HLS801:

Lesson 2: Roles, Responsibilities, Strategy, and Structure of the Homeland Security Enterprise

Lesson 2 - Roles, Responsibilities, Strategy and Structure of the Homeland Security Enterprise

Lesson Overview

This lesson provides a perspective on roles, responsibility, strategy and structure of DHS and others, with an aim of introducing students to the homeland security enterprise and its key elements. In addition, we will examine the art (and science) of strategic thinking, in general, and as it is undertaken by the federal government in responding to threats to U.S. vital national interests. The lesson seeks to prepare students to think strategically, as practitioners, in a frequently changing security environment, by applying frameworks to the analysis of daily incidents, crisis management, and long-term strategies, as applicable. The current challenges to homeland security call for the use of such a process of comprehensive, integrated planning by decision makers in the enlightened pursuit of national objectives, using all the instruments of statecraft, and other capabilities, in a prioritized manner, while considering the vulnerabilities of the United States and always being mindful of the basic beliefs and ideals that are valued by the United States. Lastly, the lesson introduces the students to various leadership principles and traits to consider for the development of (or modification of) the students’ own leadership styles.

Lesson Objectives

At the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Describe the major roles, responsibilities and strategies of DHS

- Become familiar with various frameworks for strategic thinking

- Develop a functional framework to use in thinking about homeland security issues

- Develop an ability to interpret, analyze, and evaluate homeland security issues, using frameworks

- Apply a strategic framework to a current homeland security issue or decision

Please complete the assignments and readings outlined on the course schedule for this week.

Roles and Responsibilities of DHS

DHS has a complex and multifaceted role in public policy stemming from its dual imperatives to protect and prevent. Many agencies were brought together to create the modern DHS as we know it today. Each of them has distinct responsibilities for safeguarding our nation and preventing future terror attacks. Customs and Border Protection, Border Patrol, Coast Guard, TSA, Secret Service and many other DHS components are aligned to work together in securing our domestic safety. However, the scope and diversity of the job, the depth and reach of various programs and policies, and the resources needed to execute these programs effectively requires both strategy and leadership.

As we examine the official mission and purpose of these DHS components we must recognize their diverse roles and responsibilities which, when combined effectively, provide a broad network of homeland security functions. Understanding the specific role which each of these components plays inside DHS is critical to understanding how DHS as a whole carries out its daily mission within the homeland security enterprise.

In the following video, former DHS Chief of Staff Christian Marrone - a Penn State alumn - discusses the diverse character of the department and some of its main roles and responsibilities:

(Note: Students who completed the iMPS-HLS Orientation may have seen this video already during the Orientation)

Taking the Department and understanding it, so the Department is, I said, very diverse in terms of mission space. We do everything from Emergency Preparedness to Cybersecurity. We do border security, aviation security. We’re in immigration benefits. We do --- we offer that as well through we grant citizenships and all the variation of that. We do aviation security. So the cornerstone the Department does, is based out of obviously 9/11 the counterterrorism mission. That’s the cornerstone and that’s the cornerstone certainly the Secretary’s priorities is counterterrorism that’ll always be, you know, first and foremost. But along with that counterterrorism you have all these other missions that we have to accomplish. So with that we have, again, a diverse set of components that were brought together that came from a number of different departments and agencies eleven years ago. And they’re finally starting to coalesce together. We’re really starting to see the Department work much more integrated together. That certainly one the efforts we’re undertaking is a better integration of the Department where we’re not so stovepiped and how we do things. With that we have a budget of a 60 billion dollars, it’s the 3rd largest budget in the federal government. 38 billion is our based budget. That comes from appropriated dollars, the remainder comes from fees. So if you have --- anytime you’ve every travelled through an airport and you look at your ticket fees you pay several different fees which help funds TSA in the security they do at the airports. With that said, with that budget it sounds like a lot of money but given the mission set we have to accomplish its challenging at times and the fiscal environment has not gotten any better and continue to be in a rather austere budget, federal budget environment. With that said, we in the Department goes through a rather vigorous budget process. We’ve established since Secretary Johnson has taken office. And the process is somewhat similar to what DOD goes through; a tried and true process since Secretary McNamara put in places the program and budgeting process. And so that’s one of the key processes that we have here in the Department, and how we fund our components and so components will come forward not just their budgets in stovepipes we did it around issue areas. And so we’ll look at the total budget, total spend that we’re processing in Cyber for instance. And so, in Cyber you’ll have our Protectorate that does Cybersecurity that does, that protects the Dot GOV and helps secure the Dot COM world. Then you have the Secret Service who does a lot of criminal cyber investigations as a part of their portfolio. Then you have some other smaller ones. The Coast Guard as cyber command as part of what they do. ICE has ---- a big part of what ICE does is a human trafficking and so there a cyber-dimension to that as well. So we look at the budget in totally of these key areas. Another key area is on Immigration. So Immigration has a number of different favors to it but Border security is an aspect of, if one can look at that as an aspect of border --- Border security of Immigration. As so we look at how we secure the border and all the aspect around that. So it’s not just the Customs and Border Protection and the Border Patrol that secures the border, the Coast Guard has a piece of that in the maritime domain. Certainly they are doing a lot of drug interdictions and we have immigration illegal migration of through the waterways, you know, through Haiti and Cuba and those places in particular in the southeast part of the United States. In addition to CVP you also have ICE. That ICE does the immigration customs and enforcement. They have part of the border security in the terms of – once ICE --- once CVP apprehend an individual ICE is – takes them into their custody and processes them for removal depending on the circumstances -- will process them for removal. So they’re a part of it. So when you look a border security you don’t just look at any one component. And that’s how we’ve changed the way in which the Department budgets. But it’s challenging given the environment because you fund all the things you like to do--- you have to fund –-- you have to obviously prioritize. So the process that we have set up allows us to be strategic and prioritize. And it’s also helping us integrate these functions better together. So when we do border security we longer just doing border security through the Border Patrol, it’s all these different other organizations and entities within DHS that do that. That’s the value in understanding and the education in the homeland security arena because that’s not readily apparent to--- to--- to most folks about how the Department is operating and changing the way it is operating. It is a dynamic environment now. We’re looking to again do more, better integration of how these components come together. So the budget is one way which we do that. We do a lot of strategic planning with all of our components. So if you’re talking about all the things that we do, the common thread through all of them again is security. And so what aviation --- what we do in aviation security side is not just what TSA does, CVP has a big, big customs and border protection through the Customs side. So anytime you come through --- come international into the United States you get processed through Customs. And that’s a form of aviation security as well on the back end of who’s coming into the country. And so we have pretty robust capabilities of knowing whose coming, where they’re coming from. On the front side, you know, TSA does a lot in terms of the security measures that need to be taken on aviation security so folks--- whose getting on the plane, knowing as much about those individuals to ensure that we – we don’t have bad folks getting on those planes in different locations. And that’s all around the world. Because not everything is just domestic based. And so--- so much of what we do in homeland security is impacted by what happens in other countries. So it’s a very dynamic environment. Then you look at things like what we do with the Secret Service. Again they have a protective mission. The Secret Service every day has a series of protectees including the President and the Vice President. Their job is to maintain their personal security and they do that very effectively. They also have security of the White House. But what most folks don’t understand about the Secret Service is that a critical part of their protectee mission is also their investigative mission. The Secret Service’s field offices all throughout the country which they do a lot of investigations into the financial --- financial crimes. In particular their legacy and how the secret service was started was essential through counterfeit, counterfeit money. Today that counterfeit has taken on a new realm in the cyber realm. And so the Secret Service is along with the FBI they’re the leading national security agencies looking and doing work in the Cyber world on the criminal side. And so the Secret Service does a lot of that and lends itself directly to the protective mission because the protective mission is you just don’t protect the protectee when you go to different cities and different countries you have to have folks to be able to help and expand that protective mission. And the investigative piece allows them to do that when folks aren’t doing the protective mission they’re doing investigative work. And they’re very well thought of in the law enforcement community for what they do. Then you look at --- as we talking about border security, Interior security is what ICE primarily does. They do a lot of the deportation through our removal operations. So the folks who are national security threats, criminals, etc., ICE is the one that go out there and find those individuals, they detain them and deport them. So they have to be heavy handed in terms of the immigration in the Interior. But part of what ICE does also is homeland security investigations, which plays a critical function in support of other law enforcement agencies. So counterfeiting of goods and intellectual property, ICE is there. ICE does a lot of counter-narcotics. They work very closely with the Department of Justice, DEA, ATF, and so you’ll see homeland security investigation out there doing a whole set of things. They are also out there in terms of border security, they’re going after the smugglers of individuals - folks who attempt to smuggle people in. What we find is often when we have an illegal --- illegal migrants don’t come to the border themselves, they come through what they call Coyotes. So ICE and HSSI they’ve been attacking those networks and particular what we experience this summer with the migration of children. There’s your networks there that smuggling these children in. ICE is played a critical role in attacking those networks. And so there a web when we look at homeland security really again a diverse mission, but it all comes together at the end of the day to protect the homeland in one form or another. One of the things most folks do recognize and realize is that FEMA would they do and the critical part of what they do in homeland security mission. So there’s a natural disaster FEMA is the first responder. They’re there, they’re present working with the state and local authorities to respond to be there on the scene and also as part of the recovery. And so that’s a critical function for the federal government; in particular has we’ve seen over the years ---- over the last several years more violent, bigger storms. The last being Hurricane Sandy that caused an enormous disruption to the northeast corridor. And so FEMA had played a critical role, obviously in that, and is critical tool for state and locals in particular Governors and Mayors, etc., as they respond to these. So it’s the federal arm of that.

Strategy and Structure

DHS consists of several components, each with a distinct mission as well as with a mutually supportive mission of sustaining the homeland security enterprise with its own unique activities. In each component there are specific policies and programs which are carried out on a daily basis. Each component has mission requirements has critical operations within the department’s overall objectives.

For a complete overview, see the following listing of all Operational and Support Components that currently make up the Department of Homeland Security.

All of the DHS components contribute, within the vision of "ensuring a homeland that is safe, secure, and resilient against terrorism and other hazards" to realizing the currently six core missions of homeland security (see Department of Homeland Security: "Our Mission", as already addressed in the Definitions section of Lesson 1):

- Counter Terrorism and Homeland Security Threats

- Secure U.S. Borders and Approaches

- Secure Cyberspace and Critical Infrastructure

- Preserve and Uphold the Nation's Prosperity and Economic Security

- Strengthen Preparedness and Resilience

- Champion the DHS Workforce and Strengthen the Department

Some of the operational DHS components to examine include:

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency [CISA]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA]

- Transportation Security Administration [TSA]

- U.S. Customs and Border Protetion [CBP]

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services [USCIS]

- U.S. Coast Guard [USCG]

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE]

- U.S. Secret Service [USSS]

Further, the Secret Service, National Protection Programs Directorate, Domestic Nuclear Detection Office, Science and Technology Directorate, Office of Health Affairs, Office of Intelligence and Analysis, Office of Operations Coordination and Planning and the Office of Policy are all DHS components, and thus parts of the department’s internal structure. In each case the strategies, programs, and policies of each of these components must align themselves with the overall DHS approach towards homeland security and daily coordination to ensure smooth integration of these efforts without overlap, duplication, lapse or error falls on the cabinet agency itself. The components must work collaboratively to share information, leverage resources and develop useful relations with state, local and tribal governments, as well as with key private sector organizations, and work with international partners.

There are several other U.S. Departments and collaborative venues at different tiers of government contributing to realizing homeland security, as explained in the textbook readings for this lesson.

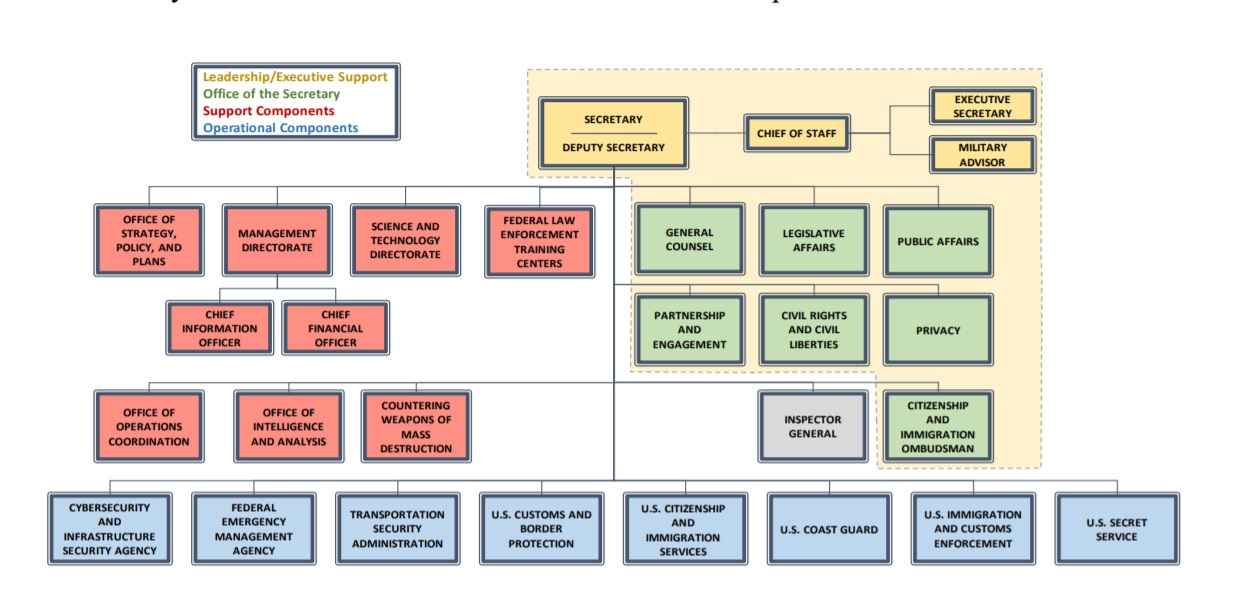

The overall structure and organization of DHS must adhere to a sensible strategy which directs and focuses all of the programs which the department sponsors into a coherent and well organized national effort aimed to enhance domestic protection and preparedness and to enhance the United States’ ability to prevent future terrorist attacks. We understand from the simple elements of the following DHS organizational chart that the sheer diversity of operational missions and the subdivided nature of individual agency activities must work collaboratively, constructively, and in unison:

The reality is that sometimes this does not happen with gaps, errors and shortfalls outweighing any positive or productive achievements which DHS can point to as indicative of its overall success. The President, the Congress and the general public have a right to expect DHS will perform its daily activities within the scope of professionalism and do in ways which actually make the nation more secure and in particular reduce the risks of new terror attacks. We routinely expect this but seldom do we grasp how DHS attempts to do this as it addresses the twin mandate which governs its policies and programs.

The way forward requires sensible policies and programs as well as budgeted resources to match program threats and requirements, staffing DHS with well-educated and skilled personnel, conducting collaborative activities with other federal agencies, state, local and tribal governments, forming useful partnerships with the private sector, energizing and equipping DHS leaders to move the agency forward and the application of strategic thinking. Let’s take a closer look at what strategic thinking entails and requires.

Definitions of Strategic Thinking

In its simplest description, strategy is simply a plan for doing something. In respect to national security and homeland security, it includes the science and the art of employing the political, diplomatic, economic, intelligence related, military, and legal instruments of state (tools of statecraft) to achieve national interests. It describes the way something ought to be done, or that it is proposed to be done. Although the process may appear to be theoretical, it is essential for practitioners to learn to engage in strategic thinking since the mere planning that it encompasses is a useful act, in and of itself, even if it is never utilized. If what was originally considered to be an appropriate course of action suddenly seems ineffective, then the process begins anew by making additional assumptions and arriving at a different course of action.

In the security policy world of making decisions which bear on national interests, the process is constantly ongoing, with each change in one variable causing all assumptions to be revisited. However frustrating the plight of the national or homeland security strategist may appear, the consolation is that there will always be a demand for creative thinking, at least for the very foreseeable future. One of the main decisions of the 9/11 Commission was that there was a failure of imagination on the part of those charged with thinking about security. One perspective on this observation is that leaders failed to imagine the full spectrum of risks and threats facing America at the time and failed to appreciate how realistic or likely those risks and threats might be. It could also entail failures to assess our own capabilities, or our own weaknesses, failure to accurately gauge the mind and intent of terrorist groups and failure to grasp that the global campaign against terrorism would involve several decades of ongoing programs and policies. As overall global threats and risks change over time, we must be watchful that we don’t lapse into the same kind of unimaginative thinking 15-20 years after a seminal event like the 9/11 attacks. As noted, strategic thinking is an art in that it is never predictable in absolutes. As derived from the Greek strategia, it deals with the means being used in various ways to accomplish the ends, often in a prioritized fashion, and subject to the moral orientation of the nation. Strategic thinking is thus a process in which all variables are considered within a framework or structure.

Such a framework for a nation’s plan to ensure its security might consist of the following sets of inquiries:

- Assumptions about the environment, domestically and globally

- Assessment of the national interests (survival, prosperity, values)

- Assessments of threats to national interests

- Analysis of national objectives, modified by opportunities and constraints

- Assessment of national capabilities

- Assessment of national priorities, based on capabilities

- Identification of participants and affected parties

- Assessment of ways to implement desired policies and programs

- Declaration of desired outcomes

- Strengthening the federal emergency response structure

The process of determining what the nation’s goals are, how to achieve them (i.e. what tools of national power are available and how to use them) involves making assumptions, and applying priorities. This is never done in a vacuum or without the consideration of unintended consequences. Thus, the sequence of using means in certain ways to achieve ends is not a linear one, or the product of a rational actor. It is more of a constant measuring of results (or effects), and correcting the course of action, so that ultimately a nation (or strategist) arrives at what is an acceptable outcome to it, at that specific point in time, at a cost which is acceptable under those circumstances. In other words, it is the reality of a nation (or decision maker) arriving at what it is willing to settle for at a price or a cost (compromise), which it is willing to pay (bear or accept). This is an iterative process, which is constantly ongoing, and often manifests itself as a type of conflict management, with resolution remaining in the distant future.

Strategic thinking thus results in much more than a plan or a result that is arrived at scientifically. Strategos entails having a concept, an idea, priorities, and a direction. With such flexibility and imagination, one can adapt and hopefully use a rational and disciplined allocation of resources to achieve objectives.

When we attempt to understand, analyze and codify what strategic thinking really means it requires some in-depth analysis of its component parts. Typically it involves problem solving, analysis, leadership and formulation of alternative approaches. Strategic thinking can be understood in many ways; however, one approach which seems reasonable and pragmatic includes the following ingredients:

- vision and leadership [views and perspectives on desired outcome, objective or end state]

- analysis of critical factors [supporting, enhancing, detracting, shaping, maximizing]

- consideration of alternative pathways [examination of feasible, desirable, difficult avenues]

- developing plans and enacting them [taking risks, executing ideas, accomplishing interval milestones]

- consolidating actions/achieving desired results [confirming fulfillment of objectives, outcomes, end-states]

Exemplary Definitions of "Strategy"

in a synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or

multinational objectives."

Joint Publication 3-0 (JP 3-0), August 2011

John M. Collins, Grand Strategy: Principles and Practices, 1973

Terry L. Deibel, Foreign Affairs Strategy - Logic for American Statecraft, 2007

Other Homeland Security Related Definitions

As we start our journey through this lesson and the course, it is important to identify and define some terms with which the homeland security strategist and practitioner must be familiar. You have already come across some of those definitions in your Lesson 1 textbook readings.

Attribution - assessing or identifying which organization or nation was behind an attack or a terrorist activity (Atlantic Council, "Beyond Attribution: Seeking National Responsibility in Cyberspace" by Jason Healey, February 22, 2012)

Consequence Management (CM) - those actions required to manage and mitigate problems resulting from disasters and catastrophes. It may include Continuity of Operations (COOP)/Continuity of Government (COG) measures to restore essential government services, protect public health and safety, and provide emergency relief to affected governments, businesses, and individuals. Responses occur under the primary jurisdiction of the affected state and local government, and the Federal government provides assistance when required. When situations are beyond the capability of the state, the governor requests federal assistance through the President. The President may also direct the Federal government to provide supplemental assistance to state and local governments to alleviate the suffering and damage resulting from disasters or emergencies. DHS/FEMA has the primary responsibility for coordination of federal CM assistance to state and local governments.” (Homeland Security, Joint Publication 3-26, August 2005)

Deterrence - the prevention of action by the existence of a credible threat of unacceptable

counteraction and/or belief that the cost of action outweighs the perceived benefits. (Joint Publication 3-0) For example, many security experts believe that mere possession of nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them deters over 98% of conventional threats to our security because deterrence rests on assured and targeted retaliation.

Mitigation - the activities designed to reduce or eliminate risks to persons or property or to lessen the actual or potential effects or consequences of an incident. Mitigation measures may be implemented prior to, during, or after an incident. Mitigation measures are often informed by lessons learned from prior incidents. Mitigation involves ongoing actions to reduce exposure to, probability of, or potential loss from hazards. Measures may include zoning and building codes, floodplain buyouts, and analysis of hazard- related data to determine where it is safe to build or locate temporary facilities. Mitigation can include efforts to educate governments, businesses, and the public on measures they can take to reduce loss and injury. (National Incident Management System - NIMS)

Policy - "the statements and actions of government: it is the output of what is often called the 'policy process,' which takes place within and among the departments and agencies of the Executive branch of the federal government and between it and Congress. Strategy ... should be thought of as an input to that process, a guiding blueprint whose role is to direct policy, to determine what the government says and does." (Deibel, Foreign Affairs Strategy - Logic for American Statecraft, 2007, p. 10).

Preemption - the anticipatory use of force in the face of an imminent attack; it has long been accepted as legitimate and appropriate under international law. (Brookings, "The New National Security Strategy and Preemption" by James B. Steinberg, Michael E. O'Hanlon, and Susan E. Rice, December 2002)

Prevention - actions to avoid an incident or to intervene to stop an incident from occurring. Prevention involves actions to protect lives and property. It involves applying intelligence and other information to a range of activities that may include such countermeasures as deterrence operations; heightened inspections; improved surveillance and security operations; investigations to determine the full nature and source of the threat; public health and agricultural surveillance and testing processes; immunizations, isolation, or quarantine; and, as appropriate, specific law enforcement operations aimed at deterring, preempting, interdicting, or disrupting illegal activity and apprehending potential perpetrators and bringing them to justice. (National Incident Management System - NIMS)

Resilience - the ability to adapt to changing conditions and withstand and rapidly recover from disruption to emergencies. (Presidential Policy Directive 8: National Preparedness - March 2011)

Response - activities that address the short-term, direct effects of an incident. Response includes immediate actions to save lives, protect property, and meet basic human needs. Response also includes the execution of emergency operations plans and of mitigation activities designed to limit the loss of life, personal injury, property damage, and other unfavorable outcomes. As indicated by the situation, response activities include applying intelligence and other information to lessen the effects or consequences of an incident; increased security operations; continuing investigations into nature and source of the threat; ongoing public health and agricultural surveillance and testing processes; immunizations, isolation, or quarantine; and specific law enforcement operations aimed at preempting, interdicting, or disrupting illegal activity, and apprehending actual perpetrators and bringing them to justice. (National Incident Management System - NIMS) From a national security perspective, a response may be an action(s) to eliminate current threats and prevent future actions. Responses are required to establish deterrence.

Thinking About Homeland Security Policies and Programs

Homeland security policy and programs are based on certain factors---intelligence, threat information, inherent risk situations, probable attack scenarios, prior experience with terror groups, Presidential preferences and the emergence of new threats to the homeland never before assessed. Some would favor a homeland security policy framework in which the intent of the malicious actor is assessed along with the presumed authenticity of that intent. In turn, that intention is then analyzed in light of capabilities or access to means to do harm and actually deliver on the intentions and threats. At the same time, the degree of vulnerability is considered which entails levels of security and assumptions of risk. Not all potential targets reflect the same level of risk. Finally, an evaluation of all of the aforementioned when combined analytically equals the actual threat, or degree of danger. Once the danger is identified and anticipated, a response in the form of mitigation, prevention, or protection can be considered, as well as proper response and recovery plans. This also depends heavily on knowing when the actual threat will manifest and what the specific target is. Too often, however, we cannot fathom an enemy’s intent, and we are materially ignorant of his capabilities as well as our specific vulnerabilities. One famous political leader has said, “terrorists only have to be right 1% of the time, while we have to be vigilant 100% of the time.”

As we ponder the array of strategic issues which DHS must address and resolve—consider these challenges

- Homeland security vs. national security vs. international security—what balance makes sense?

- Looking at DHS components' strategic plans and goals, which ones deserve highest priority?

- How to best devise strategy, overcome faulty assumptions, deal with unknowns and black swans?

- What does layered defense really mean?

- What mechanisms and insights are crucial for crisis management?

- What is the proper role of the private sector in homeland security?

- What is the collaborative role of the Defense Department when working with the states and DHS?

- What strategies will be adequate to deal with evolving terror threat tactics in the future?

- What planning schemes seem most effective against likely risk, and specific threats?

- What is the proper role of domestic and foreign intelligence?

- What further steps--if any--can be taken to reduce the risks of future terrorist attacks?

The principal risk challenge of tomorrow's threat environment is knowing where and when a future terror attack will take place. This is complex and difficult because we seldom can predict with accuracy what will happen in a few days. Nevertheless, our national approach is to discern the intent of any hostile party, assess its capabilities and interdict or prevent the execution of an attack. If there is hostile intent, and there is perceived or known access to weaponized elements or other offensive instrumentalities, the likelihood of an incident is then measured against the vulnerabilities of the targeted nation or individuals. If there is a real likelihood that the actor is able to engage in a malicious act and the target is vulnerable, the question becomes how much risk is tolerable? The same thought process must be applied to potential natural disasters as well. However today we must also contend with the radicalized homegrown violent extremist [HVE], the disaffected insider and foreign agents dwelling among us in quiet and low key situations which some regard as ‘sleeper cells’. In addition, we must be vigilant about those who have slipped inside the country illegally and who are awaiting the opportunity to attack.

So this poses several challenging dilemmas which will confront DHS and national security experts in the years ahead. Those include:

- Will there be another massive high casualty attack on one of our cities?

- Will there be a series of small-scale attacks against soft targets?

- Will terrorists prefer a cyber attack over a more conventional armed attack?

- Will the United States adopt an armed targeted retaliation policy for future terror attacks?

- Will the United States have to sustain and support an allied coalition indefinitely to defeat or neutralize terror groups?

Whether the actor is man or Mother Nature, the statement made by President Bush in the July 2002 National Strategy for Homeland Security focusing on risk (although his focus was on terrorism) rings true today: Because we must not permit the threat of terrorism to alter the American way of life, we have to accept some level of terrorist risk as a permanent condition. We must constantly balance the benefits of mitigating this risk against both the economic costs and infringements on individual liberty that this mitigation entails. No mathematical formula can reveal the appropriate balance; it must be determined by politically accountable leaders exercising sound, considered judgment informed by top-notch scientists, medical experts, and engineers. Again, how much risk is the homeland security strategist willing to accept?

Thinking Strategically About Protecting the Homeland and the Nature of the Challenge

The narrative of Homeland Security is one of great complexity, requiring an historical perspective and a strategic approach. Its treatment goes to the core purpose for the founding of the nation and the basic mission of the government. The application of all resources of the state (i.e., the federal government) must be brought to bear on the nation’s survival, prosperity and values. Such deliberations require that the decision makers engage in strategic thinking at the highest level possible, making the best possible assumptions about the geopolitical environment and choosing priorities as to what the nation, can, should, and must do when confronted with a homeland security issue.

In taking a strategic overview of the context, there is empirical knowledge about the players and the processes, ethical and moral considerations, leadership, and a sense of vision which affect the direction of the policies, its relevance to our lives and our security. The stakes are, of course, very significant: the existence and safety of the nation and its citizens; the free flow of persons and ideas; the balance between security and privacy; and, the preservation of freedom.

Ultimately, this lesson, and this course, are not about teaching empirical knowledge, or trying to address all the data pertaining to homeland security. Rather, they are about teaching how to think about protecting and assisting all aspects of a society, before, during and after a catastrophic event or disaster. Thus, the strategist must be aware of the many variables and develop a knowledge base, and ultimately the wisdom to do the right things well! The consummate practitioner must sense where to find the center of gravity in an issue and how to learn what he or she does not know.

There are various categories of issues associated with strategic thinking about homeland security:

- Security issues requiring strategic thinking and a plan to mitigate, prevent, protect, respond and recover.

- Emergency or crisis management issues requiring strategic thinking and a plan to mitigate, respond, and recover.

- Societal issues requiring strategic thinking and a plan to preserve justice, values, the economy, and culture.

- Government issues at all levels (federal, state, and local) requiring strategic thinking and a plan concerning organization, policies, and global relations.

There have been several instances when the United States has developed successful strategies to respond to challenges, from wars to economic crises. The Cold War strategy continued for 50 years, while the plan (within that greater context) to prevail during the Cuban Missile Crisis lasted less than two weeks. The newest set of challenges associated with terrorism may become another long campaign which could take decades to resolve.

Current Strategies and Paradigms of Homeland Security

When confronted with the threat of the escalation of terrorism since the 9/11 attack, the U.S. strategy has been to take the offense in Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries that either support terrorism, or harbor and support terrorist groups. The strategy for homeland security has thus been partially focused on preempting terrorism before it has a chance to occur. This threat-based counter-terrorism strategy has three elements: stopping terrorists we know about, trying to stop terrorists we don’t yet know about, and discouraging people from becoming terrorists. The challenge has been to learn which state supported and non-state supported terrorists are as a prerequisite to understanding the threat. At the same time, gaining an understanding of U.S. vulnerabilities and eliminating or reducing them, has also been the approach for defending the homeland, regardless of the identity or the intent of the bad actors. Making a potential attack too risky or forcing a potential terrorist to consider a target of significantly lower ‘value’ may thwart a potential attack, or certainly a more serious one.

Accomplishing the above goals of taking the initiative to the terrorists while reducing vulnerabilities has required a comprehensive security strategy – a National Strategy for Homeland Security (2007) that includes elements of mitigation, prevention, protection, and response. In reaction to natural disasters, specifically Hurricane Katrina, it applies an all-hazards approach.

Trying to find the center of gravity in the strategy for homeland security has resulted in a strategic cycle from prevention to recovery. Preventing an attack from occurring through diplomacy and other policies to reduce or eliminate factors which spawn terrorism, through the effective use of intelligence regarding a potential threat, and the use of law enforcement against the potential acts are initial, yet difficult, steps. Beyond that, there is a need to protect critical infrastructure, such as airports, airways, water supplies, bridges, and key buildings at all levels. At the same time, there is a need to respond to any attack in order to minimize loss of life and limit further damage to infrastructure. This approach to decision making has become so important that it is part of the Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR), in which assumptions and variables are discussed.

The evolving organization of participants involved in some aspect of homeland security is an aspect of the U.S. form of governance. The Department of Homeland Security, the Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism, the Director of National Intelligence, the National Counter Terrorism Center, and the U.S. Northern Command are all new participants at the federal level in a homeland security strategy centered on prevention, protection, mitigation, repsonse, and recovery. Although all agencies are charged with strategic thinking, the Department of Homeland Security has been given the lead and has set about that responsibility with great energy. By comparing the 2010 with the 2014 QHSR and beyond, reviewing this lesson's readings, we can see shifts in orientation and overall policy emphasis.

Intangibles in Strategic Thinking that Make a Difference

Ambiguity, chance and change:

As with all strategy, there is a need for homeland security practitioners to have the patience and judgment to deal with ambiguity and change. Often it is essential to manage the issue with perseverance, since resolution often takes great time and patience. Consider the following steps which make for effective decision making:

- When confronted with a homeland security issue, how should one proceed?

- What are some of the threshold issues a strategist faces?

- How does one learn to ask the right questions?

- What assumptions can one make about the environment?

- What constraints apply?

- Can one act, should one act, MUST one act?

- If action must be taken, what controlling authorities apply?

- Does the Constitution even address government action in this instance?

- Are there Statutes or court decisions that restrict the use of instruments or other actions?

- Are there policy considerations that make for inconsistencies?

- If all of the above questions are satisfied, then what instruments of the state shall be brought to bear and in what ways and for how long?

This calls for new thinking and a revised strategy which will undergo public and political pressures where new programs and policies will likely be unveiled. The strategist’s answers to the above questions will make the difference between successes and failures, perhaps between conflict management and conflict resolution. The urgent issue is how to define 'success' in preventing and protecting against terrorism, as well in all-hazards focused strategic efforts.

Risk Management

An element of every strategy is the degree to which the decision makers assume some degree of risk on behalf of those for whom they are making the decision. As already pointed out in the National Strategy for Homeland Security of 2007, when focusing on risk (albeit terrorism), "we have to accept some level of terrorist risk as a permanent condition..." Zero tolerance, or the avoidance of all risk, may be the goal, but other variables often make that end state unrealistic, and some risk may be preferable to the price of getting to a state of no risk. Discussions in this area often resort to the decision to live with low probability, high consequence threats versus high probability, low consequence results. The acceptance of risk and the planning for it have manifested themselves in recent strategies as the ‘new norm’ of awareness of the consequences, and of resilience in the event there is an incident.

Risk management requires a delicate balance between what makes sense, seems proven and is reliably understood and engaging instead in new and untried behaviors and strategies in pursuit of shaping different outcomes and results. The tradeoffs between what is familiar and comfortable with what is unproven and risky cannot be calibrated solely by experts and political leaders without input from ordinary citizens. There must be a shared commitment towards investing in a risk management strategy that sustains our society well past 2020 and reflects new imperatives about how best to ensure our collective homeland security.

Summary and Wrap-Up Activity

The above activities are for your additional individual advancement in this course and will not be logged or graded.

Knowing the key roles and responsibilities of DHS and the homeland security enterprise is important but this does not operate in a vacuum. There is a need for coherent and relevant strategy to deal with ongoing terror threats which can shape the agency and the enterprise for new and emerging threats. The structure, operations, policies and programs which DHS exhibits are meant to reflect continuing demands and requirements from Congress, the President, the media, the public and the overall threat environment as DHS understands it.

Strategic thinking is essential to ensure a successful homeland security strategy. Although there is no set formula, the application of a framework ensures that the maximum combinations of thought processes and considerations will go into decision making, often in an orderly manner. Becoming a skillful and enlightened practitioner with an awareness of history, and the context of security, comes from the analysis of countless scenarios, and perhaps could even result in a degree of wisdom, a too seldom evidenced attribute, but one on which this introspective lesson should end.

To wrap up, go to the Navigate 2 Companion Website for your textbook and use the following nuggets to wrap up this lesson:

- Review definitions and key terms in the Glossary for Chapters 4, 5, and 6 (use "Search by Chapter" to generate the chapter-specific list of terms).

- Work with the Flashcards for Chapter 4 in order to consolidate your learning of important key terms.

- Work with the Flashcards for Chapter 5 in order to consolidate your learning of important key terms.

- Work with the Flashcards for Chapter 6 in order to consolidate your learning of important key terms.

- It is also recommended you test your knowledge further by completing the Chapter Quiz for Chaper 4.

- It is also recommended you test your knowledge further by completing the Chapter Quiz for Chaper 5.

- It is also recommended you test your knowledge further by completing the Chapter Quiz for Chaper 6.

Executive Leadership

An enlightened practitioner charged with the safety of the nation and its citizens as well as their rights (those values articulated in the Declaration of Independence and incorporated into the Constitution) takes an oath to the Constitution and serves in a fiduciary relationship to the people. That oath obliges the taker to support and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic, and to bear true allegiance to the Constitution. Leadership skills are required to inspire others to act at the highest standard possible to assure the pursuit of those strategies which are for the greater good. Guidelines are amply available to assist in learning leadership beyond those attributes which most decision makers bring to the table.

EO 13434 -- National Security Professional Development addressed the intent by the President George W. Bush administration to develop a corps of national security professionals. The program was but one formula to bring about greater leadership. A key tenet was that critical thinking is a core competency of service at any level of government or society. While EO 13434 did not gain traction with the Bush or the Obama administrations, it points to the fact that professional competence is a moral imperative.

Truly enlightened leadership means doing something well not only because one’s career or life depends on it, but because it is for the greater good. And, it means not just doing things right, but doing the right things. As a public servant, there is a requirement to act ethically and conserve resources. When vital national interests of the nation are involved, then the responsibility is at its greatest.

The Architecture of Leadership offers a compilation of leadership skills for consideration, reflection, study, and use in an individual’s leadership tool kit. One of the authors, Admiral James Loy, U.S. Coast Guard (retired), who was a former deputy secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, the former Head of the Transportation Security Administration, and the former Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, is uniquely qualified to discuss leadership at all levels – from the tactical level (small unit) to the strategic/executive level. Admiral Loy, and his fellow author, Donald Phillips, study great leaders of the past and present common elements that may be utilized to constitute an architecture of leadership. As the authors note in the Afterword, “…The Architecture of Leadership … works for any individual, in any profession, who chooses to become a good leader … The Architecture of Leadership can also be used as a template for organizations that wish to foster better internal leadership. It can also be employed to create a solid leadership organization from scratch – one that will last, one that will stand the test of time.” Hopefully this text will help further develop and refine enlightened executive leadership that is needed by all public servants.

The book Philips, Donald T. and James M. Loy: The Architecture of Leadership: Preparation equals Performance. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008, is optional reading.

The presentation by James M. Loy on "The Architecture of Leadership" at the Third Annual DHS University Network Summit,

March 17-19, 2009 is required leading for this lesson and summarizes the main argument of the book.

Without doubt leadership is essential in our Congress, our political leaders, our senior Cabinet officials, our local mayors and city councils. Taking our security for granted provides no assurance that our way of life is truly protected and citizen involvement in shaping our nation's policies against terrorism will require sustained engagement and support.

Risk Management

An element of every strategy is the degree to which the decision makers assume some degree of risk on behalf of those for whom they are making the decision. As already pointed out in the first National Strategy for Homeland Security of 2002, when focusing on risk (albeit terrorism), "we have to accept some level of terrorist risk as a permanent condition..." Zero tolerance, or the avoidance of all risk, may be the goal, but other variables often make that end state unrealistic, and some risk may be preferable to the price of getting to a state of no risk. Discussions in this area often resort to the decision to live with low probability, high consequence threats versus high probability, low consequence results. The acceptance of risk and the planning for it have manifested themselves in recent strategies as the ‘new norm’ of awareness of the consequences, and of resiliency in the event there is an incident, and attention must of necessity be directed to the recovery phase.

Risk management requires a delicate balance between what makes sense, seems proven and is reliably understood and engaging instead in new and untried behaviors and strategies in pursuit of shaping different outcomes and results. The tradeoffs between what is familiar and comfortable with what is unproven and risky cannot be calibrated solely by experts and political leaders without input from ordinary citizens. There must be a shared commitment towards investing in a risk management strategy that sustains our society well past 2020 and reflects new imperatives about how best to ensure our collective homeland security.