HLS832:

Lesson 2 - The Department of Defense in Context

Introduction

Lesson Objectives:

-

Summarize the impact 9/11 had on how DOD thinks about homeland security, HD, and DSCA, as well as its more “traditional” pre-9/11 roles, missions, functions, organization, and capabilities.

-

Describe the unique American values, laws, culture, and traditions that guide the employment of the U.S. military in the homeland.

-

Explain the opportunities and challenges that remain regarding the maturation of the homeland security enterprise and DOD’s place in it.

-

Explain the basic organizational structure of DOD and how it coordinates critical support operations in response to an incident with other U.S. Government agencies; state, local, and tribal governments; intergovernmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector.

-

Identify the U.S. Northern Command’s roles and responsibilities within the Unified Command Plan.

Please complete the assignments and readings outlined on the course schedule for this week.

The U.S. Military in the Homeland: An Indispensable Partner in the Emergency Response Enterprise

Joint Publication

-

U.S. Government agencies;

-

State, local, and tribal governments;

-

International organizations;

-

Governmental organizations;

-

Nongovernmental organizations; and

-

The private sector.

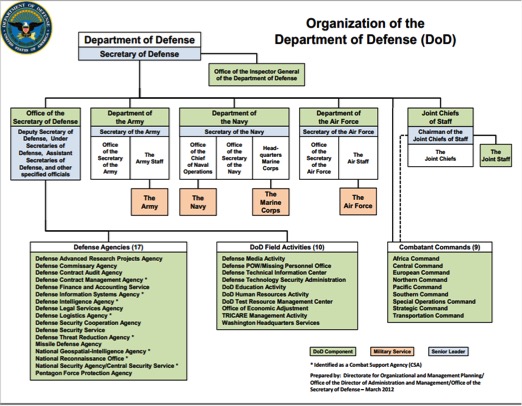

Functions of the Department of Defense and Its Major Components

Organization of the Department of Defense (DoD)

DOD Directive

Thomas Atkin

Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense and Global Security

Tom Atkin is the Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense and Global Security. He is responsible for advising the Secretary of Defense and Under Secretary of Defense for Policy on policy, strategy, and implementation guidance across a diverse portfolio of national and global security issues. These issues include countering weapons of mass destruction, cyber operations, homeland defense activities, antiterrorism, continuity of government and mission assurance, defense support to civil authorities and space-related matters.

Previously, from November 2014 to August 2015, Mr. Atkin served as Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense and Global Security. Prior to his appointment in 2014, Mr. Atkin was a Director for Raytheon U.S. Business Development for Homeland Security. In this capacity he was responsible for linking technological, engineering and service solutions to maritime, border, public safety and other security-related requirements in the homeland security market. Mr. Atkin also served as the Managing Principal of The Atkin Group, a management consulting firm that provided broad strategic and operational counsel on intelligence, maritime security, crisis management, incident response, and interagency coordination to senior government and corporate officials.

Mr. Atkin retired from the Coast Guard as a Rear Admiral (Upper Half) in June 2012 after more than 30 years of service in various operational and strategic roles. He has significant experience across the whole of government and has served in support of the White House National Security Staff, Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), U.S. Coast Guard, and U.S. Navy. His senior leadership positions included serving as Assistant Commandant for Intelligence and Criminal Investigations; acting Assistant Commandant for Marine Safety, Security and Stewardship; Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Transborder Security on the White House National Security Staff; Commander of the Coast Guard Deployable Operations Group; Deputy Principal Federal Official to the FEMA Gulf Coast Joint Field Office; and Chief of Staff to the Principal Federal Official for Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. His previous Pentagon assignments were Chief, Maritime Homeland Security and Defense Policy, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Homeland Defense; and Chief, Counter-Terrorism Branch, Chief of Naval Operations (Deep Blue).

He is a graduate from the United States Coast Guard Academy with a Bachelor of Science in Mathematical Sciences, and holds a Master of Science in Management Science from the University of Miami.

(Note: Mr. Atkin is Acting as of Sept. 2015).

CRS Report

JOH - Staffing and Action Guide

Insights and Best Practices Focus Paper: Interorganizational Coordination

The Joint Staff, J-7 supports the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Combatant  Commanders, and the warfighter by publishing various focus papers. This one, Interorganizational Coordination (Joint Staff, J-7, 2013) complements your reading of Joint Publication 3-08, Interorganizational Cooperation (Joint Staff, J-3, 2016). JP 3-08 was recently revised from the previous version (Interorganizational Coordination During Joint Operations, 2011). Don’t be too concerned that the J-7 Focus Paper pre-dates the revision of JP 3-08. The foundational concepts are still there and are mutually supporting. You will even see references to the 2011 version of JP 3-08 in the J-7 Focus Paper.

Commanders, and the warfighter by publishing various focus papers. This one, Interorganizational Coordination (Joint Staff, J-7, 2013) complements your reading of Joint Publication 3-08, Interorganizational Cooperation (Joint Staff, J-3, 2016). JP 3-08 was recently revised from the previous version (Interorganizational Coordination During Joint Operations, 2011). Don’t be too concerned that the J-7 Focus Paper pre-dates the revision of JP 3-08. The foundational concepts are still there and are mutually supporting. You will even see references to the 2011 version of JP 3-08 in the J-7 Focus Paper.

All the elements of national power—diplomatic, informational, military, and economic (DIME)—significantly affect U.S. national security in the extremely complex global environment. The United States Government (USG) has observed numerous best practices in how operational commanders and our interorganizational partners work together to achieve objectives. An atmosphere of inclusiveness must be established and is often done so in collaboration with international organizations, governmental organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGO), and the private sector in a whole of government approach. This enables and facilitates bringing together all elements of national and international power to achieve strategic objectives. With that said, effective relationships and coordination with lead agencies (within the USG or otherwise) are key to gaining situational awareness of external stakeholders who can have a positive impact on the mission (Joint Staff, J-7, 2013, p. 1).

There are, of course, challenges associated with unified action and interorganizational coordination. The active participants and other stakeholders recognize that there will not be unqualified unity of command with one single authority nor clearly defined roles and responsibilities. They acknowledge that complete unity of effort is often difficult. Also, interorganizational partners do not have the funding, number of personnel, or the capacity of the U.S. military. Further, their perspectives on a situation, possible solutions, and any agendas can vary widely. Also, there is the very real possibility of encountering friction when working together with different organizational cultures. Interorganizational coordination is just not as easy as one would like it to be (Joint Staff, J-7, 2013, p. 1).

Summary

-

Summarize the impact 9/11 had on how DOD thinks about homeland security, HD, and DSCA, as well as its more “traditional” roles, missions, functions, organization, and capabilities.

-

Describe the unique American values, laws, culture, and traditions that guide the employment of the U.S. military in the homeland.

-

Explain the opportunities and challenges that remain regarding the maturation of the homeland security enterprise and DOD’s place in it.

-

Explain the basic organizational structure of DOD and how it coordinates critical support operations in response to an incident with other U.S. Government agencies; state, local, and tribal governments; intergovernmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector.

-

Identify the U.S. Northern Command’s roles and responsibilities within the Unified Command Plan.

Assignments

Discussion Forum:

- Respond to the Lesson 2 Discussion Forum question by Thursday. (You can also access discussion forums by clicking the "Activities" link in the left-hand navigation bar). Your posting should be articulate and thoughtful - based on your takeaways from this lesson and its assigned readings, yet concise. Include examples from the lesson where appropriate to support your point of view. The discussion forum question is just the starting point for discussion. The key is to add your own insights, experiences, and additional research as appropriate.

- Respond to two of your fellow classmates by Sunday. The objective of the discussion forums is to develop a discussion thread that stimulates critical thinking and in-depth dialogue. Professionalism and common courtesy are expected.

- Question: Why is Interorganizational Coordination so important to DOD and its partners?