PADM502:

Lesson 2: Principles of Public Finance - The Role of Government

Lesson Overview

The subject area of public finance lies in the intersection between economics and politics and provides important theoretical justifications for public sector involvement in the economy. These justifications explain why it might be in a society’s best interest for the public sector to engage in certain economic activities, including but not limited to providing public goods and services. The goal of this lesson is to introduce those principles of public finance that are most relevant to fiscal decision making.

Lesson Objectives

Before beginning this lesson, think about the following lesson objectives. After completing this lesson, you should be able to

- describe and exemplify what types of economic activities the public sector ought to be involved in (from a public finance perspective);

- describe the theoretical justifications for public sector involvement in these activities;

- apply basic economic efficiency criteria as a way to determine if the provision of a particular good or service will enhance economic welfare; and

- list reasons and exemplify why decisions about the use and acquisition of public resources might at times be suboptimal.

Lesson Roadmap

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Key Questions to Organize and Guide Your Study

Here are several key questions to guide your learning about the principles of public fiance. Think about these questions as you read the material:

- How does public finance differ from private finance?

- Why might it not be in a society’s best interest to rely on the private sector to provide all goods and services in an economy?

- When is it in a society’s best interest to have governments provide particular goods and services?

- Why might decisions about the acquisition and use of public resources be suboptimal?

- Why does the lack of market feedback complicate the provision of public goods and services?

Publicly Funded Activities

Publicly funded activities affect almost all facets of our lives. We attend public universities, send our kids to public schools...the examples are almost endless.

Publicly funded activities affect almost all facets of our lives. We attend public universities, send our kids to public schools, drive on public roads, visit public hospitals, rely on public health and pension coverage, etc. The examples are almost endless.

The provision of these and other goods and services by governments implies two things: first, that the goods or services provided are needed, and second, that the public sector will do a better job of providing them than the private sector would. A continuous challenge, however, is that there often is no readily available feedback to shed light on whether these assumptions are reasonable or not.

If the services mentioned above were provided in private sector settings, these questions would typically be resolved by people "voting with their wallets." That is, consumers would provide feedback to private sector entities by paying for only those goods and services they need or want. If goods and services are priced too high or fail to meet people's wants or needs, then they will not be purchased in sufficient quantities and will eventually disappear from the marketplace unless necessary market-driven adjustments occur (e.g., reinvention of the products, lowering of prices, or improvement in the quality of the products).

In public sector settings, however, governments often do not have the luxury of receiving such feedback. An important reason for this is that most government produced goods and services are not paid for by the same people that benefit from them. Rather, they are typically funded by means of general taxes or other revenues that are not directly linked to consumption. This "broken" link between those who benefit from public goods and services and those who pay for them represents a fundamental difference between government finance (i.e., public finance) and private finance. One example that illustrates this broken link is the funding of public schools. These are typically financed by local property taxes. People who own property are required to pay local property taxes, regardless of whether their children attend the school system (e.g., they may be homeschooled).

The subject of public finance provides us with an important starting point for understanding what types of economic activities the public sector ought to be involved in. Or more specifically, it provides us with some basic principles that can be used to guide choices about the use and acquisition of public resources in the absence of a normal market test. Most important, it outlines the theory of market failure, which offers insight into why it might not be in the best interest for a society to rely solely on the private sector to provide goods and services. These market failures are described in Chapter 1 of the Mikesell text and will be discussed on the next page.

Consider: Before moving on to the next page, try to identify some basic public services that are provided by a local government in your area. How are these financed? Are they financed by the same individuals who will benefit from them, or is the link between use and finance "broken"? (Note: These questions are intended to help you think about how the above issues relate to a real-world context; you do not need to submit anything.)

Theories of Market Failure

The theories of market failure provide a theoretical justification for government intervention and the role of government in the economy.

The theory of market failure can briefly be described as a set of economic theories that seek to explain why free markets sometimes fail to allocate goods and services in a way that maximizes a society's welfare. Or, worded differently, they seek to explain why individuals' pursuits of pure self-interest sometimes result in a situation where a society's limited resources could have been used better.

Economists are often concerned with the causes of market failures and possible means to correct such failures when they occur. As indicated on the previous page, a possible corrective measure is to rely on the public sector to rectify these failures. Toward this end, the theories of market failure provide a theoretical justification for government intervention and the role of government in the economy.

Government Intervention in the Economy According to Musgrave

On the remainder of this page, we will review the role that the public sector ought to have in the economy, according to Richard A. Musgrave (1910-2007). Musgrave is significant for the purposes of this lesson because of the important role he played in shaping modern public finance. In fact, he is referred to by many as the father of modern public finance. He earned this title, largely as a result of his book The Theory of Public Finance (1959), which provided the first English-language, comprehensive account of public finance. In this book he outlines three basic types of economic activities in which government intervention can be justified based on the theories of market failure. These economic activities are

- allocation of resources,

- distribution of goods and services, and

- economic stabilization.

To familiarize yourself further with Musgrave, read the assigned article, "Richard A. Musgrave, 96, Theoretician of Public Finance, Dies," written by Walsh and published in the New York Times. (Note: You can also access the article via the library e-reserves.) It provides a general overview of Musgrave’s contributions to public finance. A more detailed description of the three types of economic activities listed above is provided in Chapter 1 of the Mikesell textbook. As you read this chapter, try to imagine additional examples of public sector activities (beyond those provided in the textbook) in each of the three functional areas mentioned.

Six Failures

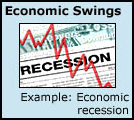

As you read Chapter 1 in the Mikesell book, you will find that the chapter provides a more detailed account of how the existence of various market failures can be used to justify government involvement in the above three functional areas. In essence, the article proposed that free markets, when left to their own devices, fail to allocate goods and services efficiently due to one of six types of failures. These failures are illustrated in Figure 2.1: Six Failures.

As you will find when reading the Mikesell text, these six failures give rise to a range of problems that governments are expected to correct.

While these problems are exemplified and described in more detail in the textbook, they are briefly described as follows (you can navigate each failure by clicking the circle or arrow icon):

Economic Efficiency Criteria

The previous description of market failures provides some general insights into why it might not be wise to rely entirely on the private sector to provide goods and services in an economy. However, it is important to realize that a decision to involve the public sector in the provision of a particular good or service does not necessarily mean that society will be better-off. For example, it is possible to conceive of a situation in which the construction of a public road or bridge will result in costs to society that far exceed the benefits the project will generate.

The previous description of market failures provides some general insights into why it might not be wise to rely entirely on the private sector to provide goods and services in an economy. However, it is important to realize that a decision to involve the public sector in the provision of a particular good or service does not necessarily mean that society will be better-off. For example, it is possible to conceive of a situation in which the construction of a public road or bridge will result in costs to society that far exceed the benefits the project will generate.

This would be the case if a decision was made to build a bridge or a road that no one ends up using. Consequently, it is important to know not only whether a good or service ought to be provided by the public sector, but also whether it makes sense from an economic perspective to provide it. On this page we introduce two additional public finance concepts that shed light on the latter question (i.e., whether the provision of a particular type of public good or service will enhance economic welfare): Pareto efficiency criterion, and Kaldor-Hicks efficiency criterion

As indicated by their names, these concepts relate to economic efficiency. Briefly described, economic efficiency deals with how well a society economizes with (i.e., uses) its limited resources. Formally, economic efficiency is achieved when a society's resources are used or allocated in a way so that there is no other possible way for a society to use them better.

The second criterion, the Kaldor-Hicks efficiency criterion, named for economists Nicholas Kaldor and John Hicks, captures some of the intuitive appeal of the Pareto efficiency criterion, but is applicable to more circumstances. It states that a good or a service should be provided if a Pareto optimal outcome can be reached by arranging sufficient compensation from those who are made better-off to those who are made worse-off. In this manner, everyone would end up no worse-off than before. More simply put, a good or service should be provided as long as the total (aggregate) benefits of the project outweigh the total costs. If this is the case, the provision of the good or service will increase societal welfare and society as a whole will be better off.

A major challenge associated with the Pareto and the Kaldor-Hicks criteria is that they both assume that it is possible to assess the value that individuals in a community place on a particular project, public good, or service that is being considered. In the absence of market prices, assessing the value that different people place on a particular good or service is very difficult. Nevertheless, economists and analysts often attempt to estimate these values so that they can determine the total benefits (i.e., the aggregate benefits for all individuals in a community) that will result from producing a particular public good or service. As will be discussed in Lesson 6, they do this by applying a variety of techniques aimed at determining the perceived benefits to each individual and then expressing them in dollar terms. The aggregate value of all the individual perceived benefits are then compared with the aggregate costs. If the benefits exceed the costs, the Kaldor-Hicks criterion is met.

A simple illustration of the Kaldor-Hicks criteria would be if 10 individuals who live on a particular street decide to invest in a street light. Let's say that each of five of the individuals perceives the value (i.e., what they are willing to contribute in dollars) of the light to be $500. That is, they would be willing to pay $500 each for this good if it were sold on the private market. Furthermore, let's say that four of the individuals perceive the value to be $400, and the remaining individual perceives it to be $100. In this example, the Kaldor-Hicks criterion would be met as long as the total cost of the street light were less than $4,200, which is the total value of the perceived benefits: ($500 x 5) + ($400 x 4) + ($100 x 1). For example, if the cost were $3,200, the net benefit to society would be $1,000.

Review Exercise: Efficiency Criteria

Review Exercise: Efficiency Criteria

The review exercise below provides an additional illustration of the above criteria. Try to answer the questions before you click to retrieve the correct answers.

A planned community project (a public good) will cost $2,500 to produce. It has been determined that it will be financed by a one-time fee of $500 that is evenly distributed across the community members. If undertaken, the project will benefit the five members of the community as follows:

| Resident | Individual Benefit | Cost Share |

|---|---|---|

| A | $800 | $500 |

| B | $800 | $500 |

| C | $300 | $500 |

| D | $350 | $500 |

| E | $450 | $500 |

Kaldor-Hicks: Ethical Dilemma

As noted above, the Kaldor-Hicks criterion is more easily applied to practical circumstances. However, an obvious drawback to the Kaldor-Hicks efficiency criterion is that someone might be left worse-off if public resources were allocated or used in a particular way. As such, it gives rise to a range of possible ethical and moral dilemmas. An illustration of this is provided in the required Robert Caro (1998) article (you may download this article from the Library Reserves). The article describes some of the ethical and moral trade-offs that occurred when Robert Moses designed and implemented the New York City park and transportation system.

- What groups of people appear to have been made worse-off in the case described?

- Under what circumstances (if any) is it justifiable to provide a particular good or service that will increase the overall well-being of an economic region, but harm a few?

From Theory to Practice: On Suboptimal Decisions

Thus far, this lesson has centered on the basic principles of public finance that offer theoretical insights into when and how public sector involvement might result in economic efficiency improvements (i.e., decisions that contribute positively to the economic welfare enjoyed in society). It should not surprise you, however, that in practice collective decision making about how to allocate or use public resources does not always result in efficiency improvements. As indicated in the textbook, this discord can partly be attributed to the institutional decision-making framework. A case in point is the use of referendums. Depending on the voters' preferences, a majority vote referendum might reject a decision that would have enhanced economic welfare if undertaken. This can be illustrated by looking at the data presented in the previous review exercise. Again, the data is as the same as in Table 2.1.

A community project (a public good) will cost $2,500 and will benefit the five members of the community as follows:

| Resident | Individual Benefit | Cost Share |

|---|---|---|

| A | $800 | $500 |

| B | $800 | $500 |

| C | $300 | $500 |

| D | $350 | $500 |

| E | $450 | $500 |

As noted earlier, this project would generate a net improvement of $200 to the overall economic welfare. Hence, from an economic welfare perspective it should be undertaken. However, since the cost for each of residents C, D, and E is higher than their perceived individual benefits, they would likely vote against it. Thus, the three "no" votes would turn down this project (i.e., a 2 to 3 vote) and the opportunity to improve the overall economic welfare in the community.

Use of Representative Government

The assumption that elected officials operate in the best interest of their constituents is also a highly contested assumption.

In this course we will largely ignore the use of referendums as a decision-making framework and focus instead on the traditional process that governs fiscal decision making—the use of representative government to raise funds and allocate resources. However, as you are probably aware, reliance on representative government also poses a variety of challenges unless we assume a perfect world in which (1) elected representatives are able to make decisions based on perfect knowledge, and (2) where representatives always utilize this knowledge in ways that best benefit the public (i.e., they are assumed to be "public utility maximizers").

However, as we all know, we do not live in a perfect world, and the above two assumptions rarely hold water in the real world. Elected officials rarely operate under conditions of perfect knowledge. In practice, such knowledge is often tied to individualonstituents’ unique circumstances and is therefore difficult to

capture/collect. Some refer to this unique type of knowledge as private knowledge. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for the information upon which elected officials base their decisions to be biased in favor of a particular decision.

The assumption that elected officials operate in the best interests of their constituents is also a highly contested assumption. Political processes are often characterized by logrolling and political bargaining. As we move through this class, these and other assumptions will be emphasized for purposes of illustrating the complexity of the budget process.

On the next page you will be given an opportunity to delve into and reflect on these difficulties in more detail. Specifically, you will be required to read and reflect on a classic article that explores the practical challenges involved in capturing and using knowledge as a basis of decision making.

Hayek's "The Use of Knowledge in Society"

Decisions aimed at effectively allocating limited resources (a task that government is charged with) require knowledge that no individual or group of experts has or is capable of acquiring.

This lesson's academic article sheds light on the role and use of knowledge in decision making and is directly related to the discussion on the previous page. It was written by the Austrian economist Friedrich A. Hayek (1899–1992). Hayek received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 1974 with Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal and is known for his defense of free-market capitalism against socialist and collectivist thought. He is considered by many to be one of the most important economists and political philosophers of the twentieth century. He spent most of his academic career at the London School of Economics and at the University of Chicago.

As mentioned above, the assigned article was selected because of the important insights it offers into the use of knowledge in decision making. Specifically, the article emphasizes that decisions aimed at effectively allocating limited resources (a task that government is charged with) require knowledge that no individual or group of experts has or is capable of acquiring. As such, the article sheds light on the complexities of authorizing representatives to make centralized decisions on behalf their constituents.

As you read the article, pay particular attention to the two different types of knowledge that Hayek discusses: "scientific" and "private" knowledge (the latter is described in the article as knowledge that individuals possess separately). In addition, reflect on why it is important for a representative body to be able to capture private knowledge for purposes of making decisions about the use and acquisition of public resources. Finally, consider why it might be difficult for a representative body to capture such knowledge.

If you would like to learn more about F.A. Hayek and his writings, I recommend that you listen to the following podcast (please note that you are not required to listed to this podcast) published by the Library of Economics and Liberty:

- Boudreaux on Reading Hayek (Note: The conversation was recorded on December 7, 2012. The length of the entire recording is 1:13:02.)

The podcast includes an interview with Don Boudreaux of George Mason University, who is interviewed by Russ Roberts, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The podcast provides an overview of Hayek's most important writings and suggestions on how to approach Hayek's works if you are a beginner. If you do not have enough time to listen to the entire podcast, you may want to listen to the initial 30 minutes, which provides a more general overview of Hayek's writings.

References

Hayek, F. A. (1945, September). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519-530.

1. Externalities

1. Externalities  2. Failure to Provide Public Goods

2. Failure to Provide Public Goods  3. Failure of Competition

3. Failure of Competition  4. Information Asymmetry

4. Information Asymmetry  5. Inequities

5. Inequities  6. Economic Swings

6. Economic Swings