MBADM816:

Lesson 1: Introduction to Organizational Behavior

Module 1 Overview

This course is about the human side of leading and managing people in organizations. The body of conceptual and theoretical knowledge in this course primarily emanates from the field of organizational behavior (OB). This module provides a basic overview of the field—the basic disciplines of knowledge from which it arises, its diverse content areas, and its varied levels of analysis. You will engage in a team-building exercise to get off to a good start as a team and to develop intra-team trust.

Module Goals

- Understand the importance of the concept of cognitive complexity for managers and leaders.

- Gain an understanding of the meaning of team building, specifically of how to develop fast trust in a team context.

Module Objectives

After completing this module, you should be able to do the following things:

- Summarize the disciplines contributing to the study of organizational behavior.

- Define organizational behavior and identify the primary behavioral disciplines contributing to this field.

- Identify the diverse levels of analysis encompassed by the study of organizational behavior.

- Describe how OB concepts are key to understanding the diverse facets and processes present in all complex organizations.

Module Readings and Activities

By the end of this module, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Course Schedule.

Cognitive Complexity, Mental Maps, and Why Learning This Course Content Is Important!

Please take out a blank sheet of paper. Set a timer to four minutes. Now, draw either the human body, filling in and labeling as much detail as possible relative to the organ systems, or a map of Europe, filling in and labeling as much detail as possible regarding names of countries (and cities, if you have time).

Once you have completed your drawing, click on the arrow below that corresponds to what you chose to draw. This will give you feedback regarding how well you did.

Now, what you drew—the body or Europe—represents a graphic, visual depiction of your inner knowledge. It represents the state of cognitive complexity that you currently possess regarding these two domains of knowledge (the body or Europe). The point of this little exercise is to impress upon you the importance of having a good "mental map" of the world of organizational behavior. For you to become a good manager and leader, it is important that you attain a sufficient degree of cognitive complexity relative to the processes and variables that come into play in the study of organizations. For a portion of this course, you will be engaged in learning concepts and variables relevant to human behavior in organizations. These are important because they give you a map of the territory!

Think of it this way: If you were about to undergo surgery, would it be important to you that your surgeon have a good working knowledge of anatomy? Of course. The same holds true for managers and leaders. It is important, for example, to have a good working knowledge of the nature of groups and group dynamics—how and why groups form, what variables (such as norms, cohesion, and team composition) are requisite to high-performing groups, the potential pitfalls of group decision-making, and so on. The same holds for all of the content areas that this course covers.

But also, wouldn’t it be nice if your surgeon knew a little bit more than simply the locations of different anatomical parts? You would likely expect him or her to have skill, acumen, motivation, conscientiousness, and a good working knowledge of how all the body systems and parts work together. Consequently, while the above exercise is designed to impress upon you the intrinsic importance of knowing the concepts and variables of organization management, in this course you will be engaged in a number of exercises and discussions designed to provide you with various tangible skill sets that managers and leaders need.

Next, take out another piece of paper and put the words Organizational Rehavior right in the center. Then, draw a number of different lines (perhaps eight to start) radiating out from the center. At the end of each line, put some of the following content-area labels: individual differences in organizations, how to motivate employees, group dynamics, power and politics, conflict management, emotional intelligence, leadership, and so on. How much knowledge do you presently possess regarding each of these content areas? If you were asked to fill in or list (as with the map of Europe) everything that you currently know, how detailed would your visual map be? In other words, what is your current mental map, your present degree of cognitive complexity regarding organizational behavior? Throughout this course, you'll be able to fill it in further.

Disciplines Contributing to the Study of Organizational Behavior

You may recognize a number of social and behavioral sciences as the origins of the organizational-behavior issues we will discuss, especially in the early parts of the course. Think of OB as borrowing the findings from these fields and applying them to explaining, predicting, and controlling human behavior in formal work settings. The origins are interesting to the extent that they will help you better understand the modern-day discipline of organizational behavior—its current state is illuminated by its history and foundations.

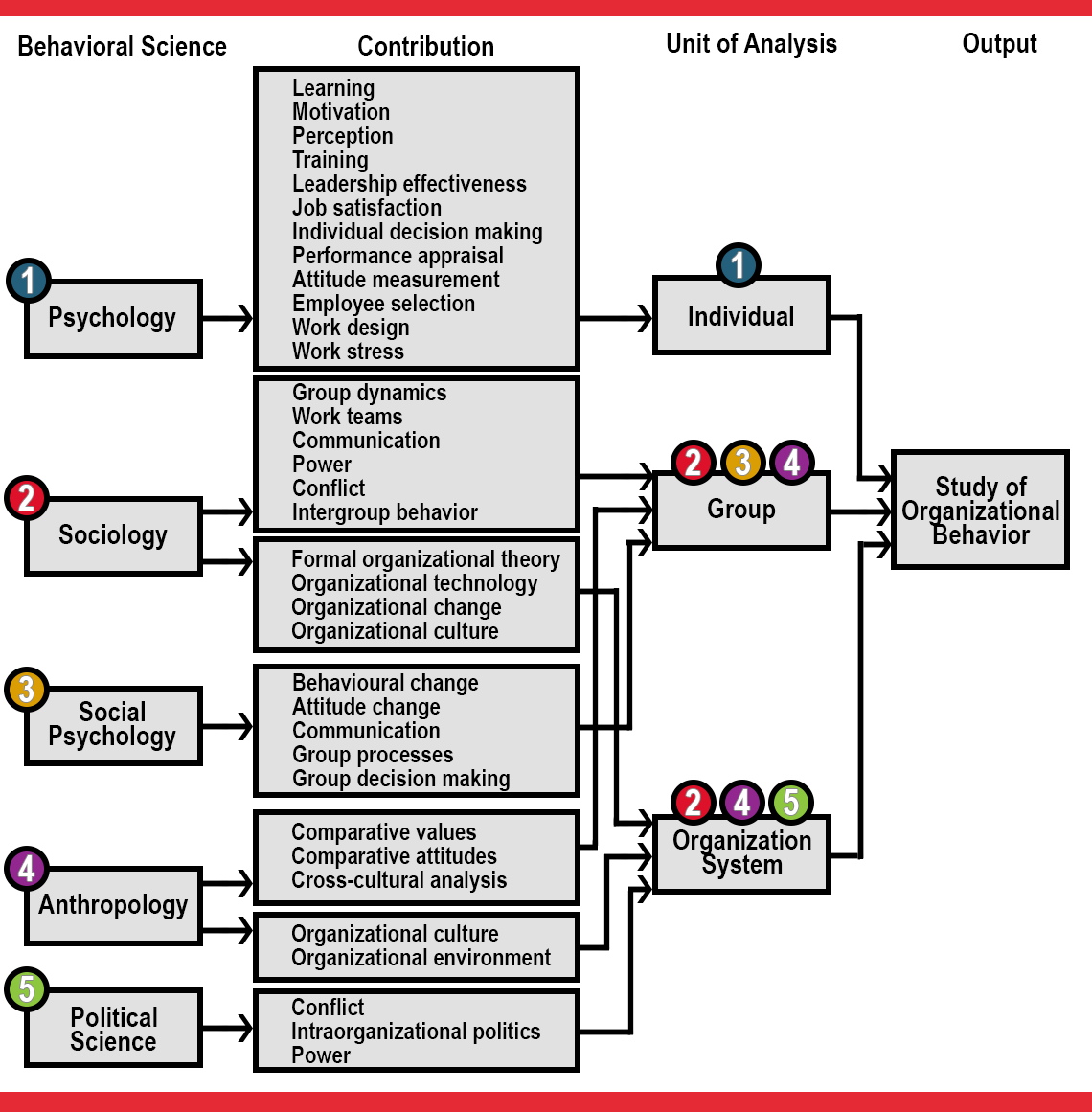

Psychology makes a strong contribution to many of the micro- or individual-level issues we will discuss. Also notable are contributions from sociology, social psychology, political science, and even anthropology. This makes the study of organizational behavior interesting and vibrant. Rather than being closeted by the confines of a narrow disciplinary lens, we can draw on any discipline that enables us to better understand organizations and the behavior of people in them. Figure 1.1 illustrates some of these related disciplines.

Levels of Analysis and Interactional Psychology

One basic way of getting an overview of the various topics and elements covered in this course is to think about levels of analysis, ranging from micro to macro. At one extreme, we analyze on an individual level, studying personality differences, perception, and individual decision-making. We can then move up the levels to study groups and group dynamics. Finally, at an organizational level of analysis, we encounter more global topics, such as organizational structure and culture.

A second way of approaching the subject matter is to understand how the various concepts interact with one another. Kurt Lewin's interactional psychology perspective is very helpful here. His view (a widely held one) is that human behavior is a function of differences in individual characteristics and in reactions to situations. Put more simply, behavior ( B ) is a function of the person ( P ) and his or her interactions with the environment ( E ), expressed as B = f ( P , E ). If we refine this view and focus on organizational behavior and performance, any number of person and environment variables might be listed and plugged into the formula. Relevant organizational variables might include, although are not limited to, things like the interaction between someone’s personality style ( P ) and the design of their job (which, in this case, is external to them, so it’s an environmental variable). Or, how one’s attitudes ( P ) interact with the motivational levers the organization uses (E, the reward system).

Organizational Society

We live in an organizational society. In traditional historical societies, family structure acted as the center of life, but in modern developed economies, organizations are central. Think about it: We are born in organizations (hospitals), are educated in organizations, worship in organizations, work in organizations, play or enjoy sports in organizations, are entertained in or by organizations, and will (probably) die in an organization. And, when the time comes for burial, the largest organization of all—the state—must grant official permission (Etzioni, 1964).

One of the hallmarks of a healthy, democratic society is that it tends to be characterized by a proliferation of various organizations (i.e. not only private sector organizations but also a proliferation of volunteer and non-profit organizations). While the focus of this course is on business organizations, it important to understand that all organizations share a number of common features and structures. Anytime you get a large group of people engaged in formal, goal-directed activity, a number of similar dynamics emerge. For example, all organizations

- have a culture,

- contain individual differences relative to personality traits or attitudes,

- emphasize the importance of goals and goal measurement,

- have formal objectives,

- involve groups and ensuing group dynamics, and

- have a need for leadership.

Whether they are profit-making, nonprofit, charitable, volunteer, or governmental agencies, all organizations have—at a conceptual and structural level—far more commonalities than differences. For example, on the surface, you might think that the FBI and the Catholic Church are very different organizations. They are. And yet, if you look at them through various conceptual lenses—such as how the organization is formally structured, how culture functions, and so on—these two seemingly divergent organizations actually share a number of common features.

One way of appreciating this commonality among different types of organizations is to consider what happens when any organization gets large. Consider the example of someone who opens a small mom-and-pop restaurant. (A lot of today's major corporations started out as small entrepreneurial enterprises.) Let’s say they have a small restaurant with a very small staff. "Mom" or "Pop" does all the cooking, but the owner knows all the recipes, knows all the employees by name, and so forth. The business prospers. The owner decides to open a second location, which in turn prospers. Before long, they now have a medium-sized restaurant chain, with 40 locations spanning six different states. Suddenly, this is a big, somewhat-complex organization—and, as with any large organization, it needs structure, rules, systems, and procedures For example, this restaurant chain will need standardized recipes and menus across locations, as well as formal job descriptions for employees. It will need accounting procedures, a supply chain, formalized compensation and reward plans, formalized training and evaluation procedures, and systematic hiring and recruiting practices. These types of structuring processes occur even in nonprofit or charitable organizations.

Finding Your Inner Leader

As noted, beyond the modules dealing with conceptual content related to organizational behavior, this course also offers a number of exercises for exploring your inner leader and nurturing your leadership competencies. While we typically think of leadership as an outer-directed activity, acting in the world and acting upon others, an important facet increasingly recognized in the literature is self-knowledge—it is this important path that the course endeavors to lead you down as you learn how to be a proficient leader.

Reference

Etzioni, A. (1964). Modern organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Module 1 Activities

Module 1 Synchronous Session

These live sessions are not required but are intended as supplemental learning experiences that delve deeper into each lesson. If you choose not to attend a live session, you should watch the recording at your convenience.

All synchronous sessions will be recorded for later viewing. To view recordings, select Media Gallery in the navigation menu.

To join the synchronous session, select Zoom in the course navigation window, and select "Join" for this session. Details and support are available in the Zoom Video Conferencing module.

Agenda

This is an introductory session. Your Instructor will provide an overview of how the course is structured, team assignments and responsibilities, and all other assignments that are due throughout the course. Students will have the opportunity to ask any other questions they might have regarding the course content, assignments, grading, the Instructor's background, and so on.

Team Essay 1: Virtual Team Building

In this assignment, you may not use artificial intelligence (AI) for any purpose. See Key to AI Use for more information.

This week your group will design and implement a team building exercise. This can be challenging for your first week (which is why you have until Tuesday midnight of week 2 to complete it). In overall terms this course is very reasonable in terms of workload, this just happens to be one of the more intense weeks. And the exercise is important in that it will prepare your team for ensuing group projects.

Two of the assigned readings (Aron, 1997 & “Practice 36 questions”) are a research study, and a synopsis of the same. You need not read the study in detail, primarily focus on the first part of the Appendix (i.e. not the ‘small talk’ condition). This describes an experiment on enhancing interpersonal closeness. You should either: 1) adapt this experiment as you deem best suited for a team building context, including any modifications/additions/deletions to the questions (how or how much or how little you modify is up to you), or 2) come up a team building exercise of your own choosing.*

Whichever option you choose, as you implement your exercise it should rest on two pillars: 1) Self-disclosure and 2) Safety. Self-disclosure means sharing something beyond the superficial – such as dreams, fears, goals, preferences, experiences, etc. Self-disclosure can strengthen relationships and build trust. Safety means that all members feel safe, and the group supports psychological safety. No one feels pressured to share, and any sharing is received with respect and acceptance by the group.

The main point: rather than just ‘getting to know one another', a good team building exercise structures interaction in a way that can speed up and deepen the ability of the group to break the ice, develop trust, and move forward as a team. As such, team building can take a group of relative strangers and help them form into a team rather quickly. Indeed team building can be thought of as a form of technology. While we stereotypically think of technology as a system of rules or procedures for transforming objects in the material world (like iron ore into steel), technology can also be thought of as acting upon humans. For example, psychotherapy is a technology; it’s a set of techniques and practices designed to help individuals optimize their potential. Mindfulness or meditative practices are also a technology – designed to help regulate and strengthen our attention. Indeed, Marine boot camp can be thought of as a form of technology. It is a set of routines and practices designed to take a disparate collection of individuals and mold them into a relatively homogeneous group with a shared sense of identity and norms.

If you take this assignment seriously, it will help your team on ensuing team-based assignments. Groups that bond well and develop trust perform better in the long run. (And while you should take this seriously, it’s also okay to have fun; Humor is an element known to be conducive to human bonding!) This assignment also provides you with insight into the technology of team building, knowledge you can apply in your professional lives.

Don’t get bogged down in process. Spend some time in idea generation (brainstorming regarding your exercise). Then implement. Then write it up!

Deliverable: a 450- to 500-word essay describing the essence of your chosen exercise, how it went, what you feel were the results. Don’t get too bogged down in conveying all the details of your exercise. What is important is to provide a rich sense of the processes that unfolded in your group and how the exercise worked for your team. Be authentic; if you feel your exercise fell short, just say what happened. Write something that is interesting to read. Please explicitly comment on how your exercise rested on the pillars of disclosure and safety. And, per the 3rd assigned reading (Frei, 2020), say whether (or to what extent) you feel your team developed trust, and why that might matter.

Your essay should be written out with good flow (i.e. no bullet points). Post in two places: 1) upload it here so your instructor can assign a grade, 2) post it in the Module 1 Discussion: Virtual Team Building (as a post not an attachment) so others can view your team’s process. Put # of words in parenthesis at end of document (references don’t count as words).

*If you choose option #1 you can ignore the 'manipulations' done in the study. The bottom line is to come up with three sets of questions, each set containing successively deeper or challenging questions, and that it is adapted for a team as opposed to a dyad.

In that your team will be meeting together, you also might spend a short amount of time discussing team norms, aspirations, member proficiencies, or so on.

| Criteria | Full Marks | No Marks | Points Possible |

|---|---|---|---|

| This criterion is linked to a Learning Outcome Draws appropriately on concepts or ideas from the text and/or course material. Demonstrates critical analysis, creativity and insight, and self-reflection as appropriate to the question. | 60 pts | 0 pts | 60 pts |

| This criterion is linked to a Learning Outcome Writing: Are the mechanics of writing appropriate, in terms of sentence construction, verb tense, spelling, awkward constructions, formatting guidelines, etc.? Is the answer well written, in terms of its logical organization and flow? I.e. does it read well, is it concise, etc.? | 30 pts | 0 pts | 30 pts |

| This criterion is linked to a Learning Outcome Does the student go above and beyond a 'good' answer by demonstrating superior critical analysis, insight, reflection, etc. Is the writing captivating to read? | 10 pts | 0 pts | 10 pts |

Discussion Topic: Module 1 Discussion: Virtual Team Building

In addition to submitting your team essay as an Assignment, so that it can be graded, please have one member of each group post their group's Essay to this discussion forum (please copy and paste as a post that is viewable to everyone, not as an attachment). There is no individual discussion requirement this week. Having each team's essay posted here merely provides everyone with an opportunity to see what transpired within the other teams, how they approached the task, what teambuilding/trustbuilding technology they came up with, and so on. You are welcome to comment in response to any team's post, but there is no requirement to.