OLEAD210:

Lesson 2: Theory and Maxim

Theory and Maxim

This lesson will examine theories, comparing and contrasting them with maxims. As a quick overview, theories are explanations of the world around us based on logic and observation. A maxim, on the other hand, is an explanation of the world based on personal experience. Both are used in leadership, with theories being much more reliable and useful.

Lesson Objectives

At the end of this lesson, you should be able to do the following things:

- Define and distinguish theories and maxims.

- Explain why theories are stronger than maxims.

- Explain pseudoscience.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

![]()

Theory

Theory is a word that gets used a lot in both everyday language and your academic coursework. We are going to define theory and then delineate it from its everyday use.

A theory, in short, is an explanation that is both well-reasoned and empirically supported (Pelham & Blanton, 2013). In other words, it combines two of the ways of knowing—logic and observation, which the previous lesson discussed. Theory used in this sense often refers to a scientific or discipline-specific theory. Leadership theory, for example, uses scientifically collected data to explain leadership; it can then be used to make recommendations to leaders based on strong evidence about leadership situations.

Everyday Theory

Most of us come across the word theory in everyday language, where it tends to refer to an educated guess or an unsupported prediction intended to explain a phenomenon. You will often hear phrases like "Here's my theory" or "Theoretically, what's happening is..." In both examples, with a little probing, it becomes clear that the speaker isn’t using real evidence, just their personal beliefs. This difference is very important because very few people actually recognize the difference. Which leads to very poor information because these everyday theories are not actually supported by reality. You will even see this see this problem on talk news programs. We will return to why scientific theories are better than everyday theories in more detail after we review maxims.

Maxim

An informal, everyday theory should actually be called a maxim. A maxim also explains the world but, rather than using empirical evidence, it is based on a personal belief system, experience, or guiding principle. In short, a leadership maxim is based on one leader’s success case; it may or may not apply to other situations. (We’ll revisit this a bit later in an example about Jeff Bezos.)

Theory Versus Maxim

A theory uses multiple kinds of evidence (primarily direct observations) from many different research studies to continually refine and improve its explanatory power. It's constantly upgrading its logic using facts that reflect reality. This continuous improvement eventually solidifies into something that we call true, because it has shown to be the case time and time again.

A maxim, on the other hand, is akin to one person’s opinion based on their personal set of circumstances. The “evidence” that they use to create their maxim will fit their personal biases. In other words, the information is cherry-picked to support a personal worldview. This issue is known as confirmation bias, and we will revisit it later in the course. A much stronger approach to knowing something is to be open-minded, review all information, and shift direction or your actions based on the reality that the information reflects.

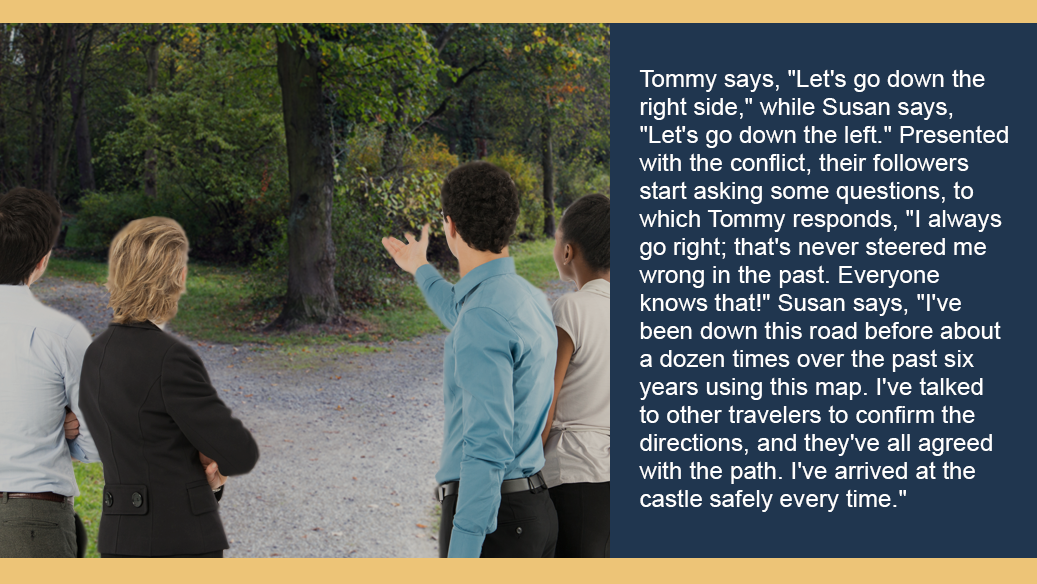

Let’s look at a very simple example of two people leading a group down a path through the woods to a castle. Tommy has never been down the path before, but is a charismatic leader who people often follow. Susan has been on the path many times, arriving at the castle every time because she's asked others about their experiences and bought a map. At one point in the journey, they come across a fork in the road. (See Figure 2.2 for what happens next.)

This is obviously a silly example, just for fun, but what you are seeing is theory (Susan and her map) versus maxim (Tommy’s beliefs about going right) in action. It happens all the time in real life, like when you see two people debating a scientific issue on television. The two sides are presented as equal, even though the scientist is usually drawing upon theories based on facts collected from hundreds or even thousands of sources. In contrast, the politician or TV personality is using either a pseudoscientific perspective or a maxim to make their case. Unfortunately, this kind of debate has reduced the dissemination of useful information into the public (Otto, 2016). That's why a course like this is so important—it will help you sort through what is useful evidence and what is not.

Why Theories and Maxims?

We’ve already mentioned why the distinction between theories and maxims is important, but it's worth elaborating upon.

Leadership is tough to make generalizations about because relevant sample sizes are small. Therefore, it can be hard to create reliable statistics in order to, through empirical support, move a theory from one way of knowing (logic) to two (combination of logic and observation). To a certain extent, maxims are unavoidable—and many current and former leaders are willing to share their experiences. That said, the lessons they impart might have issues, since certain things can never be verified via maxim. Let’s look at an example.

Everyone looks to Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon, as a great leader. And, indeed, he's led one of the largest and most profitable corporations in history. But is it because he's inherently a great leader? Or did he happen to start a company at the right time, when the public was waiting for an online retailer? Was it that the workforce he hired was, for the first time in history, technologically savvy enough for a company like Amazon to actually work? Was it the dot-com boom boosting the U.S. economy enough for it to support a company that lost $719 million in its first seven years (Hendricks, 2014)?

All of these questions can help us explain Amazon’s success, but we often attribute that success to Jeff Bezos himself because the personal leadership maxim he endorses is attractive to a public audience. It's also easier for us, as witnesses to the success, to focus on a single person rather than various situational details. We are trusting Bezos's expertise as a single individual (authority), but it is lacking full empirical support (observation), because not all of its elements can be measured in a scientific way. (Please note that we aren't knocking Jeff Bezos—by all accounts, he is a good leader. This example is only intended to show why maxims are not great for understanding the full extent of leadership, especially compared to theories, which get at all of the details.)

What happens when personal maxims are applied to organizations? Very occasionally, they actually improve the organization, but that can be attributed to chance. Typically, they have no effect. In some cases, though, they have a distinct negative effect, harming the organization with ideas that don't fit. There can be all sorts of reasons for the mismatch:

- organizational culture,

- current societal pressures,

- customer perceptions, and

- many more.

Let’s take a look at a popular example from the 1980s. Jack Welch headed General Electric, a highly profitable country that was one of the biggest in the world. Welch's personal leadership maxim was to cut the bottom 10% of employees every year. This helped drive investments into the company, as the 1980s were known for cutthroat business tactics that were popular among the general public. Later, though, the company struggled when other parts of the economy excelled (as in, for example the dot-com boom). Welch's maxim fell out of favor as GE's success decreased. There are all sorts of reasons for this, but none can ever truly be measured. It could be that good people stopped applying to the company, knowing that they might not have a job in a year. It could be the dot-com industry hiring all the talent. The list goes on and on.

Theory is a stronger way to explain leadership. Using logic and observation, theories methodically and quantifiably build solid explanations of leadership that work in nearly any situation. Theories, unlike maxims, can have a large impact on organizational leadership and performance. The theories that you have studied and will study in the OLEAD program, for example, have collected evidence from thousands of leaders using a variety of methods over an extended period of time. A large amount of observed evidence paints a more holistic picture of leadership than any maxim (a single opinion) ever can.

Think of it this way: If you were going to guess your odds for winning the lottery, which would you do?

- Base your guess on the fact that one person won the lottery last year.

- Calculate the odds based on the number of tickets sold.

A person guessing based on theory would calculate their odds based on the fact that there is a very slim chance of winning—literally one in a million. Someone acting on a maxim might base their guess on knowing someone who won, assuming success is easy.

Pseudoscience

It is not always easy to distinguish theories from maxims. Maxims are often presented in a way that makes them seem scientific.

This is part of the reason your reading for this week focuses on pseudoscience. Pseudoscience refers to personal opinions (i.e., maxims) that cherry-pick supporting information—or, at worst, actually use manufactured or falsified information as support.

As a leader, you want what's best for your organization. Pseudoscience basically attempts to get money out of your organization without any real or lasting effect. To help your organization succeed, sort through what is truly useful (theories and facts), what is unknowable (maxims), and what has no real support at all (pseudoscience). This course, among others in your Penn State career, is aimed at helping you become a better consumer of information so that you can guide your organization to success.

![]()

This lesson discussed theories and maxims, explaining why theories are more useful: They are based in two ways of knowing that support each other (logic and observations from a variety of methods over time), whereas maxims are based on a single observation at best. We also briefly examined the idea of pseudoscience and how it can make a maxim appear valid.

References

Hendricks, D. (2014, July 7). 5 successful companies that didn't make a dollar for 5 years. Retrieved from www.inc.com/drew-hendricks/5-successful-companies-that-didn-8217-t-make-a-dollar-for-5-years.html

LiteraryDevices Editors. (2018). Maxim. Retrieved from https://literarydevices.net/maxim

Otto, S. L. (2016). The war on science. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

Pelham, B. W., & Blanton, H. (2013). Conducting research in psychology: Measuring the weight of smoke. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.