MBADM814:

Course Introduction

Getting Started

Course Syllabus

One of the most important documents you will use throughout the course is the Course Syllabus. Please read this document carefully and contact the instructor if you have any questions or if you need further clarification. The syllabus outlines the readings and activities for each lesson and identifies the due dates for assignments. Keep your syllabus handy; if you have questions throughout the course, this should be your first resource.

Refer to the Course Syllabus at the start of each lesson. Then, read the lesson content and move on to the assigned readings and videos. Be sure to participate in the online discussion(s) throughout the week. Once a lesson discussion is open at the beginning of the week, it will remain open throughout the course. However, to get the most out of the learning experience, you should participate in the discussion during the associated lesson (Monday through Sunday). Finish each lesson by completing the lesson assignments and submitting them for grading by the due date specified in your syllabus.

Stay in Contact

To be successful in this course, we must stay in contact with each other. Given the virtual environment that we are operating in, it is imperative that we foster an ongoing culture of open communication (something that we will talk more about in relation to teams). The instructor will strive to be active and responsive to your questions and concerns as the course unfolds. Conversely, they will count on you to reach out at any time via email, text, Skype, Teams, or Canvas Inbox with any concerns, questions, or comments.

We must work as a team to get the most out of our time together. Thank you in advance for your commitment and hard work.

Get to Know Your Teammates

If you have not completed your OMBA personal introduction yet, as introduced in your Team Performance course, now is the time! The first step in achieving a successful team is getting to know each other, so take a moment this week to share information about yourself with your team in a synchronous session.

Explore your teammates' OMBA personal introductions. In the course navigation menu, go to People and then select the MBADM 814 Project Groups tab. This will direct you to the Canvas Groups area, where you will be able to see which group you are in. Click on each of your classmates' names to access their Canvas profile. Each student's profile will include a link to their OMBA personal introduction.

Keep your personal introduction updated as you move through the OMBA program so that your teammates have your most updated information (and for the purposes of networking).

Organizational Development and Change

“If you don’t like change, you’re going to like irrelevance even less.”

As stated in the course overview, we will integrate change management and leadership communication, given that the two topics are so tightly bound. To understand the interwoven nature of these concepts, it is important to examine how change evolves within organizations and how communication merges with organizational evolution. Let’s begin by understanding the nature of organizations.

It's commonly said that the only constant is change. And, as we are finding, change is a necessary component of everyday life in today's organizations. Doing it better is the mantra for any sensible firm in the 21st century. But how? How do organizations follow this moving target of change while attempting to understand how to do what they do better?

This course is organized according to the foundational framework for organizational change, otherwise known as constant rejuvenation. The course will begin by defining the basic elements of an organization, the system of continuing development within businesses, and the communication strategies necessary to manage organizational change.

It is important to note that organizational development (OD) differs from other planned change efforts, such as technological change or product innovation, in that OD is oriented toward improving the entire system. Keep in mind that organizations do not exist in isolation and therefore must respond to both external and internal forces, which must also be taken into consideration when deciding on the most effective communication strategy. Successful organizations have found a way to exist proactively in a larger environment by managing and communicating planned change. This overview will introduce the foundational components of OD and discuss this field in terms of developing and adapting planned change in an already complex and changing world.

Organizational Development Defined

Organizational development (OD) is an interdisciplinary field spanning business, industrial/organizational psychology, human resources management, sociology, and many other disciplines. There are many definitions of OD, but consider the following by Beer (1980):

Organization development is a system-wide process of data collection, diagnosis, action planning, intervention, and evaluation aimed at (1) enhancing congruence among organizational structure, process, strategy, people, and culture; (2) developing new and creative organizational solutions; and (3) developing the organization’s self-renewing capacity. It occurs through the collaboration of organizational members working with a change agent using behavioral science theory, research, and technology.

This definition highlights the fact that leaders, change agents, and people within the organization directly influence the design of the organization through their actions and decision making. Implicit in design-related activities is the need for change. Therefore, organizational development as a discipline provides a larger backdrop for design and change efforts in organizations as seen in the following definitions.

“Organization design is the making of decisions about the formal organizational arrangements, including the formal structure and the formal processes that make up an organization” (Nadler & Tushman, 1988).

“Organizational design is the deliberate process of configuring structures, processes, reward systems, and people, practices and policies to create an effective organizational capable of achieving the business strategy” (Galbraith, Downey, & Kates, 2002).

You probably noticed some consistent themes when reading these definitions. Anderson (2018) notes the following themes. Click on each for more detail.

Organization design is a set of deliberate decisions

This implies a conscious effort to make choices among competing alternatives and underlies the intentionality of organizational design. As organizations mature, they will naturally evolve and change. Sometimes these changes are well-thought out, like a deliberate change to the business strategy, while other times the change may occur without conscious attention, like the expansion of controls and processes that unintentionally limit flexibility. Sometimes, the external environment forces rapid change on an organization, like the COVID pandemic. Regardless of the change parameters, organizational development implies a conscious management of organizational components to enable an effective response.

Organizational design is a process

Organizations are dynamic and fluid entities that are in a constant state of flux in order to evolve, grow, and adapt to the external environment. Therefore, the process of organizational design is an ongoing activity and change is ever-present. Every organization decision has design and change implications, whether a company decides to enter a new market, discontinue a product line, enhance or reduce services, or grow through an acquisition or merger. “To some extent, managers are making design decisions all the time. Every time a specific job is assigned, a procedure created, a method altered, or a job moved, the organizational design is being tinkered with” (Nadler & Tushman, 1988).

Organizational design assumes a systems approach to organization

Organizations are open systems that interact with their environment in dynamic ways by exchanging information, materials, and energy through inputs, transformational processes, and outputs. As the environment changes, the organization must change and adapt in response. Thus, open systems thinking is the process of considering how people, processes, structures, and policies all exist in an interconnected web of relationships. A systems perspective assumes the following (Deszca, Ingols, & Cawsey, 2019):

- A system is the product of interrelated and interdependent parts and is a complex set of interrelationships that cannot be explained by linear cause-effect relationships

- A system seeks equilibrium and when it’s in equilibrium, it will only change if some energy is applied

- Things that occur within and/or to open systems (e.g., issues, events, forces) should not be viewed in isolation, but rather should be seen as interconnected, interdependent components of a complex system.

These assumptions reinforce the premise that changes in one part of the organization will inevitably affect operations in another. This is an important reminder for change practitioners as they make daily decisions in organizations and they should avoid quick fixes to the latest management problem. “The causes of a problem may be complex, may actually lie in some remote part of the system, or may lie in the distant past. What appears to be cause and effect may actually be coincidental symptoms” (Carnall, 2007).

Finally, organizations have a history of balancing and refining forces over time. In other words, reinforcing those activities that work and discarding those that don’t in the eternal search of efficiency. Accordingly, organizations achieve a certain equilibrium or balance over time and any proposed changes that disrupt this balance will almost certainly encounter resistance. We will learn more about this idea of equilibrium in future modules as we discuss congruence, alignment, fit, and culture.

Want to Learn More?

Organizational design is based on the organization’s strategy

Strategic choices that a company makes will affect all aspects of the system and drives the accomplishment of goals and objectives. Form follows function in that the business strategy shapes organizational design decisions. Therefore, successful design decisions require a deep understanding of the context in which the organization competes, the business model, its value proposition, and the capabilities it needs to be effective. Different strategies require different designs, so every company is different in how it is organized. For example, an organization in the technology sector requires a design that embraces constant innovation and new products where a low-cost manufacturer requires a design that enables an efficient and stable production process.

So when we talk about organizational change, we refer to the planned alterations of organizational components to improve efficiency and effectiveness.

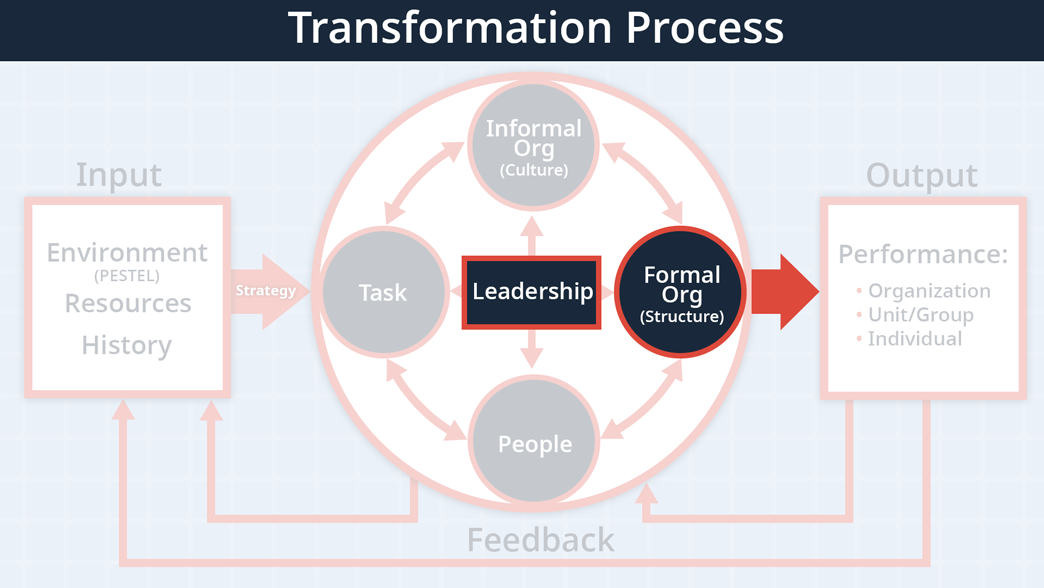

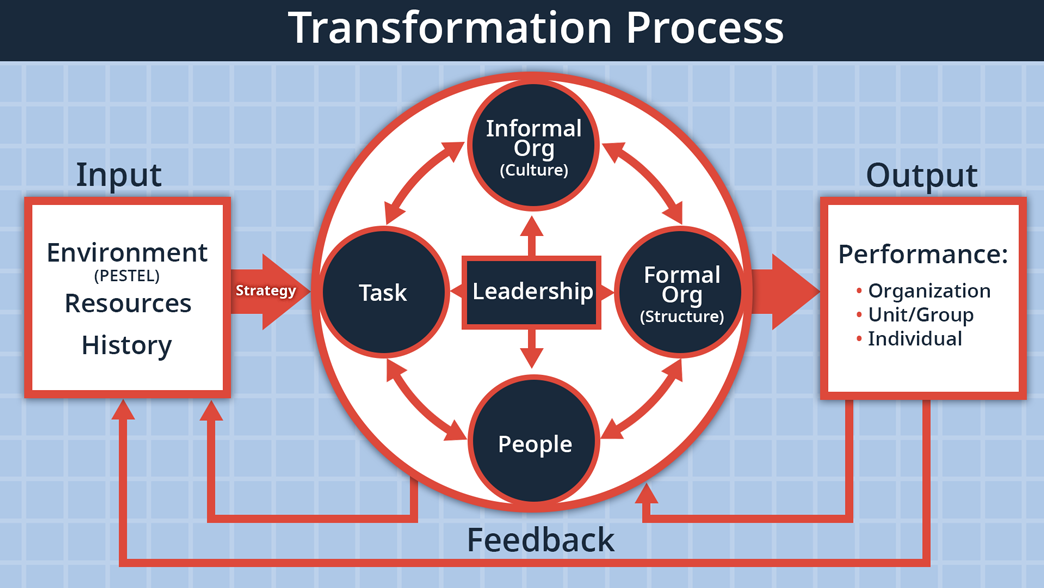

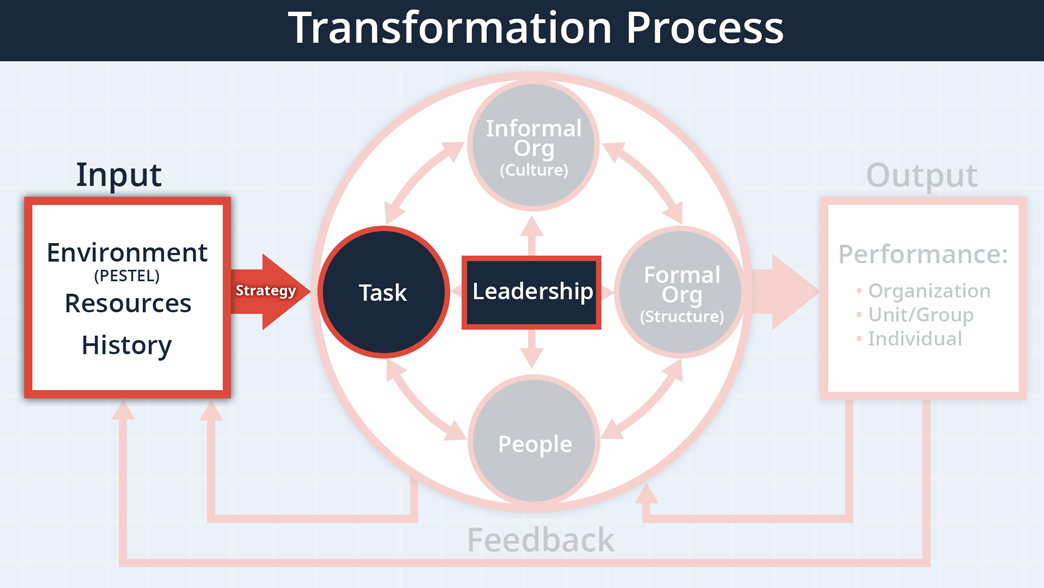

Conceptualizing the Course Using the Congruence Model

The Congruence Model by David Nadler and Michael Tushman (1980) encapsulates the idea of organizations as an open system. It provides a conceptual blueprint of an organization that captures its component parts, and how they fit together. The model asks us to examine the inputs such as environment, resources, history and strategy that drive decision-making, processes, people, and technology within the organization, which ultimately lead to outputs at the individual, unit, and system level. The outputs determine the performance and effectiveness of the organization based on its products and services.

As a comprehensive model, the authors focus on the fit between the components and the external environment. The more congruence there is among the internal components and the more aligned they are with the environmental realities and strategy of the organization, then the better the organization’s performance will be. They argue that strategy needs to flow from an accurate assessment of the environment to include the ability to respond to or take advantage of changes in the environment. In turn, the strategy needs to fit the organizational capabilities and competencies, or the organization needs to develop new capabilities and competencies that are aligned with the strategy. The congruence between these components reflects the effectiveness of the organization. Inside the organization, the components (task, people, structure, and culture) must also fit each other.

For example, an organization might opt to change its structure to better empower its employees and spark greater coordination among its units. But if it fails to adjust the decision-making authority and rewards system to reinforce these new behaviors, or if the culture of the organization is one of mistrust, this lack of fit could easily derail the change effort. See Figure 1.1 (Congruence model) for an adapted version of the model.

I have adapted Nadler and Tushman’s original model to reflect the importance of leadership as the central feature in the model. Nadler and Tushman speak of the importance of leadership as they describe the informal organization and the people in their original model, but as a central theme for the course, it made sense to highlight leadership’s central role in organizational change and communication.

The Congruence Model helps us think about organizations and change in three ways.

- First, it provides a conceptualization of an organization as a dynamic system with interdependent components, which highlights the complexity surrounding change efforts within an organization. And is probably the reason why greater than 70% of organizational change efforts fail (Keller, S. and Aiken, C., 2009).

- Second, it gives us a way to think about change and how it impacts an organization—environmental factors tend to shape strategy, which, in turn, propels the transformation process and subsequent results.

- Third, for an organization to be effective and successful with change efforts, a good fit among its components is required from the environment, to its strategy, and the internal components (task, people, structure, and culture).

Want to Learn More?

[MUSIC PLAYING] GRAYCE CARSON: Hey, Rick.

RICK VANASSE: Hey, Grayce, how are you?

GRAYCE CARSON: I'm doing swell. How are you?

RICK VANASSE: Good, good, good. Good to see you.

GRAYCE CARSON: You too.

RICK VANASSE: Yeah.

GRAYCE CARSON: So lately, we've been talking about organization design models. And I've heard you mention the congruence model. Can you maybe go over that with us today?

RICK VANASSE: Absolutely. Yeah, no, that's great. It's a great model. So think about a key element of every CEO's job is creating competitive advantage. How do I capture the marketplace? How do I produce a better product or service than the competitor? And think about how often that has included an organization design, a redesign, or a restructuring of some kind or another. And then think about how often have those been successful and how often have those failed? And I hate to say it, but it's more the latter.

So what if there were a framework or a way of thinking about organization design that actually worked? So that is something that two folks that I've had the pleasure to work with, David Nadler and Michael Tushman, created, and that's called the congruence model. So I'd like to share that with you here today.

So what does David mean by congruence? So let me read to you his definition of congruence. And this comes from his book by he and Tushman called Competing by Design. So David says, at any given time, the components of an organization have a level of congruence, that is, the degree to which the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and structures of one component of the organization are consistent with and aligned with another.

So oftentimes you hear us talking about organizational alignment. That's really the core of what the congruence model is all about. So Grayce, here's a diagram of the congruence model. I'd like to break it down into its various components. So the first component in diagnosing an organization and looking for its alignment is to understand its broader ecosystem, the environment within which that organization is functioning. And we break that into two parts. We call them the puts. It's the inputs and the outputs.

Now, the inputs of an organization are the environment, the resources you have available, raw materials, financial, people, market. It includes the history of the industry, the history of the organization. It includes the technology. What is the leading edge? What is the bleeding edge? The outputs are at the other end of the spectrum.

And it is the expected outputs at three levels, at a system level, company as a whole, at a unit level, perhaps at a P&L within the organization or within a function, and at the individual level, each employee. So we talk about two components, the two ends of the spectrum, as going from the puts to the puts.

So the second component I'd like to talk about is strategy. And this is strategy given your understanding of the whole, understanding of the context, the inputs. Think of strategy at two levels. There's the corporate strategy, which is really about the decisions you want to make around your business portfolio, in other words, what businesses do we want to be in? How and where do we want to compete?

The second is the more detailed. And that's the business strategy. And the business strategy is, given each of those P&Ls, or businesses you've chosen to be in, how do you best configure the limited resources that you have to meet the demands, the opportunities, the challenges for that business for that market? So the strategy is taking what you've learned from the inputs and configuring it in a way that you can say, here's how we want to approach achieving our business results.

So Grayce, the third component is the transformation process as it is embodied in the organization itself. So think about it. Why does an organization even exist? It exists to take a product or service and transform it from the inputs to the outcomes or outputs. And as you can see from the detail here, there are four elements of the transformation process or four components of the organization.

So the first component is the actual work. These are the activities within the organization that drive its transformation, raw materials to a product, people's capabilities to a service. So performing this work is one of the primary reasons why an organization even exists. Our goal is to complete this work, get the work done, as efficiently and as effectively as possible with the highest quality output and at the lowest cost.

The second element are the people. The people are the ones responsible for the tasks, for the activities, for doing the work within that transformation process. And what we want to do is to ensure that the people have the necessary skills and capabilities and knowledge to do the work.

The second component of the people is we want, as a company, we want to be sure that their personal needs and desires are being met, that they want to continue to work here, that they feel as though they're getting a fair wage and recognition. And probably the most important component is that they're finding meaning in the work that they're doing.

So increasingly, meaning making is a critical part of the workplace and ensuring that people are finding ways in which they can be fulfilled and find meaning in the work that they're doing on a day to day basis. The third element of the transformation process, or the third element as you're designing an organization, is the formal organization. That's the structures, processes, and systems that we put in place that are necessary to organize and enable our people to get the work done, to make that transformation of our product or service.

So when you think about it, when you think about when people speak about going through a restructuring or a redesign, typically what they're talking about is the formal organization. It's the boxes and lines. It's who reports to who. Do we have enough of the right people in the right place? Is the reporting relationship correct? That's all very important stuff.

But if that's all you're doing in an organization design, you're kind of moving deck chairs around on the deck of the Titanic. And it's not going to achieve the results, overall results, that you're looking for. Instead, it's one key element. But that leads us to the fourth component of the transformation or fourth element of an organization. And that's the informal organization.

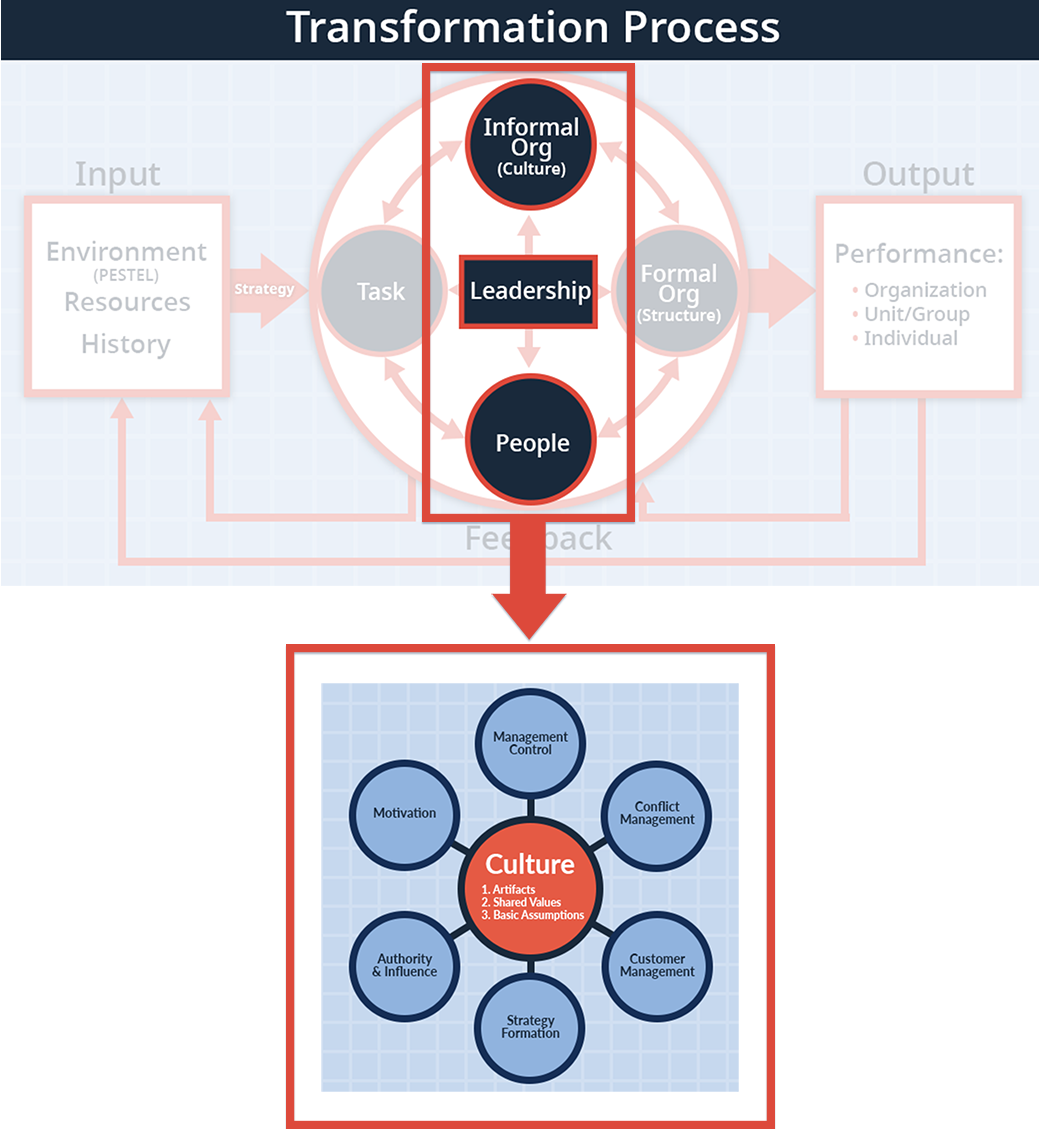

And the informal organization is perhaps the most important. Those are the unwritten rules and guidelines that exist that are powerfully influencing people's collective and individual behavior. Guess what we call that? Culture. And so the culture of an organization or the informal organization is where a lot of companies are spending time to build out their values, their expected behaviors. And that's great work. But again, it has to be in alignment with the formal organization, the people, and the actual work that you're doing. So it's alignment of these four things.

Now, think about most mergers and acquisitions. And if you read HBR or a lot of articles will speak to 70% of mergers and acquisitions fail. Why do they fail? It's not because of inadequate financial due diligence, or market due diligence, or business process integration. It's usually cultural fit. And so especially if you're looking at acquiring or selling with another organization, understanding the informal organization is key. And then it's aligning these four elements that's perhaps most important.

One thing that I and my fellow former Delta colleagues like to argue is that there's actually a fifth element to this model. And it sits right there in the middle of the four components. And it's called leadership. And if you think about what the role of the leader, particularly the role of the CEO, it's to understand this ecosystem, understand the environment within which you're functioning, those inputs and outputs. It's to articulate a clear corporate strategy, a clear business strategy around each element of that portfolio. And then it's to help people understand and reach alignment, congruence, around the other four elements.

So I think a key missing component in David's model is that fifth box in the middle called leadership. And then when you step back from this whole process and you say, so how does it all come together, it comes together best by a CEO meeting with their executive team, bringing conversation to the table, finding ways to bring further alignment conversation to the rest of the organization.

So any good organization design doesn't happen in a back office somewhere. It happens by involving as many people as possible in the right way to participate in creating the alignment across the organization. And a great principle to keep in mind for that is people tend to support what they help create. And that goes for organization design as well. So I hope that was helpful, Grayce, answered a few questions you may have had about what is the congruence model.

GRAYCE CARSON: Absolutely. Thanks so much, Rick.

RICK VANASSE: You're welcome. Take care.

GRAYCE CARSON: Bye bye.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

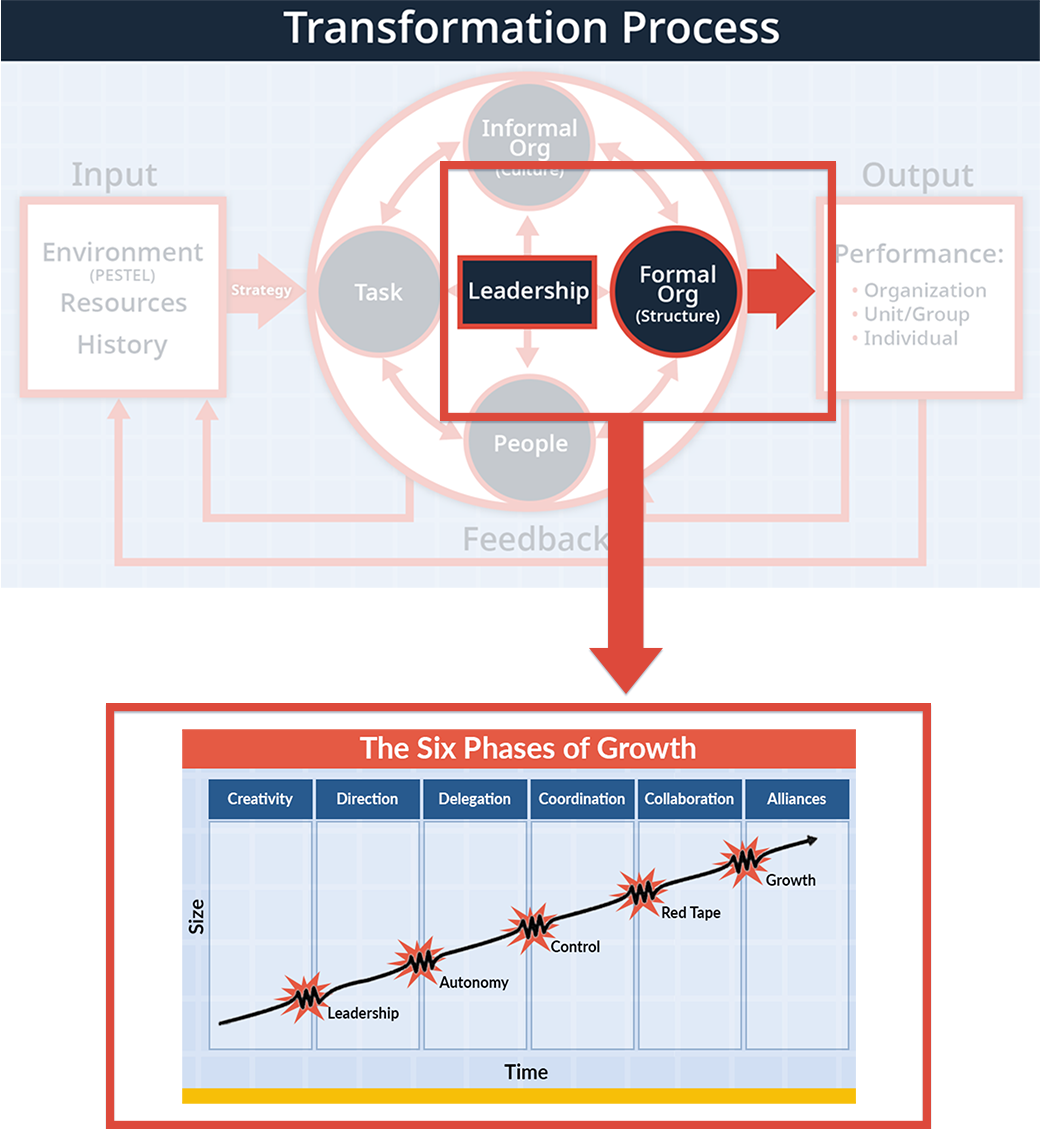

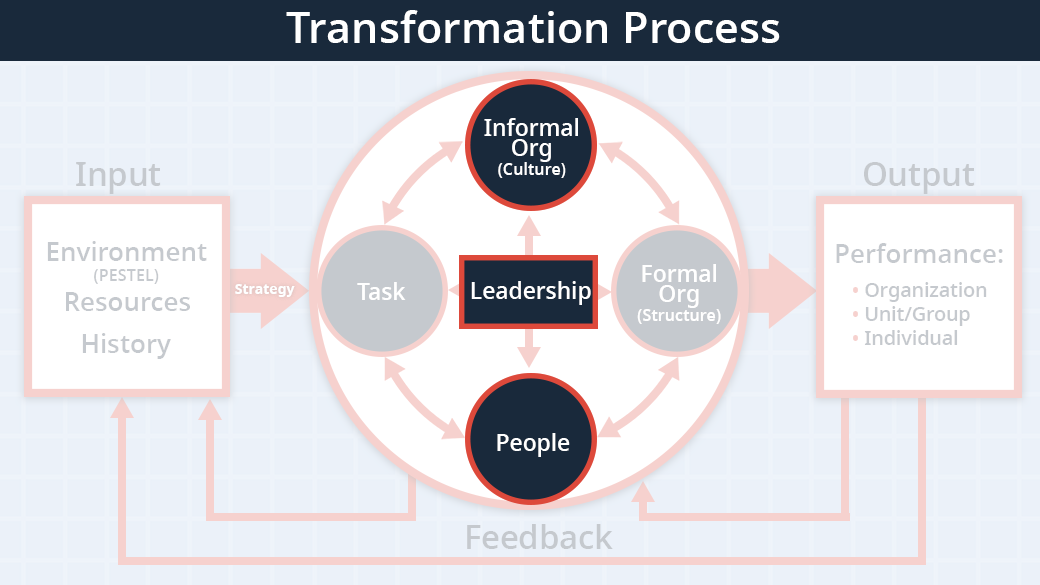

As an organizing framework for the modules in this course, the Nadler & Tushman Congruence Model provides a straightforward way to discuss the important aspects of an organization in terms of change and communication. However, the Congruence model as an organizing framework does not have the requisite detail for in-depth analysis of each topic, so various sub-models are imbedded to allow for a more nuanced analysis of these topics. Click the arrow to see how the Congruence and sub-models are used as guides for the design of the course.

.png)