PADM500:

Lesson 02: The Continuous Reinventing of the Machinery of Government

Lesson Overview

This lesson is designed to answer the following questions: What is the context in which issues of public administration (PA) are played out? How have we organized ourselves as a political system to make decisions on issues of public concern? What are the structures, rules, organizations, and processes of government, and how do they determine the role that PA plays?

In other words, what is the political context in which PA operates? So far, we've examined the historical context: how a continuing process of change and adaptation has led us to where we are now and where we're heading in the future. By political context, we mean not just politics in the sense of elections, political parties, campaign ads, and so on, but also the way in which we're organized as a regime. Regardless of where PA is studied, political context matters, and everyone who studies or practices PA needs a good understanding of the regime in which they operate. By regime, we mean the stable set of rules, laws, institutions, and values that exist and provide the foundation for day-to-day political and administrative activity. In the United States, the Constitution has provided the basis of a regime marked by peaceful transfer of power from one set of leaders to the next, institutional stability, and a consensus in society about the legitimacy of the state. This idea of regime exists in contrast to the more familiar context, where we talk of regime change as the sort of thing we have seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, represented by a change from a one-party dictatorship to an emerging democracy, or in the dramatic changes in Central and Eastern Europe after the breakup of the Soviet Empire.

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the basic structure of the U.S. political system, with a focus on the Constitution, the separation of powers, the different tools used by government, and the interrelationships among the branches and levels of government.

- Identify the elements of the administrative state.

- Describe the organization of the executive branch of the U.S. national government.

- Recognize and understand the role that the chief executive plays in the executive branch, with a focus on the presidency.

-

Trace the concept of government reform historically through the major commissions.

-

Point out and discuss major problems and issues in reconciling the operations of public agencies to the political environment.

Lesson Road Map

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Fundamentals of Government Organization

Let's start our lesson with a review of the fundamentals of government organization. The focus is on the national government of the United States, but we'll point out a few comparisons between the U.S. system and other approaches as we go along. What is most essential to know about the U.S. political system? For many of you, especially those who have studied political science, this discussion will be very basic and obvious. However, for others who haven't studied our system or who aren't that familiar with American practice, it should be helpful.

Let's start our lesson with a review of the fundamentals of government organization. The focus is on the national government of the United States, but we'll point out a few comparisons between the U.S. system and other approaches as we go along. What is most essential to know about the U.S. political system? For many of you, especially those who have studied political science, this discussion will be very basic and obvious. However, for others who haven't studied our system or who aren't that familiar with American practice, it should be helpful.

All discussion of the political environment of PA in the United States has to start with the Constitution. Formed in the decade after the end of the Revolutionary War in the 1780s, it established a system of government that's still fundamentally the same as it was in the early years of the republic. Changes through amendment have been relatively few. The major elements of the Constitution are as follows:

The Administrative State

The Constitution was developed at a time when developing a system of administration and providing goods and services to the public through public action was less of an issue than it became in later periods. Thus, the Constitution is largely silent on issues of administrative organization and process, other than specifying that Congress has the power to create (and by implication, remove) administrative bodies by regular legislation (no constitutional amendments required) subject to approval or veto by the president in that person's role as chief executive.

Franklin Roosevelt

The result was a small and limited federal executive branch until the rise of PA in the period between the 1880s and the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933–1945). It wasn't until the Roosevelt presidency that the United States created what scholars such as Richard Stillman call the "administrative state." This term implies a political/administrative system characterized by large public bureaucracies providing a range of public programs, some regulating private behavior and others providing direct services, such as unemployment insurance, road construction and maintenance, and so on. The administrative state in the United States was slow in coming compared to most other modern nations. As Stillman points out, most European nations went in the opposite direction in reconciling democracy and administration: Their administrative states were established as monarchical systems that were later democratized, whereas the United States started as a virtually "stateless" system with minimal administrative capacity that gradually reconciled democracy with a large state apparatus.

When we speak of the administrative state, we mean the following:

- A great deal of society's problems are assigned to public bureaucracies, and many of society's resources flow through public bureaucracies.

- Much of the political dynamics in the system revolve around the control and direction of public policies administered by public bureaucracies.

- An elaborate system of rules, laws, and delegated powers is needed to coordinate the various elements of the state and ensure it's controlled by political elites in the three constitutional branches of government.

The Executive Branch

Figure 2.1. The Government of the United States (click the image to download)

Figure 2.1. The Government of the United States (click the image to download)

Most of the work associated with PA takes place in the executive branch of government. The roles of any executive branch of government tend to fall into two major categories: faithfully administering laws handed down from the legislature and responding to emergencies and crises. See Figure 2.1 to learn about different branches of the U.S. government.

The term executive branch in the U.S. national government implies a coherence and overall philosophy of organization that is definitely not present in reality. The federal executive branch is a complex web of different sorts of organizations based on separate legislation and organized without any general template. This structure mirrors successful organizations found in the private sector. However, a few basic patterns are apparent.

The Historical Account of the Growth of the Executive Branch

The reading by Newcomer and Kee provides a good historical account of the growth of the executive branch since the founding of the republic in the 1780s and 1790s. Federalist 23, one of the most significant of the essays that form the Federalist Papers, provided a theoretical justification for a strong national government with an active and competent system of national public administration as a key factor. Yet, as the authors point out the enormous growth in the role played by the national government in the economy and society could not have been anticipated at the time that Hamilton, Madison, and Jay made their arguments for a strong national government.

What has occurred, according to Newcomer and Kee, is the expansion of responsibility without the necessary capacity to provide the sort of leadership that only the national government can provide in a system of divided powers and complex public–private relationships. The size of the national government workforce has been kept artificially low for political reasons, leading to a complex way of doing business that requires policies to be administered by subnational governments or private contractors, or through the use of fiscal policy and other indirect means. The authors propose the need for an overall strategic design led by the national executive to provide the "unity of energy" Hamilton thought was the essential role of the executive. This idea can be accomplished through attention to accountability mechanisms for contracting and intergovernmental relations, attention to risk management concerns, and strategic workforce planning.

Reforming the National Machinery of Government

The 20th century witnessed a number of major reform committees and commissions that scrutinized government machinery:

- The Brownlow Committee: Government grew rapidly and haphazardly during the New Deal. To help the president manage his assignments, the Brownlow Committee substantially increased the size of the presidential staff in 1936.

- Hoover Commissions: Hoover Commissions were set up following World War II in an attempt to reorganize the federal government.

The contemporary debate over privatizing government might be traced back to the second Hoover Commission report of 1955. Privatization may refer to the selling of governmental assets, the private finance of public facilities, or the private provision of services. Advocates of privatization, in large measure, point to the potential payoff in efficiency and productivity. Opponents note that privatization is not trouble-free and may lead to abuse and misuse. At a minimum, privatization raises special concerns when it comes to the military (e.g., problems with private security firms in Iraq); increasing pressures on the nonprofit sector to provide federally mandated public services; and faith-based initiatives—using religious organizations to provide social services—which raise questions about the appropriate separation between church and state. In large measure, voluntarism and philanthropy have been institutionalized and bureaucratized, leading full circle to the kinds of problems that critics of public provision frequently point to in justifying third-sector, charitable, or nonprofit provision of public services.

- The Ash Council: During President Nixon’s term of office, this council called for a major restructuring of cabinet agencies.

- The President’s Private Sector Survey on Cost Control (PPSSCC) also known as the Grace Commission: Undertaken during the Reagan administration, this commission produced a report that was extremely detailed and not very useful.

Reinventing Government

By 1980, the tax revolt movement in 38 states forced the government to reduce or stabilize tax rates. Then the Reagan revolution came along, with its slogan, “Government is the problem.” The deficiencies apparent in government were taken up again in the 1990s with the “reinventing government” movement and its reports, such as the National Performance Review (also known as the Gore Report), which spoke of the mushrooming national debt, the enormous waste in government, the diminution of public trust etc.

The Chief Executive

Surprisingly to those of us who have grown up assuming a large White House organization was the original intention, the idea of a well-staffed chief executive organization is a relatively recent phenomenon dating from the late 1930s and the Franklin Roosevelt presidency. Roosevelt inherited a presidency with virtually no staff and budget; the White House was mostly a dwelling place, not the combination home and office it is today. As the administrative state grew by leaps and bounds in the 1930s, Roosevelt found he had almost no capacity to coordinate the operations of the growing executive branch. (This was not made easier by the highly pragmatic and political way the executive branch was expanding, with little attention to organizing new programs and agencies around some logical plan.) He relied on friends, relatives, a few top appointees requisitioned from departments to fulfill White House duties. Knowing he had a problem, he enlisted a group of top scholars in PA to come up with a plan. Called the Brownlow Committee after its chairman, Louis Brownlow, and staffed by experts in the field, the committee began its report with the words "the president needs help." Its plan was to emulate the organization of successful large corporations to provide the chief executive with adequate staff, both a personal staff that could be assigned work on an ad hoc basis and staff units, such as the Bureau of the Budget (then part of the Treasury Department and only in existence since the 1920s), to provide ongoing assistance in managing the work of the executive branch.

As has been the case generally for PA, war and economic emergency have been the drivers of change in White House organization. During World War II, Roosevelt found it difficult to require cooperation and coordination between the military services fighting the war. (The navy, led by Admiral Ernest King, was especially problematic, in Roosevelt's opinion.) After Roosevelt's death and the end of the war, the Department of Defense was created to provide a single department to coordinate the work of the different services, along with the National Security Council within the Executive Office of the President (also called the EOP, the term given to those staff units that report directly to the president). Other efforts to create coordinating units within the EOP, such as the Domestic Council and the Office of Policy Development, have had mixed success.

Each president has a wide range of options in organizing the White House staff in ways that fit their leadership and management approach. Many choose to have a strong chief of staff—in essence a deputy president—to control all staff operations and "guard the door" to the president. None have chosen to follow the so-called cabinet approach of convening all the heads of the cabinet-level units around a table to hammer out collective decisions. Ronald Reagan used a unique "troika" arrangement in his first term, with three top staffers sharing what in other presidencies would be the chief of staff role; it worked for him because the three individuals, Edwin Meese, James Baker, and Michael Deaver, put aside their personal agendas to serve the president loyally. In the George W. Bush administration, the chief of staff approach was employed but Vice President Richard Cheney assembled his own staff and functioned as a de facto deputy president, especially in the first years of the administration.

Regardless of how they organize the White House, all modern presidents have learned that controlling and directing the departments and agencies of the administrative state is a difficult, tiresome, yet essential aspect of the office.

Political Activities of Public Agencies

Once scholars identified the fallacies in the notion of a clear dichotomy between politics and administrations, a robust literature developed pointing out the ways that public agencies and departments "played politics." Before we examine some of the specific political activities of public agencies, it's important to introduce another rather unique element of PA in the United States: the role given to political appointees.

As a more professional approach to staffing the government emerged with the growth of PA in the Progressive Era, the traditional American fear of unelected elites and unaccountable executive power led to the retention of politically based appointments (as opposed to merit-based civil service appointments) for top positions in the federal government. In a sense, this was the logical extension of the prevailing politics/administration dichotomy philosophy. These appointees were the agents of the president to ensure that the president's agenda would be followed by the executive agencies. Never large in number, today between 2,000 and 3,000 such jobs exist. These individuals' positions range from top-level department secretaries, such as Secretary of State, to mid-level assistants, to deputy secretaries or commissioners of one of the alphabet soup of regulatory agencies, like the Federal Emergency Management Agency within the Department of Homeland Security. Appointees don't expect to have lasting tenure in office and usually don't even serve the full term of the president who appointed them. Their political activities are numerous and include testifying on policy and budget issues with committees of Congress, working with clientele groups, being the public face of the organization in speeches and in emergency situations, and coordinating the work of their particular agency with the agenda of the president. In these tasks, they may find they're also representing the shared interests of the organization in which they work or perhaps that they're on a different course than the one preferred by the permanent career professional staff.

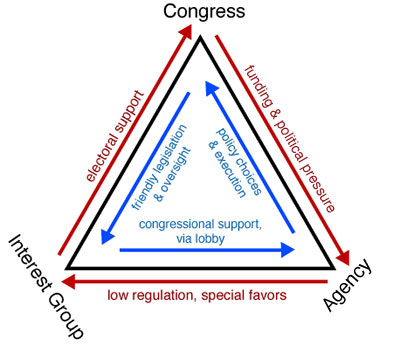

Much of the study of the political activities of the executive branch assumes that appointees are only one aspect of the political phenomenon. Scholars point out that the long-term political interests and biases of an agency and relationships with other players in the system—particularly Congress and interest and advocacy groups—are not willingly or ably bucked by short-term political appointees. This phenomenon is sometimes called pluralism, or interest group liberalism, by political scientists. It's often visualized as a triangular process of give and take between the agency, committees of Congress that are concerned with the policies and appropriations of the agency, and interest groups concerned with the product of policymaking that affect their interests. A classic example is the cozy relationships among the Army Corps of Engineers, committees of Congress (particularly the chairs and ranking members with the clout to direct projects to their districts), and interest groups, such as shippers, inland waterway operators, and governors and mayors whose jurisdictions will receive economic benefits from projects. Such projects often fall under the radar of presidents concerned with broader issues or aren't worth the political battles to challenge holders of power on committees. The notion is that the agency itself, not any particular appointee, is the unit of analysis. That is, the agency has a long-term desire to work with its allies in the process to achieve tangible goals: larger budgets, greater policy initiatives, and lessened controls by the White House.

Contemporary Problems and Issues

The limited success of the Bush and Obama management programs illustrates the obstacles in the path of those who wish to reform the system of PA in the United States. Reform efforts often seem to embrace romantic notions of returning government to the simpler days of the Founding Fathers, or unrealistic comparisons between managing in the private sector and the much more complex world of PA. The elephant in the room is the lack of trust and understanding of many citizens regarding the nature of public management.

Operating in a political system of divided powers (hence, from the standpoint of the public manager, one of divided ownership and accountability) and asked to balance demands for efficiency and flexibility with equally important demands for responsiveness and accountability, managers, whether politically appointed or from the career ranks, face enormous challenges in making programs work.

- The image of PA in the minds of many, if not most, is that of a collection of self-interested, faceless bureaucrats. In fact, it's often a paradoxical image: On the one hand, bureaucrats are seen as aggressive, power-hungry tyrants, and the on the other timid, rule-embracing, risk-avoiding factotums.

- The image of the bureaucrat coincides with the image of big government, constantly expanding its role in society and the costs of maintaining it.

- With the rise of new public management (NPM) and its continuing influence, allocating responsibilities to the proper organization to implement policies is much more complex than before, with a myriad of networks, contracts, and other connecting devices in use, with the public manager and organization ultimately responsible for results.

- The growth of NPM and networks linking public and private organizations has raised the issue of what values need to be operationalized: public sector values stressing responsiveness and collaboration with the citizenry, or private sector values associated with bottom-line results.

- The political environment in which PA must operate is one in which organized interests—lobby groups, advocacy groups, the media, contractors—hold great sway, both in direct dealings with public agencies and with the political institutions that hold them accountable.