Main Content

Lesson 02: The Continuous Reinventing of the Machinery of Government

Political Activities of Public Agencies

Once scholars identified the fallacies in the notion of a clear dichotomy between politics and administrations, a robust literature developed pointing out the ways that public agencies and departments "played politics." Before we examine some of the specific political activities of public agencies, it's important to introduce another rather unique element of PA in the United States: the role given to political appointees.

As a more professional approach to staffing the government emerged with the growth of PA in the Progressive Era, the traditional American fear of unelected elites and unaccountable executive power led to the retention of politically based appointments (as opposed to merit-based civil service appointments) for top positions in the federal government. In a sense, this was the logical extension of the prevailing politics/administration dichotomy philosophy. These appointees were the agents of the president to ensure that the president's agenda would be followed by the executive agencies. Never large in number, today between 2,000 and 3,000 such jobs exist. These individuals' positions range from top-level department secretaries, such as Secretary of State, to mid-level assistants, to deputy secretaries or commissioners of one of the alphabet soup of regulatory agencies, like the Federal Emergency Management Agency within the Department of Homeland Security. Appointees don't expect to have lasting tenure in office and usually don't even serve the full term of the president who appointed them. Their political activities are numerous and include testifying on policy and budget issues with committees of Congress, working with clientele groups, being the public face of the organization in speeches and in emergency situations, and coordinating the work of their particular agency with the agenda of the president. In these tasks, they may find they're also representing the shared interests of the organization in which they work or perhaps that they're on a different course than the one preferred by the permanent career professional staff.

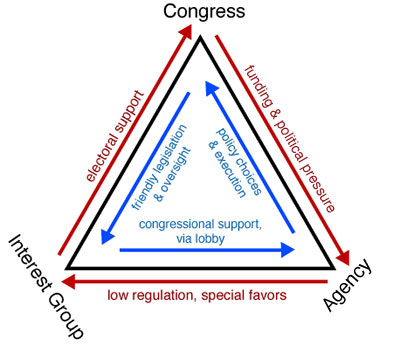

Much of the study of the political activities of the executive branch assumes that appointees are only one aspect of the political phenomenon. Scholars point out that the long-term political interests and biases of an agency and relationships with other players in the system—particularly Congress and interest and advocacy groups—are not willingly or ably bucked by short-term political appointees. This phenomenon is sometimes called pluralism, or interest group liberalism, by political scientists. It's often visualized as a triangular process of give and take between the agency, committees of Congress that are concerned with the policies and appropriations of the agency, and interest groups concerned with the product of policymaking that affect their interests. A classic example is the cozy relationships among the Army Corps of Engineers, committees of Congress (particularly the chairs and ranking members with the clout to direct projects to their districts), and interest groups, such as shippers, inland waterway operators, and governors and mayors whose jurisdictions will receive economic benefits from projects. Such projects often fall under the radar of presidents concerned with broader issues or aren't worth the political battles to challenge holders of power on committees. The notion is that the agency itself, not any particular appointee, is the unit of analysis. That is, the agency has a long-term desire to work with its allies in the process to achieve tangible goals: larger budgets, greater policy initiatives, and lessened controls by the White House.