PADM507:

Lesson 2 : The Policy Making System, History and Structure of Policy Making in the United States

Lesson 2 Overview

Lesson 1 discussed a foundation of public policy and policy process by defining public policy, clarifying the concepts of public policy, and describing the key attributes of public policy, the role of politics in policy making, and social scientific disciplines that study public policy. These offer basic understanding of how policies are made and implemented.

Lesson 2 explores the stages model of the policy process and the elements of the policy-making system, the historical development of policy making, and the structure of public policy making in the United States. The stages model is an essential key reference point for public policy studies.

The policy process is considered as a system, so it is critical to identify important elements of environments, inputs, and outputs. After reviewing a wide range of environmental factors that influence public policy making, we move to discuss the constitutional order in which policymaking takes place in the United States. You need to know the structure of government and policymaking to make sense of the policy process itself.

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to

- describe the stages model and the system model of policy,

- describe key components of the policy system,

- classify the elemets of the constitutional policymaking order in the United States, and

- describe the impact factors (e.g., American ideology) on producing stability in the American constitutional system.

Lesson Road Map

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Stages Model

We briefly mentioned in the previous lesson that the policy process can be described as sequential stages in which a public policy is made. This way of understanding the policy process is known as the “stages model.”

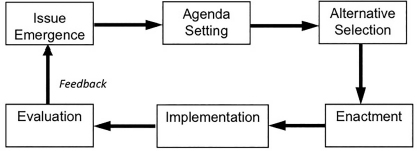

The stages model, introduced by Lasswell (1956), is one of the two earliest models that is still used in public policy studies and policy analysis. Originally the stages model was described by Lasswell in seven stages. Later, some scholars combined or divided the original stages model, and proposed variations of the model. Bikalnd (2020), the author of the course textbook, proposed the following variation of the model (see Figure 2.1).

The stages model assumes that the policy process is relatively stable, ordered, and open. The subsequent models discussed here are responses to the stages model, either attempts to expand it in more analytic detail or critiques of its basic approach and assumptions.

First, a word about each stage in the model (later lessons will examine the nature of each stage in more detail):

- The first step is issue emergence. This stage is important to consider, because a standard view is that policy discussion would not begin unless there was a problem identified as appropriate for the government to address and substantial enough to warrant action.

- The second stage is agenda-setting. This approach focuses on how certain problems get on the government agenda for discussion and occasionally on solutions being considered.

- Alternative selection is the stage at which specific solutions are developed, debated, and researched.

- Enactment is the point at which decision-makers formally decide to adopt a particular policy.

- Once a policy is approved, it normally does not automatically go into operation. The program must be put into effect (the implementation phase). This might call for training employees, constructing facilities, purchasing technology, and so on.

- Once a program has been in effect for an appropriate length of time, it should be evaluated. Here, the goal is to see what the effects of the program are (whether or not it is "solving" the problem) and to see if there are any unanticipated consequences (good or bad). Based on the evaluation, changes to or termination of the program may be considered.

The stages model is a good conceptual tool because it provides a systematic policy process (Lasswell, 1971). But it should be used with some caution.

The stages should not be regarded as independent of each other. Each stage has an impact on the others. Stages can overlap (e.g. implementation and evaluation). It also suggests that there is an orderly progresion from one stage to the next, but in real-life policy processes, stages can be skipped and/or they may be done out of order.

Also, the stages model implies that there is a beginning and an end in a policy process, but the process is actually endless cycle.

References

Birkland, Birkland, T. A. (2020). An Introduction to the Policy Process (5th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Lasswell, H. D. (1956). The decision process: Seven categories of functional analysis. College Park, MD: Bureau of Governmental Research of University of Maryland, College Park.

Lasswell, H. D. (1971). A Pre-View of Policy Sciences. New York: Elsevier Publishing Company.

Public Policy System

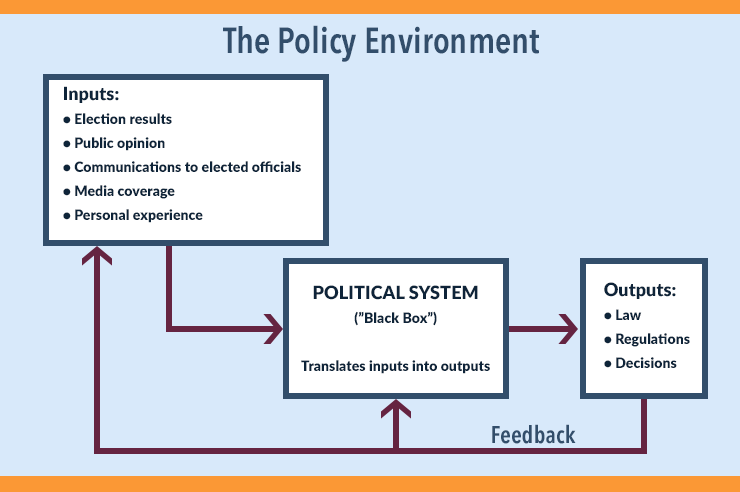

In addition to the policy stages model, another model was proposed by Easton (1965). He proposed that we should think the policy process as a system. He theorized that they key components of this system were:

- the environment in which the policy is made;

- inputs into the policy system;

- the "black box" in which the decisions actually get made;

- the outputs, or products of the decision-making process; and

- feedback, in which outputs' observable results are evaluated and used to improve or terminate programs if they are failing.

Figure 2.2 illustrates Easton's model. We summarize the elements of enviornment, input, and outputs in the following sections. More information can be found in the Birkland book (2020).

What is the Policy Environment?

According to Easton (1965), four environments influence policy making: structural, social, economic, and political environments.

The formal structural environments include the framework of the US government including the separation of powers and federalism as well as other traditions and legal structures in place that establish the rules of policymaking.

The social environment involves nature and composition of the population and society that will influence policy. For example, the United States is experiencing a growth in the 65+ age group and among the oldest citizens (ages 85 and older). This demographic trend is more pronounced in some other countries. Nonetheless, there are implications for decision-making. As the number of elderly citizens increases—even if not explosively—greater demand will be placed on such programs as Social Security and Medicare. Decision-makers in the policy system will need to respond to this trend in some way.

The political environment is about how the public feels about various issues and how will that impact the ability to set and enact policy. Policy makers use public opinion polling to assess their political and policy options.

The economic environment includes the growth of the economy, the distribution of wealth in a society, the size and composition of industry sectors, the rate of growth of the economy, inflation and the cost of labor and raw materials. Aspects of the economic environment gain the greatest attention from policy makers and the public.

What Are the Inputs?

The inputs are public demands made upon the political system and the supports of the system itself. Public opinion is one input. A key question is the extent to which public opinion can affect decision-making. Over time, there has been much research on this subject. Publications appearing in the 1980s and 1990s (and even earlier) suggest that public opinion can affect actual policy decisions. Pages and Shapiro's (1983) study illustrates how public opinions can affect public polices.

Page's and Shapiro's Study on Public Opinion (1983)

Page and Shapiro (1983) conducted a study (using results gathered over a lengthy period of time) that examined public opinion polling, which spoke to people's policy preferences. They then developed measures of policy change enacted by various governmental agents.

We see that if public opinion moves by 6%–7%, then the direction of actual policy change is not much affected. Let's say that support for increased spending on schools increased by 6% over a five-year period. If that was the case and government policy changed, 53% of the time it was in the direction of public opinion (congruent)—but it was not congruent with the increased support 47% of the time. In other words, there wasn't that much of an effect on government policy toward education.

On the other hand, if public opinion changed by 20%–29% (say, in favor of a more muscular defense policy), 86% of the time the government policy changed along with the public's mood change. This, of course, suggests that public opinion is serving as an input in the decision-making process.

| Size of opinion change | Direction of policy change: Congruent | Direction of policy change: Non-congruent |

|---|---|---|

| 6%–7% | 53% | 47% |

| 8%–9% | 64% | 36% |

| 10%–14% | 62% | 38% |

| 15%–19% | 69% | 31% |

| 20%–29% | 86% | 14% |

| 30%+ | 100% | 0% |

What Are Outputs?

The political system’s outputs are basic statements of public policy that reflect the government's intent to do something. Outputs are the results of the demands and supports. Outputs are conceptualized in a concrete form that can be easily measured.

Outputs can range from spending money to criminalizing behavior. Laws, regulations, and public services are outputs. For example, services provided by the government in regulating everything from commercial aviation to nuclear power plants are outputs.

References

Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Gilens, M., & Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of American politics. Perspectives on Politics, 12, 564–581.

Page, B. I., & Shapiro, R. Y. (1983). Effects of public opinion on policy. American Political Science Review, 77, 175–190.

The American Constitutional Order

A few words about constitutions: They can be written, as is the United States Constitution, or not (as with the British constitution). Some constitutions, including those of some American states, go into great detail; others are relatively general and brief. The American national Constitution fits the latter description.

To understand the constitutional order, you first must know what is in the American Constitution. (For the text of the Constitution, please go to the Constitution of the United States page of the United States Senate website.)

The first order of business in understanding the Constitution is simply to lay out the various articles and what they say. Do look at the greater detail in the Constitution itself, as the following is just a very basic outline of the contents.

Article I

Article I defines the structure and powers of the House of Representatives and the Senate (collectively known as Congress). The Senate is made up of two senators for each state, no matter how large or small a population it has; this provides equal representation. The House of Representatives allots representatives by a state's population. A small state (in terms of population) will have only one member in the House; more populated states will have more representatives.

Section 7 of Article I states that revenue bills will originate in the House of Representatives; more powers, including the power to levy taxes; borrow money; regulate commerce with other countries, among the states, and with Native Americans; and declare war, are outlined in Section 8. Finally, Clause 18, known as the elastic clause or necessary and proper clause, states that Congress has the power "to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof" (U.S. Const., art. I, §8).

Watch Video 2.1. The Elastic Clause Explained in 3 Minutes

KEITH HUGHES: Hey. What's up guys. Welcome to Hip Hughes History. I was just talking to a kid, and I asked the kid what the Elastic Clause was, and he said it means Congress can do anything it wants that's necessary and proper. And I said, doh, you are wrong. Everybody out there, we need to understand the Elastic Clause if you're going to understand federalism in the least. So let's start really quick with a definition. And if you know who I am, you know I do this all the time.

Federalism is the division of power between the Federal Government and the states. And how we define that is with the US Constitution. So basically, the state power rests in the 10th Amendment. And the 10th Amendment, Reserved Powers states that anything that's not in the Constitution, that's not given to the Federal Government to do is reserved for the states, which means that the Federal Government gets its power from the Constitution.

So when we look at the constitutional and we look for governmental power, federal power, it's really all over. But its biggest concentration is in Article 1, Section 8. This is called Delegated Power. Article 1 is legislative and Article 8 is a list of Delegated Power We can start with some really big ones. For instance, it says to provide for the common defense and promote the general welfare. It gives the government the ability to coin money and collect taxes. It gives the government the ability to regulate trade between the states in commerce and to promote the useful arts, and there's kind of military stuff in there.

And then we get to the Elastic Clause. So if you're going to learn anything, know the 10th Amendment and know Article 1, Section 8, clause 18. It's the last one in Delegated Powers. And we could put it up on the wall.

KEITH HUGHES (READING IN DEEP VOICE): To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the forgoing Powers and all other Powers vested this Constitution and the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

KEITH HUGHES: So if the Federal Government is going to do it, and it's not specifically in the language of the Constitution, is it constitutional? Can we do that? Yeah. If we can rationalize that what we are doing is to execute one of those Delegated Powers. So if you're an original intentionalist, you're looking at those words very carefully, and you want, really, a direct line between the law being passed and the actual words, and maybe even what you think the founders meant as intentionalism. And you're really going to limit the Federal Government. And that's definitely a legitimate ideology.

On the other side of the coin, we have language in the Delegated Powers that's a little broad to promote the general welfare, to regulate the commerce between the states. So that type of language has been used with the Elastic Clause next to it to do some things that aren't directly in the Constitution. The National Bank was created because the government has the power, according to the Constitution, to borrow money, to establish credit. And Hamilton argued that the Elastic Clause gave the government that corresponding power to create a national bank to execute that foregoing power.

[CHIME]

So you decide. You decide whether you want to be somebody who is expansionary, and that's at the expense of the 10th Amendment, perhaps, or somebody who is maybe quite limiting in the Federal Government's power, you are in love with the 10th Amendment. And that might maybe hamper the government's ability to solve a very legitimate problem. But you get to decide. Because we live in America.

All right, there you go. The Elastic Clause, Article 1, section 8, clause 18. Make sure you watch other lectures and you know where attention goes, energy flows. We'll see you next time on the YouTube's.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Articles II and III

Article II speaks of executive power, focusing most directly on the role of the U.S. president. The president's authority is not spelled out in detail; Section 1 says simply that "the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States. . ." (U.S. Const. art II, §1). Section 2 spells the powers out a bit more—the president is considered the Commander in Chief of the military, can pardon those who commit offenses against the United States, and can appoint ambassadors and federal judges (with Senate consent).

Article III gives the Supreme Court of the United States foremost judicial power; other lower federal courts have authority as Congress establishes. The article also describes the types of cases that these federal courts can hear and decide upon (their jurisdiction).

Articles IV–VII

Article IV focuses on each state's interests, such as full faith. A decision made in one state court should be respected by other state courts to prevent forum shopping, in which those who lose a case in one state seek a better judgment in another. Citizens in one state have the same privileges as citizens in a different state (such as the ability to travel freely). Section V outlines how the Constitution can be amended.

Article VI includes the supremacy clause, which states, "This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, shall be the supreme Law of the Land. . ." (U.S. Const., art. VI). Finally, Article VII describes how the Constitution is to be ratified and empowered to become the law of the land.

Amendments

Over time, 27 amendments have been added to the Constitution; the first ten, enacted shortly after the Constitution was ratified, are known as The Bill of Rights. You might want to take a look at these now; they're included in the online version of the Constitution.

References

U.S. Const. art. I, §8.

U.S. Const. art II, §1.

U.S. Const. art VI.

Key Elements in the Constitutional Order

Two aspects of the constitutional order are especially relevant to the policymaking process: federalism and the separation of powers (accompanied by checks and balances).

Federalism

Federalism refers to the division of powers across levels of government (usually focusing on the interactions between the federal government and the states). The Constitution itself notes one key component of federalism—the supremacy of national laws and the Constitution over state laws and constitutions. Over time, federalism has evolved considerably. Interested students might read Chapter 3 of the Deil Wright's Understanding Intergovernmental Relations (1988) to get a sense of the change over time.

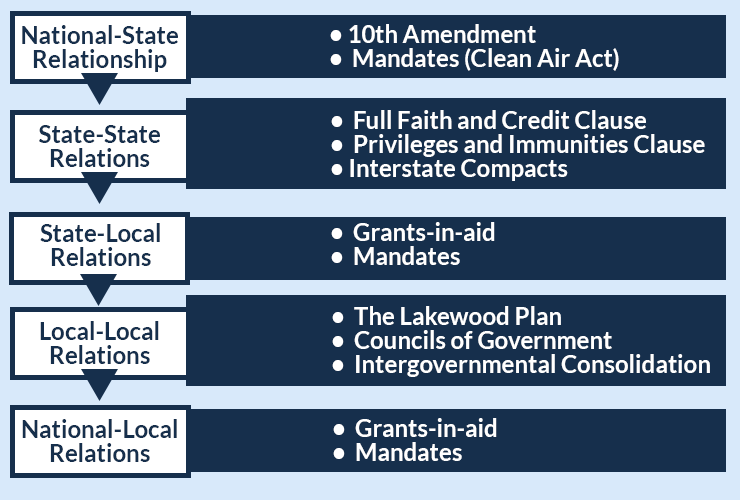

Intergovernmental relations (IGR) is a more complete view of the interactions among levels of government.

Figure 2.3 illustrates the ways in which levels of government can interact with one another. Please check different types of relationships for details via the following tabs.

National–State Relations

The national government and the state governments interact in a number of ways. The 10th Amendment lays out the states' powers (known as "reserved" powers) and the people's powers, which include powers neither granted to the federal government nor prohibited to the state governments.

Another mechanism of interaction is the mandate, in which the federal government tells a state government what it has to do (based on the supremacy clause of the Constitution). For instance, the national government can pass a law requiring states to make sure that all eligible voters can vote (this was done with the 1965 Voting Rights Act). In many southern states, obstacles were erected to make it more difficult for African-Americans to vote. The Voting Rights Act essentially told those states to cease that practice.

Other interactions come from national grants, funds made available to states to carry out projects deemed appropriate by the national government.

State–State Relations

The IGR system also includes state-level interactions. The Constitution specifies full faith and credit, as well as privileges and immunities, as discussed earlier. States can also form compacts (agreements) with one another to address mutually agreed-upon issues, as with the Connecticut River Valley Flood Control Commission (formed by Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont).

State–Local Relations

States have relationships with their local governments—those of counties, cities, or villages. States have grant programs that make funding available to local governments to serve state needs. For example, the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department makes available over $4 million annually to communities throughout the state for outdoor recreation projects. The funding for the grants comes from state lottery money (OREGON.GOV, 2015). And, of course, states may enact mandates for lower-level governmental entities. One example comes from Minnesota: If a county participates in the community corrections act, the county attorney must establish a pretrial diversion program for adult offenders designed to achieve five goals specified in the statute (State of Minnesota, 2015).

Local–Local Relations

Local governments can develop relationships to advance their interests. For instance, the Lakewood Plan (named after a community in California) features cities contracting with the county government to provide various services, from law enforcement to planning activities.

Another local–local interaction can be seen in councils of government, in which a number of municipalities join an organization designed to coordinate actions and work collaboratively on issues of common interest.

A dramatic form of local–local relations is intergovernmental consolidation. We see this occurring when Davidson County, Tennessee and its largest city, Nashville, combined into one governmental entity, currently known as the "Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County" or "Metro Nashville."

National–Local Relations

Finally, the national government interacts with local governments in a number of ways, including making grants available for them or imposing mandates on them.

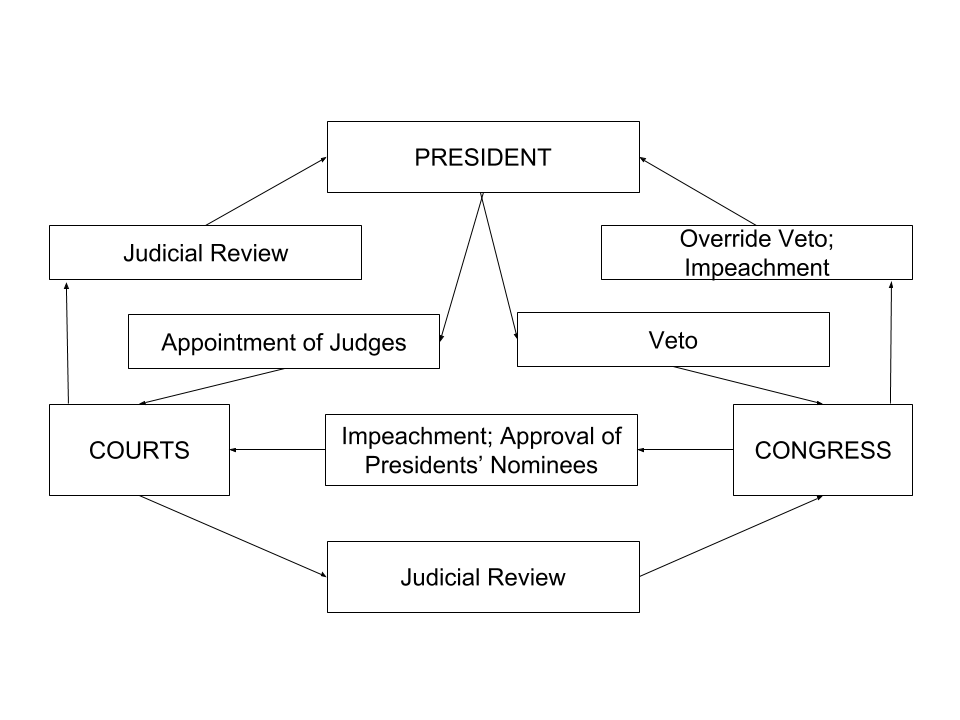

Another critical aspect of the American constitutional order is the separation of powers and checks and balances. Take a look at Figure 2.4, which illustrates this.

Separation of Powers/Checks and Balances

Figure 2.4 is a flowchart that indicates checks and balances regarding the separation of powers among the executive, judicial and legislative branches.

Separation of powers is fairly straightforward:

- Congress has the power to enact laws (legislative power),

- the president has the power to implement and enforce laws (executive power), and

- the courts have the power to interpret laws and apply the law to specific cases (judicial power).

Each of the three branches of government has the ability to "check" the others. The courts can check the executive and legislative branches by declaring their actions or decisions unconstitutional (known as judicial review). The president can check Congress by vetoing legislation; Congress can check the president by overriding the veto. The president checks the court by nominating judges when there is a vacancy or when a new court is established. Congress has a check over the courts: it can impeach and remove judges from office and approves the president's nominees. Of course, in this manner, Congress can also check the president if it objects to his nomination(s).

Messiness in Policymaking

The constitutional order affects policymaking; another graphic should make this clear. If we combine federalism and separation of power, we get Table 2.2 below.

What does the table tell us? Above all, the policymaking process is fragmented (note the discussion on this in the textbook). Power is divided by level of government and by the different branches of government. The end result is that it is often difficult to make a policy that is likely to have the desired impact. The president, Congress, governors and their state legislators, and the executive and legislative bodies at the local level normally need to agree on actions at each level. Often there are standoffs between the executive and legislative branches, rendering decision-making a challenge. Add to this the political parties, which may be at odds when there is a divided government, with one party controlling at least one component of government and the other party at least one, too.

| Level of government/separation of power | Executive | Legislative | Judicial |

|---|---|---|---|

| National | R D | R D | R D |

| State | R D | R D | R D |

| Local | R D | R D | R D |

References

OREGON.GOV (2015). Oregan Parks and Recreation Department: Grant Programs. Retrieved from http://www.oregon.gov/oprd/grants/pages/local.aspx#Local_Government_Grant_Progra

State of Minnesota (2015). Minnesota Statutes 2015. Retrieved from https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=401.065&format=pdf

Heineman, R. A., Peterson, S. A, & Rasmussen, T. H. (1995). American Government. 2nd edition New York, NY: : McGraw-Hill.

Peterson, S. A., & Rasmussen, T. H. (1994). State and Local Politics. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Changes and Stabilities in the Constitutional Order

Chapter 3 of Birkland's textbook (2020) discusses the historical development of the constitutional order over the 200+ years of the American republic under the Constitution. Initially, American citizens felt closer to their state governments than to the federal government. Over time, however, this changed. It is very helpful to understand the changes that have taken place since the enactment of the Constitution.

Evolution of the Constitutional Order Over Time

Even though the American political system is typically stable over time, dramatic changes can and do take place—even if at a slow pace.

For a quick view of key events over time in the United States, go to the Interactive Timeline on the National Constitution Center website.

First, the Constitution itself has changed. Until the Civil War era, amendments to the Constitution (outside of the Bill of Rights) were rare and not of particularly great significance. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments changed that pattern:

- The 13th Amendment ended slavery, an institution that was the foundation of the southern economy and culture.

- Section 1 of the 14th Amendment granted freed slaves the immunities and privileges of all other American citizens, forbidding states from depriving any person "of life, liberty, or property without due process of law." Finally, no person within any state's jurisdiction could be denied "equal protection of the laws" (U.S. Const. amend. XIV, §1). These clauses were clearly intended to protect the rights of former slaves.

- The 15th Amendment closed out the three Civil War amendments by guaranteeing all citizens the right to vote, a dramatic change. Of course, these amendments did not automatically prevent freed slaves from discrimination.

Another change—discussed in the textbook and alluded to earlier—had to do with the relations between state and national government.

Many people use a "layer cake" model to describe the first government under the Constitution to the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration: the state governments and the national government operated in somewhat different spheres. The states attended to their own affairs, while the national government focused more on developing the national economy, foreign relations, and national security. However, there were some collaborations between the national and state governments. The Morrill Act, passed during the Lincoln administration, provided support for a set of state colleges (land-grant institutions), such as Penn State, Michigan State, and the like.

The next phase, in some constructions, was termed cooperative federalism (Wright, 1988) or "the marble cake," in which the state and national governments worked together to address problems. Take, for instance, grant programs: the federal government would make funds available for the states to use to address national problems, with the state being a key actor in addressing such challenges. One simple example comes from a mythical employee referred to as a "sanitarian." Wright quotes Morton Grodzins, describing this employee:

"The sanitarian is appointed by the state under merit standards established by the federal government. His base salary comes jointly from state and federal funds, the county provides him with an office and office amenities and pays a portion of his expenses, and the largest city in the county contributes to his salary and office by virtue of his appointment as a city plumbing inspector. . .But [the sanitarian] does not and cannot think of himself as acting in these various capacities. All business in the county that concerns public health and sanitation he considers his business. Paid largely from federal funds, he does not find it strange to attend meetings of the city council to give expert advice on matters ranging from rotten apples to rabies control. He is even deputized as a member of both the city and county police force" (Wright, 1988, p. 72)

That represents a considerable movement away from the layer cake.

Stability in the Constitutional Order

Over the years since the Constitution was ratified and went into effect, there has been considerable stability in the United States. Of course, this has not always been the case—the Civil War is a dramatic example. But, for the most part, there has been stability and consistency. While the constitutional order has evolved, great stability underpinned the changes.

American Ideology

One key factor has been the stability over the years in the American ideology. Citizens' basic political beliefs do not change rapidly; there is a core that only slowly changes. One study that seems to make this clear is a book by Donald Devine, The Political Culture of the United States (1972). This is a rather old volume, but it summarizes public opinion data collected over several decades and across demographic groups.

A 1968 Survey of Public Opinions

Devine draws upon 35 years' worth of public opinion surveys to explore the extent to which there is a definable and stable American political culture. He argues that poll findings suggest a "liberal" tradition, in the sense of an acceptance of principles associated with political thinkers like John Locke and James Madison. Furthermore, evidence suggests that there is widespread approval of basic views across many demographic categories. The tables below (Tables 2.3-2.5) are derived from a 1968 survey of public opinion. It is striking that basic values tend to be agreed upon by many different demographic breakdowns and across many groups. However, there are anomalies. For instance, when we explore the effect of party identification, the apolitical appear to be outliers on the issue of community trust. For the most part, though, it appears as if there is considerable acceptance of certain basic values.

| Social group | Community trust (%) | Obey unjust government (%) | Responsive government (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political party: Democrat | 47 | 54 | 65 |

| Political party: Republican | 68 | 59 | 67 |

| Political party: Independent | 59 | 56 | 65 |

| Political party: Apolitical | 26 | 61 | 58 |

| Political ideology: Liberal | 52 | 55 | 67 |

| Political ideology: Conservative | 62 | 62 | 64 |

| Political public: Attentive | 61 | 61 | 69 |

| Political public: Non-attentive | 53 | 53 | 62 |

| Income ($): 0-2999 | 35 | 54 | 57 |

| Income ($): 3000-4999 | 53 | 50 | 62 |

| Income ($): 5000-7499 | 54 | 55 | 61 |

| Income ($): 7500+ | 64 | 59 | 72 |

| Education: 0-7 years | 30 | 51 | 48 |

| Education: 8 years | 37 | 56 | 53 |

| Education: 9-11 years | 46 | 54 | 61 |

| Education: 12 years | 59 | 64 | 67 |

| Education: some college | 74 | 50 | 78 |

| Sex: Male | 56 | 58 | 62 |

| Sex: Female | 57 | 54 | 67 |

| Religion: Protestant | 55 | 56 | 64 |

| Religion: Catholic | 59 | 58 | 70 |

| Religion: Jew | 74 | 24 | 61 |

| Religion: Other | 53 | 55 | 67 |

| Religion: None | 60 | 55 | 63 |

| Age: Young | 57 | 48 | 72 |

| Age: Middle | 58 | 57 | 67 |

| Age: Old | 51 | 60 | 55 |

| Race: White | 59 | 59 | 64 |

| Race: Non-white | 25 | 33 | 69 |

| Social group | Elections support (%) | Congress support (%) | Federalism (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political party: Democrat | 88 | 74 | 52 |

| Political party: Republican | 89 | 78 | 81 |

| Political party: Independent | 89 | 79 | 65 |

| Political party: Apolitical | 68 | 37 | 77 |

| Political ideology: Liberal | 89 | 76 | 45 |

| Political ideology: Conservative | 90 | 78 | 80 |

| Political public: Attentive | 90 | 81 | 67 |

| Political public: Non-attentive | 86 | 72 | 60 |

| Income ($): 0-2999 | 76 | 63 | 60 |

| Income ($): 3000-4999 | 85 | 67 | 54 |

| Income ($): 5000-7499 | 89 | 76 | 66 |

| Income ($): 7500+ | 92 | 84 | 67 |

| Education: 0-7 years | 68 | 57 | 49 |

| Education: 8 years | 82 | 66 | 59 |

| Education: 9-11 years | 90 | 72 | 63 |

| Education: 12 years | 91 | 81 | 68 |

| Education: some college | 94 | 85 | 63 |

| Sex: Male | 89 | 76 | 66 |

| Sex: Female | 88 | 76 | 61 |

| Religion: Protestant | 88 | 75 | 67 |

| Religion: Catholic | 89 | 78 | 52 |

| Religion: Jew | 88 | 72 | 47 |

| Religion: Other | 87 | 76 | 66 |

| Religion: None | 92 | 76 | 55 |

| Age: Young | 88 | 81 | 61 |

| Age: Middle | 91 | 80 | 61 |

| Age: Old | 79 | 64 | 71 |

| Race: White | 88 | 76 | 69 |

| Race: Non-white | 86 | 63 | 19 |

| Social group | Achievement (%) | Bible (%) | School prayer (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political party: Democrat | 48 | 92 | 84 |

| Political party: Republican | 70 | 90 | 81 |

| Political party: Independent | 70 | 88 | 76 |

| Political party: Apolitical | 54 | 87 | 88 |

| Political ideology: Liberal | 47 | 91 | 79 |

| Political ideology: Conservative | 74 | 91 | 81 |

| Political public: Attentive | 62 | 91 | 81 |

| Political public: Non-attentive | 59 | 89 | 81 |

| Income ($): 0-2999 | 45 | 93 | 86 |

| Income ($): 3000-4999 | 54 | 90 | 86 |

| Income ($): 5000-7499 | 62 | 92 | 84 |

| Income ($): 7500+ | 67 | 89 | 76 |

| Education: 0-7 years | 36 | 90 | 89 |

| Education: 8 years | 57 | 93 | 87 |

| Education: 9-11 years | 58 | 94 | 87 |

| Education: 12 years | 66 | 92 | 86 |

| Education: some college | 66 | 84 | 67 |

| Sex: Male | 63 | 87 | 77 |

| Sex: Female | 57 | 92 | 84 |

| Religion: Protestant | 63 | 93 | 88 |

| Religion: Catholic | 56 | 91 | 83 |

| Religion: Jew | 36 | 64 | 41 |

| Religion: Other | 55 | 83 | 74 |

| Religion: None | 58 | 59 | 59 |

| Age: Young | 57 | 88 | 74 |

| Age: Middle | 60 | 91 | 82 |

| Age: Old | 62 | 90 | 85 |

| Race: White | 66 | 90 | 80 |

| Race: Non-white | 12 | 94 | 92 |

Polls During Great Depression

Another approach to ideological stability comes from polls taken during the Great Depression. Given the extent of the misery, with about one quarter of the population unemployed, why were there no mass protests? Wouldn't we expect the development of a more radical American working class? Such a movement did not occur. Why not?

Polls from the late 1930s

Polls from the late 1930s, when there was still considerable hardship, asked a sample of Americans the extent to which they believed in the free enterprise system. A clear majority of most social groups continued to support capitalism—even those who were unemployed working-class citizens. More telling, only a minority of working-class people exhibited anything like class consciousness or a sense of themselves as workers with interests in opposition to a capitalist class. So why didn't the working class become radicalized? The polls, simply, showed that they remained attached to individualistic and liberal ideals associated with the free enterprise and capitalist system. Their acceptance of dominant American values dampened the prospects of a radicalized working class movement (Verba & Schlozman, 1977).

Thus, ideological stability appears to be one factor that contributes to the stability over time of the American constitutional order.

References

Birkland, T. A. (2020). An Introduction to the Policy Process (5th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Devine, D. (1972). The political culture of the United States. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

U.S. Const. amend. XIV, §1.

Verba, S., & Schlozman, K. L. (1977). Unemployment, class consciousness, and radical politics: What didn't happen in the Thirties. Journal of Politics, 39, p. 291–323.

Wright, D. S. (1988). Understanding intergovernmental relations (3rd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.