the government, primarily the federal government, for specific research projects, training, or other activities that the university is conducting on behalf of the government.

- Private Gifts, Grants, and Contracts - are dollars received from private sources (individuals, corporations, foundations) as gifts (i.e. donations) or grants or contracts that provide compensation for specific activities.

- Investment Returns - are the revenues that accrue from investments, which are typically contained within a school’s endowment. Endowments contain past donations, and an institution will spend 4-6% of its total value each year to support a school’s operation. Because endowments comprise investments, the value of the endowment fluctuates with the health of the economy.

Let’s turn to data for specific institutions so you can gain a sense of how colleges and universities vary in their reliance upon these different categories.

We will start with Harvard, which is an outlier as it tops the rankings of largest endowments, with a figure of $38 billion in 2018. As a result, investment returns comprise a major share of revenues at Harvard, with the university also drawing substantial funds from private gifts, governmental grants, and tuition and fees. Other private research universities would also rely upon these four revenue categories, but the share coming from their endowment would be much smaller than it is for Harvard.

Figure 3.1 - Revenue Profile, Harvard University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Let's now compare a private research university like Harvard with a public research university. We present data below for Purdue University, which is similar to Harvard in that it obtains a substantial amount of its revenue from investments, tuition and fees, private gifts, and governmental grants. The three primary differences between Harvard and Purdue are differences that are common between private and public universities: (1) Investment returns at Purdue comprise a smaller share which is caused by public universities having smaller endowments than private universities. (2) Tuition and fee revenue comprises a larger share at Purdue which can occur because despite charging lower tuition, public universities enroll a much larger number of students than private universities. (3) Purdue University receives 18% of its revenue from state appropriations while Harvard University, as a private institution, does not receive state appropriations.

Figure 3.2 - Revenue Profile, Purdue University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Let’s now turn to private liberal arts colleges, for which we will use revenue figures for Bethel University. As you can see, the school receives no state appropriations (at it is a private institution) and very little governmental grants and contracts (as liberal arts colleges engage in little grant-funded research or training-based contracts). Bethel receives most of its revenue from tuition and fees, and schools in this situation are often referred to as tuition-driven institutions. The only other meaningful revenue categories are private gifts and endowment returns. Liberal arts colleges with very large endowments, such as Williams College, can rely on investment returns and gifts for major portions of their revenue, but most colleges are like Bethel in that they rely primarily upon tuition and fees to pay their bills.

Figure 3.3 - Revenue Profile, Bethel University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

We now turn to revenue figures for Eastern Michigan University, a public institution with a Carnegie classification of a Master’s university. Eastern Michigan differs from Purdue in that it receives a small amount of investment returns and private gifts, grants, and contracts, as these funds are typically small at publics that are not well-known research universities. Eastern Michigan primarily receives its revenue from tuition and fees, state appropriations, and private gifts, grants and contracts. Michigan is a state with relatively low levels of state appropriations and high tuition and fees, so schools in some other states would have a greater share of state appropriations and a smaller share of tuition and fees than you observe below.

Figure 3.4 - Revenue Profile, Eastern Michigan University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Let’s now examine a community college by examining the below figure for Cuyahoga Community College (OH). Public community colleges are different than other institutions in that they meaningfully rely upon appropriations from their local government, which reflects their emphasis on their local community. Community colleges also receive appropriations from their state, funding from governmental contracts, and tuition and fees dollars. The latter category will never be especially large for community colleges as these schools traditionally have lower prices than other institutions.

Figure 3.5 - Revenue Profile, Cuyahoga Community College, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

The final institution we will examine is the University of Phoenix, a for-profit institution. As you see below, the revenue profile of for-profits differs radically from not-for-profit institutions. For-profit institutions receive almost all of their revenues from tuition and fees and sales and services of educational services. (You should remember that tuition and fee revenue includes dollars from governmental financial aid programs that students use to cover tuition, so even though governmental funds are not named in the below revenue categories, they are an important provider of funds for for-profit institutions.)

Figure 3.6 - Revenue Profile, University of Phoenix, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

![]()

Institutional Revenues: A Self-Check

Now that you have a basic understanding of how revenue patterns vary across institutional types, let’s see if you can successfully match schools with their revenue profiles. Below, you will find a list of schools of very different types and a number of revenue profiles.

![]()

Institutional Expenditures

Describing where colleges get their money is much easier than describing how colleges spend their money. Higher education institutions jointly produce a lot of different items as they educate students, conduct research, and perform public service, with each of these activities requiring a lot of different tasks. For example, the education of students requires direct instruction, out-of-class learning opportunities, advising, counseling, student conduct hearings, financial aid assistance, orientation, and a variety of other tasks.

To describe spending, you need to assign specific costs to specific activities, and because most of the costs of colleges reflect salaries to employees, you essentially need to assign people to specific activities. That task, however, is not always straightforward. For example, the full-time faculty in the higher education program engage in research, instruction, advising, recruitment, admissions, general administration, and public service. What percentage of each faculty member’s salary should be assigned to each of these tasks? No clear answers exist to this question, so colleges and universities are forced to make arbitrary assumptions when assigning personnel costs to activities. When you examine differences across colleges and universities in how much they spend on certain activities, part of the differences across schools reflect differences in the assumptions that schools make when assigning personnel costs to activities. Consequently, one is never sure whether the differences across schools reflect real differences in how they operate or reflect differences in how they calculate their costs.

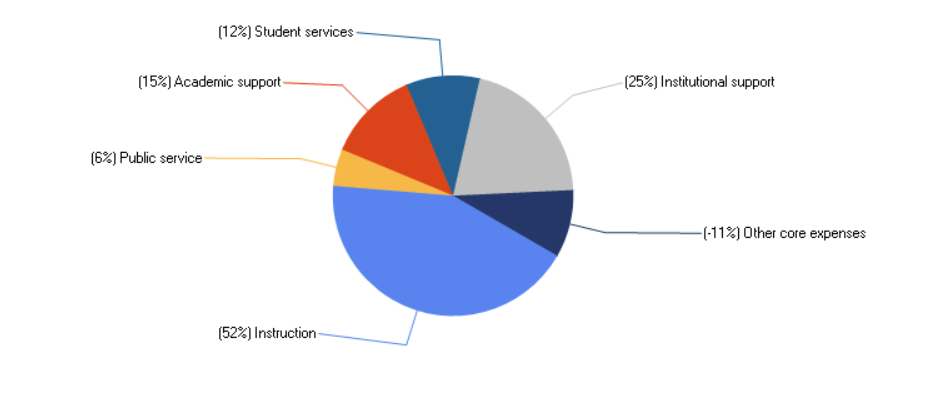

Complicating the analysis is that the true differences across higher education institutions in their spending patterns is not that large. As you can see from the below expenditure figures, the not-for-profit institutions vary little in their spending patterns. Several of the differences that do exist likely reflect true differences in how the schools operate. For example, the figures reveal that the two research universities, Harvard and Purdue, spend around 20% on research while the other institutions spend very little. The figures also reveal that the the public institutions spend more on public service than the private institutions. Other differences, however, may simply reflect differences in accounting patterns. This latter explanation may explain some of the differences across schools in academic support, institutional support, and student services.

For-profit universities use different accounting rules, so the listed categories for for-profit schools aggregate across multiple categories that were used for the not-for-profits. The most striking finding for University of Phoenix is that only 19% of expenditures were on instruction, which likely reflects lower salaries paid to instructors and greater dollars spent on advertising. Not all for-profits, however, spend to the same degree on advertising, so the results observed for the University of Phoenix may not hold for all for-profits.

Figure 3.7 - Expenditure Profile, Harvard University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Figure 3.8 - Expenditure Profile, Purdue University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Figure 3.9 - Expenditure Profile, Bethel University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Figure 3.10 - Expenditure Profile, Eastern Michigan University, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Figure 3.11 - Expenditure Profile, Cuyahoga, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Figure 3.12 - Expenditure Profile, University of Phoenix, Source: IPEDS (U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics.)

Definitions for Expenditure Categories

- Instruction: Activities directly related to instruction, including faculty salaries and benefits, office supplies, administration of academic departments, and the proportion of faculty salaries not going to departmental research and public service.

- Research: Sponsored or organized research, including research centers and project research. These costs are typically budgeted separately from other institutional spending, through special revenues restricted to these purposes.

- Public service: Activities established to provide noninstructional services to external groups. These costs are also budgeted separately, and include conferences, reference bureaus, cooperative extension services and public broadcasting.

- Student services: Noninstructional, student-related activities such as admissions, registrar services, career counseling, financial aid administration, student organizations and intramural athletics. Costs of recruitment, for instance, are typically embedded within student services.

- Academic support: Activities that support instruction, research, and public service. These include libraries, academic computing, museums, central academic administration (deans’ offices), and central personnel for curriculum and course development.

- Institutional support: General administrative services, executive management, legal and fiscal operations, public relations and central operations for physical plant operation.

![]()

Institutional Expenditures: A Self-Check

Let’s now see if you can match expenditures to specific institutions like you did for revenues. This task will be more difficult because expenditures do not systematically vary across institutional types as revenues do. So, do not worry that you are missing important points if you are unable to distinguish between several schools.Leading experts might also have difficulty scoring 100% on the self-check. The challenging nature of this self-check is one of the lessons we want you to retain from our discussion of institutional expenditures. You should always scrutinize cost analyses that make comparisons across institutions (or departments within an institution) to make sure the differences reflect real differences in operations rather than differences in measurement or other factors.

![]()

Why are colleges facing financial difficulties?

To introduce you to the financial challenges facing colleges and universities, let’s watch a segment from Declining by Degrees that examines the financial challenges faced by the Community College of Denver, Western Kentucky University, and the University of Arizona. As you see from the interviews with the presidents of each institution, institutional leaders spend a considerable amount of time contemplating the financial challenges they face and seeking to take action to alleviate those challenges. As we noted at the beginning of the lesson, although financial concerns are not a primary goal of not-profit higher education institutions, they are a central concern because the primary goals cannot be achieved unless sufficient financial resources are available.

We really need you to help us out.

JOHN MERROW: President Christine Johnson is facing challenges of her own. The money CCD gets from the state has been reduced 30%. At the same time, her enrollment was increasing 30%.

What keeps you awake at night?

CHRISTINE JOHNSON: Budgets. Just saying, OK, where do I cut? Who do I cut? And the impact that it has on both the students and the services we'll provide them, and the individuals whose lives will be impacted by that decision.

KAY MCCLENNEY: State policymakers, in a crunch, look around, and say, who can we cut? And the answer often is higher education, and particularly because they see higher education as being the one entity that has the ability to raise revenue on its own through increased tuition and fees.

JOHN MERROW: The disappearing social contract has also hurt colleges, not just students. Nearly every state now gives its public colleges fewer dollars per student, meaning presidents have to find money elsewhere.

GARY RANSDELL: You better either be in a campaign, or finishing one up, or in one, or planning one, if you're going to survive in higher education today.

JOHN MERROW: Since 1999, the cost of running Western Kentucky University has increased nearly 70%. Enrollment has jumped 28%. During that same time, however, the state has reduced the amount of money it provides per student.

How much of your time do you spend fundraising-- thinking about fundraising?

GARY RANSDELL: Thinking about it or doing it? Thinking about it, oh boy, most of the time. 35%, 40%.

PETER LIKINS: The state taxpayer support for public universities is eroding. That creates financial stress that we all understand. And we just manage it. We just deal with it the best we can.

JOHN MERROW: The Arizona legislature has cut Peter Likins's budget nearly $50 million in four years. Today, less than 30% of the university's annual budget comes from the state.

PETER LIKINS: In order to compete successfully, you have to be able to raise gift money. And we've raised over a billion in this recent campaign.

![]()

Why are colleges facing financial difficulties?: The revenue-based portion of the story

The challenges noted by these three presidents are not specific to these schools. In late 2019, Moody’s Investor’s Service issued a negative outlook for the higher education sector due to across the board pressures on all of the revenue sources used by higher education institutions. For the vast majority of higher education institutions, revenues primarily come from two sources: the government and students.

Let’s take a moment to contemplate why revenues are unlikely to increase and may even decrease from these two sources.

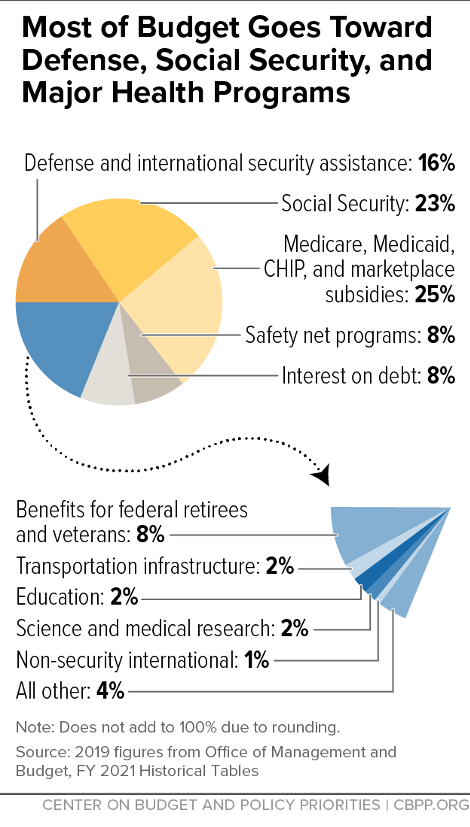

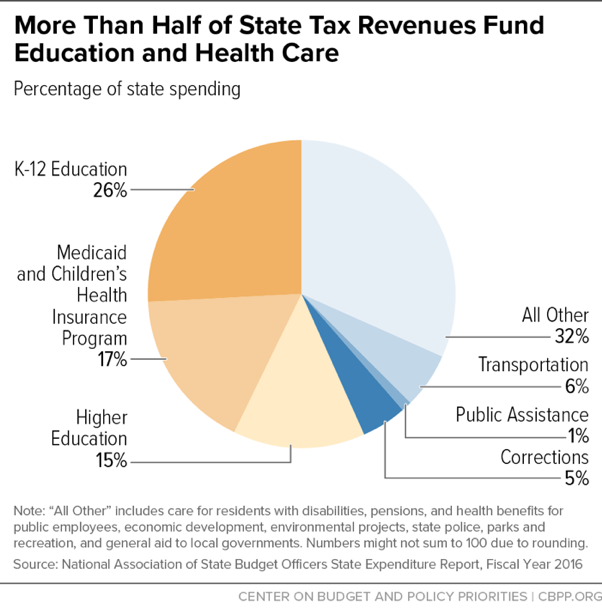

Within the United States (and in many other countries), the financial outlook for state and federal governments are troubling. Before we explain why most outlooks are bleak, let’s quickly introduce you to the budgets for the federal and state governments. See the two figures provided from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities which describes these figures in more detail for both the federal and state.

The first figure shows that most of the spending by the federal government goes to social security, health care (e.g. Medicare), defense, safety net programs, and interest on the debt. Education comprises a very small part of the federal government at 2%. Higher education makes up a larger portion of state budgets at 15%, slightly less than the amount spent on Medicaid, another program providing health care.

Now that you are thinking about governmental spending on higher education with pie charts in mind, let’s explain the governmental funding challenges by noting several points relating to the size of the overall pie and the share of the pie associated with each individual slice of the pie.

Point #1: Governmental revenues are unlikely to increase.

[This slice of the pie is unlikely to increase.]

Explanation: Voters, especially those who vote in Republican primary elections, have punished many politicians in the past who have sought to increase taxes, so many politicians are very resistant to tax increases.

Point #2: Spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security is likely to grow.

[The slices of the pie associated with Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security will grow and form a larger share of the pie.]

Explanation: Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security are entitlements, which means spending on them will automatically grow (unless laws are changed) when more citizens qualify for these services. Because people are living a longer number of years and the baby boom generation is reaching retirement age, more citizens will qualify for these services. Voters, especially those who vote in Democratic primary elections, have punished many politicians in the past who have sought to change the law so less is spent on these services, so many politicians are very resistant to proposing such changes.

Point #3: Spending on higher education is likely to decline.

Explanation: If the size of the overall pie does not grow and certain slices do grow, then the other slices of the pie will need to shrink. Higher education is just as, if not more, likely to shrink as other spending categories as the public has become increasingly comfortable with college students covering an increasing share of their costs through tuition.

As the share of governmental spending that has gone to higher education has declined, many public higher education institutions have increased tuition and fee levels in order to replace governmental funds. Those increases will be described in lesson 11, so we will not cover them in depth here. We simply want to emphasize one point about those increases:

They have caused tuition to grow to the point where many schools are unlikely to be able to increase revenue by increasing tuition.

Further increases could lead to a reduction in the number of students who will enroll and/or an increase in the amount of financial aid that colleges and universities provide themselves. Both of these results will mean that although tuition levels would be higher at schools that raise prices, the actual amount of revenue the schools receive may not increase. Analyses often describe this phenomenon as an institution reaching their “price ceiling.”

As you learned earlier in the lesson, some higher education institutions rely upon private gifts and investment returns from past gifts to help cover costs. These sources of revenue, however, cannot solve the financial problems facing higher education. As you saw earlier when you compared the revenue profiles of different schools, only a subset of higher education institutions receive large amounts of funding from private gifts and endowment returns. Furthermore, donations are not projected to increase by close to the amounts needed to address the financial challenges facing higher education.

Because higher education institutions are unlikely to be able to increase their traditional revenue streams, many have sought to engage in new activities that generate revenue. The big question regarding these activities lies with whether they are mission-enhancing, mission-neutral, or detracting from the institution's mission. Many colleges and universities have created new educational programs that provide education through blended or online formats, which allows the school to expand enrollment. Such activities align with the traditional mission of the institution and simply provide education through new formats. Other activities, however, do not advance mission and could even detract from attempts to meet goals (See The Chronicle of Higher Education Article: Battle Over Colleges and Credit Cards Reaches Showdown in Iowa). For example, some arrangements between credit card companies and universities have been heavily criticized as enriching universities while encouraging students to go into debt. The individuals leading and working within universities who can identify and successfully enact activities that generate revenue while also advancing the mission will be in high demand as the financial challenges facing the industry continue to mount. The amount of entrepreneurial opportunities are not large enough to sustain all colleges and universities, but they may be sufficient to solidify the finances of a subset of schools.

![]()

Why are colleges facing financial difficulties?: The expenditure-based portion of the story

The revenue challenges just noted are compounded by a number of processes that cause costs within higher education to rise faster than costs in other industries. As a result, the normal processes within colleges and universities require substantial yearly increases in revenue. If revenues do not increase or even fall, then the functioning of colleges and universities can be severely disrupted in ways that promote tension and frustration. The institutional leaders who will thrive in the future will be those who can lead thoughtful discussions about cost control and implement the cost-conscious policies that emerge from those discussions. Those individuals at lower levels who can identify, initiate, and sustain approaches that reduce costs while not harming quality will also become increasingly valuable. To develop those skills, one needs to first understand why costs tend to rise faster within higher education institutions than in other organizations, and we present here several of the most common explanations for this pattern.

Explanation #1: The Revenue Theory of Costs

The revenue theory of costs essentially states that colleges and universities are like cookie monsters. Watch the following two videos, keeping the following question in mind: How many cookies will a Cookie Monster eat?

Question Time

Now that you have seen the videos, let's return to the question: How many cookies will a Cookie Monster eat?

How does the cookie consumption of a Cookie monster relate to revenue theory, you ask? The revenue theory of costs is essentially answering the same question but replacing the Cookie Monster with a higher education institution. In other words, how much will a higher education institution spend? Knowing that colleges and universities are like a cookie monster, how would you answer that question?

Revenue Theory, examined

Of course, Howard Bowen, who proposed the Revenue Theory (RT) of costs in his 1980 book, The Costs of Higher Education, was not thinking about cookie monsters when developing this theory. [Ron Ehrenberg, in his book Tuition Rising, proposed the idea of universities as cookie monsters when making a similar point as Bowen.] Bowen had a much more abstract description of his theory:

[A]t any given time, the unit cost of education is determined by the amount of revenues currently available for education relative to enrollment. The statement is more than a tautology, as it expresses the fundamental fact that unit cost [i.e., the cost of education] is determined by hard dollars of revenue and only indirectly and distantly by considerations of need, technology, efficiency, and market wages and prices. (p. 19)

The basic logic underlying his theory were presented as the five laws of higher education costs:

- The dominant goals of institutions are educational excellence, prestige, and influence.

- In quest of these goals, there is virtually no limit to the amount of money an institution could spend for seemingly fruitful educational ends.

- Each institution raises all the money it can.

- Each institution spends all it raises.

- The cumulative effect of the preceding four laws is towards ever increasing expenditure.

So, just like the Cookie Monster, universities can never be satiated. Bowen’s theory does not, however, imply that the individuals who are working within higher education are greedy as the forces driving the theory can be benevolent attempts to advance excellence and prestige. Student affairs officers advocate for greater spending on campus programming and counseling services, enrollment management officers call for activities that promote retention, faculty request resources that will allow them to produce research that advances society and the institution’s reputation, and other folks throughout the campuses have their own resource requests that could improve important outcomes. The challenge for institutional leaders with limited budgets is to deny many of these requests while keeping people motivated to reach organizational goals. The challenge for others is to recognize the cost implications associated with their attempts to enhance quality and seek to find an appropriate balance between quality and cost.

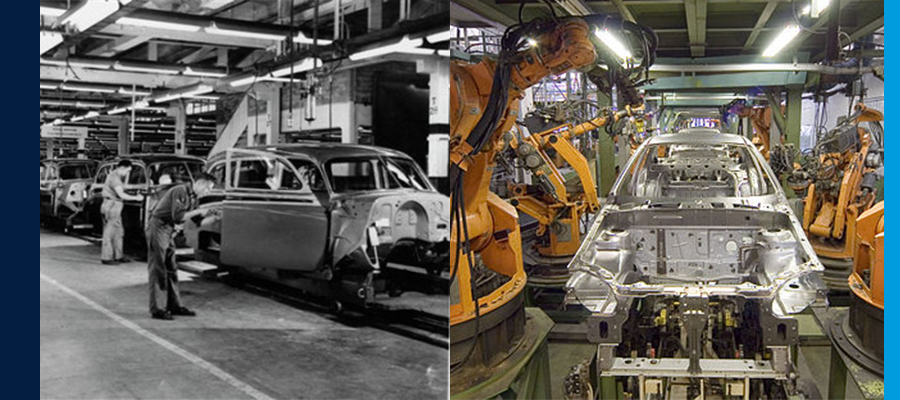

Explanation #2: The Cost Disease

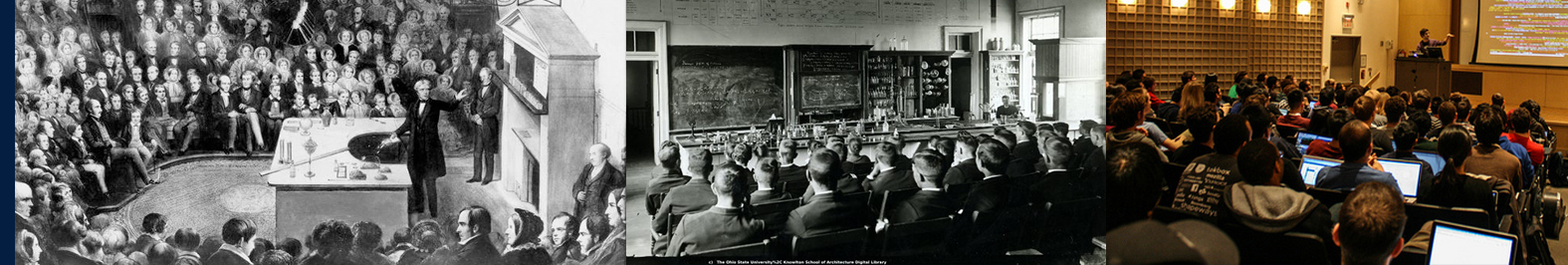

To understand what the cost disease looks like, let’s compare an industry with the cost disease (higher education) with an industry without the cost disease (automobiles). Below you see two photos that show the production of automobiles at various points in industry, with the first picture describing production half a century ago and the second picture describing production recently.

The next set of pictures describes the production of residential instruction within higher education at various points in history. The first picture shows a lecture from 150 years ago, the second shows a similar education scene from 50 years ago, and the third shows higher education today. [We chose pictures of a class with a large number of students, but you can imagine similar scenes for smaller classes by simply shrinking the room and the number of students. There are slight differences in class size across these pictures, but for the purposes of the upcoming questions, you should ignore these differences. Assume that each class has an identical number of students.]

Let us now ask you a number of questions regarding each of these two contexts that will highlight important considerations pertaining to the cost disease.

Questions 1 and 2:

How did the number of workers involved in production of an automobile change over time? How did the number of workers involved in the production of instruction (for a single course) change over time?

Question 3:

How did the use of technology change over time in both of these cases?

Question 4:

How do the required skills of workers change in each of these cases?

Logic of Cost Disease

Let us now combine the answers to each of these questions to explain the basic idea and logic of the cost disease. Industries with the cost disease, like higher education, do not increase productivity growth over time, which means they do not increase the amount produced per worker over time. Consequently, the cost of educating students will not decrease over time and could actually increase if the compensation provided to workers increases over time.

Other industries, like the automotive industry, are seeing large productivity growth, as the amount produced per worker increases rapidly after a robotics-based production line is implemented. The cost of producing each car then falls rapidly. Because the individuals designing and overseeing the robotics are vital to this process, individuals with advanced education and skills, which are needed to design and oversee robotics, become in high demand and subsequently experience salary growth. These salary increases in other industries have implications for higher education, because colleges and universities must compete with other organizations for highly-educated individuals. That competition causes faculty salaries to grow, which leads to rising costs because the amount produced per faculty member is not growing. Those rising costs are the outcome of the cost disease.

To this point, we have primarily thought about the cost disease from the perspective of residential instruction. Other areas of higher education are less affected by the cost disease. For example, course registration used to take place within a large gymnasium filled with employees who met individually with students and helped them register for classes. Today, students register for courses using programs on the internet where humans do not individually assist students and instead simply design and manage registration software. In many ways, registering students is like building automobiles in that humans could be replaced with technology. If higher education institutions are going to reduce costs, then methods must be developed that allow individual workers to produce more than they have in the past.

Other Explanations

Scholars and practitioners have proposed other explanations for rising costs beyond the Revenue Theory of Costs and the Cost Disease. For example, some authors propose that a principal-agent problem exists within higher education, where the agents (faculty, administrators, board members) are not properly focused on the goals of the principals (students, parents, alumni, donors, taxpayers) for whom the organizations are designed to serve. Instead, employees and leaders of the organizations focus on their own goals and interests, which lead to instruction, activities, and research on topics that are of personal interest to employees of the institution but not of great interest to the students and other key principals. These activities often draw narrow audiences and consequently increase the institution’s costs. To address this issue, an institution must develop a culture focused on students, alumni, and other key principals and employ individuals who can identify and regulate the natural human tendency to focus partially on one’s own interests.

Costs can also increase when students, donors, and others desire high-end facilities (e.g., dormitories, recreation centers), winning athletic programs, high rankings, or other items, and universities try to attract those students to their campus by meeting their desires at higher levels than competing institutions. When multiple institutions compete in this way, an arms race can ensue that increases costs at all schools but does not improve the relative position of any institution. Individual institutions will have a difficult time stopping an arms race, as their relative standing will fall if they choose to not participate in the race while others do. Collective agreements across institutions to restrain costs are the best way to address arms races, but such collective agreements are difficult to reach.

By this point, I hope you have healthy appreciation for the many forces that lead costs to rise more rapidly in higher education than in other industries. Colleges and universities are complex organizations, which allows each of these explanations to contain some validity and means that narrow attempts at cost control will likely be unsuccessful. Efforts to restrain costs must be done with care, because the forces propelling costs are also the forces that have promoted the considerable quality that exists within the higher education system. Faculty autonomy, competition across institutions, and the human element of providing education serve valuable purposes. Finding the right balance between cost control and other goals is a difficult task, that will only grow more difficult over time as financial challenges increase.

![]()

Lesson 3 Summary

As financial challenges mount for colleges and universities, financial considerations will play a more important role in the many decisions that regularly occur within higher education institutions. We hope this lesson provides you with a basic understanding of the finances present within higher education and motivates you to consider the financial aspects of the decisions you encounter during your career within higher education. Many who choose to work within higher education choose to do so because they are motivated by mission of instruction, research, and service to society that are central to many institutions and find the more financially focused goals of for-profit organizations to be less compelling. So, the idea of considering financial aspects regularly will not be naturally attractive to many students.

Many important aspects of higher education have a financial component, which makes sense because it typically requires resources to achieve mission. Finance challenges surface in all parts of higher education: concerns around hiring faculty based on expense, barriers to access because of tuition or student debt. As you progress through your career, can you find ways to improve the economic situation of your institution that also advances student learning, improves working conditions, reduces student debt, or meets other goals? That challenge is a great one. We often wish we had a blank check to create policies that will help students or hire the best personnel. We also must be wary of plans that seek to improve institutional finances at the expense of students and employees. The hardest work is to find policies that simultaneously advance mission and financial sustainability. We hope that you leave this lesson more interested in and energized by this challenge than when you entered it.

![]()