HRER501:

Lesson 03: Legal Aspects of Recruiting, Hiring, and Promotion

L03 Overview

In this lesson, we review the application and selection process and what can result in violations of laws despite good intentions. Examples will include methods of recruitment that restrict access based on protected class characteristics (including what defines protected classes), limitations on inquiries concerning medical conditions, and the controversies surrounding employer access to and reliance on social media activity.

We will also review problems that can arise based on employer promises, resulting in breaches of implied or written contracts, and employee misrepresentation of qualification or credentials.

The complex areas of bona fide occupational qualifications (BFOQ), methods of establishing disparate or unequal treatment, and disparate treatment, including reliance on subjective criteria. A point for emphasis is that a BFOQ can never involve a preference based on race.

We will also review affirmative actions programs (AAPS) in terms of what an employer must do to establish a plan that conforms with Title VII and the myriad challenges that can result.

Again, the focus is on preemployment practices and considerations.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

- Explain BFOQ (bona fide occupational qualification) status and requirements

- Evaluate discrimination issues that arise from recruiting processes

- Analyze the validity of affirmative action programs

Reading and Activities

Check the Course Schedule for specific details on what to read this week.

L03 Introduction

In the previous lesson, we looked at bases for what comprises an employment relationship. In this lesson, we review how employment relationships begin as part of a study that will take us to problems that arise during employment – from the perspectives of both the employee and the employer – to an eventual review of how the relationship ends.

Though much has been written about a so-called great resignation from the workplace, not as much attention has been accorded the inevitable rebound. Work is a significant part of most lives. People start jobs or businesses with expectations, hopes and goals. Some careers go smoothly. Some do not.

No matter how the trajectory develops, finding a job requires knowledge that one is available. Forms of notice include word-of-mouth, internal postings, online sites, professional publications, headhunters, newspapers, social media, college placement services, job fairs, employment agencies, union hiring halls, bulletin boards, and the low-tech sign in a window that reads: HELP WANTED – APPLY WITHIN. Whether the position is available at IBM, GM, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or a 2-person diner, formation of the relationship between an employer and an employee requires notice that a position is available; from the employer, and an indication of interest; an application, from a prospective employee.

Despite good intentions on the part of most, all methods of recruitment have the potential to be what the text refers to as “an instrument of discrimination.” There are employers whose intent is to discriminate, even pre-employment. This lesson deals with the efforts to link applicants with an available position and the pitfalls that can be encountered using some methods despite no intent to discriminate. Let’s first look at various recruitment methods that can be used to get in touch with applicants.

L03 Recruitment Methods

There are many ways in which employers recruit potential employees. Few of the methods are inherently discriminatory. However, results and a review of why they occur are necessary for that finding. Because of that possibility, employers should use multiple recruitment outlets to lessen the potential exclusionary effects of one method. Let’s look at a few situations to contemplate in this context:

- An advertisement in the town flier for a community that is predominantly Caucasian is not inherently discriminatory. It is likely to result in a recruitment pool that is mostly Caucasian. The recruitment effort should include a method that reaches a more diverse group. If that is not done, reliance on the local town flier could be considered an attempt to exclude minorities, though there may be circumstances that limit an employer’s efforts to attract a diverse pool of applicants.

- An advertisement for RNs, which is unlikely to attract many male applicants as 87.7% are female. Like the previous example, this is not intentionally discriminatory, though it results in a predominantly female recruitment pool. The nature of this trend is not due to discriminatory practices, but rather the nature of a field like nursing, which tends to contain more females to begin with.

- Other professions where there is limited representation for some ethnic groups, such as neurosurgeons and attorneys, and others where one gender is dominant, such as plumbers and engineers.

In this lesson, we will consider statistics and their use in cases alleging discrimination. An excuse that seldom works goes along the lines of “we tried – but they just aren’t out there.” While there are situations where that is true, with others, the problem is a lack of targeted or multiple recruiting methods. There are a variety of recruitment methods available, such as:

- Want Ads and Job Announcements

- Employment Agencies

- Nepotism and Word-of-Mouth Recruiting

- Enlisting Day Labors

Let’s first review want ads and job announcements as a recruitment method used by employers.

L03 Want Ads and Job Announcements

When a job is available, its availability, description and requirements must be made known to prospective applicants. Previously, employers were heavily reliant on newspapers, bulletin boards and trade publications to advertise a position. Increasingly, the Internet is used. Sites such as LinkedIn, ZipRecruiter, and CareerBuilder cannibalize the offerings from other sites and even reverse the process by targeting people who might be qualified or interested.

The federal government uses USAJOBS, while states and municipalities have their own sites. The federal government process of opening a position to a wider recruitment pool than the department in which it exists reinforces the value of using multiple sources. Ads limited to a bulletin board in a plant where most of the workers are of one ethnicity will replicate that search for polar bears in Aruba.

Decades ago, positions in auto plants and at utility companies were made known to only those already working there – which resulted in multiple generations of employees from the same families. That equates to being of the same ethnicity. Such practices are exclusionary.

EEOC Job Posting Requirements

EEOC requirements concerning job postings include:

The U.S. is robust in its protections based on protected classes. Here, want ads must be neutral. Gender-based words such as waitress or seamstress should not be used. A requirement for “young go-getters” would not pass review by the EEOC. “Recent college grad” can be problematical, though some positions target those groups – such as associates at law firms. Further, some “recent college grads” are 40+. Moreover, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act does not permit disparate impact claims by applicants. (Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco, 839 F.3d 958 (11th Cir. 2016), cert. denied, 2017 U.S. LEXIS 4193.)

International Job Posting Practices

In the EU, specifications concerning gender or age preference sometimes appear in ads and are legal. Also, there are mandatory retirement ages in most EU countries. In Hong Kong China, an ad indicating that applicants must be Chinese, female, and 21-28 are acceptable.

The most important thing is that wording of ads must be neutral with no indication of preference based on age, gender, ethnicity, citizenship or national origin.

Next, let’s look at employment agencies as another recruitment method.

L03 Employment Agencies

Employment agencies are covered by antidiscrimination laws and are expressly prohibited from advertising for positions or making referrals in a discriminatory manner. It is naïve to hold that some customers served by employment agencies will not make preferences known or that none will accede to those demands. It is nonetheless illegal per the EEOC:

EEOC enforcement cases against employment agencies have involved code terms for applicants over 40 and refusals to consider African American applicants. Foreign-based companies can limit certain executive positions to their own ethnicities per international trade agreements, but they cannot discriminate when filling other positions.

Aside from those limited exceptions, employment agencies cannot defend against discriminatory practices based on the preferences of their customers. Nor can agencies lawfully serve as filters for applicants based on discriminatory preferences. One discriminatory practice is nepotism, let’s look at that in the next section.

L03 Nepotism and Word-of-Mouth Recruiting

Civil service laws prohibit nepotism, which can be defined as favoring friends, relatives, or associates when hiring. It is discouraged by many large private-sector employers, though not uncommon among smaller employers.

The reasons for the practice are not difficult to comprehend. A position is available; a relative needs a job. Presto! No recruiting costs are incurred and some knowledge about the work ethic of the family is had. The problem is that new hires from the same family as people already working for an employer will be similar – if not identical – as to protected class characteristics. Most often, that has worked against inclusion of African Americans in a workforce.

Word-of-mouth is a process where knowledge about job openings is disseminated by current employees. That system limits the recruitment pool to family and friends. As with nepotism, it excludes members of other protected classes and may be considered a discriminatory form of recruiting.

Unions that require apprentices or new members to be sponsored can have the same outcomes if the membership is not diverse.

Unless the demographics of a region are skewed or diversity is difficult to achieve based on the percentages of applicants qualified for a position, outcomes say it all. Absent those factors, a lack of diversity in a workforce is a function of recruiting methods that warrant review.

Next, let’s look at enlisting day laborers as a final example of a recruitment method.

L03 Enlisting Day Laborers

Day laborers assemble in parking lots near stores like Home Depot and Lowe’s or on street corners. Most big cities have such a place. The services sought are usually reliant on a proverbial strong back.

Undocumented immigrants not authorized to work in the U.S. are often among those gathered. Many of the arrangements work out fine; however, others result in no payment, dangerous work conditions, no breaks, abuse and untreated injuries. Obviously, the system is informal. Many of the workers are reticent to seek redress because of their illegal status. Some have outstanding warrants. Some mistrust government officials or police officers.

The U.S. Constitution prohibits government restrictions on the rights of people to gather, however, municipalities have attempted to limit assemblages of people looking for day work. Is the cure worse than the disease? By eliminating gathering places, the ability to earn a few dollars is also taken. That does not excuse the overarching factors that make day labor an option for some. Until those factors are resolved, it replaces one mean option with another.

An example of a situation in which a city tried to limit assemblies of people is in the upscale city of Danbury, Connecticut. A cruel stunt was put into play, where a police officer offered work to a group of eight day laborers, got them in a van, and took them to the station to be arrested. $400,000 was paid as a result of this event.

Now that we have discussed types of recruitment, in the next section we will look at how to prove discrimination in cases like these and others.

L03 Proving Discrimination in Employment: Statistical Evidence

Many trials involving cases alleging discrimination feature testimony from experts who interpret statistical data reflecting demographics, pools of qualified applicants, and whatever anyone can interpret based on numbers. Experts for plaintiffs and defendants can interpret the same data very differently.

Why the importance of statistical evidence? As previously noted, outcomes say it all. A problem encountered by many who allege discrimination is framing an argument based on outcomes alone. The EEOC is often the proponent in cases alleging discriminatory recruitment practices because those impacted by them are unaware that something was amiss. Most who apply for a position and are not selected move on in their job search. Let’s look at two examples.

EEOC v. Mavis Discount Tire Example

The text includes a case (EEOC v. Mavis Discount Tire, 139 F. Supp. 3d 90 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) where the statistics broke down according to the chart below:

|

Position |

Male |

Female |

|---|---|---|

|

Store Manager |

80 |

0 |

|

Assistant Manager |

287 |

1 |

|

Mechanics |

655 |

0 |

|

Tire Installers |

1677 |

0 |

It is doubtful that many women applied for positions as mechanics (3.6% are women) or tire installers (5.4% are women), which points to how experts for each side will interpret statistics. Representation for women in store management slots is 48.8%. They hold 61% of assistant manager positions. Does combining every position skew the conclusions? What were the demographics concerning the pools of qualified applicants? If the tire shop’s hiring patters reflected the demographics, it should be as follows:

|

Position |

Male |

Female |

|---|---|---|

|

Store Manager |

41 |

39 |

|

Assistant Manager |

102 |

175 |

|

Mechanics |

631 |

24 |

|

Tire Installers |

1597 |

91 |

Apart from those categories, the outcomes in selectees for the positions of store managers and assistants; 367 men and one woman, “says it all.” (EEOC v. Mavis Discount Tire, 139 F. Supp. 3d 90 (S.D.N.Y. 2015.)

It is a basic premise; even axiomatic, that output is a function of input. In other words, a lack of diversity is likely the product of a recruiting effort that produced that outcome. There can be exceptions based on demographics and qualified applicants for a particular position in a relevant labor market. Those situations do not apply to many geographic areas or most jobs that become available.

Other Examples

87.7 % of RNs are women. Women comprise 3.5% of licensed plumbers. A lack of applications from males for RN positions or women for jobs as plumbers would not be, without more, evidence of discriminatory recruiting practices. Those situations are not germane to jobs that call for the general skills many possess. If applicant pools lack diversity, employers should consider adjusting the geographic scope of their recruiting effort, based on what is reasonable or attainable. Where does that begin? Some will drive 50 miles for the right job. Few would consider 500 miles a reasonable commute. As with many things, it depends.

Next, let’s look at affirmative action and the implications it has on the hiring process.

L03 Affirmative Action

The text defines affirmative action as “those actions appropriate to overcome the effects of past or present practices, policies or other barriers to equal employment opportunity.” How affirmative action plans (AAPs) are implemented is a much-embattled undertaking with employment opportunities sometimes dependent on the pipeline provided by colleges and universities.

When percentages, by protected class, of those employed versus those qualified for a position is suspect, an AAP can rectify the matter. When the percentages of qualified applicants, by protected class, are not in line with demographics of a region, the goal should be devised to increase representation – which is where colleges and universities can be instrumental. Let’s look at an example involving physicians in the U.S.

Racial Disparities Among U.S. Physicians

No amount of lawsuits or employer AAPs can remedy the disparities in the population of physicians in the U.S. Gender is not an issue as 61% are female. Other factors are as follows (2020 census):

Races of Physicians in the U.S.

|

Group |

% of Overall Population |

% of Physician Population |

|---|---|---|

|

White |

57.8% |

64.7% |

|

Asian |

7.1% |

18.6% |

|

Hispanic |

18.7% |

9.1% |

|

Black |

12.1% |

4.8% |

Though our focus involves employer-initiated AAPs, the interplay between societal shortcomings and education is part of a solution. As most are aware, the Supreme Court will likely eliminate considerations of race or ethnicity by colleges. The argument is that an advantage to one based on protected class is necessarily a reduction of rights to another based on their protected class.

That would be a “safe” position that would survive whatever the Court does.

AAP Considerations

Basic requirements for employer-initiated AAPs include a formal, written plan devised to improve employment opportunities of groups that, historically, have been victims of discrimination: women, African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asians, Pacific Islanders, disabled persons, and some veterans. Most plans are voluntary undertakings.

Employers that sell goods or services to the federal government worth at least $10,000 must have a non-discrimination clause in their contracts per Executive Order 11246. The Order requires that contractors comply with Title VII. Many states have like requirements.

Where EO 11246 provides goals above those already required is, when there are 50 or more employees and a contract worth at least $50,000, a written affirmative action plan must be developed. The EO also provides enhanced protections for veterans with service-connected disabilities, those who were in combat, and those who were discharged within the last 36 months.

Though most employer-initiated AAPs are voluntary undertakings, courts can order an AAP as a remedy. Some cases end with a settlement – a consent decree – where an employer agrees to develop and implement an AAP. In those cases, “punishing” and employer for past violations is one part of the remedy. In others, an AAP, is devised to prevent future violations and ameliorate damage that has already been done. In the next section, let’s look more into EEOC guidelines for writing and implementing an AAP.

L03 EEOC Guidelines for an AAP

EEOC guidelines state that plans must contain three broad categories: a reasonable self-analysis, a reasonable basis for the AAP, and reasonable actions. Let’s look into the details of these below.

A Reasonable Self-Analysis

A reasonable self-analysis requires that employers evaluate whether its employment practices do, or tend to, exclude, disadvantage, restrict, or result in adverse impact or disparate treatment of previously excluded or protected groups, or leave uncorrected the effects of prior discrimination, and if so, determine why? The analysis should include demographics of a region and by job categories.

A Reasonable Basis for Affirmative Action

A reasonable basis for affirmative action requires underutilization. The latter means when the percentage of women or persons of color in one or more of an employer’s job categories is smaller than the percentage of those with the necessary skills for that type of employment. An example is the prior discussion about percentages, by category and gender, of employees in a tire shop.

- The basis should include a comparison of the demographics of an existing workforce with those who have the requisite skills in a reasonable recruitment area. An example of limitations is the prior discussion about the percentages of physicians by race.

- If the self-analysis establishes that there is underutilization by protected class, actions undertaken must be reasonable. Goals are necessary and must be reasonably attainable through a good faith effort. Preferences based on protected class are not permissible. Nor are quotas.

Reasonable Actions

Blind adherence to quotas would provide the quickest path to correction. It would also risk reverse discrimination. Recommendations generally focus on expanding the recruitment pool to make opportunities known:

- In all communications, clearly state that that the organization is an equal opportunity employer.

- Use recruiting methods and sources likely to reach qualified, diverse applicants.

- Develop relationships with community development and advocacy organizations that can refer qualified, diverse applicants.

- Work with educational and training institutions.

- Establish or maintain facilities in communities with diverse populations.

AAPs must have a projected end and cannot embrace a rapid, overnight effort at correction of a situation that likely developed over decades.

We will study AAPs in greater depth in a subsequent lesson. The focus in Lesson 03 is pre-hire and recruitment activities: how a workforce comes together. Next, let’s look at recruitment and employment of foreign nationals.

L03 Recruiting Foreign Nationals for U.S. Employment

The range of positions filled by foreign nationals is far reaching, ranging from professional sports, to tech, agriculture, seasonal resorts, engineers and health care professionals. Anyone who has worked in a major hospital or medical center is aware of the richness of diversity on medical staffs. Some are second-generation, and some become U.S. citizens. The starters, those who emigrated from other countries, began with a visa.

An example is on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where many seasonal jobs as landscapers and staff at resorts were filled by Jamaicans who were allowed to enter the U.S. and work on H-2 visa (temporary workers). The government implemented requirements that limited the number of visas in various categories. A part of the rationale was a projection that U.S. citizens could fill the void. That did not occur, as here wasn’t a surfeit of people willing to work that hard for the wages paid in view of the cost of living on the Cape. Some businesses were forced to curtail services and hours. Some resorted to recruiting in Puerto Rico, as the residents are U.S. citizens. Similar situations played out in many parts of the country.

The important point to note here is that without immigration and visas, many jobs in the U.S. would go unfilled – from harvesting crops to surgeons in operating rooms. In the next section we will look more into the details of visa programs that enable foreign nationals to work in the U.S.

L03 Visa Programs

Hospitals, engineering firms and tech businesses often have someone in HR who handles visa matters. The process requires vigilance and follow-ups. Recruiting, staffing and employee expectations depend on the process being done right.

Foreign nationals that do not have permanent resident status; a green card, must obtain a visa that will permit them to work in the U.S. The type of work involved, and qualifications define most of the categories. Look at the categories and their specifications in the graphic below.

.png)

Let's discuss the H1-B and H-2A visas in more detail.

There are restrictions to an H1-B visa: it expires after six years, and reentry on another H1-B visa requires absence from the U.S. for at least one year.

H1-B visas are controversial as some maintain that holders displace U.S. workers and drive wages down. As with many controversies, that contention is part truth and fable. Without medical professionals who enter based on H1-B visas, would U.S. hospitals be adequately staffed? If such entries ceased tomorrow, would market forces compel more graduations from medical school and a domestic supply of doctors sufficient to staff U.S. hospitals? With a derivative of increasing minority representation among physicians? Theoretically, yes, but the interim shortage of physicians would be catastrophic.

Employers who hire foreign nationals with H1-B authorization must file a Labor Condition Application with the DOL and attest to the following:

- That H1-B visa holders will be paid at or above the local prevailing wage.

- That benefits equal to those provided to U.S. workers will be provided.

- That H1-B visa holders will not perform work during a strike or lockout.

- That notice of an intent to use the H1-B process will be provided to existing employees and union representatives, if applicable.

- That the employer has not displaced U.S. workers by using the process.

- That no U.S. workers will be laid off during the ninety days before or after filing a petition.

- That an attempt to recruit U.S. workers was conducted and that the qualifications of H1-B hires exceeded those of American applicants.

H-2A visas are issued for temporary work in agriculture or logging, whereas H-2B visas are issued for seasonal work in other industries. Both categories must be supported by evidence that there are too few U.S. workers available, able, and willing to perform the work and that the employment of foreign nationals will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of U.S. workers. H2-A visas require evidence of a contract, reimbursement for travel costs, free housing and minimum rates of pay.

There are at times abuses abound about H2-A and H2-B visas. “Free” housing rarely matches what a consumer would opt for. The EEOC and advocacy groups attempt to monitor and correct shortfalls. Many employers meet their obligations. That some do not shouldn’t shock any readers.

Next, let’s look into labor trafficking and what acts are in place to prevent it.

L03 Labor Trafficking

Labor trafficking is an issue that needs to be understood and looked out for. It is defined as:

Sectors where the practice is most common include:

- agriculture

- domestic help

- traveling sales crews

- the garment industry

- nail salons and the beauty industry

- janitorial services

- the travel and service industries

- fairs and carnivals

- peddling and begging

Some situations also involve sex trafficking, which is more common than labor trafficking in the U.S.

Common elements of the relationships involve recruitment, false promises, indebtedness, isolation, dependence of the employer and abuse. Many workers are undocumented and fearful of reprisal if they seek help, while some enter the U.S. legally through visa programs. Typically, recruitment fees, transportation costs, charges for lodging and interest on the accumulating debt make it impossible for the victim to make headway and escape. Prosecution is difficult as there are many layers of operators across national boundaries. Describing some as fly-by-night operations would be hyperbole in their favor.

Criminal codes prohibit labor and sex trafficking: the Trafficking Victims Protection Act provides criminal penalties and civil remedies. Many organizations attempt to track and prevent human trafficking. Polaris is one. People connected with Polaris relate that good sources for tips about human trafficking are cabbies and hotel workers – those in a position to observe the movement of young people under conditions that are abnormal. Resolution is elusive so long as there are countries where people are without opportunities and willing to accept any type of job, under any condition, to support their families.

The beneficiaries of human trafficking are participants in the private sector, and businesses must play a part. The U.S. is not among the leaders in providing people for exploitation or relying on them for services. The precise scope of the problem is unknown as the hidden nature of the crimes, challenges in identifying victims, and barriers to sharing of information among various stakeholders make it difficult to assess.

Now that we have looked into recruitment options and common issues within hiring, let’s look more into the application process itself.

L03 – The Application Process

More rules and restrictions apply to the application process than one may think. Employers are free to decide whether applications will be accepted or retained when no positions are available. However, there are requirements when an application is submitted for a position that is available and how long they will be accepted and retained. The main concern is to avoid disparate treatment by adhering to a consistent policy that applies to all. No one should be discouraged from applying.

Applications and other records produced in the recruiting process must be kept for at least one year from the date when a hiring decision was made. When a complaint alleging discrimination is filed, records must be retained until there has been a final disposition. Records related to people hired must be retained throughout their employment and for at least one year thereafter. (29 C.F.R. 1602.14 (2017)

What defines an applicant? When does someone staring at a HELP WANTED sign in the window of that two-person diner mentioned earlier go from a passerby to an applicant? The federal government provides a broad definition that includes everything from completing an application to making interest known by other means. That might mean a nod from that person reading the sign at the diner. When someone voluntarily withdraws their application, formally or informally, they are no longer an applicant. (44 F.R. 11998 (March 2, 1978)

Use of the Internet for recruiting and acceptance of applications has prompted employer concerns about retention practices and requirements. A definition applying to general circumstances has yet to be issued. However, specifics apply to federal government contractors with affirmative action plans:

Throughout the application process there is much information shared between the employer and potential candidates. This requires attention paid to be mindful of these interactions and information that can be given as a result. Let’s look into this next.

L03 Protected Classes

Some applicants share a lot of information during applications and interviews, such as mentioning that they are pregnant, have a bad back, are planning to start a family, are married or in the process of a divorce. Employers must ignore the TMI (too much information) factor in making decisions about hiring. Where they must be proactive is being vigilant about preemployment inquiries concerning protected class characteristics. These things to keep in mind include:

- Do not ask about protected class characteristics. Examples include gender, age, race, place of birth, if someone is pregnant or planning to start or add to their family, or disabilities. Inquiries about age can include minimums if necessary to hold the position, as in the case of a bartender. Direct inquiries about citizenship should not be part of an application process. Rather, is the applicant eligible to work in the U.S?

- Do not indirectly inquire about protected class characteristics. Examples include dates of graduation from high school, memberships in organizations or whether someone has filed a worker’s comp claim. A question about graduation from high school is appropriate based on yes or no. Questions about professional and work-related organizations are permissible. Not so nosiness about all affiliations and memberships.

- Requirements, criteria and qualifications should be uniform for all applicants for a position. Examples that do not satisfy that standard include inquiries about marital status or child-care arrangements. Application of different standards based on protected status is disparate treatment or outright discrimination.

- Avoid questions about requirements that have a high probability of disparate impact, which is a disproportionate limitation or denial of an employment opportunity based on a “neutral” requirement or criteria that cannot be justified. An example would be a height requirement of 5’8” for a position. It is “neutral” as it applies to every candidate. It disparately impacts women and members of some ethnic groups. Thus, the employer would be required to provide a business justification for the standard. Inquiries about the nature of a military discharge or arrests are ill-advised. Members of some protected classes experience higher rates of encounters with police and arrests. Questions about convictions are appropriate, though the information must be considered in terms of how long it ago it occurred, the seriousness of the crime and its relatedness to the position.

What can result from inquiries that appear to target protected classes is that it has the potential to make an unsuccessful candidate suspicious of the employer’s motives and can provide direct or circumstantial evidence in support of a finding of discrimination.

L03 Medical Inquiries

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits inquiries about disabilities prior to extending a conditional offer of employment. When a conditional offer is extended, an employer can ask about restrictions or limitations on the ability to perform the required duties. A medical exam can be conducted, if warranted. Then, the consideration entails whether the applicant can perform the duties of the position with reasonable accommodation.

Offers are “conditional” based satisfactory results of a medical exam – excluding genetic tests. When disabilities are at issue, employers cannot discriminate against qualified, disabled persons who can perform the essential functions of the position, with or without reasonable accommodation.

One area where employers can get exposure to possible applicants is on social media. Let’s look at that more in the next section.

L03 Social Media and Recruitment

Accessing social media sites to learn more about an applicant than what is curated in a resume is commonplace with some employers. A reversal of the practice is unlikely.

A problem inherent with accessing social media sites is that information about protected class characteristics – including race, gender, age, pregnancy and religious beliefs – can become known at a time when applications are screened, and applicants are sometimes eliminated. Reasons can become suspect. Recommendations for avoiding that include outsourcing of checking social media sites. Many employers outsource background checks. The process provides a shield between the employer and social media sites where it might learn about protected class characteristics.

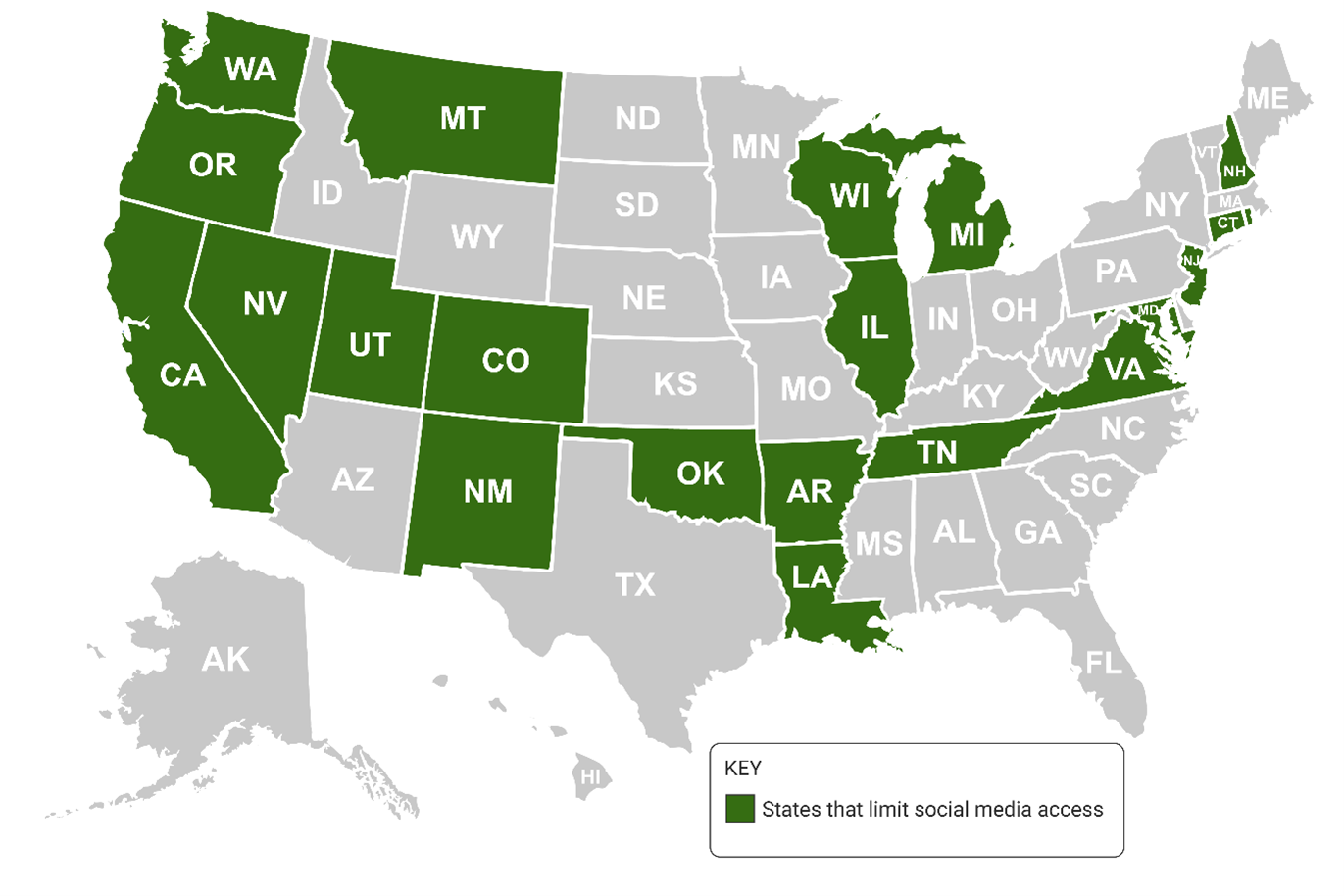

The text indicates that the frequency of employers demanding login access to social media sites is disputed. Whether fact, fiction, or overstated, 21 states shown in the map below have enacted laws limiting employer access to the social media accounts of employees and applicants.

Are the risks worth the information gathered? Information about protected class characteristics can taint the hiring process and provide a basis for allegation of screening based on those characteristics. They can provide a basis for allegations of screening based on protected class characteristics.

Employers should exercise caution, and job applicants should be aware that the Internet is a wide-open, vast place where anything is easily discoverable. Search with discretion and good purpose. Post with an awareness that the Internet is not like the diary of old that can be locked away.

L03 Statements by Employers

Recruitment includes attempts to persuade candidates to accept a job offer: a wooing process. Promises concerning promotions, pay increases or working conditions can provide a basis for legal action involving misrepresentation, breach of contract (implicit, implied or written), and civil fraud.

Fraud requires that a person has been persuaded to accept a position based on misrepresentations such as:

- A false representation of a material fact was made to another person.

- The party making the statement knew that it was false at the time that it was made (or had reckless disregard for the truth).

- The party making the statement intended the other person to rely on the false representation and to act or refrain from acting in a certain way.

- The other person was, in fact, induced or refrain from acting.

- The other person was harmed by reliance on the false misrepresentation.

The bases can include any material representation made during the interview and offer process:

- compensation

- moving expenses

- real estate commissions

- length of assignment or anything that would induce an applicant to accept an offer and in some cases, end their association with another employer.

Similar actions can happen on the part of the employee, let’s look at those in the next section.

L03 Statements by Employees

Embellishments and resumes are symbiotic. Few downplay their qualifications when seeking work. The situation differs when applicants falsify their qualifications or omit material information.

Courts rarely make findings of discrimination when an employer has a consistently enforced policy of disqualifying applicants who fabricate or omit material information and provide notice – usually on the application form.

Employers that discover a falsification or omission subsequent to hiring will generally be able to defend against any claim of discrimination so long as they have a policy requiring applicants to provide complete and truthful information. It is often stated that the consequence of doing so will either be a disqualification or termination, and that the policy is consistently enforced and made known to job candidates. Falsifications and omissions must involve material matters. Trivialities such as slight variations in dates will not provide a defense when actions alleging discrimination have been filed.

Next, let’s look at discriminatory policies and practices.

L03 Facially Discriminatory Policies/Practices: BFOQ Defense

Making an employee decision can be a difficult decision but is one that needs to be taken with an awareness about various concepts and provisions that prevent discrimination and promote equal opportunities. There are two things to consider within the area of employment law that address this: Disparate treatment and bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ). Let’s look more into these below to better understand how discrimination is addressed in the workplace and the legal framework surrounding it.

Disparate Treatment

Making an employment decision based on a protected class characteristic is disparate treatment, which is defined as making employment decisions that are based on protected class characteristics

For example, a Chinese restaurant might insist that its waitstaff be comprised of people whose ethnicity is Chinese because the goal is to provide an authentic dining experience. Also, that is what customers prefer. Seems easy enough and rational. The requirement would be facially discriminatory as only Chinese people would be considered.

Bona Fide Occupational Qualification (BFOQ) and Title VII

The employer’s defense for a facially discriminatory requirement is called a bona fide occupational requirement (BFOQ).

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act define the BFOQ defense as follows:

Regardless of alleged need, the BFOQ defense is not available for policies that discriminate based on race or color.

Title VII states a qualifier of “reasonably necessary to the normal operation” of a particular business. “Reasonably necessary” can be read as a loose, general requirement. Not so when applied by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and courts. A BFOQ must be defended as job-related and consistent with business necessity. Customer preferences that would eliminate some protected classes are not a basis for a BFOQ. Rather, the requirement is that, without the BFOQ, the business would be undermined. Let’s look at how one can recognize BFOQs in the next section.

L03 Grounds for Recognizing BFOQs

Courts have recognized three general grounds for establishing BFOQs: authenticity, public safety, and privacy. These are justifications that can potentially support a business’s need to discriminate based on certain protected characteristics in specific circumstances.

Watch the five minute four second video below that gives more information on disparate impact and BFOQs.

Public safety BFOQs must be defensible because particular protected class characteristics are necessary to protect others. An example is a BFOQ requiring males for certain prison jobs as there was a real potential of violent sex offenders attacking female guards and prison riots ensuing. Protection of others, and not a paternalistic goal of protecting women, was the alleged basis. Similarly, a policy that driver training for truckers must be conducted by trainers of the same gender as trainees based on experience with harassment would not qualify for BFOQ status. In fact, it would serve to prevent hiring female drivers.

Age restrictions and mandatory retirement can be BFOQs if employers establish that the risks posed by older employees are substantial and that more individualized means (i.e., regular medical exams) of identifying risks are not feasible. Examples include commercial airline pilots, whose mandatory retirement age is 65, and FBI Field Agents, who must retire at 57 with extensions to 60 if approved by the Director.

Next, let’s look at hiring criteria and how disparate impact needs to be considered when these are done.

L03 Hiring: Subjective Criteria

Standardized and performance-based interviews sometimes stray from scripts because interviewers are distracted by a response they did not expect and, as all know, some interviewees are unpredictable, interesting or garrulous. A foolproof repellant to subjectivity does not exist. Some positions are filled based on test scores. Even then, is the test entirely objective? Subjective criteria based on interviews includes:

- Appearance

- Does the interviewee seem motivated?

- Will they be team players? Will they fit?

- Is there chemistry?

- Is there a good fit with the goals and ethos of the organization?

- Are they likable?

Subjective criteria rely heavily on intuition, feelings and gut-reactions rather than systemic observations and measurements. Nearly all offers are based on some amount of subjectivity. Most work out. A downside is that they can be viewed as neutral requirements that have discriminatory effects.

Test scores can be challenged based on disparate impact. If the acceptance rate for a position is skewed based on protected class, it would be sufficient to establish a prima facie case alleging disparate impact.

Subjective claims about an interviewee not being a good fit or having a poor attitude can result in claims of discrimination. It is not the role of courts to second-guess employment decisions, but they will delve into whether an employer’s decisions were the true reason for an employment decision. Subjectivity in selections is ubiquitous. Keep in mind that subjective criteria, though commonly relied on, is not the equal of objective standards before a court. Employers are advised to use objective criteria whenever it is feasible.

Next, let’s look more into the specifics of interviews.

L03 Interviews

Few jobs are filled without an interview, whether by phone, Internet or in person. Staffing experts recommend that interviews be structured and consistent because it provides both legal and practical benefits for employers. On the legal side, it provides specific judgments about interview performance based on a consistent method. On the practical side, it benefits the employer with presumably better selections devoid of interviewer bias.

Most interviewers have received advice about not hiring themselves by indulging in the comfortable familiarity of like traits. Or avoiding inherent bias, which is an unconscious favoritism toward or prejudice against people of certain ethnicities or gender. Worse is overt bias, which is bias that is conscious and intentional.

Though judicial reviews of interviews in cases alleging discrimination are also unavoidably subjective, diverse committees, and identical questions with performance-based scoring can make the subjective part of the process more objective.

The goal of most applicants is to wow the interviewer or committee. The goal of the interviewer or committee is to determine if the applicant will be a good fit for the employer and able to perform the duties of the job. Free flowing, give-and-take conversation is tempting. Intuition controls. Many take those routes during interviews. When things work out and no one is unhappy, all is well. When someone contests the outcome, subjective processes are harder to defend. Keep in mind that a complaint about the process does not automatically convert to the unsuccessful applicant being the best candidate as their views are likely more subjective than those of anyone that contributed to the decision.

Most know that specific remarks about protected class characteristics during interviews are either kindly described as lapses in judgment or more aptly depicted as dumb. Stereotypes about women, gays, Blacks or Asians, for example, cannot be written off as being in jest. When remarks are quoted as if it were such, context will be lacking, and it won’t sound like something that should have been said.

L03 Conclusion

Looking back at Lesson 03, we covered the many methods of recruitment, pitfalls and problems to avoid, statistical evidence in discrimination cases, affirmative action plans, the narrow exception of BFOQs, application processes, the complex area of visas, preemployment inquiries, representations by employers during the pre-hiring process, omissions and false information from employees on applications, and subjective versus objective processes during interviews.

We move on to what sometimes transpires when things go wrong after the happy beginning of that first day on the job: discrimination. More about that would be redundant as it warrants mention in the introduction. It is a lively, relevant and interesting topic. See you there!

L03 Case Study Discussion: Overview

This discussion for this week will be based on a case study. Please read the case overview and study the exhibits before participating in the discussion. For the purposes of this case study Downtown refers to an inner-city location. Metroplex refers to the city suburbs.

COMMISSION AGAINST DISCRIMINATION

In Re Julius Watson,

-vs-

Southern County Area Medical.

CASE #26-6723

APPEAL

The Commission Against Discrimination (“CAD”) issued an Order directing South County Area Medical (“SCAM”) to draft an Affirmative Action Plan that will address the statistical shortfalls indicative of discriminatory recruiting and hiring practices addressed herein, which were established based on hearings conducted at Courtroom 106, Downtown, on February 23, 24 and 25, 2022, Administrative Judge Henry Remington (“the AJ”) presiding.

CAD’s customary practice is to hold hearings at the employer’s facility to provide efficiencies pertaining to availability of witnesses and documents. That is especially true when, as here, the Respondent is a healthcare facility. An exception was made in this case as the AJ, having presided over 15 hearings where he found that SCAM engaged in discriminatory practices, fears for his safety in a place he describes as so steeped in exclusionary and discriminatory practices that violations “permeate its walls.”

At issue was a petition filed by the Complainant, Julius Watson, a Black male employed as a laborer. Mr. Watson has been employed by SCAM for fifteen years, all of which he has spent in the labor pool. The demographic composition of the pool was as follows at the time relevant to his complaint:

|

Demographic |

Number in Pool |

|

Male |

21 |

|

Female |

8 |

|

White |

8 |

|

Black |

18 |

|

Hispanic |

3 |

|

Total |

58 |

On November 16, 2021, a selection for the position of leader of the labor pool was announced. Gladys Perez, a Hispanic female, was the successful candidate. Mr. Watson challenged that as discriminatory based on race and gender. Mr. Watson claims that he was more qualified than Ms. Perez based on his fifteen years of experience versus her eight years at the facility.

Testimony of management personnel for SCAM established the following:

- That Ms. Perez had a superior history or performance, as established by evaluations.

- That Ms. Perez has an A.A. with a major in hospital administration whereas Mr. Watson has a GED.

- That Ms. Perez has never been disciplined while employed at SCAM whereas Mr. Watson was counseled for idleness during 2005, 2008, 2011, and 2013 and suspended for periods of three (2007), five (2009) and fifteen (2019) days for various infractions.

AJ Remington held that Ms. Perez was the superior candidate and issued a finding of no discrimination concerning Mr. Watsons complaint, but that a pattern of systemic discrimination was established by statistics he developed because of evidence advanced during the hearing. Principally, he noted as follows:

|

Category |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Labor Pool |

8 |

18 |

3 |

0 |

|

Housekeeping |

12 |

22 |

6 |

0 |

|

Food Service |

16 |

29 |

3 |

0 |

|

Total |

36 |

69 |

12 |

0 |

|

Radiologist |

20 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Psychiatrists |

10 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

Surgeons |

28 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

Dentists |

8 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Internists |

17 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

|

Total |

73 |

5 |

8 |

21 |

Click on the next page to see Exhibits 1-5.

L03 Case Study Discussion: Exhibits 1-5

Below are exhibits 1-5 that were used at the hearing.

Exhibit 1

In his opinion, AJ Remington referred to the first group as Cluster 1 (unskilled workers) and the second as Cluster 2 (skilled workers). He used Downtown demographics for his consideration of staff composition at SCAM:

|

Category |

Downtown |

Metroplex |

State |

USA |

|

White |

10.54 |

70.1 |

78.38 |

71.71 |

|

Black |

82.67 |

22.8 |

14.44 |

12.86 |

|

Asian |

1.12 |

0.2 |

2.58 |

5.30 |

|

Hispanic |

7.07 |

6.2 |

4.69 |

16.91 |

Exhibit 2

Based on statistics for the Metroplex as applied to staff composition at SCAM, AJ Remington determined that there were shortfalls in diversity levels. In the table below numbers are displayed in the following format: 20/8 -12. The first number reflects application of demographics. The second number (after the backslash) represents actual numbers. The third number means + or – from what staff composition should be.

|

Category |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Labor Pool |

20/8 -12 |

07/28 +12 |

2/3 +1 |

0/1 -1 |

|

Housekeeping |

12/28 -16 |

22/9 +13 |

6/4 -2 |

0/1 -1 |

|

Food Service |

28/16 -12 |

29/9 +20 |

3/3 |

0/1 -1 |

Exhibit 3

Based on those calculations, AJ Remington concluded that under and overutilization in unskilled categories was as follows:

|

Category |

Totals |

|

White |

-40 |

|

Black |

+45 |

|

Hispanic |

Even |

|

Asian |

-3 |

Exhibit 4

AJ Remington’s computations for Cluster 2 – using the same method – resulted in the following:

|

Category |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Radiologists |

20/20 |

1/7 -6 |

2/2 |

6/1 +5 |

|

Psychiatrists |

10/11 -1 |

1/4 -3 |

1/1 |

4/0 +4 |

|

Surgeons |

28/20 +8 |

1/8 -7 |

1/2 -1 |

3/1 +2 |

|

Dentists |

8/8 |

1/3 -2 |

1/7 -6 |

2/0 +2 |

|

Internists |

17/12 |

1/6 -5 |

3/2 +1 |

6/1 +5 |

Exhibit 5

Based on those calculations, AJ Remington concluded that representation in medical specialty categories is as follows:

|

Category |

Totals |

|

White |

+19 |

|

Black |

-23 |

|

Hispanic |

-6 |

|

Asian |

+18 |

Click on the next page to see exhibits 6-8.

L03 Case Study Discussion: Exhibits 6-8

Below are exhibits 6-8 that were used at the hearing.

Exhibit 6

After attempts at fashioning a consent decree failed, AJ Remington directed that SCAM develop an affirmative action plan within 90 days with a requirement of quarterly reports concerning progress and to achieve parity in 24 months. CAD agrees with AJ Remington‘s order. SCAM argues that it cherry picks statistics and avoids parameters. It explains that the statistics AJ Remington selected are grossly quantitative and calculated based on sample data for the Metroplex. SCAM urges that the appropriate focus for unskilled positions is the data for Downtown because that is the area from which people can be recruited based on reasonable commutes and the availability of public transportation. Using what it derides as AJ Remington’s “hocus pocus” theory, it asserts that his method would produce the following result for Cluster 1:

|

Category |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Labor Pool |

9/8 -1 |

24/28 +4 |

3/3 |

0/0 |

|

Housekeeping |

12/4 -8 |

22/33 +11 |

3/6 +3 |

0/1 -1 |

|

Food Service |

5/16 +11 |

40/29 -11 |

3/3 |

0/1 -1 |

Exhibit 7

SCAM argues that use of the applicable demographic base results in an indication that variations are within a range that is normal when the recruiting area. Downtown is used rather than AJ Remington’s application of population data for the Metroplex for Cluster 1.

|

Location |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Downtown |

-2 |

+4 |

+3 |

-2 |

|

Metroplex |

-40 |

+45 |

Even |

-3 |

Exhibit 8

SCAM urges that a parameter, the values for the entire U.S. population further refined by the percentages qualified for each specialty, based on race, is correct for positions identified as medical specialties. Its rationale is that recruiting efforts are nationwide, as evidenced by payment of relocation allowances; and that the Metroplex would not produce adequate numbers of applicants. This argument is buttressed by its need to recruit overseas and employ physicians who enter the U.S. with J-1 visas. The percentages of qualified applicants nationwide are as follows:

|

Category |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Radiologists |

65.6% |

4.7% |

8.9% |

18% |

|

Psychiatrists |

64.9% |

5.3% |

9.5% |

18% |

|

Surgeons |

81.7% |

2% |

4.3% |

9.4% |

|

Dentists |

68.3% |

3.6% |

7.7% |

18.7% |

|

Internists |

64.4% |

5% |

9.3% |

18.5% |

Click on the next page to see exhibits 9-10.

L03 Case Study Discussion: Exhibits 9-10

Below are exhibits 9-10 that were used at the hearing.

Exhibit 9

When the parameter SCAM suggests is used as the basis for Cluster 2, AJ Remington’s methodology would result in the following:

|

Category |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Radiologists |

20/19 +1 |

1/1 |

2/3 -1 |

6/5 +1 |

|

Psychiatrists |

10/6 +4 |

1/1 |

1/2 -1 |

4/3 +1 |

|

Surgeons |

28/27 +1 |

1/1 |

1/1 |

3/3 |

|

Dentists |

8/7 +1 |

1/0 +1 |

2/1 +1 |

2/2 |

|

Internists |

17/17 |

1/1 |

3/3 |

6/2 +4 |

Exhibit 10

SCAM argues that use of the correct demographic data base results in an indication that variations are within a range that is normal when the recruiting area, Nationwide and based on the pool of qualified applicants, is used rather than AJ Remington’s application of population data for the Metroplex for Cluster 2:

|

Location |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

|

Nationwide |

+7 |

+1 |

-1 |

+6 |

|

Metroplex |

+19 |

-23 |

-6 |

+18 |

Summary

The difference between CAD’s and SCAM’s positions is based on statistical interpretations and which values should be applied.

CAD holds that the statistical variations establish a need for an affirmative action plan based on a lengthy history of discriminatory recruiting and hiring practices.

SCAM disagrees. It holds that the statistics developed by AJ Remington do not reflect the demographics of reasonable recruiting areas or the percentages of people of any race with the requisite skills for the positions under review. It also notes that even the minor variances shown when its methods are applied are attributable to rounding when figures were above .05 for a position. If that is considered, it emphasizes that Blacks were even more overutilized in the categories of medical specialists than its calculations establish.

Lastly, SCAM argues that AJ Remington’s order does not comply with guidelines concerning AAPs in that there must be a reasonable basis for implementation and realistic expectations as to attainment of goals. SCAM urges that AJ Remington’s decision bears no relationship to the realities of its circumstance. CAD is fully supportive of AJ Remington’s method of development and reliance on relevant statistics.

In accordance with CAD Administrative Regulation #22, the matter is forwarded for a de novo review and consideration by the Supreme Court for HR 501 at Penn State University. It is so ordered.

|

BY: AYN RANDALL for the Commission |

|

L03 Case Study Discussion