MANGT510:

Lesson 2: Project Strategy, Stakeholder Management, and Selection

Lesson 2: Project Strategy, Stakeholder Management, and Selection

Introduction

As we noted in Lesson 1, projects have been referred to as the "stepping stones" of corporate strategy (Cleland, 1998). This idea implies that projects are developed in support of an organization's overall strategic vision. For example, Rubbermaid Corporation is noted for its relentless pursuit of new product development and introduction. In a very real sense, projects are the building blocks of strategies; they put an action-oriented face on the strategic edifice. Some of the examples of how projects operate as strategic building blocks include

- construction of new plants or modernization of facilities to support technical or operating initiatives such as new distribution strategies or decentralized plant operations.

- reengineering projects designed to dramatically redevelop products for greater market acceptance or business processes for greater streamlining and efficiency.

- new product lines to support changes in strategic direction or product portfolio reconfiguration.

- negotiation with supply chain members (including suppliers and distributors) to create new strategic alliances.

- reverse engineering competitors" products and services.

- enterprise IT efforts to enhance cross-organizational communication and improve efficiency in supply chain relationships.

- concurrent engineering to promote cross-functional interaction, streamline new product or service introduction, and improve departmental coordination.

Each of these examples illustrates the underlying theme that projects are the "operational reality" behind strategic vision. In other words, they serve as the building blocks that must be used, one at a time, to create the reality a strategy can only articulate.

Objectives

Think about the following lesson objectives. After completing this lesson, you should be able to:

- Understand the basic elements of corporate strategy and the importance of projects for realizing strategic goals.

- Recognize the various project stakeholders and their role in promoting project success.

- Begin to develop realistic strategies for managing project stakeholders.

- Understand a variety of project selection methods that are used to make screening decisions.

- Understand some of the basic strengths and weaknesses of these selection methods.

2.1 Strategic Management--The Context

Strategic management has been variously defined as the science of formulating, implementing, and evaluating cross-functional decisions that enable an organization to achieve its objectives (David, 2001). Let us consider the relevant components of this definition as they apply to project management. Strategic management, then, consists of the following elements:

- Formulating, implementing, and evaluating

- Cross-functional decisions

- Achieving corporate objectives

- Formulating Strategies

- Developing vision and mission statements

- Conducting an external audit

- Performing an internal audit

- Establishing long-term objectives

- Generating, evaluating, and selecting strategies

- Implementing strategies

- Managerial

- Financial

- Technological

- Functional

- Measuring and evaluating performance

We will spend some time looking at each of these in more detail in the following pages.

2.1.1 Formulating, Implementing, and Evaluating

Projects, being the key ingredients in strategy implementation, play a crucial role in the basic process model of strategic management. A firm devotes significant time and resources to evaluating its business opportunities through developing a corporate vision or mission, assessing internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats, establishing long range objectives, and generating and selecting among various strategic alternatives. All these components relate to the formulation stage of strategy. Within this context, projects serve as the vehicles that enable companies to seize opportunities, capitalize on their strengths, and implement overall corporate objectives. For example, new product development fits neatly into the above framework. New products are developed and commercially introduced as a company's response to business opportunities. It is only through effective project management that firms can efficiently and rapidly respond to such opportunities.

2.1.2 Cross-Functional Decisions

Business strategy is a corporate-wide venture, requiring the commitment and shared resources of all functional areas if global plans are to be realized. The cross-functional nature of such cooperation is a critical feature of project management, bringing together experts from various functional groups into a team of diverse personalities and backgrounds. Project management work is a natural environment in which to operationalize strategic plans.

2.1.3 Achieving Corporate Objectives

Whether the organization is seeking market leadership through low-cost, innovative products, superior quality, or some combination of all these characteristics, projects are the most effective tools to allow such goals to be achieved. As we have noted, a key feature of project management is its ability to allow firms to be simultaneously effective in the external market and internally efficient in their operations; that is, it is a great vehicle for optimizing organizational objectives, whether they incline toward efficiency of production or product or process effectiveness.

2.2 Strategic Management Process Flow Chart

Figure 2.1 shows an example of the strategic management process as represented by a flow chart. Note that, as suggested above, the elements in strategic management can be broadly grouped into three categories: formulation, implementation, and evaluation. Within the formulation stage, a number of discrete steps are required. We will cover these steps in the following pages.

Figure 2.1 Strategic Management Process Flow Chart

David, Fred R., Strategic Management: Concepts, 9th Edition, ©2003.

Electronically reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

2.2.1 Formulating Strategies

Developing Mission and Vision Statements

Vision and mission statements establish a sense of what the organization hopes to accomplish or what they hope to become at some point in the future. A corporate vision serves as a focal, rallying point for members of the organization who may find themselves pulled in multiple directions by competing demands. In the face of multiple expectations and even contradictory efforts, it is highly beneficial to have an ultimate vision that can serve as a "tie breaker" in establishing priorities. A sense of vision is also extremely important for members of the firm to view as a source of motivation and purpose. As the book of Proverbs in the Christian Bible points out: "Where there is no vision, the people perish (Prov. 29:18).

Formulating Strategies--Conducting an External Audit

External audits principally revolve around assessments of opportunities and threats in the external environment. This environment, composed of competitors, customers, regulatory bodies, suppliers, and sources of financial and human resources, provides the firm with the operating arena within which it must successfully compete and thrive. The immediate step necessary to attain success is a clear-headed determination of what opportunities and threats that environment holds for firms struggling to compete in it. As we will see later in this lesson, many aspects of project-based firms require significant external auditing to establish and gain benefit from the management of supply and value chains.

Formulating Strategies--Performing an Internal Audit

The external environment is literally filled with a variety of opportunities waiting to be exploited. A key qualifier in our ability to find these opportunities and gain maximum benefit from them lies in an assessment of the internal strengths and weaknesses of our firm. For example, while we may perceive an opportunity with great commercial promise for the first firm to get their product to market, such rapid innovation may be impossible for our company because we operate with a significant internal weakness whereby we are slow to innovate. In other words, external opportunities and threats must be evaluated through the lens of the operating strengths and weaknesses of the company. Is one of our strengths financial resources? We can then make larger-scale investments than competitors in plant and equipment. Are we innovative and quick to market? Clearly, we need to exploit the opportunities available for "first-mover" products. The internal audit, coupled with an external assessment, forms the basis for what is commonly referred to as SWOT analysis. SWOT analysis derives its name from the interplay of the terms Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats that are all key elements in strategic evaluation.

Formulating Strategies--Establishing Long-Term Objectives

Long-term objectives represent the results expected from pursuing certain strategies (David, 2001). Long-term objectives differ from a firm's vision statement in that they are guided by the overall vision, but also take into consideration the internal strengths and weaknesses of the firm as well as its external opportunities and threats. That is, the vision and operating environment within which a company finds itself shapes long-term objectives. The importance of long-term objectives is that they quantify or make specific, the goals a firm seeks to pursue. For example, one long-term objective might be to improve its project development processes in order to trim an additional 5% from overhead costs associated with new product development. While much has been written on the nature of long-term goals, at their core, such goals are only useful to companies when they are quantifiable, reasonable but challenging, time bound, and in line with the operation of corporate units. One business writer has coined the term SMART goals to identify the key elements necessary for objective setting to be useful (Doran, 1981). Table 2.1 identifies the key features underlying the acronym SMART, as it has been adapted by a Fortune 500 company:

Specific |

The objectives to be sought must be well-defined. |

|---|---|

Measurable |

The objectives must be quantifiable and thus, easily measured. |

Attainable |

The goals must be realistic and generally regarded as within the capacity of the organization to achieve. |

Relevant |

The goals should tie in with the business unit activities or operating departments of the organization. |

Time-Bound |

The objectives should be directly linked to the business reporting cycle, whether it is based on quarterly, bi-annual, or annual assessments. |

Formulating Strategies--Generating, Evaluating, and Selecting Strategies

The final stage of a firm's strategy formulation process consists of generating and selecting among competing strategies in order to pursue their long-term objectives. Strategies are best formulated in conjunction with the previous steps of objective setting and internal and external analysis. Further, a firm can generate many strategies as a starting point for critically evaluating and ultimately selecting those that hold out highest promise of achieving strategic goals. To illustrate, a large, project-based firm developed as a long-term objective, the goal of continuous market penetration into the lucrative oil drilling platform construction business. One key drawback in realizing this objective was the location of their fabrication yard (on the west coast of Finland ), which made their delivery process more expensive than competitors, particularly when competing for contracts in the Gulf of Mexico. While considering a number of alternatives, including moving their operations to Houston, the firm eventually settled on a strategy of partnering with other, U.S.-based firms to take advantage of their geographical proximity while maintaining their own competitive advantage in engineering and product innovation.

2.2.2 Implementing Strategies

Once the organization has agreed on their vision, assessed their internal and external strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, determined long-term objectives, and selected appropriate strategies, the strategy implementation stage becomes key. Strategy implementation is inherently different from formulation because it emphasizes efficient efforts to operationalize corporate strategy. During strategy formulation a firm emphasizes creativity, generating alternatives, critical thinking, and proactivity. However, during the implementation phase, a company is interested not so much in the "what" of objective setting, as the "how" of strategy realization. Therefore, the process of implementing strategies carries with it managerial, financial, technological, and functional considerations. Broadly speaking, we can look at these issues as described in the following pages.

Implementing Strategies--Managerial and Financial

Managerial

Managerial issues include providing the leadership and human resource means and support to fully realize the pending corporate strategy. Managerial concerns are centered on understanding the nature of the challenges to be faced and bringing together all necessary means to see them resolved.

Financial

Financial concerns include the needed resources to financially support the necessary strategies. The use of capital is extremely important to achieving strategy. A simple example: a construction firm seeking to take advantage of a city's continued suburban sprawl will buy up residential land and begin tract house development. Such plans will fail quickly unless the venture is supported by sufficient capital to underwrite the venture.

Implementing Strategies--Technological and Functional

Technological

Technological implementation includes ensuring that the company has the technological means to achieve its strategies. For example, a firm that seeks to streamline its supplier/buyer relationships by upgrading order entry processes must first determine if they have the technically-trained personnel to support such a move, if they have the information systems in place to make it happen, and the hardware and software compatible for such a venture.

Functional

This activity includes making sure that the various functional elements of the organization are supportive of the change in strategy and are willing to operate in an open, systems approach that emphasizes cross-functional cooperation rather than competition and functional "siloing." In the mid-1980s, AT&T was forced to respond to its breakup and the deregulation of long-distance service by developing a new, customer and marketing oriented focus. This shift was difficult for a company that had long been spared the need to actively compete due to its being a monopoly and further, was dominated internally by its R&D function. Top management's strategic decision to shift to a marketing orientation was met with disdain and outright hostility by the traditionally dominant research and development side of the organization. By the end of the 18 months of functional conflict that followed this directive, the vice president for marketing ultimately quit, taking his staff with him. The R&D function "won" their battle against marketing, concentrating on maintaining their power base rather than working together to help make AT&T a competitive player in a new, potentially profitable market.

Implementing Strategies--Final Words

A recurring theme of this section has been to position projects as the tools by which organizations are able to implement strategies. When examining the strategy implementation stage, it is important to recall that projects, then, are the principle vehicle for organizational change, for seizing commercial opportunities, for improving internal operations and efficiency, and so forth. Management, financial, technological, and functional assets are key supporting means by which companies can use projects as a primary means during the strategy implementation phase.

2.2.3 Measuring and Evaluating Performance

The final stage in the strategic management process consists of establishing a review mechanism to assess the performance of strategic decisions, the need to occasionally modify or change them mid-stream, and the means to determine their effectiveness and future steps that may be needed. Note that in Figure 2.2, the evaluation process involves several feedback loops to earlier steps, as a firm recognizes that the need to change its strategy may lead to significant up-stream rethinking. For example, if the evaluation stage of the process demonstrates a misreading of the marketplace for a company's product line, a natural response would be to rethink their external audit in light of this new information. The measurement of strategy is highly important here and reinforces the need to create objectives that are quantifiable, time bound, and specific. It is only to the degree that objectives were correctly developed a priori that a company is able to generate reliable and actionable information downstream.

Project opportunities need to be evaluated against a set of criteria such as that proposed above in order to ensure that we are attempting to develop products and/or processes that enhance our strategic vision rather than distract from it. As we will discover in a future lesson on project selection, the goal of strategic project management is to create a vision for the company's future and then assess project opportunities in terms of whether or not they are able to contribute to that vision.

2.3 Strategic Management Road Map

An alternative model for analyzing the process of strategic management consists of employing a strategic roadmap approach. Roadmaps are processes by which managers are able to navigate through uncharted or poorly defined territory in pursuit of their goal. A strategic roadmap gives a company a sense of direction, a sequencing of important steps, and an ultimate goal toward which it can strive. Figure 2.2 shows a representation of one such roadmap for the strategic management of projects (Cleland, 1996). It identifies 11 stages along a general route for the future of some enterprise and contains several checkpoints along the path to challenge assumptions and reassess the strategic process. The stages in the strategic roadmap include each of the following stages as identified in the animation below. To get information regarding each stage, just click on the road map sign.

| Figure 2.2 Strategic Roadmap To get information regarding each stage, just click on the road map sign. For a printable version of these definitions, click on the figure caption. Cleland, D. L. (1996). Project stakeholder management. In D. L. Cleland and W. R. King (Eds.), Project Management Handbook (2nd Ed.).New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Copyright ©1996. This material is used by permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. |

The strategic roadmap approach to the strategic management of projects is useful because it provides project managers with a framework for both the key drivers in strategic decision making, as well as a process model for navigating through these key components. While Cleland's model is not intended as a "lock step" procedure by which strategic management should occur, it highlights many of the key elements in strategic planning, particularly as they have direct impact on the firm's management of their projects. As with the earlier discussion on alignment among strategic elements, it is important in conducting a strategic roadmap analysis to confirm that each roadmap component is considered not just by itself, but also viewed in relationship to the others. The key lies in creating not just a comprehensive strategic vision, but a consistent one, as well.

2.4 Stakeholder Management

Organizational research and direct experience tells us that organizations and project teams cannot operate in ways that ignore the external effects of their decisions. That is, no manager makes decisions exclusive of consideration of how those decisions will affect external groups (Dill, 1958). One way to understand the relationship of project managers and their projects vis-à-vis the rest of the organization is through employing stakeholder analysis. Stakeholder analysis is a useful tool for demonstrating some of the seemingly irresolvable conflicts that occur through the planned creation and introduction of any new project. An organizational "stakeholder" refers to any individual or group that has an active stake in the activities of an organization. Consequently, when a company makes strategic decisions, they often will have major implications for a number of stakeholder groups; for example, environmental watchdog groups, stockholders, government regulatory bodies, and so forth. Stakeholders can have an impact on and are impacted by organizational actions to varying degrees (Wiener and Brown 1986). In some cases, a corporation must take serious heed of the potential influence that some stakeholder groups are capable of wielding. In other situations, a stakeholder group may have relatively little power to influence a company's activities.

The process of stakeholder analysis is helpful to the degree that it compels firms to acknowledge the potentially wide-ranging effect that their actions can have, both intended and unintended, on various stakeholder groups (Mendelow 1986). For example, the strategic decision to close an unproductive manufacturing facility may make good "business" sense in terms of cost versus benefits that the company derives from the manufacturing site. However, the decision to close the plant has the potential to unleash a torrent of stakeholder complaints in the form of protests from local unions, workers, community leaders in the town affected by the closing, political and legal challenges, environmental concerns, and so forth. Prudent companies will often consider the impact of stakeholder reaction as they weigh the sum total of likely effects from their strategic decisions.

Just as stakeholder analysis is instructive for understanding the impact of major strategic decisions, we are also able to employ project stakeholder analysis for our discussion. Within the project environment, there is also a very real concern for the impact that various project stakeholders can have on the project development process. This relationship is essentially reciprocal in that the project team's activities can also impact the external stakeholder groups (Gaddis 1959). For example, the project's clients, as a group, once committed to a new project's development, have an active stake in that project being completed on time and living up to its performance capability claims. The client stakeholder group can impact project team operations in a number of ways, the most common of which are agitating for faster development, working closely with the team to ease project transfer problems, and influencing top management in the parent organization to continue supporting the project. On the other hand, the project team can reciprocate this support through actions that show their willingness to closely cooperate with the client and smooth transition of the project to its intended user groups.

The key point to bear in mind is that project stakeholder analysis solidifies the fact that in addition to considering all the managerial activities involved in project development, project managers need to be aware of the ways in which attaining the project's goals can impact a host of external stakeholders outside of their authority. Further, project managers must develop an appreciation for the ways in which these stakeholder groups, some of which have considerable power and influence, can affect the viability of their projects. For example, there is an old saying that states, "Never get the accountant mad." The obvious logic behind this dictum is that cost accountants can make the project manager's life easy or very difficult, depending upon the format, frequency, and detail of the reports they request to monitor and control project expenditures.

Stakeholders, while having varying levels of power and influence over the project, nevertheless have the potential to exert a number of significant demands on project managers and their teams. This problem is compounded by the fact that the nature of these various demands quite often places them in direct conflict with each other. That is, in responding to the concerns of one stakeholder, project managers often unwittingly find themselves having offended or angered another stakeholder with an entirely different agenda and set of expectations. The challenge for project managers is to find a way to balance these various demands in order to maintain supportive and constructive relationships with each important stakeholder group.

2.4.1 Identifying Project Stakeholders

In identifying project stakeholders, we need to go beyond the project organization's internal environment to determine which external stakeholder groups can impact our operations and the degree to which they are able to influence the project's implementation. Internal stakeholders are a vital component in any stakeholder analysis and their impact is usually felt in relatively positive ways; that is, while serving as limiting and controlling influences, most internal stakeholders do want to see the project developed successfully. On the other hand, many external stakeholder groups operate in manners that are hostile to project development. For example, consider the case in which a European city is seeking to upgrade its subway system, adding new lines and improving facilities. There is a strong potential for those who are interested in preserving antiquities to actively resist the completion of such a project if they perceive that the tunnel digging could be destroying valuable artifacts. Cleland (1988) refers to these types of external stakeholders as "intervenor" groups and demonstrates that they have the potential to pose a major threat to the successful completion of projects.

Among the set of project stakeholders that project managers must consider are individuals in the following categories.

Internal

- Top management

- Accountant

- Other functional managers

- Project team members

External

- Clients

- Competitors

- Suppliers

- Environmental, political, consumer, and other "intervenor" groups

Let us briefly consider the demands that these stakeholder groups commonly place on project managers. Although we will start with top management, it is also important to note that "top management," as a single entity, may be too simplistic a classification for this stakeholder group. A valid argument could be made that within top management there are obviously differing degrees of enthusiasm for and commitment to the development of a particular project. Likewise, any environmental intervenor groups are likely to be composed of a number of different factions with their own agendas and priorities. In other words, a good deal of conflict and differences of opinion will be discovered within any generalized group. Nevertheless, this approach is useful because it demonstrates the inherent nature of conflict and other pressures arising from project development, as it exists between stakeholder groups, rather than within any group.

Identifying Project Stakeholders--Clients

Our focus in this course rests chiefly with maintaining and enhancing client relationships. In most cases, concerning both external and internal clients, the project deals with an investment. The longer the project implementation, the longer the money invested sits without creating any returns. That is why the clients are concerned with receiving the project as quickly as they can possibly get it from the team. As long as costs are not passed on to the client, they are seldom overly interested in how much expense was involved in the project's development. On the other hand, the project, in a lot of cases, started before the client need was fully defined. Product concept screening and clarification will often be part of the project scope of work. This is the reason why the customers seek the right to make suggestions and request alterations in the project's features and operating characteristics for as long as it is possible without jeopardizing their schedule. The customer feels, with justification, that a project is only as good as it is acceptable and is used by them. As a result, this sets a certain flexibility requirement and requires willingness from the project team to make themselves amenable to specification changes.

The other feature when dealing with client groups lies in the fact that it is erroneous to simply use the term "client" under the assumption that it refers to the entire customer organization. As Figure 2.3 shows, the reality is often far more complex. When an organization is charting a stakeholder management strategy for dealing with a customer, that "customer" must first be more specifically identified. A client firm consists of a number of internal interest groups in many cases with highly different agendas operating. For example, our company can readily identify a number of distinct clients within the customer organization, including the top management team, engineering groups, sales teams, on-site teams, manufacturing or assembly groups, and so forth. Under these circumstances it becomes clear that the process of formulating a stakeholder analysis of a customer organization is a potentially highly complex undertaking.

Figure 2.3 Project Stakeholder Groups

Our challenge is further complicated by the divergent expectations and demands of these various customer stakeholder groups. Preparing a presentation to deal with the customer's engineering staff will require highly technical information and solid specification details. On the other hand, the finance and contractual people are looking for entirely different sorts of information. As a result, formulating stakeholder strategies requires us first to acknowledge the existence of these various client stakeholders, and then a coordinated plan for uncovering and addressing each group's specific concerns to their satisfaction.

Identifying Project Stakeholders--Competitors and Suppliers

Competitors

Competitors can be an important stakeholder element in that they are materially affected by the successful implementation of a project. Likewise, should a rival company bring a new product to market, the project team's parent organization could be forced to alter, delay, or even abandon their project. In assessing competitors as a project stakeholder group, project managers should try to uncover what information is available concerning the status of potential rival projects being developed within competing firms. Further, where possible, the lessons learned by competitors can be an important and useful source of information for a project manager who is initiating a similar project in another company. If a number of severe implementation problems occurred within the first organization's project, that information could offer valuable lessons to other project organizations in terms of what activities or steps to avoid in their own situation.

Suppliers

Suppliers refers to any group that provides the raw materials or other resources that the project team needs in order to complete their project. When projects require a significant supply of externally purchased components, it behooves the project manager to take every step possible to ensure that steady deliveries will continue. In most cases this is a two-way street. First, the project manager has to ensure that suppliers receive timely input information needed to implement their part(s) of the project. Secondly, he has to be able to monitor deliveries, to see that they are met according to the plan. In the ideal case, the supply chain becomes a well-greased machine that automatically both draws the input information from the project team and delivers their products without excessive involvement of the project manager. For example, in large-scale construction projects, project teams must daily face and satisfy an enormous number of supplier demands. The entire discipline of supply chain management is predicated on the ability to streamline our logistics processes through effectively managing the project's supply chain.

Identifying Project Stakeholders--Intervenor Groups

Any environmental, political, social, community-activist, or consumer groups that can have a positive or (more likely) a detrimental effect on the project's development and successful launch are referred to as "intervenor groups" (Cleland 1988). That is, they have the capacity to intervene in the project development and force their concerns to be included in the equation for project implementation. There are some classic examples of intervenor groups curtailing major construction projects, particularly within the nuclear power plant construction industry. As federal, state, and even local regulators decide to involve themselves in these construction projects, they have at their disposal the legal system as a method for tying up or even curtailing projects. Prudent project managers need to make a realistic assessment of the nature of their projects and the likelihood that one intervenor group or another may make an effort to impose their will on the development process. In fact, in some of the better-known project success stories, the construction project manager devoted a great deal of time early in the process to make a stakeholder management assessment of the potential intervenor groups, plotting out strategies for finding the most effective and cost-efficient ways of dealing with them.

Identifying Project Stakeholders--Top Management and Accounting

Top Management

The top management group in most organizations holds a great deal of control over project managers and is in the position to regulate the project managers' freedom of action. Top management is, after all, the body that authorizes the development of the project through giving the initial "go" decision, sanctions additional resource transfers as they are needed by the project team, and supports and protects the project managers and their teams from other organizational pressures. The top management group has, as some of its key concerns, the requirement that the project be timely (the project needs to be out-the-door quickly), cost-efficient (they do not want to pay more for it than they have to), and minimally disruptive to the rest of the functional organization.

Accounting

The accountant's raison d'être in the functional organization is maintaining cost efficiency of the project teams. Accountants support and actively monitor project budgets and, as such, are sometimes perceived as the enemy by project managers. We suggest that this perception, while convenient, is very much wrong-minded. To be able to manage the project, to make the necessary decisions, and to communicate with the customer, the project manager has to stay on the top of the cost of the project in "real time." That is why an efficient cost control and reporting mechanism is needed. Accountants perform an important administrative service for the project manager. Canny project managers will work to make an ally of accountants rather than simply assume that they serve in adversarial capacities.

Identifying Project Stakeholders--Functional Managers and Project Team Members

Functional Managers

The functional managers who occupy line positions within the traditional chain of command represent an important stakeholder group that project managers must acknowledge. Most projects are staffed by individuals who are essentially on loan from their functional departments. In fact, in many cases, project team members may only have part-time appointments to the team, while their functional managers expect 20 hours of work out of them per week in performing their functional responsibilities. This situation serves to create a good deal of confusion, conflict of interest, and seriously divided loyalties among team members, particularly when their only performance evaluation is conducted by the functional manager rather than the project manager. In terms of simple self-survival, team members are likely to maintain closer allegiance to their functional group rather than the project team.

Project managers need to appreciate the power of the organization's functional managers as a stakeholder group. Functional managers, like the accountants, are not usually out to actively torpedo project development. Rather, they have loyalty to their functional roles and they optimize their actions and utilization of their resources in respect to the measurements that are set to them within the traditional organizational hierarchy. Nevertheless, as a formidable stakeholder group, functional managers need to be treated with due consideration by project managers.

Project Team Members

The project team obviously has a tremendous stake in the project's outcome. As noted above, although they may have a divided sense of loyalty between the project and their functional group, in many companies these team members volunteered to serve on the project and are, hopefully, receiving the sorts of challenging work assignments and opportunities for growth that will motivate them to perform effectively. Just as the top management group and the accountants have their priorities, the project team's concerns focus on the need for as much time as the project manager can secure for them. Fast-track schedules mean deadlines: project teams prefer to avoid them. Further, the project team wants the client to "lock in" to project specifications as early as possible. It is much easier for project team members to operate within this environment if they are reasonably sure that the client will not be changing the specifications and asking for new features or additions to the product downstream.

2.4.2 Managing Stakeholders

In acknowledging the importance of stakeholder groups in project management, project managers need to decide to proactively manage the nature of these groups' concerns. Block (1983) offers a useful framework of the political process that has fine application to stakeholder management. In his framework, Block suggests six steps that all prudent project managers should follow:

- Assess the environment

- Identify the goals of the principal actors

- Assess your own capabilities

- Define the problem

- Develop solutions

- Test and refine the solutions

Let's take a moment to discuss each in turn.

Managing Stakeholders--1. Assess the Environment

This dictum implies that prudent project managers must realistically determine what the operating environment is likely to resemble for running the project. Is the project relatively low-key and likely to excite little attention, or is it potentially highly significant? For example, a large computer manufacturer recently undertook to develop a new line of mini computers and storage units that had the potential to lead to great profits or serious losses. In that environment, they took great care to first determine the need for such a product line by going directly to the consumer population and engaging in market research. Likewise, one of the reasons the Ford Taurus was so popular was Ford's willingness to create project teams that included consumers in order to more accurately assess their needs prior to project development.

From a political perspective, one important component of assessing the environment is to ask some central questions:

- Is this project politically sensitive, i.e., will it threaten the organization's status quo or the power balance of any important stakeholder group?

- What steps can our firm begin to take to alleviate these groups concerns?

Prudent project management demands that organizations do not accept, as an article of faith, the belief that all internal stakeholders equally perceive the project as important for the organization, nor should we assume that all external stakeholders hold the same positive or, at worst, benign attitudes to the project's introduction.

Managing Stakeholders--2. Identify the Goals of the Principal Actors

We have already noted that various stakeholder groups have very different concerns regarding a project's implementation, ranging from positive and highly supportive all the way to hostile. As a first step in fashioning a political strategy to defuse negative reaction, a project manager should attempt to paint an accurate portrait of stakeholder concerns: a portrait that is predicated on honest assessment, not self-deception. Fisher and Ury (1981) have noted that the positions various parties adopt is almost invariably based on need. What, then, are the needs of each significant stakeholder group regarding the project? Are their needs in line with those of the organization, or are they more parochial, focusing on protecting their own turf or maintaining the status quo?

Project teams must look for hidden agendas in goal assessment. Frame (1987) has argued that all departments and stakeholder groups exert a set of overt goals that are relevant, but often illusionary. In their haste to satisfy these overt or espoused goals, a common mistake is to accept these goals at face value, without delving into the needs that may drive them or more compelling goals. Consider, for example, a project in a large, project-based manufacturing company to develop a comprehensive project management scheduling system. The project manager in charge of the installation approached each department head and believed that she had secured their willingness to participate in creating a centrally-located scheduling system within the project management division. Problems developed quickly, however, because the IS department, despite their public professions of support, began using every means possible to sabotage the implementation of the system. What was their concern? The belief that placing a computer-generated source of information anywhere beside their own department threatened their position as the sole disseminator of information. In addition to probing the overt goals and concerns of various stakeholders, project managers must look for hidden agendas and other sources of constraint on implementation success.

Managing Project Stakeholders--3. Assess Your Own Capabilities

What do we do well? What (if we are honest) are our potential blind spots? Do I have the political savvy and a sufficiently strong bargaining position to gain support from each of the stakeholder groups? If not, do I have connections to someone who can? Each of these questions is an example of the importance of understanding our own capacities and capabilities. Self-deception is one of the most pernicious causes of career destruction. Whether we deceive ourselves as to our capabilities, needs, or weak points, anything that can serve as a blind spot can also be a source of failure for the project. For example, not everyone has the contacts to upper management that may be necessary for ensuring a steady flow of support and resources. If I realistically determine that political acumen is not my strong suit, the obvious solution is to find someone to help me who has these characteristics. The Scots poet Robert Burns once noted, "Oh wad some Power the giftie gie us/To see oursels as ithers see us!" Each of us needs to seek, as far as we are able, the power of the "giftie" in developing our political skills.

Managing Project Stakeholders--4. Develop Solutions

There are two important points to note about this step. First, developing solutions means precisely that: It means creating an action-plan to address, as much as we are able, the needs of the various stakeholder groups in relation to the other stakeholder groups. This step constitutes the stage in which the project manager, together with the team, seeks to manage the political process. What will work in dealing with top management? In implementing that strategy, what reaction am I likely to elicit from the accountant? The client? The project team? Asking these questions helps the project manager develop solutions that acknowledge the interrelationships of each of the relevant stakeholder groups.

As a second point, remember to do your political homework first, prior to developing solutions (Grundy, 1998). Note the point (stage five) at which this step is introduced. Too often, project managers fall into the trap of attempting to manage a process with only fragmentary or inadequate information. The philosophy of "Ready, Fire, Aim" seems to permeate many of our approaches to stakeholder management. The result of such an attitude is one of perpetual fire-fighting during which the project manager operates much as a pendulum, swinging first from resolving one crisis to having to address another stakeholder related problem. Both pendulums and these project managers share one characteristic: they never reach a goal. The process of putting out one fire creates a new conflagration. Its "solution" sparks yet another blaze.

Managing stakeholders requires project teams to create and maintain multiple strategies that provide project managers with maximum flexibility. The more we are able to refine and use strategies as they are appropriate, rather than relying on one approach regardless of the circumstances, the better and more adeptly we can create and manage constructive relations with project stakeholders.

Managing Stakeholder Groups-- Test and Refine the Solution

Implementing the solutions implies acknowledging that the project manager and team are operating under imperfect information. We assume that stakeholders will react to certain initiatives in predictable ways. Obviously, such assumptions are usually erroneous. In testing and refining solutions, the project manager and team should realize that solution implementation is an iterative process. We make our best guesses, test for stakeholder reactions, and reshape our strategies accordingly. Along the way, many of our preconceived notions about the needs and biases of various stakeholder groups must be refined as well. In some cases, we made accurate assessments. At other times, our suppositions may have been dangerously naive or disingenuous. Nevertheless, this final step in the stakeholder management process forces the project manager to perform a critical self-assessment. It requires the flexibility to make accurate diagnoses and appropriate mid-course corrections.

Managing Stakeholder Groups--Stakeholder Management Cycle

When done well, these six steps are an important method for acknowledging the role that stakeholders play in successful project implementation. They allow project managers to approach "political stakeholder management" much as they would any other form of problem solving, recognizing it as a multivariate problem as various stakeholders interact with the project and with each other. Solutions to political management, once this methodology is used, are often richer, more comprehensive, and more accurate in their assessment of both the project stakeholders and the project manager's own capabilities.

|

Figure

2.4 Project Stakeholder Management Cycle |

An alternative, simplified stakeholder management process consists of planning, organizing, directing, motivating, and controlling the resources necessary to deal with the various internal and external stakeholder groups. Figure 2.4 shows the model as suggested by Cleland (1988) that illustrates the nature of the management process within the framework of stakeholder analysis and management. Cleland notes that these various stakeholder management functions are interlocked and repetitive; that is, this cycle is recurring. As we identify and adapt to stakeholder threats, we develop plans to better manage the challenges they pose. In the process of developing and implementing these plans, we are likely to uncover new stakeholders whose demands must also be considered. Further, as the environment changes or as the project enters a new stage of its life cycle, we may be required to cycle through the stakeholder management model again to verify that our old management strategies are still effective. If, on the other hand, we deem that new circumstances make it necessary to alter those strategies, project managers must work through this stakeholder management model anew to update the relevant information.

2.5 Project Screening and Selection Approaches

Recognizing the importance of corporate strategy also offers the key to understanding the means and motivation behind many choices organizations make when screening projects. Project selection is of critical importance to organizations. When done well, firms can create coherent portfolios of projects that not only support organizational goals and objectives, but also support each other. In other words, a coherent portfolio offers organizations economies of scale, the ability to exploit and most efficiently use scarce resources, and complementarity--the ability for projects to mutually support and benefit each other.

There are a number of useful methods for selecting and screening project opportunities to ensure that the best are selected while marginal ones are rejected. This section will examine some of the more common methods for project selection and screening, identifying the characteristics of these models and give some insight into how best to use them.

2.5.1 Method One: Selection Checklists

The simplest method for project screening and selection consists of developing a list of the various criteria that are important to the project choice decision and "squaring" them with the different project options. For example, if the key issues for selecting a project alternative are cost and speed to market, I would screen each project choice against these two criteria and make the choice that best fits the initial goals. To illustrate, consider the example in Table 2.2 showing a simple checklist model with only four project choices and three decision criteria. Under this checklist approach, after each project is given a performance check (either high, medium, or low), the project accumulating the most positive checks is deemed the optimal choice.

| Project | Criteria | Performance on Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

High |

Medium |

Low |

||

| Project Alpha | Cost | X |

||

| Profit Potential |

X |

|||

| Safety | X |

|||

| Project Beta | Cost | X |

||

| Profit Potential | X |

|||

| Safety | X |

|||

| Project Gamma | Cost | X |

||

| Profit Potential | X |

|||

| Safety | X |

|||

| Project Delta | Cost | X |

||

| Profit Potential | X |

|||

| Safety | X |

|||

Based on this analysis, it is clear that Project Gamma represents the best alternative in terms of maximizing the three criteria of cost, profit potential, and safety. Among the obvious flaws with such a screening model is the nebulous nature of evaluating an item as either high, medium, or low on each of the dimensions. Clearly, terms such as these are inexact and subject to misinterpretation or misunderstanding, depending upon who is doing the evaluating and what assumptions they are making in coming to these conclusions.

Another problem with checklist screening models is that they do not resolve tradeoff questions. For example, is Project Gamma still better than Project Alpha when we consider that safety is the paramount criteria of concern in this circumstance? Likewise, if the criteria all are differentially weighted (i.e., some criteria are clearly more important than others in making the decision), how will that affect the final decision? The quick answer is that it can have a huge impact on our choice and, under the simple model shown above, yield potentially misleading choice information. Let us consider a slightly more complex screening model in which each criterion is assigned a simple weight to distinguish which criteria are more important and which are less.

2.5.2 Method Two: Simple Scoring Model

In the simplified scoring model, each of the criteria is given a weight of importance relative to the other criteria. In this way, the choice becomes more directly based on finding the project that maximizes the decision criteria weighting. Consider the previous example again, but this time, we have assigned a particular importance weight to each of the three criteria as follows:

| Criteria | Importance Weight |

|---|---|

| Safety | 3 |

| Profit Potential | 2 |

| Cost | 1 |

Now, reconsider Table 2.2 in the modified table below (see Table 2.4). With a scoring component added in, the screening choice becomes more complex. The score refers to the qualitative score figured in Table 2.4 (high, medium, or low). High scores are given a value of "3," medium scores are assigned a "2," and low scores receive a value of "1." Hence, in Table 2.4, calculating the weighted score for a project consists of the following steps:

- Assign importance weights to the criteria.

- Assign score values to each criterion in terms of its rating (high = 3, medium = 2, low = 1).

- Multiply the importance weights by the scores to create a weighted score for each criterion.

- Add the criterion-weighted scores to create an overall project score.

| Project | Criteria | Importance Weight |

Score | Weighted Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Alpha | Cost | 1 |

3 |

3 |

| Profit Potential | 2 |

1 |

2 |

|

| Safety | 3 |

2 |

6 |

|

Total Score |

11 |

|||

| Project Beta | Cost | 1 |

2 |

2 |

| Profit Potential | 2 |

2 |

4 |

|

| Safety | 3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Total Score |

15 |

|||

| Project Gamma | Cost | 1 |

3 |

3 |

| Profit Potential | 2 |

3 |

6 |

|

| Safety | 3 |

2 |

6 |

|

Total Score |

15 |

|||

| Project Delta | Cost | 1 |

1 |

1 |

| Profit Potential | 2 |

1 |

2 |

|

| Safety | 3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Total Score |

12 |

Using a scoring model, as shown above, the project selection choice has become more complicated. If criteria weights are assigned as shown, Projects Beta and Gamma tie as the most attractive choices. Either would satisfy our basic decision criteria, thereby yielding the maximum outcome.

2.5.3 Method Three: Profile Models

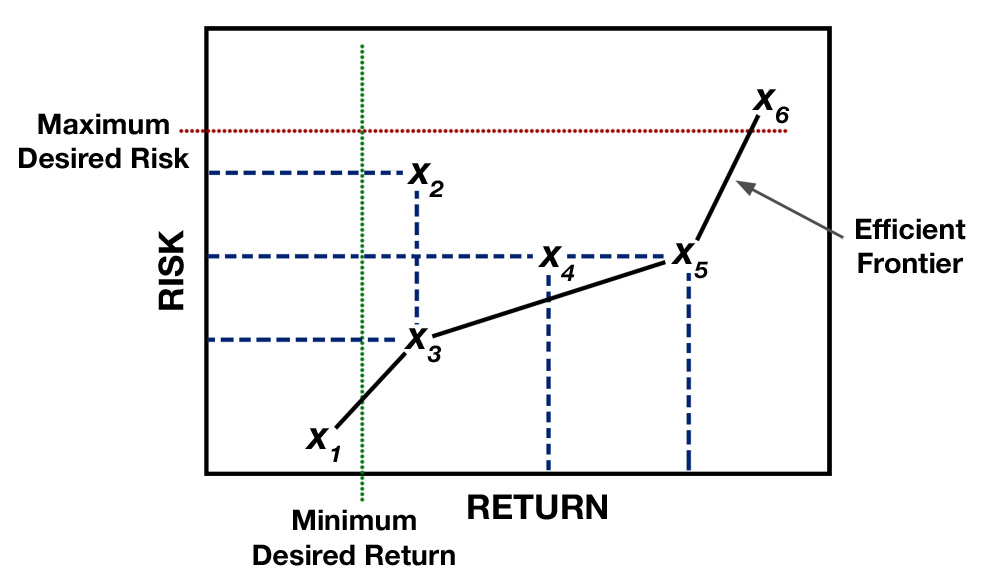

Profile models are another method for visually representing and comparing project alternatives. Specifically, profile models allow the organization to plot risk/return options for various project alternatives, and then select the project that maximizes return while staying within minimum acceptable risk.

Certainly, it should be noted that "risk" is a subjective assessment; that is, it may be difficult to establish an overall agreement on the level of risk associated with various projects. Nevertheless, the risk/return model offers another way for evaluating and screening projects in relation to each other. Consider the example shown in Figure 2.5 below. The four project alternatives we have been using are plotted on a graph with perceived risk on the y-axis and potential return on the x-axis. Because of the cost of capital to our firm, we would specify some minimum desired rate of return, most likely based on our internal rate of return requirements. Likewise, all projects would be assigned some risk factor and plotted relative to the maximum risk our firm is willing to take on. In following this logic, Figure 2.5 shows the graphic representation of each of the four project alternatives on the profile model. Note that these project risk values have been created here simply for illustrative purposes.

We can see that Project Alpha and Project Beta have similar expected rates of return. However, Project Alpha represents a far better selection choice, all else being equal. Why? Because the company can achieve the same rate of return with Project Alpha as it can with Project Beta for appreciably less risk. Likewise, Project Gamma offers a marginally greater return for some additional risk. Finally, Project Delta offers the most potential return, but at the highest level of risk.

The beauty of the profile model is that it offers another alternative for comparing project alternatives, this time in terms of the risk/return tradeoff. It is sometimes difficult to evaluate and compare projects on the basis of scoring models or other qualitative approaches. The profile model, however, gives project managers a chance to map out the potential returns that are available, while taking into consideration the concomitant risk for each choice. Thus, profile models give us another method for eliminating some project alternatives because they offer either too much risk or too little return relative to other choices.

|

| Figure

2.5 Profit Model Evans, D. A., and Souder, W. (1998). Methods of selecting and evaluating projects. In J. K. Pinto (Ed.), Project Management Handbook. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Copyright ©1998. This material is used by permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. |

2.5.4 Method Four: Financial Models

Another important series of models relies on financial analysis to make project-selection decisions. Among the more common types of these models are (1) discounted cash-flow analysis, (2) net present value, and (3) internal rate of return. It is important to note that these are not the only financial methods for assessing project alternatives, but they are among the more popular and hence will be the focus for our discussion.

Discounted Cash Flo

The goal of discounted cash flow (DCF) is the estimate outlays and expected inflows of cash due to the investment in a project. All potential costs of development (most are contained within the project budget) are assessed and projected prior to the decision to initiate the project. They are compared with all expected sources of revenue from the project or the operations of the project. For example, if the project is a new chemical plant, the projected revenue streams are based on expected capacity, production levels, sales volume of the chemicals, and so forth.

The discount rate that is applied to this calculation is based on the firm's cost of capital. That value is weighted across each source of capital that the firm has access to. Typically, for example, most public firms acquire capital through either the debt or equity markets; that is, they either take out loans in the form of long-term debt or they float stock offerings in order to raise money through equity. Weighted cost of capital is calculated as

Kfirm = (wd)(kd)(1 - t) + (we)(ke)

The weighted cost of capital for a firm is the percentage of capital derived from either debt (wd) or equity (we) times the percentage costs of debt and equity (kd and ke respectively). The value t refers to the company's marginal tax rate. Because interest payments are tax deductible, we calculate the cost of debt after taxes. Once a cost of capital has been calculated, it is possible to set up a table projecting costs and revenue streams that are discounted at the current cost of capital for the company. The key is to discover how long it will take the firm to reach break-even point on a new project. Obviously, shorter paybacks are more desirable than longer paybacks with their greater risk. For example, consider Table 2.5:

| Project A | Project B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues | Outlays | Revenues | Outlays | |

| Year 1 | $500,000 | $500,000 | ||

| Year 2 | $50,000 | $75,000 | ||

| Year 3 | $150,000 | $100,000 | ||

| Year 4 | $350,000 | $150,000 | ||

| Year 5 | $600,000 | $150,000 | ||

| Year 6 | $500,000 | $900,000 |

Clearly, Project A is superior in terms of its cash flow to payback. It is projected that this project will require three years to break even, whereas Project B will not break even until some time after year five. All other things being equal, Project A would be the superior choice.

Method Four: Financial Models - Net Present Value

This approach is probably the most popular for financial decision making in project selection. NPV gives the dollar change projects expected in the firm's stock value if a project is undertaken. As a result, a positive NPV indicates that the firm will make money (the value of the company will rise) in undertaking the project.

The simplified formula for NPV is:

NPV(project) = I0 + ∑ |

Ft |

(1 + k + pt)t |

Where:

Ft = the net cash flow for period t

K = the required rate of return

I = initial cash investment (cash outlay at time 0)

Pt = inflation rate during period t

For example, consider a situation in which a firm has the opportunity to invest in a new project. The initial investment cost is $200,000 and the projected net cash inflow per year for the 10-year life of the product is $60,000. Assuming the firm has a required rate of return (hurdle rate) of 15% and anticipated inflation rate is pegged at 3%, we can calculate the NPV for the project as

NPV (project) |

= $200,000 + ∑ $60,000 / (1 + .15 + .03) t |

|

= $69,645 |

Clearly, there would be strong incentive to invest in this project. It has a positive NPV, suggesting that the anticipated revenue generated from the project would more than cover the initial cash outlay required to fund it.

Method Four: Financial Models - Internal Rate of Return

Internal rate of return (IRR) is an alternative method for evaluating the expected income and outlays associated with a new project-investment opportunity. Under this model, the project must meet some internal organizational hurdle rate required of all projects prior to their investment. Without going through the mathematics of the process in detail, the IRR is the discount rate that equates the present values of the revenue and expense streams for a project. Assuming a project has a lifetime of t, the IRR would be the rate that equates:

I0 + |

I1 |

+ |

I2 |

+ ... + |

It |

= R0 + |

R1 |

+ |

R2 |

+ ... + |

Rt |

(1 + k) |

(1 + k)2 |

(1 + k)t |

(1 + k) |

(1 + k)2 |

(1 + k) t |

IRR (represented by the value k) is found through a process of trial and error.

Conclusions: Picking the Selection Approach That Is Right for You

What can we conclude from this discussion of project-selection methods? The first and most important message must relate to the intent we have when deciding how to select a project. Are we consistent and objective with regard to the various alternatives? I have been involved in a consulting and training capacity with a number of firms that expressed severe problems in project selection; in short, they kept picking losers. Why was this the case? One obvious reason that became increasingly clear was that they did not even attempt objectivity in their selection. Projects that were sacred cows or the pet idea of a senior manager were pushed to the head of the line or worse, had their financial assumptions repeatedly "tweaked" until they gave the correct information. In this manner, projects that the majority of the team knew in advance would fail were initiated because they had been massaged to the point that they ostensibly optimized the selection criteria. The key lies in being honest with the selection process. If we continue to operate in a "GIGO" (garbage-in/garbage-out) mode, we are just kidding ourselves.

A second conclusion suggests that some projects require sophisticated financial evidence of their viability. Others may only need to demonstrate an acceptable profile relative to other options. In other words, any of the previously discussed selection methods may be appropriate under certain circumstances. Some authors have pushed strongly for weighted scoring models similar to method two, the simple scoring model described earlier in the lesson (Meredith and Mantel, 2000). They argue that these models offer a more accurate reflection of the strategic goals of a firm without sacrificing long-term effectiveness for short-term financial goals. Further, they suggest that it is important not to exclude these non-financial criteria from the decision modeling process. Perhaps the key lies in creating a selection algorithm that is sufficiently broad to encompass both financial and non-financial considerations. Regardless of the approach a company selects, we do know one thing for sure: making good project choices is a first and vital step in ensuring good project management downstream.

We have now reached the end of Lesson 2. By now, you should have a clearer understanding of strategy choices and methods with regard to selecting projects and managing stakeholders effectively. You should also have completed your reading assignment as specified on your syllabus. At this time, return to your syllabus and complete any activities for this lesson. In the next lesson, we turn to life cycle management of projects.

References

- Block, R. (1983). The Politics of Projects. New York, NY: Yourdon Press.

- Cleland, D. I. (1988). Project stakeholder management. In Cleland, D. I., and King, W. R. (Eds.), Project Management Handbook (2nd Ed.) (pp. 275-301). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Cleland, D. I. (1996). The Strategic Management of Teams. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- Cleland, D. I. (1998). Strategic project management. In Pinto, J. K. (Ed.), Project Management Handbook (pp. 27-40). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- David, F. R. (2001). Strategic Management (8th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Dill, W. R. (1958). Environment as an influence on managerial autonomy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 3, 409-443.

- Doran, G. T. (1981, November). There's a smart way to write management goals and objectives. Management Review, 35-36.

- Fisher, R., and Ury, W. (1981). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

- Frame, J. D. (1987). Managing Projects in Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Gaddis, P. O. (1959). The project manager. Harvard Business Review, 37, 89-97.

- Grundy, T. (1998). Strategy implementation and project management. International Journal of Project Management, 16(1), 43-50.

- Mendelow, A. (1986). Stakeholder analysis for strategic planning and implementation. In King, W. R., and Cleland, D. I. (Eds.), Strategic Planning and Management Handbook (pp. 176-191). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Smith, D. K. and Alexander, R. C. (1988). Fumbling the Future: How Xerox Invented, Then Ignored, the First Personal Computer. New York, NY: MacMillan.

- Weiner, E., and Brown, A. (1986). Stakeholder analysis for effective issues management. Planning Review, 36, 27-31.

Additional Readings

- Biddle, F. M. (1997, October 23). Boeing plans $1.6 billion pretax charge--Output bottlenecks cited. Wall Street Journal, 1.

- Gareis, R., Huemann, M., and Schaden, B. (1998). Best PM practice: Benchmarking of project management processes. In Hauc, A., et. al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 14th World Congress on Project Management (pp. 799-808). Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- Kharbanda, O. P. and Pinto, J. K. (1996). What Made Gertie Gallop? Lessons From Project Failure. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Lee, H. L. and Billington, C. (1993). Material management in decentralized supply chains. Operations Research, 41(5), 835-847.

- Pinto, J. K. and Rouhiainen, P. (2001). Building Customer-Based Project Organizations. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- Pinto, J. K., Rouhiainen, P., and Trailer, J. W. (1998). Customer-based project success: Exploring a key to gaining competitive advantage in project organizations. Project Management, 4(1), 6-11.

- Porter, M. (1985). Competitive Advantage. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Sheridan , J. H. (1999, September 6). Managing the value chain for growth. Industry Week, 50-66.

- Thomas, D. J. and Griffin, P. M. (1996). Coordinated supply chain management. European Journal of Operational Research, 94, 1-15.

- Towill, D. R. (1996). Industrial dynamics modeling of supply chains. Logistics Information Management, 9(4), 43-56.