Main Content

Lesson 2: Tailoring Evaluations, Identifying Issues, and Formulating Questions

The Importance of Making an Evaluation Plan and Tailoring an Evaluation

You probably gathered the impression from the discussions in Lesson 1 that program evaluation is a complex process with multiple aspects and multiple actors involved. That indeed is the case. To navigate through the complexity of the evaluation process, you will need to develop a road map, an evaluation plan. This plan may not work as you initially intended, and you may have to make some revisions along the way, but it is still better to start with a plan and revise it than to begin with no plan in place. It is like launching an expedition to an uncharted territory. It is better to begin with a sketchy road map than to have no maps at all.

It may be useful to remind you here that an evaluation plan is not the same as the implementation plan of a program. They are very different. For example, the implementation plan of a program should include elements such as who is doing what kind of tasks to deliver the services required by the program objectives, what organization should provide the resources (money, facilities, expertise, etc.), and the service delivery time frame. An evaluation plan, on the other hand, is about the evaluation study, not the implementation of the program. An evaluation plan should include elements such as who are the members of the evaluation team, how much money does the team have to conduct the evaluation, and the time frame for completion of the study.

The authors of our textbook use the term “tailoring evaluations” in Chapter 2. This is a good metaphor because when you conduct an evaluation study, you will have to tailor the principles and methods you have learned in this course to fit them to the real-life situation you will face. It is not the other way around: You cannot modify the real-life situations to make them fit your strict evaluation methods and designs. So, designing an evaluation is an art as well as science. (Remember the Cronbach versus Campbell debate in Lesson 1.) How you tailor your evaluation design to a particular situation is a delicate issue. Should you abandon all the scientific principles (e.g., requirements for statistical analyses) when you tailor your evaluation design? No, not really! However, you may have to make some compromises. You will see some examples in this lesson and the following lessons. Try to keep them to a minimum. Also you should recognize the compromises you made during your study openly and clearly in your evaluation report and other communications to the public at the end.

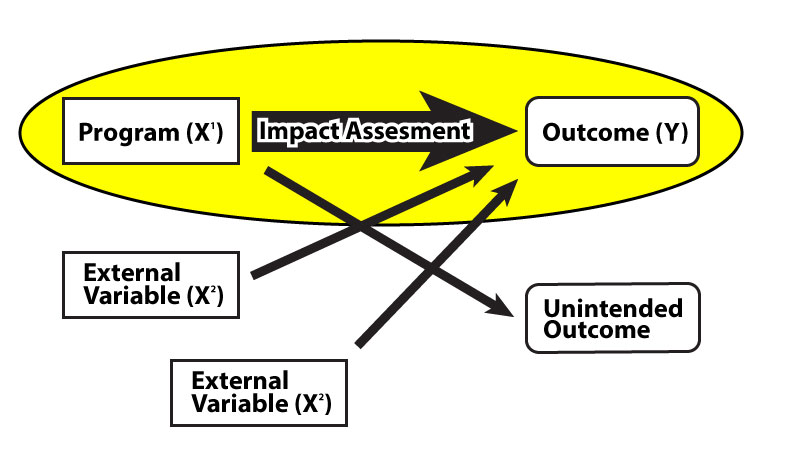

The following illustration may be useful in clarifying these points about evaluation plans and tailoring evaluations. This is what I call the “ideal model” of impact assessment (impact evaluation). (Please bear with me for this artistically challenged image! I will use it again when I discuss impact assessments later in Lessons 7 and 8 in this course.)

This illustration describes the relationship between the program and its outcome(s). A program should have a goal (or multiple goals, but I will use the singular term to simplify the discussion here). The goal would be something like reducing crime in the neighborhood, reducing teenage pregnancy rate in the state, or increasing the housing values in the city. The big question in an impact assessment is: Did our program “work” in a way that it caused the reduction in poverty/the pregnancy rate/the increase in housing values? This is a straightforward question, but it is not easy to answer, as you will see with examples in the coming weeks. How do we know, for example, that it was not our program, but other factors like the macroeconomic trends (unemployment rates, economic growth) or cultural changes in the communities under study that caused the reductions or the increases? These other factors are “external variables” in the above illustration. The big problem in impact assessment is to design a study that would measure and isolate the effects of the program from the other effects (those of external variables). You will see that there are many methods devised by statisticians that can help us to do this.

The ideal impact assessment model illustrated above reflects some of the assumptions statisticians make in devising methods like experiments. For example, the program is a box that is connected to outcomes with causal arrows. Models like this are useful: They can help us picture realities we are dealing with. The problem is that there is always a gap between the picture and the reality. The reality of program evaluation rarely matches this ideal model. Programs are not boxes that isolate what is inside from what is outside. Even if they are boxes, they usually have multiple holes and cracks on them and they “leak.” It is very difficult to isolate a program from what else is going on in real life. The connection between the program and outcomes is not linear either. Such connections may be much more complex than what a straight line represents. Also, programs may have unintended consequences, as the ideal model above recognizes; these consequences may come back and affect the implementation of the program. For example, if the implementation of a five-year crime reduction program in a community costs too much due to unanticipated circumstances, this may create a backlash in the community and the funding for the program may be cut after the first year.

So the reality is that program evaluation rarely matches the ideal model because of the complexity of real-life processes. Remember that the evaluation process is a social-political process and a scientific process. All these complexities create conflict between the requirements of scientific systematic inquiry and the need to be pragmatic in evaluation studies. This is why evaluation designs (evaluation plans) should be tailored to fit actual situations.