LDT581:

Lesson 3: Behaviorism, Cognitivism, and Constructivism

Lesson 3: Behaviorism, Cognitivism, and Constructivism

Introduction

In this lesson, we’ll be reading and reviewing three guiding theories: behaviorist, cognitivist, and constructivist. The behaviorist perspective was historically influential in framing learning during the 1900s and focused on observable behaviors as indicators for learning, as well as the use of rewards to mediate learning. Indeed, behaviorism was the foundation on which many early instructional design models were based, with primary emphasis on measurable outcomes and behaviors. While behaviorist models are not as prevalent in instructional design or technology-based learning environments, it is useful to review the framing of learning within this theory to understand how different theories can impact design, development, and assessment of learning.

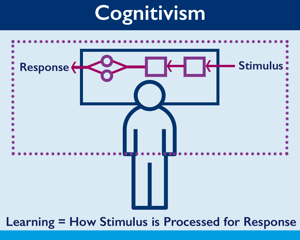

In addition, we will also review cognitivist perspectives on learning, which are closely allied to behaviorist perspectives in assuming an objectivist view of learning, wherein learning could be empirically measured and prescribed. However, cognitivists focus on the mental processes of individuals and attempt to infer the mental processes that result in a specific outcome. Cognitive perspectives are still very prevalent in instructional design, especially for both face-to-face and computer-based training purposes. We will then get a brief overview of constructivism, which will lay some of the groundwork for future traditions that we will explore together.

Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify principles of behaviorism.

- Discuss how learning is presumed to occur within a behaviorist paradigm.

- Discuss cognitivist approaches to learning.

- Identify for what types of learning a cognitive approach might be applied appropriately.

- Appraise when a constructivist approach to learning is being implemented.

- Identify for what types of learning a constructivist approach might be applied appropriately.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Course Schedule.

Remember to engage with your group via Slack by Tuesday evening. Continue the discussion from the last lesson by reviewing and responding to classmates during this lesson. Likewise, you will continue the discussion from this lesson during the next lesson.

Photo Credit: Hemera / Thinkstock

Behaviorism

The chapter on behaviorism, "Radical Behaviorism," by Driscoll, is rather dense, so take some time to read and absorb the information. As you read this chapter, keep the following questions in mind:

- What are the main epistemological and ontological assumptions of behaviorism (revisit these terms from the last chapter)?

- What are the main goals of behaviorist theory?

- Under what conditions might behaviorist theory be best applied?

Behaviorism was based on the assumption that observable behaviors of people were the best indicators of what they were able to do, and by extension, what they might have learned. As noted by Graham (2015), a behaviorist is someone who "demands behavioral evidence for any psychological hypothesis" and, in general, behaviorism can be conceived of as the science of behavior, where behavior can be explained and described without any reference to internal mental states or processes. The self-proclaimed radical behaviorist B. F. Skinner extended his notion of behaviorism to exclude inner physiological processes as well. As we will read, his main argument was that, while inner physiological or mental processes might exist, they were irrelevant for experimental analysis and control of behavior. This approach is well represented by the Figure 2.1 on p. 34, which uses the black box metaphor to represent the individual.

Learning, in the behaviorist perspective, could be conceived of as a set of learned connections between behavioral units. For example, learning to read could be conceived of as a process of learning individual alphabets, and then words, and then sentences to understand language. While not currently popular, behaviorism or behavioral therapy has been used (and continues to be used) for treatment of certain addictions and phobias as well as for animal training. Some forms of instructional design also continue to use behavioral principles such as focus on observable behaviors and use of reinforcements. As you read the chapter, think about contexts in which behaviorism might be suitably applied.

Video Resources

For those of you who prefer visuals, Videos 3.1 and 3.2 offer a quick and lightweight insight into behaviorism. Video 3.1 has a second part that also talks about Skinner's work—remember to click Continue to see that part.

Reference

Graham, G. (2015). Behaviorism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2015 ed.). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2015/entries/behaviorism

Cognitive Perspectives on Learning

As you will read, in a very real sense, behaviorism paved the way for cognitivism to emerge. In the mid-1900s, there was a backlash against behaviorism as it failed to take into account the internal, non-observable mental activity of individuals in explaining behavior. This revolution was spearheaded by the development of computers and the work of Newell and Simon on artificial intelligence, as well as Noam Chomsky’s critique of behaviorism, which was based on his work with language and linguistic competence.

Proponents of cognitive psychology focus on the mental processes that influence behaviors. For example, Neisser (1967) defined cognition as the processes by which "sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used." Cognitive perspectives on learning produced empirical and theoretical refinements on processes such as memory, attention, information processing, and concept formation. In addition, cognitive perspectives viewed the learner as an active participant in the learning process and addressed the importance of identifying what learners know and how they acquired that knowledge in helping them learn further. Learning, in cognitive terms, consists of an active process of acquiring and reorganizing individual cognitive structures. Using the language example and using a cognitive perspective, learning and teaching would be based on the current level of language of the learner and on identifying motivations and active needs of the learner for language learning.

While the largest contrast is in the way the learner is conceived (as a black box in behaviorism; as an active, processing individual in cognitivism), ask yourself in what other ways behaviorism and cognitivism are similar and different.

Reference

Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Constructivism

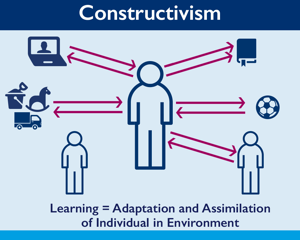

Constructivism has its roots in Jean Piaget’s work with developmental learning in young children, and this theory posits that individuals are active constructors of their own knowledge. Constructivism suggests that individuals accumulate new knowledge based on prior knowledge and experiences and that the process of knowledge construction is guided and shaped by the learner’s physical and cultural environment. While many strands of constructivism have been nominated, they are similar in their positioning of the learner as active and primary in knowledge construction. Importantly, as Sherin will describe, constructivism underscores the incredibly personal nature of learning.

Behaviorism and Cognitivism Wrap Up

Summary

In this lesson, we read about two influential theories of learning that both took different, yet, complementary views of learning. Behaviorism focused purely on observable behaviors and methods to reinforce or fade certain behaviors. Behaviorists tended to focus only on external actions of learners and ignore internal states or processes. In contrast, cognitive perspectives on learning focus on the internal physiological as well as conceptual structures that support behaviors and learning.

Check and Double Check

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 3 Course Schedule.

Looking Ahead

In the next lesson, we’ll be looking at extending cognitive and constructive perspectives on learning and will read about constructivism and constructionism. Both of these theories are still currently popular perspectives in framing learning, although they have evolved and given rise to different forms of designs and environments.

Wrap-Up

Summary

In this lesson, we read about three influential theories of learning that all took different yet complementary views of learning. Behaviorism focused purely on observable behaviors and on methods to reinforce or fade certain behaviors. Behaviorists tended to focus only on external actions of learners and ignore internal states or processes. In contrast, cognitive perspectives on learning focus on the internal physiological as well as conceptual structures that support behaviors and learning. Constructivists believe that learning is deeply connected to what learners “bring to the table,” so to speak. Teachers must be able to have a deep, comprehensive understanding of these experiences in order to help students construct further knowledge.

Check and Double-Check

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Course Schedule.

Looking Ahead

In the next lesson, we shift toward the social dimensions of cognition, particularly in terms of how cognition is very much connected to the specific activities in which it takes place.