PADM503:

Lesson 2: Protection of Human Subjects and Other Ethical Issues

Lesson Overview

Research plays an important part in generating and advancing knowledge about issues that affect various aspects of human life. Conducting research is an exciting activity, but it comes with responsibilities. This need for responsibility is particularly true for the research that involves human beings as participants. Research participants can provide very useful information, some of which could be personal or professional in nature.

It is the researcher’s duty to conduct the inquiry in a responsible manner that does not put participants at physical, psychological, or professional risk. You might ask: How can I put participants at risk if I am conducting research on administration or policy? Well, the information provided in this lesson will answer your question!

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson you should be able to

- recognize the importance of ethical practice when conducting research projects;

- identify and evaluate the potential risks for human participants in a research project;

- discuss the principles of ethical treatment of human subjects, including informed consent;

- discuss the federal rules and regulations for protecting human participants, including the roles and functions of the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs);

- demonstrate knowledge of the rules of the Office for Research Protections (ORP) at Penn State; and

- apply your knowledge of protecting employees and clients as research participants when you apply for permission to conduct a study in your organization.

Lesson Roadmap

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Note: It is very important that you complete the textbook chapter readings before you study the topics in this lesson. The information in this lesson is not meant to replicate what is in the book. The information and the examples provided here are based on the assumption that you have read the chapter.

Protecting Human Participants

Background

A series of unethical research practices with regards to human subjects led to the creation of the current rules.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972)

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972)

- Conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service on 400 African American men with syphilis.

- They were intentionally misinformed, treatment was never administered, and the men were never given adequate treatment for their disease.

- Optional: See the Centers for Disease Control website for its history and more information: http://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

- The Nazi war crimes that were revealed at the Nuremberg trials (1945–1946)

- Medical experiments were conducted on thousands of prisoners without their consent that resulted in disfigurement, permanent disability, or death.

- Many physicians who conducted the experiments were found guilty at the Nuremberg Trials.

- The Willowbrook Study (1963–1966)

- Conducted at the New York institution for mentally handicapped children.

- Children were deliberately infected with hepatitis virus to test vaccines.

In response to these unethical practices and others, the following rules were developed.

These rules cumulatively determined the way research in social and biological (medical) sciences are conducted today. The most recent and comprehensive of these cumulative rules is the “Common Rule” of the U.S. Federal Government (see details at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/common-rule/index.html).

The following table summarizes the overall development of the rules in a chronological order.

| Rule | Year | Content |

|---|---|---|

| The Nuremberg Code | 1947 | Ten principles of ethical research were adopted. |

| The Declaration of Helsinki | 1964 | Principles adopted: Minimize risks, obtain informed consent, and protect personal integrity of participants. |

| The National Research Act | 1974 | Codified the principles for protecting human participants, created IRB. |

| The Belmont Report | 1979 | Formulated the three current principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. |

| The Federal Common Rule | 1991 | Required IRB reviews for all federally funded research projects; most comprehensive principles to this date |

Table 2.1. Ethical Rule Development

Note: Read the O’Sullivan et al., book and Michelle Stickler, The Ethics of Human Participant Research (PSU ORP Slides), for more details.

In this lesson we will talk about The Belmont Report and the Federal Common Rule of 1991 in detail as they are more relevant for social science and public administration research.

The Belmont Report Principle #1: Respect for Persons

There are two issues to consider under this principle:

- Informed Consent

- Protecting Privacy and Confidentiality

Informed consent

Give as much information as might be needed to make an informed decision about participating in the research.

Participants should be informed about

- the general purpose of the study;

- possible risks (known and unknown), i.e., discomfort, anxiety, career risks, loss of privacy, embarrassment, inconvenience, etc.;

- probable benefits;

- why they were selected (it must be an equitable distribution where the sample should not be too large);

- what will be done with the collected information; and

- the voluntary nature of participation.

Remember that when acquiring informed consent, the researcher should not be in a position to influence the subject. Think about teacher-student relations as an example:

When the teacher asks for the consent of students to participate in a research study on which classes they like the best in a program, he or she should not force them to participate in the study. Nor should the teacher should try to influence the responses. It is possible that the teacher could influence the students due to his or her position, so the teacher should request someone else to administer the survey, and the student responses should be anonymous with no identifying information on the survey. This way, the students (respondents) will be assured that the teacher will not be able to link their responses with their identify.

Note that the federal laws allow exemptions of informed consent for large surveys, like nationwide and statewide surveys. However, Penn State rules do not allow this exemption.

How to develop an informed consent form

Keep in mind the following points when developing the consent form to protect the human participants of the study.

- All wording must be at an 8th grade reading level or below.

- In the form, you should clearly declare and/or include

- purpose of the study;

- procedures to be followed;

- discomforts or risk;

- statement that participants may withdraw their participation at any time;

- statement that participants can decline to answer specific questions; and

- information about how confidential information will be kept as such.

See the PSU ORP website for additional information about informed consent: Research at Penn State

Protecting Privacy and Confidentiality

Protecting privacy and confidentiality is integral to the Belmont Principle#1: Respect for Persons.

This need is an issue spelled out in federal regulations as well. According to the Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there are three kinds of risks for harming research participants: physical, psychological, and informational. Typically, when you conduct a research study in public administration, public policy, health administration, or a similar field, participants would not be harmed physically. It is more likely to harm them by releasing their personal information. They may also be harmed psychologically. The following quote from an FDA document explains the three ways people may be harmed:

Most research risks to the individual can be categorized into one of three types: physical, psychological, and informational risks. (Although there are other harms, such as legal, social, and economic harms, these can usually be viewed as variations on those core categories.) Physical risks are the most straightforward to understand—they are characterized by short term or long term damage to the body such as pain, bruising, infection, worsening current disease states, long-term symptoms, or even death. Psychological risks can include unintentional anxiety and stress including feelings of sadness or even depression, feelings of betrayal, and exacerbation of underlying psychiatric conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological risks are not necessarily restricted to psychiatric or social and behavioral research.

Informational risks derive from inappropriate use or disclosure of information, which could be harmful to the study subjects or groups. For instance, disclosure of illegal behavior, substance abuse, or chronic illness might jeopardize current or future employment, or cause emotional or social harm. In general, informational risks are correlated with the nature of the information and the degree of identifiability of the information. The majority of unauthorized disclosures of identifiable health information from investigators occur due to inadequate data security. (Source: Federal Register.gov)

Confidentiality and Anonymity

There are two key concepts in understanding the issues in protecting information about research participants: confidentiality and anonymity. You need to clearly understand the difference between confidentiality and anonymity. Confidentiality is an issue when the researcher knows who the participant is, but decides to keep this information undisclosed to protect the participant’s privacy. In the case of anonymity, the researcher does not know who the respondent is; so the researcher cannot possibly make any link between the information collected and the individual who provided the information.

Think about this example: A researcher mails a survey questionnaire to 100 individuals. To keep her data organized she assigned a unique number to each individual survey questionnaire. She made a note of each questionnaire’s serial number and its corresponding address and the individual’s name in a data file. In this case, when a survey is returned to the researcher, she will be able to link the identity of the individual and the responses to the questions. For example: Survey #005 is back. The database shows that Survey #005 was sent to John Doe.

Think about this example: A researcher mails a survey questionnaire to 100 individuals. To keep her data organized she assigned a unique number to each individual survey questionnaire. She made a note of each questionnaire’s serial number and its corresponding address and the individual’s name in a data file. In this case, when a survey is returned to the researcher, she will be able to link the identity of the individual and the responses to the questions. For example: Survey #005 is back. The database shows that Survey #005 was sent to John Doe.

Confidentiality is relevant in this case. Why? Because the researcher knows the participant’s identity, and she can reveal it to others (for example, to the public) if she wants to. Her obligation, according to basic research rules is to keep it confidential to protect the participant.

Think about an alternative scenario. No unique survey number is linked to any participant’s address or name. In that situation, there is no way the researcher would know who sent the survey questionnaires back and who did not. Among the questionnaires that are returned, she cannot identify who sent back which one. She cannot reveal the identity of the respondents or what each respondent said, even if she wants to. In this case, the results are anonymous.

The mantra for most researchers is that anonymity is preferred (in terms of protecting research participants), but it may not be possible. Think about a research project in which the researcher interviews participant face-to-face. Then, it is impossible to maintain anonymity as the researcher knows who is being interviewed.

The mantra for most researchers is that anonymity is preferred (in terms of protecting research participants), but it may not be possible. Think about a research project in which the researcher interviews participant face-to-face. Then, it is impossible to maintain anonymity as the researcher knows who is being interviewed.

Confidentiality is a more important concept in the previous example than anonymity, because confidentiality is more applicable. When considering how to ensure confidentiality in your research project, think carefully about all possible ways personal information may be released, intentionally or unintentionally. For example, think about the possibility of deductive disclosure. The question is this:

Could information about a participant be unintentionally linked to his/her identity?

Think about this scenario: In your research report, you mention that a 21-year-old blonde male who is the single son of his single-parent mother in Community X told you that he had used illegal substances. There is only one “21-year-old blonde male who is the single son of his single-parent mother in Community X.” You did not reveal his name, but someone who knows the community can identify that person and this identification may potentially harm the participant. You should think about possibilities like this one and take all possible precautions to protect the confidentialities of research participants.

Note that the federal laws do not necessarily make a researcher’s job easy. Many of the federal laws about confidentiality and privacy are equivocal. They want you to protect the privacy of respondents, but the rules may be contradictory. For example:

- Research records can be subpoenaed by courts. Thus private information will be revealed at least to the judge and jury members.

- Market researchers are allowed to disclose individual information. They can sell the addresses and telephone numbers they have. This is why you keep receiving unsolicited mail and telephone calls from advertisers.

In July 2011, The U.S. Food and Drug Administration proposed new guidelines for "Enhancing Protections for Research Subjects and Reducing Burden, Delay, and Ambiguity for Investigators". It is yet to be seen to what extent these news guidelines will reduce the contradictions and clarify the rules.

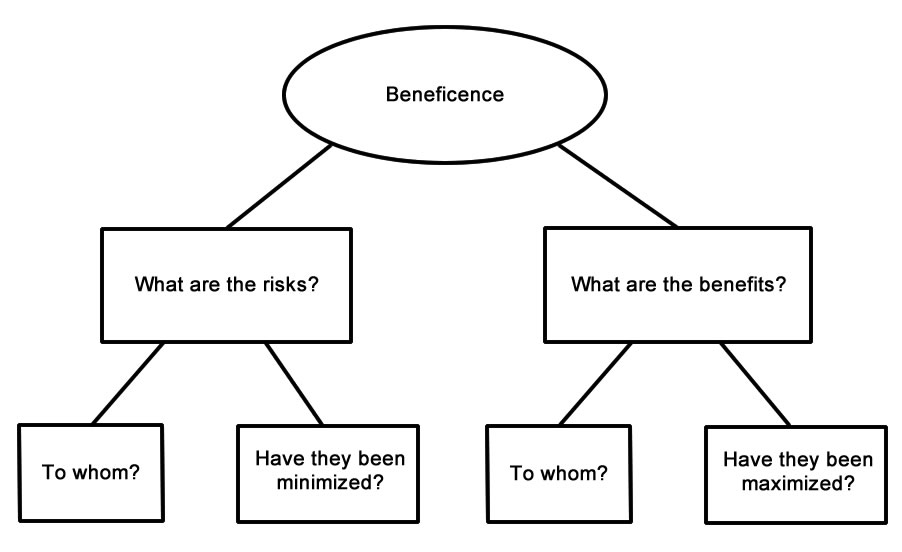

The Belmont Report Principle #2: Beneficence

The beneficence principle is about the benefits and risks of the research project for participants.

Figure 2.1. Information to Be Included in an Informed Consent Form

An informed consent form should include the information in the above chart: Participants should be made aware of any risks and benefits of the study.

Consider the following factors when designing your research.

- Would the survey cause high-level stress because of questionnaire contents?

- Would participants experience anxiety, as some questions might bring back past memories or remind them of issues that are sources of anxiety for them?

- Could participation in the study cause delusions or have other psychological effects?

- Could any of the questions be perceived as an invasion of privacy? Is deception necessary in the study? In some studies it is necessary, but avoid it if it is not really necessary.

If there are potential problems like the ones above, you should think about the following:

- How to minimize them.

- How to compensate for them. (Paying participants for their participation may be an option.)

The Belmont Report Principle #3: Justice

The third Belmont principle is justice. This principle is important to keep in mind when selecting a sample for the study. Selection of research participants should be unbiased and fair. It should be taken into account who may benefit from the study. The researcher should make sure not to exclude a certain group from the study to deprive them of certain benefits.

Think about medical tests. If you are testing a new drug that can potentially cure a life-threatening disease, you will have to select a sample for your test and exclude others. Then you should not discriminate against a particular group of individuals intentionally. For example, samples should not be intentionally selected from an underdeveloped third world country for the ease of the experiments because these countries might not have human subject protection regulations that researchers need to adhere to.

Keep the following questions in mind when making an ethical sample selection.

- Does recruitment for the study target the population that will benefit from the research?

- Does the recruitment unfairly target a population?

- Are the inclusion/exclusion criteria fair?

Institutional Review Boards

The establishment of institutional review boards (IRBs) is required by the Federal Common Rule of 1991 (see the information at U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). Researchers must have their research projects reviewed for ethical conduct and procedural appropriateness by the IRBs. A research project can begin only after the IRB approval is granted. Violation of the Common Rule may result in the termination of federal funding to the researcher, and even to the researcher's institution.

IRB’s check

- risks;

- selection of subjects;

- informed consent documents;

- appropriate measures for safety of subjects; and

- provisions for confidentiality.

Typically, IRBs conduct three different kinds of review:

- Human Research Participant Program (HRPP): experts review applications to determine if they really are exempt.

- Expedited: Reviewed by a member of IRB.

- Full: Reviewed by the full Institutional Review Board.

For more information on the types of review and the processes check this website: Research at Penn State. Go to the “Types of Review” sections to know more about the different kinds of reviews.

Ethics in Research

This section is mainly concerned with the ethics relevant to the process of data collection, presenting the findings, and giving due credit to those who deserve it. To ensure that the research is ethically conducted, researchers should focus on

- research integrity;

- integrity in disseminating research findings; and

- giving credit to those who deserve it.

The following discussion addresses all of the above concerns in more detail.

The potential issues that could compromise the ethical research conduct are

- trimming;

- cooking;

- forging;

- plagiarism; and

- not recognizing contributions and authorship.

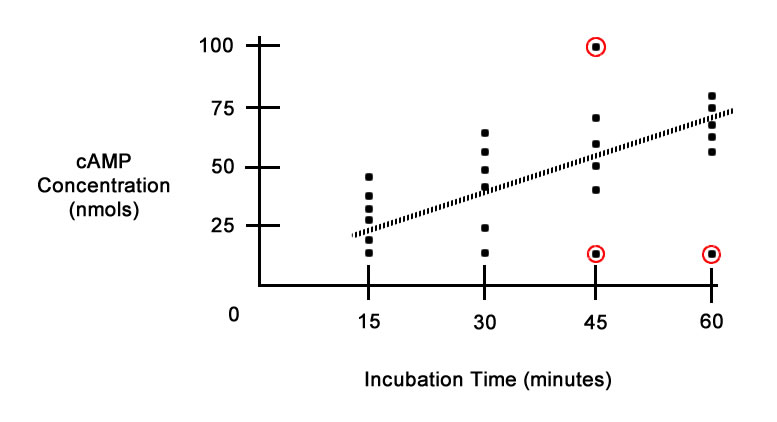

Trimming

Definition: The smoothing of irregularities to make the data look extremely accurate and precise.

Example (from Vrana slides):

Trimming irregular data in a scatter plot to make the pattern look smooth:

A student prepares a “scatter graph” that demonstrates the time dependent effect. Unfortunately, several points do not follow the relationship.

Peers suggest dropping the lowest point because “the cells were obviously dead” and the highest point because it is an “outlier.”

This change would be considered trimming irregular data in a scatter plot to make the pattern look smooth. See the circled dots in the chart below; these are the "outliers.”

Chart 2.1. Trimming Example Scatter Graph

Chart 2.1. Trimming Example Scatter Graph

Deleting the outliers will strengthen the relationship that the researcher reports. For more understanding about the outliers and the strength of the relationship, wait until the discussion of scatter plots later in this course. For now, this example indicates that the data has been trimmed to show stronger correlation.

Cooking

Definition: “[R]etaining only those results that fit the theory and discarding others.”

Example: Discarding experimental results that do not fit the researcher’s hypothesis and keeping only those that fit.

Forging

Definition: “[I]nventing some or all of the research data that are reported and even reporting experiments to obtain data that were never performed.”

Example: Making up data that were never found in an experiment. Suppose a researcher was collecting information for a study about how sleep affected employees' performance. Rather than asking the employees about how many hours they slept, the researcher decided to make up a dataset without performing data collection. This is called forging.

Authorship

Definition: “Authorship on a scientific paper should be limited to those individuals who have contributed directly to the design and execution of the experiments and who have participated in the preparation of the manuscript.”

Example: In a co-authored project, the authors are listed based on their level of contribution. When there is equal contribution, they are mentioned alphabetically. This is a general practice; however, the authorship should be discussed and agreed upon among the collaborators before publication of the report.

Giving Credit

Definition: “Attribution of credit involves the acknowledgements of individuals who have contributed time, money, or materials to a scientific endeavor.”

Plagiarism

Definition: “Plagiarism is the misappropriation of another individual’s thoughts, ideas, or writings and claiming them as one’s own.”

You should particularly understand the definitions of the following terms (Penn State’s definitions):

Plagiarism: The fabrication of information and citations; submitting others' work from professional journals, books, articles, papers, electronic sources of any kind, or the submission of any products from commercial research paper providers regardless of what rationales a vendor uses; submission of other students' papers or lab results or project reports and representing the work as one's own; fabricating, in part or total, submissions and citing them falsely. Note: Copying and pasting any materials from the World Wide Web is plagiarism.

Acts of Aiding and Abetting: Facilitating acts by others; unauthorized collaboration of work; permitting another to copy from an exam; permitting another to copy from a computer program; writing a paper for another; inappropriately collaborating on homework assignments or exams without permission or when prohibited, etc.

Submitting Previous Work: Submitting a paper, case study, lab report, or any assignment that had been submitted for credit in a prior or concurrent class without the knowledge and permission of the instructor(s).

Failure to Cite Electronic Resources Regardless of the Source: All electronic resources must be cited in every report, paper, project, portfolio, or any other document submitted for evaluation by an instructor.

Examples of Plagiarism:

- Submitting someone else’s class paper as if it were your own.

- Paraphrasing someone else's ideas in your own words, without acknowledging the original source.

- Allowing others (e.g., your classmates) to give you too much advice in writing a class paper. (What is “too much”?)

- Mosaic plagiarism (see the Department of English Plagiarism Policy below).

Penn State has strict policies to prevent plagiarism. One of the best descriptions of plagiarism and methods of preventing it are at the Department of English website. The following is copied from the department’s website. Read carefully and apply the principles in your writing!

Penn State Department of English Plagiarism Policy (copied from Penn State English Department)

The Department of English insists on strict standards of academic honesty in all courses. Therefore, plagiarism, the act of passing off someone else's words or ideas as your own, will be penalized severely. The following discussion is offered so that you won't commit plagiarism.

Sometimes plagiarism is simple dishonesty. If you buy, borrow, or steal an essay to turn in as your own work, you are plagiarizing. If you copy word-for-word or change a word here and there while copying without enclosing the copied passage in quotation marks and identifying the author, you are also plagiarizing.

But plagiarism can be more complicated in act and intent.

Paraphrasing, stating someone else's ideas in your own words, can lead you to unintentional plagiarism. Jotting down notes and ideas from sources and then using them without proper attributions to the authors or titles in introductory phrases may result in a paper that is only a blend of your words combined with the words of others that appear to be yours.

Another way to plagiarize is to allow other students or friends to give you too much rhetorical help or do too much editing and proofreading of your work. If you think you have received substantial help in any way from people whose names will not appear as authors of the paper, you should acknowledge that help in a short sentence at the end of the paper or in your list of Works Cited. If you are not sure how much help is too much, talk with your instructor, so the two of you can decide what kind of outside help (and how much) is acceptable, and how to give credit where credit is due.

As you go through the writing process, you should keep careful track of when you use ideas and/or exact words from sources. As a conscientious writer, you have to make an honest effort to distinguish between your own ideas, those of others, and what might be considered common knowledge. Try to identify which part of your work comes from an identifiable source and then document the use of that source using the proper format, such as a parenthetical citation and a Works Cited list. If you are unsure about what needs documenting, talk with your instructor.

When thinking about plagiarism, it is hard to avoid talking about ideas as if they were objects like tables and chairs. Obviously, that's not the case. You should not feel that you are under pressure to invent completely new ideas. Instead, original writing consists of thinking through ideas and expressing them in your own way. The result may not be entirely new, but, if honestly done, it may be interesting and worthwhile reading. Print or electronic sources, as well as other people, may add useful ideas to your own thoughts. When they do so in identifiable and specific ways, give them the credit they deserve.

The following examples should clarify the difference between dishonest and proper uses of sources.

The US has only lost approximately 30 percent of its original forest area, most of this in the nineteenth century. The loss has not been higher mainly because population pressure has never been as great there as in Europe. The doubling of US farmland from 1880 to 1920 happened almost without affecting the total forest area as most was converted from grasslands.

From Bjorn Lomborg, The Skeptical Environmentalist

Word-for-Word Plagiarism

In the following example, the writer tacks on a new opening part of the first sentence in the hope that the reader won't notice that the rest of the paragraph is simply copied from the source. The plagiarized words are italicized.

Despite the outcry from environmentalist groups like Earth First! and the Sierra Club, it is important to note that the US has only lost approximately 30 percent of its original forest area, most of this in the nineteenth century. The loss has not been higher mainly because population pressure has never been as great here as in Europe. The doubling of US farmland from 1880 to 1920 happened almost without affecting the total forest area as most was converted from grasslands.

Quotation marks around all the copied text, followed by a parenthetical citation, would avoid plagiarism in this case. But even if that were done, a reader might wonder why so much was quoted from Lomborg in the first place. Beyond that, a reader might wonder why you chose to use a quote here instead of paraphrase this passage, which as a whole is not very quotable, especially with the odd reference to Europe. Using exact quotes should be reserved for situations where the original author has stated the idea in a better way than any paraphrase you might come up with. In the above case, the information could be summed up and simply paraphrased, with a proper citation, because the idea, even in your words, belongs to someone else. Furthermore, a paper consisting largely of quoted passages and little original writing would be relatively worthless.

Plagiarizing by Paraphrase

In the following case, the exact ideas in the source are followed very closely—too closely—simply by substituting your own words and sentences for those of the original.

| Original | Paraphrase |

|---|---|

|

The US has only lost approximately 30 percent of its forest area, most of this in the nineteenth century. |

Only 30 percent of the original forest area has been lost. |

|

The loss has not been higher mainly because population pressure has never been as great there as in Europe. |

Europe has fared slightly worse due to greater population pressure. |

|

The doubling of US farmland from 1880 to 1920 happened almost without affecting the total forest area as most was converted from grasslands. |

Even though US farmland doubled from 1880 to 1920, little forest area was affected since the farms appeared on grasslands. |

The ideas in the right column appear to be original. Obviously, they are just Lomborg's ideas presented in different words without any acknowledgement. Plagiarism can be avoided easily here by introducing the paraphrased section with an attribution to Lomborg and then following up with a parenthetical citation. Such an introduction is underlined here:

Bjorn Lomborg points out that despite environmentalists' outcries. . . . (page number).

Properly used, paraphrase is a valuable rhetorical technique. You should use it to simplify or summarize so that others' ideas or information, properly attributed in the introduction and documented in a parenthetical citation, may be woven into the pattern of your own ideas. You should not use paraphrase simply to avoid quotation; you should use it to express another's important ideas in your own words when those ideas are not expressed in a way that is useful to quote directly.

Mosaic Plagiarism

This is a more sophisticated kind of plagiarism wherein phrases and terms are lifted from the source and sprinkled in among your own prose. Words and phrases lifted verbatim or with only slight changes are italicized:

Environmentalist groups have long bemoaned the loss of US forests, particularly in this age of population growth and urbanization. Yet, the US has only lost approximately 30 percent of its original forest area, and most of this in the nineteenth century. There are a few main reasons for this. First, population pressure has never been as great in this country as in Europe. Second, the explosion of US farmland, when it doubled from 1880 to 1920, happened almost without affecting the total forest area as most was converted from grasslands.

Mosaic plagiarism may be caused by sloppy notetaking, but it always looks thoroughly dishonest and intentional and will be judged as such. In the above example, just adding an introduction and a parenthetical citation will not solve the plagiarism problem since no quotation marks are used where required. But adding them would raise the question of why those short phrases and basic statements of fact and opinion are worth quoting word for word. The best solution is to paraphrase everything: rewrite the plagiarized parts in your own words, introduce the passage properly, and add a parenthetical citation.

Summary

Using quotation marks around someone else's words avoids the charge of plagiarism, but when overdone, makes for a patchwork paper with little flow to it. When most of what you want to say comes from a single source, either quote directly or paraphrase. In both cases, introduce your borrowed words or ideas by attributing them to the author and then follow them with a parenthetical citation.

The secret of using sources productively is to make them work for you to support and amplify your ideas. If you find, as you work at paraphrasing, quoting, and citing, that you are only pasting sources together with a few of your own words and ideas thrown in-that too much of your paper comes from your sources and not enough from your own mind-then go back and start over. Try rewriting the paper without looking at your sources, just using your own ideas; after you have completed a draft entirely of your own, add the specific words and ideas from your sources to support what you want to say.

If you have any doubts about the way you are using sources, talk to your instructor as soon as you can.

Lesson Summary

There is a long history of the violations of human rights by researchers. Over time, principles and rules were formulated to prevent such violations from happening. These principles and rules led cumulatively to the creation of the current rules by the U.S. federal government (“Common Rule”) in 1991. These rules regulate researchers' conduct to make sure that research participants’ rights are respected, they are informed about the goals and procedures of research projects, the benefits and costs of a research project are distributed fairly, and research participants are selected fairly.

In brief, when conducting a research project, ask five questions before you start collecting your data:

- Is there harm to participants?

- Are they sufficiently informed and their consent for participation obtained?

- Is their privacy invaded?

- Is there deception involved in the research project? If so, is it justified?

- Are research participants selected based on scientific principles? Are there any fairness issues in selecting them?

There are other ethical issues a researcher should be concerned about when conducting a study. The following ethical questions should be asked.

Have you conducted the study ethically, keeping the following issues in mind?

- Trimming

- Cooking

- Forging

- Plagiarism

- Recognizing contributions and authorship

Plagiarism is a particularly important issue. Have you taken enough precautions to make sure that in your presentation of the results of your study (e.g., writing a paper) none of the following has occurred?

- Word-for-Word Plagiarizing

- Plagiarizing by Paraphrase

- Mosaic Plagiarism

Lesson 2 Activities

CITI Training

- Take the CITI training courses (as explained Lesson 1).

- Save your completion reports from CITI that you receive at the end of the courses and submit them to the CITI Drop Box.

- E-mail a copy of each completion report.

SPSS Tutorials

Continue working through the SPSS tutorials at Lynda.com. These tutorials must be completed by the end of Lesson 4.