MBADM822:

Lesson 1: Introduction to Supply Chain Strategy

Lesson 1 Overview

This lesson introduces the concept of supply chains and the field of supply chain management, focusing on the importance of managing both inbound and outbound partnerships. It explores supply chain strategies, the impact of globalization on supply chains, restructuring, and the integration of ethical and sustainable practices. Additionally, the lesson covers strategic planning processes, including operations strategy and tools such as the Strategic Profit Model and the Balanced Scorecard.

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to do the following things:

- Describe the key concepts of supply chain management and the decision-making process involved.

- Explain the impact of globalization on supply chain management.

- Describe the evolution of supply chain management over time and identify some of the emerging trends.

- Describe how an operations strategy is formulated and evaluated.

- Explain the strategic planning process for both goods and services supply chains.

- Explain the process for evaluating firms' supply chain strategies.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Course Schedule.

Introduction to Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management has become part of the business vocabulary, given the drastic changes in the business landscape brought on by globalization and the rapid change in the business climate that occurred in the 1990s. Business success today means forging alliances with suppliers and customers and recognizing that the only thing that stays the same is change.

A company’s supply chain is inextricably linked with its internal operations function, which transforms inputs (such as materials, energy, information, capital, and labor) into goods and services, thereby creating value. The organizations comprising any supply chain are primarily involved in value-adding activities; therefore, a supply chain is frequently referred to as a value chain. Value is added to the product, service, or project as it progresses through the various stages of the chain.

The supply chain concept began as a method of internal integration among procurement, warehousing, and physical distribution. Logistics cost analysis centered on the concept of total systems cost, the goal of which was to reduce the overall cost and prevent suboptimization of the overall logistics function. At first, managers focused on improving outbound logistics because of the higher value placed on finished goods. In addition, customer service and satisfaction depended upon efficient outbound logistics practices. Inbound logistics was added later, as deregulation of the transportation industry allowed logistics professionals to focus on the coordination of inbound and outbound movements. Figure 1.1 shows the logistics function within the organization. The integrated logistics concept sought to provide these functions seamlessly. The focus was on total systems costs and managing the trade-offs to arrive at the lowest physical distribution cost.

Figure 1.1. Logistics Functions in an Organization

Adapted from the Center for Supply Chain Research, Penn State

Today, supply chain management has become a way of doing business—a framework within which other business functions occur: "Supply chain management is primarily concerned with the efficient integration of suppliers, factories, warehouses, and [stores] so that merchandise is produced and distributed in the right quantities, to the right locations, and at the right time" to all stakeholders so that we "minimize total system cost [while satisfying customers'] requirements" (Mallik, 2010, p. 103)

Today, supply chain management has become a way of doing business—a framework within which other business functions occur: "Supply chain management is primarily concerned with the efficient integration of suppliers, factories, warehouses, and [stores] so that merchandise is produced and distributed in the right quantities, to the right locations, and at the right time" to all stakeholders so that we "minimize total system cost [while satisfying customers'] requirements" (Mallik, 2010, p. 103)

Supply chain management can be defined as “the design and coordination of a network through which organizations and individuals get, use, deliver, and dispose of material goods; acquire and distribute services; and make their offerings available to markets, customers, and clients.” (LeMay et al., 2017).

Influence of Globalization

Currently, more than two-thirds of businesses are engaged in global markets through global operations or global financing or as partners in global supply chains. Not only can large multinational companies access global markets, but small businesses that typically lack resources can also now cater to the needs of consumers in other countries.

This all happened due to the globalization of markets. Globalization means that a business can sell in a foreign country, manufacture products in a foreign land, buy materials from an overseas supplier, operate as franchises, or partner with a foreign company. As a result of globalization, there has been a proliferation of strategic partnerships, joint ventures, licensing agreements, research consortia, direct marketing agreements, and, above all, the formation of global supply chains among global business partners. The driving forces for globalization of businesses are lower costs, entry into global markets, quick responses to changes in demand, reliable sources of supply, and access to cutting-edge trends and state-of-the-art technologies. These forces have led to the emergence of two phenomena: offshoring and outsourcing.

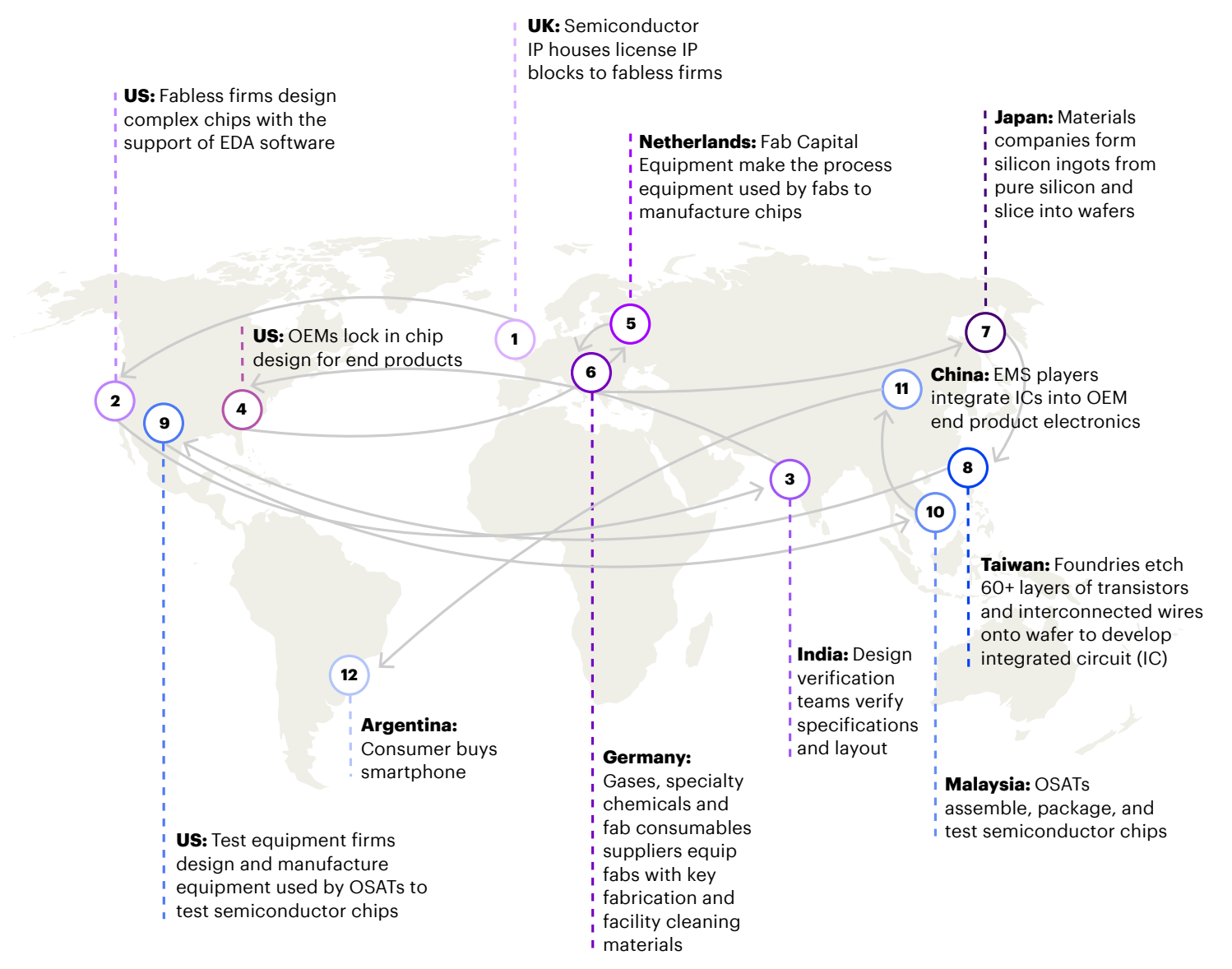

Today, semiconductor manufacturing is getting a lot of attention. We use semiconductors not only in our personal computers and phones but also in numerous smart devices within the household and our cars. (A modern car can have 1,000 to 3,500 semiconductors.) Figure 1.2 shows a typical flow within the global semiconductor value chain.

Current and Emerging Trends

In this era of global competition, companies are facing challenges and tradeoffs that make their operations and supply chains increasingly complex. Given that many companies lack the necessary sophistication and flexibility in their current operations and supply chains, they are ill-equipped to cope with the challenges of an uncertain and volatile global market. In other words, what makes us profitable today may not be commercially viable next year.

This inherent instability will expose many companies that conduct business globally to a steady set of new challenges. Some of these challenges, like turbulent trade and capital flows caused by global economic downturn, are likely to become a perennial supply chain concern. Other challenges with long-term supply chain implications include rising wealth in developing countries (such as emerging central and eastern European countries) and the availability of reliable suppliers from these markets. Although many of these challenges are beyond a company’s control, the senior executives responsible for managing their operations and supply chains need to be aware of and capitalize on certain trends.

The following chart shows how global connectedness (red)—in terms of trade (black), information (blue), capital (green), and people (purple)—evolved over time.

Introduction to Supply Chain Strategy

A supply chain strategy provides a road map for creating finished products and sending them to customers in a timely manner. It focuses not only on the operations of the organization, but also on the supply chain partners to fulfill specific supply chain objectives, such as ensuring a seamless flow of products, minimizing operational costs, maintaining product quality, and improving supply chain efficiencies. The scope of supply chain strategy includes procurement of raw materials, transportation, manufacturing of the product (or provision of the service), and distribution of the product.

In today’s global supply chains, supply chain partners are becoming increasingly interconnected and interdependent. Resources, currencies, information, and risks cross national borders and change hands across multiple markets. As a result, supply chain partners are more directly dependent on each other than ever before. In recent years, we have witnessed some low-probability but high-impact events such as a global pandemic, geopolitical tensions and war, and severe weather interrupting the flow of goods and services from one region to another and significantly disrupting global supply chains. In order to be a key player, companies have to rethink and revamp their strategies to mitigate inefficiencies in their global supply chains.

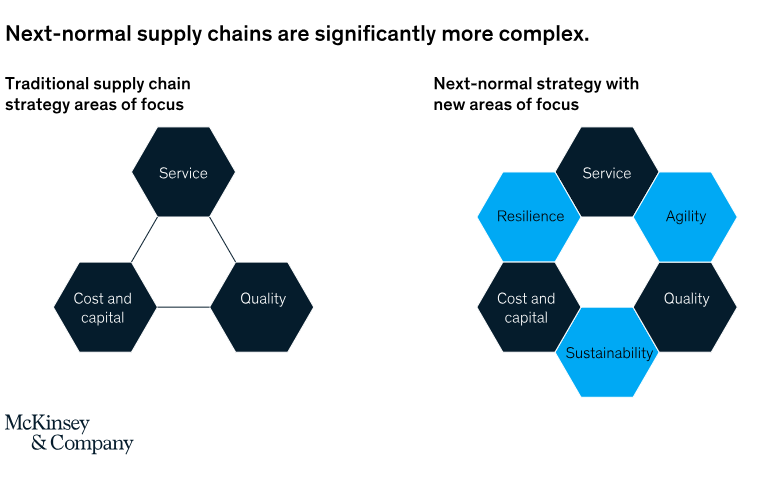

According to a McKinsey study (Henrich et al., 2022), it is now important to consider three new priorities in formulating a supply chain strategy, alongside the traditional objectives of cost/capital, quality, and service. These new priorities are resilience (i.e., the ability to mitigate disruptions), agility (i.e., the ability to meet rapidly evolving customer needs in a timely manner), and sustainability (i.e., the transition to a clean and socially responsible economy).

The Different Levels of Strategy Formulation

Strategic planning in most companies follows a hierarchy of three levels:

- corporate strategy,

- business strategy, and

- functional strategies.

All three of these levels are closely linked, and strategic planning at a higher level of the hierarchy influences planning at the lower levels, as shown in Figure 2.1 (Strategic Planning Levels) on page 36 of the Venkataraman and Demirag textbook.

Corporate Strategy

A number of large conglomerates own a portfolio of businesses. For such companies, corporate strategy is at the highest level of the strategic planning hierarchy. This strategic level, which is the responsibility of top management, is the broadest in scope and attempts to address the fundamental question of which industries and markets the firm should enter and compete in. In addition to the primary objective of improving the economic performance of the firm, the scope of a corporate strategy also includes the concept of sustainability and the three performance targets. Also known as the triple bottom line of economic value, social responsibility, and environmental values, this concept has three overlapping components of sustainability, as shown in Figure 2.2 (Triple Bottom Line) on page 37 of the textbook.

Business Strategy

While corporate strategy addresses the question of what markets we should be in, business strategy addresses the question of how we should compete within them. Business strategies have a shorter time horizon and more detail than corporate strategies do. Formulating and implementing business strategy is the responsibility of those operating individual strategic business units (SBUs). Although it varies from company to company, the organization of SBUs is usually along product lines, market segments, or geographic dimensions.

Business strategies focus on developing and leveraging the core competencies or competitive strengths within each SBU, such as the ability to produce high-quality or low-cost products, to achieve a well-defined higher-level goal or objective. The decision process aims to arrive at a competitive plan in terms of which products or services to offer in which market segments and when to offer them. The ultimate goal of the business strategy of each SBU is to ensure that its activities are in alignment with the overall corporate strategy.

Functional Strategies

Functional strategies focus on coordinating and integrating the activities and resources within each functional area (marketing, operations, finance, accounting, etc.) so that they contribute to and support both the higher-level business strategy of individual SBUs and the overall corporate strategy. These strategies, which are developed and implemented by lower-level managers in the corporate hierarchy, have shorter time horizons and are more specific and detailed in terms of action plans than the higher-level business strategies.

Operations Strategy

Among the various functional strategies, the operations strategy is the most relevant to formulating the company’s overall global supply chain strategy. Keith (2016) describes operations strategy as "the nerve center of any company. It’s what takes the message from the brain (corporate strategy), translates it, and makes sure the muscles (people and process) perform what the brain intended."

Each individual company within a supply chain, whether it is a manufacturing or service organization, needs to develop an operations strategy to provide a road map and a decision framework for its internal operations. Operations strategy is usually formulated in terms of the competitive priorities or distinctive competencies of the firm, such as cost, quality, flexibility, time, and innovation. Walmart, for example, competes on the basis of cost (everyday low prices); therefore, its operations strategy is geared toward improving the efficiency of its retail operations and its supply chain.

These distinctive competencies also typically constitute the objectives of the operations function, the purpose of which is to effectively use the firm’s resources to achieve competitive advantages in the marketplace. For example, if a company's competitive business strategy is based on on-time delivery or delivery speed, then its operations strategy will focus on promoting speed. Every operational activity of the company is geared toward this objective of speed.

Formulating an Operations Strategy

A company's operations strategy is based on four critical elements:

- its customers,

- the nature or features of its product and process,

- its operational capabilities or critical success factors (CSFs), and

- its distinctive competencies or value proposition.

Firms identify the fourth element—the distinctive competency through which they create value—by finding the ideal match among the other three elements—customers, product and process features, and operational capabilities. Figure 2.3 (Four Elements of an Operations Strategy) on page 26 of your textbook shows how these four critical elements constitute the cornerstones of an operations strategy.

Formulated through the appropriate fit among these elements, a viable operations strategy is attained by focusing operational capabilities on achieving the distinctive competency in the product or service that delivers the value desired by the customer. However, changing market trends, technologies, customer bases, product life cycles, and competition can cause a mismatch among the elements. When such a mismatch occurs (and depending on what critical element caused the mismatch) companies need to consider alternative courses of action.

Another important feature in formulating operations strategy is the need for tradeoffs and focused operations. As a company cannot simultaneously compete on every dimension of its distinctive competencies, tradeoffs are necessary. For example, a company with a distinctive competency of offering customized premium-quality products cannot simultaneously use a low-cost strategy.

Formulating and implementing an operations strategy requires a company to make both structural and infrastructural decisions. The structural decisions to be made are in the areas of process and capacity, facilities, and technology. The infrastructural decisions to be made relate to the areas of workforce, sales and operations planning, control systems, product/process innovation, and organizational structure.

Here is a short video on how Starbucks’s evolving operations strategy uses its operational capabilities to improve customer service.

Measuring Performance

The performance of a company's operations strategy is evaluated based on the extent to which it has supported and achieved the goals and objectives of the firm’s corporate and business strategies. Doing so requires a measurement system that can provide meaningful feedback on areas that need improvement. Two such measurement systems are the strategic profit model (SPM), also known as the DuPont model, and the Balanced Scorecard.

Service Operations Planning

Service organizations, like manufacturing, also compete based on the core competencies of cost, quality, flexibility, time, and innovation. Therefore, managing service operations also requires a strategic approach. The strategic planning process for service operations can be captured in the hierarchical planning framework shown in Figure 2.4 (Strategic Framework for Service Operations) on page 45 of your textbook. It consists of three levels: strategic positioning, service operations strategy, and tactical execution. Service operations add a fourth component to this framework that affects all three levels: a continuous improvement cycle.

Supply Chain Strategy

Increasing globalization and customer expectations during the 1990s and 2000s have led to significant changes in the competitive priorities of firms. In order to be competitive in the global marketplace, companies now have to compete in not just one, but multiple dimensions of their distinctive competencies (cost, quality, flexibility, time, and innovation).

Unfortunately, no company can dramatically improve its operational capabilities in these multiple dimensions by utilizing its own existing resources. Therefore, companies have realized that in order to compete in the global arena, they have to rely on their supply chain partners (such as suppliers, wholesalers, retailers, and transportation services) and leverage their resources and operational capabilities. A company needs to integrate its internal operations, as well as its own operations, with its key supply chain partners. Therefore, a firm’s operations strategy should not only align with its own business strategy but also with the operations strategies of its partners within its supply chain. Furthermore, the supply chain partners working together must also develop a supply chain strategy for the overall supply chain that is both consistent with and supportive of the competitive strategies of the individual partner firms within the supply chain.

Based on the business strategy road map, which delineates the overall direction the organization wants to take, a supply chain strategy focuses on the organization's actual operations and its supply chain partners in order to achieve a specific supply chain objective. For example, in a given market, if a company’s business strategy calls for competing on the basis of low cost, then the company needs to develop a supply chain strategy that focuses on reducing the costs in its supply chain by formally integrating its operational components of logistics and distribution, manufacturing, and inventory management.

Here is a video on the complexity of grocery supply chains that shows how grocery stores use a global network of supply chain partners to bring products to local stores.

Formulating and Implementing Global Operations and Supply Chain Strategies

On the previous pages, we discussed the operations strategy and the supply chain strategy as separate topics. However, in a global business environment, these two strategies are inseparable; therefore, we have to take a holistic view and discuss approaches for developing an integrated global operations and supply chain strategy.

The key challenge, then, is to acquire goods from emerging markets, where manufacturing is less expensive, in order to meet the demands of established markets, like service and time-to-market standards. To meet this challenge, global companies need fully integrated strategies that capitalize on the low-cost sourcing and manufacturing options available in emerging economies so that they can stay ahead of competition and increase productivity.

Specifically, companies that intend to expand their international customer base may need to redesign specific product portfolios, approach new production channels, or consider make-or-buy strategies and back-office capabilities. Conversely, companies that are forced by emerging competition to realign their cost targets at a global level require an entirely new strategy for sourcing, manufacturing, and distribution. In addition, these companies must also ensure that they do not compromise other strategic objectives, like time-to-market and customer service targets, as they leverage opportunities in low-cost countries. In order to develop and implement a viable integrated global operations and supply chain strategy, every company needs certain capabilities.

Sustainable Supply Chain Strategy

Implementing a sustainable supply chain strategy has become increasingly important as organizations strive to reduce their environmental impact, ensure ethical practices, and offer products/services in a responsible manner. A recent survey of supply chain executives (Executive Focus on Supply Chain Sustainability | EY - US) reveals several key challenges in integrating sustainability in supply chain operations. While the executives admit the need for a comprehensive, ROI-backed approach to sustainability, many organizations struggle with the lack of visibility and measurement capability of sustainable operations. While many organizations are prioritizing sustainability, they often lack a clear business strategy for sustainable supply chains. In addition, the survey emphasizes that supply chain sustainability initiatives should consider the end-to-end value chain, including raw material sourcing, product design, logistics, etc. Supply chains for many products are long, complex, and global. However, considering a broader scope is still essential for capturing the full benefits of sustainability initiatives. Nickel and cobalt, essential for lithium-ion batteries, and power devices ranging from smartphones to electric vehicles (EVs). The following two paragraphs discuss the challenges of incorporating a sustainable supply chain strategy for sourcing nickel and cobalt.

Indonesia produces nearly a third of the world’s nickel. However, its nickel-rich coastal areas are devastated by the environmental and social consequences of mining. Degradation of ecosystems in once-picturesque villages in Indonesia, pollution of its water sources, and displacement of local populations create a contrast between green energy revolution and its underlying environmental costs. You are encouraged to watch the short film titled From Dreams to Dust which portrays the impact of nickel mining in Indonesia.

Environmental damage from cobalt mining has affected another country on another continent. Mines of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) supply 75% of the global requirement for cobalt (Zuckerman, 2023). Cobalt boom has come with a significant loss of human lives. Thousands of miners, including children as young as five, live in hazardous conditions as exposure to toxic cobalt dust causes birth defects, cancers, and respiratory illness. Cobalt contamination has damaged the region’s air, soil, and water. As consumers become increasingly aware of the social and environmental impact of their devices, there is a growing call for companies to adhere to sustainable practices throughout their global supply chains.

Lesson Summary

This lesson introduced the concept of a supply chain, the field of supply chain management, and the development of supply chain strategy. The organizational supply chain is made up of numerous inbound and outbound partners, all of whom must be managed for optimum performance. Effectively managing a supply chain requires an integrated, broad external perspective that understands the nature of the competition, the suppliers, and customer management and a careful internal view of an organization's operations function that effectively and efficiently produces goods and services that exceed customer expectations.

This lesson also discussed the impact of business globalization on a company’s supply chain, along with the challenges and opportunities it offers to companies. It concluded by discussing some of the emerging issues in the field of supply chain management, such as the need for restructuring the supply chain and incorporating ethical and sustainable practices into its management.

Strategic planning is the process that sets the future direction for an organization. It is comprised of a hierarchy of strategic levels: corporate strategy, business strategy, and functional strategies. One of the important functional strategies is the operations strategy, which attempts to create value by balancing four key elements: customers, operational critical success factors, product factors, and a firm’s core competencies. The strategic profit model (SPM) and the Balanced Scorecard are two of the tools that can be used to evaluate an operations strategy. Service organizations develop an operations strategy using a hierarchical planning framework that consists of three levels: strategic positioning, service operations strategy, and tactical execution, with a continuous improvement cycle as a fourth component that affects all three levels.

In addition to developing an operations strategy, companies also need to develop and implement a supply chain strategy to fully support their business strategies. All elements of the firm’s operations strategy must be fully integrated into the supply chain strategy in order to realize the strategic objectives of providing clear directions that maximize efficiencies within the supply chain and reduce operational costs. The supply chain operations reference (SCOR) model can be used to evaluate supply chain performance.

In order to formulate and implement viable integrative global operations and supply chain strategies and manage the risks related to them, companies need to develop certain key capabilities. Increasingly, companies are developing corporate strategies that incorporate sustainability practices in order to create environmental and social value in addition to the traditional economic value.

References

Henrich, J., Li, J., Mazuera, C., & Fernando, P. (2022). Future-proofing the supply chain. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/future-proofing-the-supply-chain

Keith, S. (2016). Operations strategy? What operations strategy? Medium. https://stevenkeith.medium.com/operations-strategy-what-operations-strategy-e56e4232b9af

Mallik, S. (2010). Customer service in supply chain management. In H. Bidgoli (Ed.), The handbook of technology management, supply chain management, marketing and advertising, and global management (Vol. 2, pp. 103–118). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

LeMay, S., Helms, M. M., Kimball, B., & McMahon, D. (2017). Supply chain management: the elusive concept and definition. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 28(4), 1425–1453. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-10-2016-0232

Zuckerman, J. (March 30, 2023) For your phone and EV, a cobalt supply chain to a hell on earth. Yale E360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/siddharth-kara-cobalt-mining-labor-congo