MANGT515:

Lesson 5: Project Budgeting

Introduction

In the previous lesson, we examined the various problems, concepts and approaches to cost estimation. In this lesson, we will learn about project budgeting--an activity that is inextricably linked with cost estimation. While both cost estimation and budgeting deal with the cost of completing an activity or a work package or a project, estimates precede budgeting. Once the cost estimates, after several revisions, are approved, then it becomes a budget. The various organizational units are then required to complete the work within the constraints imposed by the budget. Essentially, a budget is a plan for allocating resources with an agreed-upon contracted amount of what the work should cost. A budget is much more than a plan; it is also a control mechanism. It serves as the standard against which future expenditures will be monitored for control purposes. Budgets serve a vital role in the process of management, and this particularly true in the management of projects. The budgeting process must relate resource use with the achievement of corporate goals. Otherwise, it has no value as a planning and control mechanism. Timely data collection and reporting are keys to effective budgeting; otherwise, the budgeting process is a wasted exercise as it is not possible to identify and report current problems or to anticipate future problems. The difference between a project budget and a typical fiscal operating budget is that a project covers in the entire duration of the project, whereas the latter covers a time duration of a year. In this lesson, we will examine the various aspects and approaches to project budgeting, including time-phased project budgeting.

Lesson 5 Objectives

After completing this lesson you should be able to:

- Understand the various issues related to project budgeting

- Learn about the top-down and bottom-up approaches to project budgeting

- Learn about the Activity Based Costing method in developing a project budget

- Understand the need and the various aspects of contingency funding in project budgets

- Understand the impact on the project budget when the project is crashed

Road Map

Note: The purpose of the Lesson Road Map is to give you an idea of what will be expected of you for each lesson. You will be directed to specific tasks as you proceed through the lesson. Each activity in the To Do section will be identified as individual (I), team (T), graded (G), or ungraded (U).

To Read:

- Chapter 4: Project Budgeting

- Lesson 5 Commentary

To Do:

There will be an online discussion for this lesson. Please see the Lesson 5 Online Discussion Set-2 for discussion questions (Note: This link will open in a new browser window). (I, G)

In this lesson, you will complete the following assignments which are team-based and graded (T, G). When you have completed these, please submit them to the Lesson 5 Drop Box. (Note: This link will open in a new browser window) Team assignments should be submitted by one member of the team on the team's behalf. Team assignments should be identified by team name as well as the names of all team members.

- Discuss the various aspects of top-down and bottom-up budgeting and the advantages and disadvantages of each of these approaches to developing a project budget.

- What is the need for creating time-phased budgets in projects? What are their major strengths?

- Discuss the three primary reasons for applying contingency funds to projects

- Discuss the impact of project crashing on project budgets

5.1 Issues in Project Budgeting

Developing a project budget not only requires a knowledge of what resources are needed for the project, but also information regarding how many and when these resources will be needed. In addition, it is necessary to know how much the resources will cost. We examined the issue of cost estimation of project resources in the previous lesson and know that it is a daunting task. Unlike traditional organization, the budgeting process for project organization is considerably more complex. The reason it is more complex is that projects are unique, and therefore, project mangers may not have the luxury of accessing and using historical information that is typically available for ongoing and routine activities performed in traditional organizations. While the project manger may rely on budgets and reports from similar projects undertaken in the past, these can only act as rough guides. Consequently, all project budgets are based on estimates of resource usage and their associated costs. The budgeting process gets even more complicated for multi-year projects, as the plans, schedules, associated resource usage, and their costs, which are set early in the project life cycle, may change in future years. This may be due to the availability of newer equipment, more skilled personnel, and the availability of alternate materials for completing project activities.

The accounting systems and practices vary from one organization to the next. Consequently, effective budgeting also requires that the project manager has a thorough understanding of and familiarity with the particular project organization's accounting system and practices. Without this familiarity and understanding, exercising budgetary control over the project is impossible. Yet another budgetary issue that a project manger should be aware of is the way in which resources are actually allocated over the different time periods during the project. The actual usage of resources may be very different from the accounting department assumption about how and when resources are used. For example, assume that $10,000 of a given resource will be used to complete an activity over a five-week period. The actual usage of this resource was $3000 during the first week, none in the second week, $2500 in week 3, $4000 in week 4, and $500 in week 5. If this information about the pattern of resource usage is not included in the plan, the accounting department may distribute the expenditures equally over the 5-week period. While this situation will have no impact on the overall project budget, it certainly has an impact on the timing of the project's cash flow. Finally, the project manager in preparing a project budget should ensure that each and every expenditure is identified and tied to a specific project activity and its associated milestone. The mechanism through which the project manger can accomplish this is through the WBS, which has a unique account number for each element. The account is charged as and when the work is completed. This aspect of project budgeting is absolutely vital if the project manager needs to exercise budgetary control over the project.

5.2 Developing a Project Budget

Developing a project budget involves estimation of costs, subsequent analyses, frequent revisions, and to a certain extent, intuition. Regardless of the type of project budget, the most important caveat is that the budget should be in alignment with and reflect support for both the project and overall corporate goals. Essentially, the project budget is a plan that incorporates the allocation of resources to the various work packages and departments, and a schedule to ensure that the company can is in a position to achieve the project goals. Meaningful budgets are developed through frequent interaction among the concerned parties and require data inputs from a variety of sources. It is worth pointing out that the project budget and project schedule must be developed concurrently, as the budget can provide a clear picture of whether or not project milestones can be achieved.

5.2.1 Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

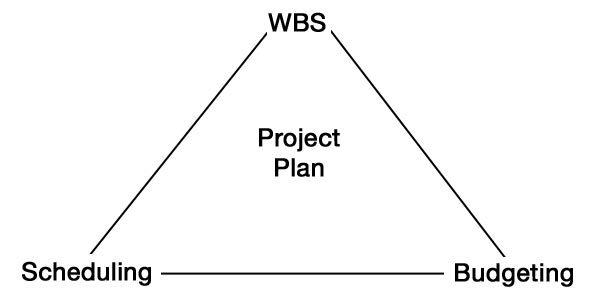

The Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) provides the basis for developing the project budget as various project activities or work packages along with the required resources and their associated cost estimates are identified through the work breakdown structure. As shown in Figure 4.1, the project schedule is created from the WBS and the project budget then allocates the resources needed to support that schedule. Therefore, The WBS, the project schedule and the project budget, together constitute the most important elements of a project plan.

Figure 4.1 – The relationship between WBS, Scheduling, and Budgeting

Source: Pinto, forthcoming. Used with Permission

5.2.2 Issues in Creating a Project Budget*

A number of important issues go into the creation of the project budget, including the process by which the project team and the organization gather data for cost estimates, budget projections, cash flow income and expenses, and so forth. The methods for data gathering and allocation can vary widely across organizations; some project firms rely on the straight, linear allocation of income and expenses, without allowing for time. For example, while it may be common to allocate an amount to cover the cost of producing one work package in the overall project, some firms will allocate that amount as a one-time expense, while others will recognize that the costs accrue over the period of time necessary to complete the work package (say, 3 months). While the method used may not matter when considering the project's overall budget, the difference can have an important impact on cash flow for the project. It is important to recognize the accounting and budgeting system used within a particular organization when preparing the project's budget in order to minimize conflicts with cost control personnel based on misinterpretation of the budget data.

*Please Note: Portions of section 4.2.2 were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

5.3 Approaches to Developing Project Budget

The way in which cost data are collected and interpreted depends on the budgeting approach employed by the project organization. There are two fundamental approaches to developing a project budget: top-down budgeting and bottom-up budgeting. The two approaches use radically different methods for collecting relevant information for developing the project budget and hence can potentially lead to completely different results. Let's take a look at both approaches.

5.3.1 Top-Down Budgeting

The top-down approach seeks to utilize the judgments and experiences of top and senior level managers as well as past data on similar activities in developing the project budget. This budgeting approach assumes that the experiences of the senior management in past projects will enable them to provide guidance to give accurate project cost estimates for future projects. In this approach, the senior level managers first estimate the overall costs of the project as well as the costs of major sub-projects that make up the project. These projections are then handed down to managers in the lower level of the hierarchy to further disaggregate these projections into detailed budget estimates for the specific work packages that comprise the sub-projects. This process is continued at each step down the hierarchy, until the project is broken into and ultimately evaluated on a task-by-task basis at the lowest level of the project organization's hierarchy.

The rationale behind top-down budgeting is that top management may not have the inclination nor the time to estimate the precise cost of each and every element of a project. However, they do indeed have the experience, the knowledge, and the savvy to provide a reasonable aggregate estimate of the overall project's budget. In order to provide more detailed estimates for the various work packages, and subsequently for the individual tasks associated with these work packages, you need to involve personnel in the lower levels of the organization's hierarchy where these work packages and tasks will be accomplished.

Top-Down Budgeting: Advantages

The advantage of top-down budgeting is that top management's estimates of project costs, in aggregate terms, often tend to be quite accurate. Furthermore, these aggregate estimates provide the basis for the disaggregation process of allocating costs to work packages and individual tasks, thereby providing the important feature of budgetary discipline and cost control. Also, because the senior level managers are directly involved in developing the project budget, there is a sense of commitment, ownership and support for creating a viable project budget.

Top-Down Budgeting: Disadvantages*

There are, however, several disadvantages to the top-down approach. First, the lower level managers often feel that their share of the project budget is insufficient for the tasks to be accomplished. In addition, when senior mangers remain steadfast to their budgetary position, the lower level managers feel that they have no choice other than accepting what they perceive as insufficient budgetary allocations to accomplish the work for which they are responsible. Second, as the various departments are competing for a share of the fixed amount of a project budget, the top-down approach can have the net effect of pitting one department against another in the competition for budget money, thereby leading to an adversarial relationship between these departments. Consequently, this process naturally leads to jockeying among different functions as they seek to divide up the budget pie in what has become a zero-sum game--the more budget money engineering receives, the less there is for procurement to use. When functional managers view the budgeting process in this competitive light, there is a strong potential for political behavior, inflated estimates, and other gamesmanship in order to justify inaccurate or deliberately excessive budget requests. In short, top-down budgeting may offer the benefit of relying of top managements' savvy and project management experiences, but it also creates a potentially conflict-laden atmosphere as the lower levels in the organization work to align their specific task budgets with the overall project budget. Clearly, the effectiveness of top-down budgeting depends upon the accuracy and honesty with which it is used. The technique assumes that top management is truly knowledgeable enough to make reasonable cost estimates of the project at hand; if this is, in fact, not the case, the project is immediately saddled with an unrealistic budget that cannot be achieved. Further, some executives use top-down budgeting inappropriately; that is, they may view it as a motivational technique for lower-level managers. Therefore, they will deliberately underestimate the cost of a project in the belief that low estimates on their part will spur cost savings and efficiencies from their subordinates. Either of these approaches is more likely to result in staff demoralization and budget overruns than project success. When used correctly, top-down budgeting can serve as a viable method for cost allocation, but it must be used in accordance with the philosophy that underlies it.

*Please Note: Portions of section 5.3.1 were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

5.3.2 Bottom-Up Budgeting

Bottom-up budgeting pursues a diametrically opposite approach to that pursued by top-down methods. The most important prerequisite for the bottom-up approach is the availability of a detailed WBS that identifies all elements, work packages, tasks, and sub-tasks in the project. By utilizing the framework provided by the WBS, the bottom-up approach begins by constructing individual budgets by assigning both direct and indirect costs associated with labor, materials, and overheads for the most elemental tasks in the WBS. This is accomplished by consulting the personnel who regularly perform these tasks regarding times and budgets for these tasks. Such an approach ensures the most accurate budgets are created. The resulting total costs associated with each activity or task is then aggregated, first to create budgets at the work package level. Subsequently, these work package budgets are then aggregated to create the overall project budget.

In the bottom-up budgeting approach, it is critical that all task elements are identified and included in preparing the project budget. It is, however, considerably more difficult to develop a complete list of all tasks, particularly during the early stages of the project life cycle. In any event, the aggregate budgets developed from the bottom-up are then presented to top management. These top-level managers merge and streamline the various budget proposals and ensure that there is no overlap or double-counting of budgetary resources requested. It is the top management that is ultimately responsible for creating the final master budget for the organization.

Bottom-Up Budgeting: Advantages*

The advantage of bottom-up budgeting, first and foremost, is that it forces the creation of detailed project plans, particularly a detailed work breakdown structure, as an initial step for creating a project budget. Second, the approach facilitates participative management because all personnel, particularly those at the lower levels of the organizational hierarchy, are involved in the project budgeting process. The bottom-up approach assumes that the individuals actually performing the tasks are more likely to have clear understanding of the resource requirements for the tasks than their superiors. Furthermore, involving the lower-level managers and employees in the development of the project budget increases the chances of its acceptance. The involvement of the junior-level managers in the bottom-up approach also provides invaluable training, experience, and knowledge in developing a project budget. Third, bottom-up budgeting facilitates coordination between the project managers and functional department heads, who must take the various resource requests they receive from project managers into consideration as they develop their own budgets. Fourth, bottom-up budgeting, because it emphasizes the unique creation of budgets for each project, allows for top management prioritization among projects competing for resources. If it is determined that there are simply more projects than budget money available, the process of building a budget from the ground up gives top management additional information to use in determining which projects they are willing to support.

*Please Note: Portions of section 5.3.2 were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

Bottom-Up Budgeting: Disadvantages

The major disadvantage of bottom-up budgeting is the reduced role played by top management in the initiation and control of the budgeting process. In other words, the impetus for developing project budgets must now come from lower level managers, while top management's role is limited to analyzing individual budgets presented to them. Such a reduction in top management's role in the budgeting process has the potential to create a significant divide between the strategic thrust and the operational level activities in the organization. It is for this reason that bottom-up budgeting approach is less popular. The budget is the most important control tool for the project organization. Consequently, senior level mangers are reluctant to relinquishing control to inexperienced junior level mangers and personnel. In addition, budgetary game playing by junior levels managers of overstating their budget requirements is yet another disadvantage of bottom-up budgeting. The bottom-up approach can also be a time-consuming process for top management due to the repetitive fine-tuning, adjustments, and delay associated with budget re-submission.

5.4 Activity-Based Costing

Activity-based costing (ABC) is a frequently used method in project budgeting. In activity-based costing, costs are initially assigned to the activities and subsequently to the projects based on each project's use of resources. As project activities are discrete tasks that need to be completed to deliver the project, the basis of Activity-based costing is that projects consume activities and activities consume resources (Maher, 1997).

5.4.1 Steps in Activity-Based Costing

Activity-based costing consists of four steps (Maher, 1997):

-

Begin by identifying the activities that make use of resources and assign costs to them. This step involves using the WBS to break the project down into its elemental activities, or tasks. Based on the resource requirements to complete each identified activity costs is then assigned to that activity.

-

Identify the cost drivers associated with the activity. “Cost drivers” are those elements that cause, or “drive,” an activity's costs. For example, the principle cost driver for many project activities are resources in the form labor assigned to those activities. Similarly material is another project cost driver.

-

Calculate a cost rate per unit of the cost driver. For most projects, human resources are key cost drivers and therefore their values can be stated as cost of labor per hour. Obviously, in addition to labor, project activities will have other cost drivers such as materials.

-

Multiply the cost driver rate per unit by the total number of cost driver units consumed to assign costs to the project that utilized this cost driver. For example, if the cost rate for designer is $50/hour and assuming 100 hours of this designer's time is used on the project, then the cost assigned to the project for this designer is:

$50/hr * 100 hours = $5,000.00

5.4.2 Cost Drivers in Activity-Based Costing

In a typical project, there are several cost drivers relating to both direct project costs and indirect costs, such as overhead expenses. It is imperative that the principle cost drivers are identified early in the project planning phase so that budget projections are based on accurate information regarding the types of expenditures that will be incurred, the cost rates to be charged, and the number of cost driver units to be used. The viability and effectiveness of activity-based costing hinges on the early identification of the principle cost drivers, which in turn will ensure the creation of a meaningful control document.

5.4.3 Sample Project Budget 1*

Table 4.1 illustrates a sample portion of a project budget. In this table, for each project activity both the direct and indirect costs are identified, and budget lines are assigned. This preliminary budget seeks to identify the direct costs and indirect costs such as overhead expenses. It may become necessary to break the overhead expenses to finer levels of detail such as expenses relating to health insurance and so forth. However, breaking a project expenses to this finer level of detail is usually more appropriate when a detailed project budget is developed.

| Budget | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Direct Costs | Overhead | Total Cost |

|

Survey |

4,200 |

800 |

5,000 |

|

Design |

6,900 |

1,100 |

8,000 |

|

Clear Site |

4,500 |

1000 |

5,500 |

|

Foundation |

5,250 |

1250 |

6,500 |

|

Framing |

9,000 |

3,000 |

12,000 |

|

Plumb & Wire |

3,500 |

1,500 |

5,000 |

*Please Note: The activity designations in the sample projects were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

5.4.4 Sample Project Budget 2*

The second sample budget, shown in Table 4.2, takes the total planned expenses identified in Table 4.1 and compares these figures against actual accrued project expenses. This budget can be used for variance reporting through periodic updating to show differences, both positive and negative, between the baseline budget assigned to each activity and the actual cost of completing those tasks. The benefit of such a budget is that it offers a central location for the tabulation of all relevant project cost data and through comparisons between planned and actual budget expenditures. It also allows for the preliminary development of variance reports. The disadvantage of using a static budget document such as the one shown is that it does not reflect the project schedule and the fact that activities are phased in, following the network's sequencing. Hence, as a period-to-period control document, this form of budget may not be as effective a control device for the project as a time-phased budget that allows the project team to evaluate budgets in relation to the schedule baseline.

| Budget | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Planned | Actual | Variance |

|

Survey |

5,000 |

4,250 |

750 |

|

Design |

8,000 |

8,000 |

- 0 - |

|

Clear Site |

5,500 |

3,500 |

1,500 |

|

Foundation |

6,500 |

8,500 |

(2,500) |

|

Framing |

12,000 |

11,250 |

750 |

|

Plumb & Wire |

5,000 |

5,150 |

(150) |

|

Total |

41,000 |

40,650 |

350 |

*Please Note: Activity designations for this sample budget were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

5.5 Program Budgeting

The proliferation of project-based organizations has necessitated the organization of budgets in a manner that more closely conforms to the actual pattern of fiscal responsibility. With the traditional budgeting methods, the budget for a project may be spread over different organizational units. Consequently, it was very difficult establish control and determine the actual amount of major expenditures. The need to rectify this problem led to the creation of program budgets. In program budgeting, income and expenditures are aggregated across projects or programs. This aggregation usually is in addition to aggregation that is done across organizational units. Each project has its own budget that is divided by task and the expected time of completion (Merdith and Mantel, 2003).

5.5.1 Time-Phased Budgets*

In order to achieve effective cost control, time-phasing of project work is absolutely critical.They not only identify budget expenditures for a particular task or work package, but also when these budgetary expenses will be incurred. A sample of a time-phased budget is illustrated in Table 4.3. In this sample, the aggregate budget for a project activity is broken down across various time periods when the various phases of the work on that activity is planned. Thus a time-phased budget will not only show the allocation of the total budget for the various project activities, but also the expected time at which the budgeted monies will be used up. Consequently, the time-phased budget is an excellent project control mechanism, because the project manger can determine during various stages of the project life cycle how much of the budget monies has actually been expended and compare this figure with the planned budgeted amount. The use of the technique of Earned Value Analysis that we is discussed in the Planning and Resource Management course relies greatly on the creation of a time-phased budget. A time-phased budget also enables the project team to compare the schedule baseline with the budget baseline, and thus facilitates the identification of milestones for both schedule performance and project expenditures. In essence, a time-phased budget consolidates the project budget and the project schedule.

|

|

Months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | January | February | March | April | May | Total byActivity |

|

Survey

|

4,000

|

|

|

|

|

4,000

|

|

Design

|

|

5,000

|

3,000

|

|

|

8,000

|

|

Clear Site

|

|

4,000

|

|

1500

|

|

5,500

|

|

Foundation

|

|

|

6,500

|

|

|

6,500

|

|

Framing

|

|

|

2,000

|

8,000

|

2,000

|

12,000

|

|

Plumb & Wire

|

|

|

|

1,000

|

4,000

|

5,000

|

|

Monthly Planned

|

4,000

|

9,000

|

11,500

|

10,500

|

6,000

|

|

|

Cumulative

|

4,000

|

13,000

|

24,500

|

35,000

|

41,000

|

41,000

|

*Please Note: Portions of section 5.5.1 were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

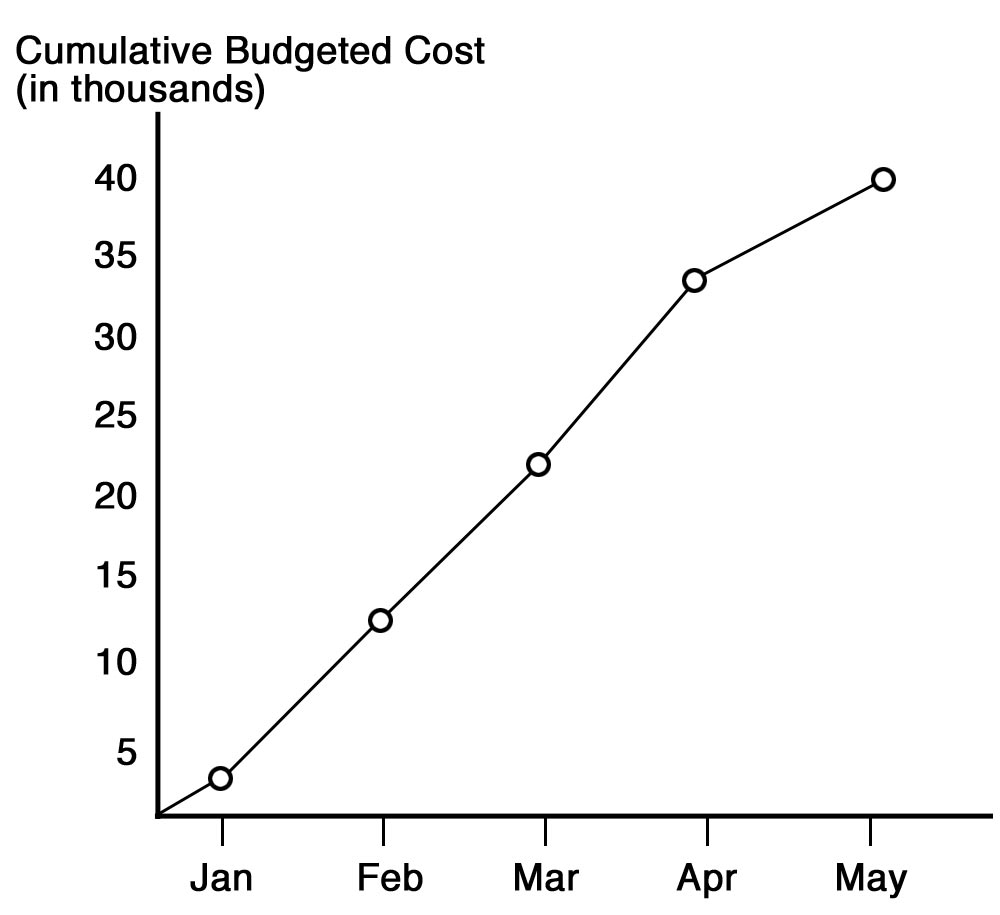

5.5.2 Tracking Chart*

Visually, we can produce a tracking chart that illustrates the expected budget expenditures for this project by plotting the cumulative budgeted cost of the project against the baseline schedule. Figure 4.1 shows a simplified example of the plot and is another method for identifying the project baseline for schedule and budget over the anticipated life of the project.

Figure 5.2 Cumulative Budgeted Cost of the Project

Source: Pinto, forthcoming. Used with Permission

5.6. Issues in Project Development

Developing a project is a complicated and time-consuming process that requires a number of issues be addressed simultaneously. First, we already know that cost estimation is not an easy task, as there are various categories of costs. The project team has to not only determine which categories of costs are relevant and appropriate for the project, but also has to identify the principle cost driver (labor, material, etc.) for each project activity so that a reasonable expense can be charged against that activity. Furthermore, in allocating these resources to the project activity, the project team has to ensure that the task is completed within the time allocated to it by the project schedule. Second, projects are often fraught with risks associated with unexpected and unforeseen events. Hence, the project team has to decide on the amount contingency funds that should be held in reserve which is shown as a separate line item in the project budget. Finally, if the project falls behind schedule, then the project team has to make a decision regarding accelerating (crashing) the project activities which has serious implications for the project budget. In the following sections of this lesson, we will discuss some of these important issues of project budgeting and their ramifications on the overall cost of the project.

5.7 Developing a Project Contingency Budget*

A project contingency budget is created to offset the uncertainty associated with projects. Projects are often plagued by unforeseen events that can cause initial project budgets to be inaccurate and meaningless. For example, suppose a construction project that had budgeted a fixed amount for digging a building's foundation accidentally discovered serious subsidence problems or ground water. The project, facing these serious and unexpected events, would find itself facing serious budgetary problems when they attempted to develop solutions. Budget contingencies symbolize the recognition that project cost estimates are just that: estimates. Even in circumstances in which project unknowns are kept to a minimum, there is simply no such thing as a project developed with the luxury of full knowledge of events. Hence, project teams routinely adopt an extra budgeted amount designed to cover these project uncertainties--the budget contingency. The amount to be earmarked as contingency funds in a project budget varies with the level of uncertainty. The higher the uncertainty associated with the project, the greater the amount allotted as contingency funds.

The purpose of including contingency funds to the budget is to simply ensure that unforeseen events do not delay project completion. They are also intended to offset errors associated with estimation, minor design changes and other omissions. The allocation of contingency funds increases the chances of the work being done within the stipulated amount and thus the confidence attached to it. If that confidence can be raised to a point where the amount seems both realistic and achievable, then its value as a control tool increases significantly.

*Please Note: Portions of section 4.7 were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

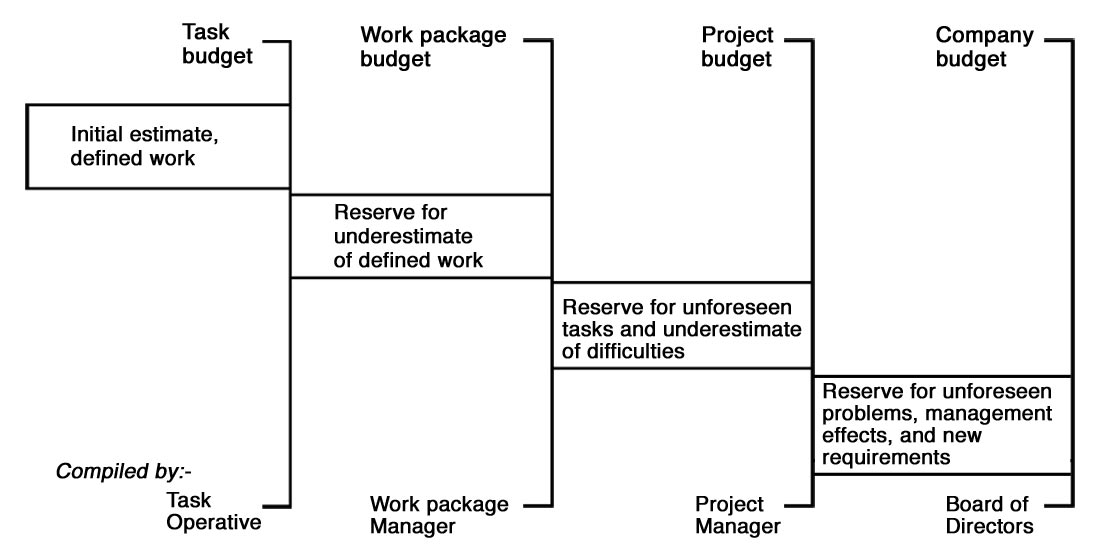

5.7.1 Allocation of Contingency Funds

Contingency money can be added to individual project activities, work packages, or to the project as a whole. Contingency fund allocation is not part of project's budget activity-based costing process. Instead, it is an amount allocated over and above the calculated cost of the project. Some organizations adopt a formal approach to the allocation of contingency funds and include a structured build-up within the project budget as shown in Figure 4.3. Individual task budgets are set at a level that, in the view of the estimator and the manager responsible for the task, is reasonable for the defined work. This will be the budget issued to the personnel required to perform the task. Several minor tasks can come together to form a major task or work package. In addition, by either a rule-of-thumb or a risk assessment method, a contingency is added to the budget to cover underestimates due to unforeseen difficulties in all the minor tasks. The work package manager may, in theory, control the use of contingency to accommodate any overruns.

Figure 5.3 Build up and Allocation of Contingency Funds to Various Budgets

5.7.2 Drawbacks of Contingency Funding*

Contingency funding is a contentious issue for many project organizations. Clearly, project teams support contingency funding as it is a viable tool for effective project cost control. However, their acceptance by project stakeholders, particularly by senior management and clients, is a thorny issue. The clients often feel that they are assuming additional expenses in the form of contingency funds for what was effectively poor control and mismanagement of the original project budget. Furthermore, many clients also feel that the methods used to calculate contingency funds are somewhat arbitrary. For example, it is not uncommon in the building industry to apply a contingency rate of 10 to 15% to any structure prior to architectural design. As a result, a building budgeted for $10 million dollars would be designed, at best, to cost $9 million. The additional million dollars is held in escrow as contingency against unforeseen difficulties during the construction. Consequently, it is not applied to the construction operating budget. The final point of contention with contingency often arises over the decision of where (which project activities) contingency should be applied. Does the contingency fund apply equally across all project work packages, or should it be held in reserve to support only some lesser set of critical activities? Clearly, the project team member whose activities receive additional contingency funding has an advantage over other team members receiving no monetary buffer.

All too often it is concluded by senior management on either the company or customer side that the contingency estimate, itself, must be wrong. Clearly, they reason, the planners and managers have put in excessive contingencies by making pessimistic assumptions that the problems that occurred on the last project will happen again . As most of the estimates represent the judgment of the individuals they can usually be "persuaded" by zealous board members to modify that judgment to something more acceptable. After downward revisions, contingencies are usually the next thing to go; they may be seen as a luxury provision for something that may never happen and if they are included they will be spent whether needed or not. Finally, arbitrary cuts may be applied to bring the budget down to an "acceptable" level. This depressing story will be only too familiar to many project managers.

*Please Note: Portions of section 5.7.2 were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

5.7.3 Advantages of Contingency Funding

In spite of these drawbacks, there are several advantages to the use of contingency funding for projects. They are as follows.

-

There is an explicit recognition that the future is fraught with uncertainty, and there is a potential for occurrences of risk events that can have a negative impact on the project budget. Spending over and above the allocated budgeted amount for the project is more common than underutilizing it. Project delays not only imply that the overall project is not likely to be completed on time, but also trigger a continuous drain on budget money. Contingency funds act as a cushion against both time and money variances in a project.

-

Very few projects are completed within their budgets and most overrun their targets, often by quite large amounts. This does not necessarily imply poor control, but rather the impossibility of anticipating all that will happen in the future, including potential problems that may emerge. Through contingency funding, provision is made in the company plans for these likely, but unexpected, increases in project cost. Application of contingency funding usually signals the onset of problems and the need to request top management for additional time, resource commitment, or budget money. The use of contingency funds in a project is often the first step for gaining approval for budget increases should they become necessary.

-

Use of contingency funds in a project is an early warning signal of a potentially overdrawn budget. When the contingency funds are being applied to the project, there is a clear message is that the normal operating budget for the project has been spent and there is a need for an alternative funding source. Application of contingency funds is a tell-tale sign that the project team is anticipating problems in the not-too-distant future. In the event of such signals, the organization's top management needs to take a serious look at the project, examine the reasons for its budget variance, and begin formulating alternate plans should the contingency funds prove to be insufficient to cover the project overspend.

5.8 Crashing the Project: Budget Effects*

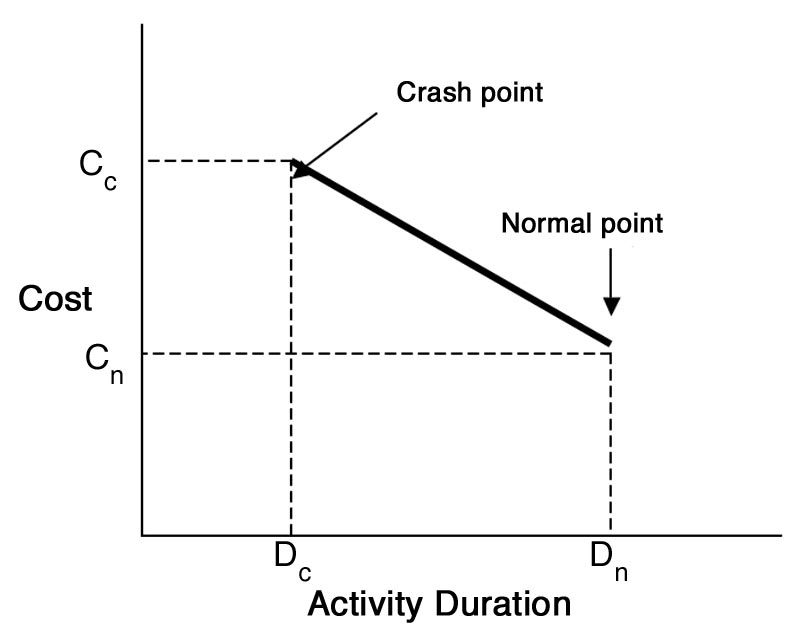

In lesson seven of the Planning and Resource Management course we examine the decision of whether or not to crash a project's activities strictly from the perspective of the schedule. Crashing involves shortening activity duration times by adding resources and incurring additional direct costs. However, crashing project activities has direct impact on the project budget. To illustrate this point, we have reproduced (below, Figure 4.4) the standard time-cost curve discussed in that course. It is clear from this figure that there is an inverse relationship between the cost of crashing and the time saved in accelerating the activity's schedule. Hence, if the cost of crashing an activity is disproportionately high for the time saved, then it is not advisable to crash that activity. On the other hand, if time and schedule issues of the project are critical, as in the case of event project management like the Olympic Games, then it is acceptable to incur the extra cost and the decision to crash the project should be supported.

Figure 5.4 A Standard Time-Cost Tradeoff Curve

Source: Pinto, forthcoming. Used with Permission.

*Please Note: Portions of section 4.8 were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

Crashing Project Activities - Decision Making

Prior to making the decision about crashing project activities, we need to make a clear examination of the project budget in order to determine: 1) which activities are the most likely candidates to be crashed, 2) the additional costs related to the decision to crash these activities, and 3) the impact on the overall budget and a comparison to the time gained from the decision to crash activities.

You will recall from the discussion on crashing the project in the Planning and Resource Management course that in order to shorten the project duration, at least one of the activities to be crashed must be on the critical path. Furthermore, the activity to be crashed first is the one that has lowest marginal cost of crashing compared to the other activities on the critical path. You will also recall that crashing can occur multiple times and the process can eventually lead to multiple critical paths. In such cases, the activities to be crashed are chosen from each of the critical paths that have the lowest marginal cost of crashing. In addition to the direct costs, it is also necessary when crashing the project to account for indirect costs such as overhead expenses and liquidated damages.

*Please Note: Portions of this section were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

5.9 Conclusions*

Along with project cost estimation, project budgeting provides the basis for establishing sound project control and profitability. In order to create an accurate budget for a project, we need to understand the difference between various project costs; direct versus indirect, recurring versus nonrecurring, fixed versus variable, and normal versus expedited. Further, because budgeting is truly only as good as the estimating approaches that were used to first estimate costs, a better understanding of some of the key processes for cost estimation, including recurring problems with estimation can help project managers do a better job of evaluating the types of project costs, assign reasonable values to those costs, and use those figures as the starting point for activity-based budgeting. The budget baseline must work in relation to the project schedule, necessitating the creation of a time-phased budget that recognizes the sequencing of project activities and allows the project team to identify their budget, including assessing its status on an ongoing basis. When properly managed, the project budget, working together with the project's schedule, offer the project team the opportunity to apply maximum control to the project.

You have now reached the end of Lesson 4. This lesson offered insight into some of the key processes, problems, and their resolution in the ongoing effort to create better and more accurate budgets that serve as a baseline for efficient project management. You should also have completed your reading assignment as specified on your syllabus. At this time, return to your syllabus and complete any activities for this lesson. In the next lesson, we will examine change control and configuration management.

*Please Note: Portions of this section were adapted from Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.Used with Permission.

References

- Maher, M. (1997). Cost Accounting: Creating Value for Management. 5th Edition. Chicago, IL: Irwin.

- Merdith and Mantel (2003), Project Management - A Managerial Approach. 5th Edition. New York: John Wiley and Sons, p. 345.

- Pinto, J. K. (forthcoming). Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.