PADM550:

Lesson 2: Tailoring Evaluations, Identifying Issues, and Formulating Questions

Lesson 2 Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to

- understand why it is important to make an evaluation plan;

- gain a basic understanding of the five stages of program evaluation;

- discern the basic issues in defining evaluation questions in all five stages; and

- understand the difficulties in dealing with program sponsors, managers, and stakeholders in defining evaluation questions.

Lesson 2 Road Map

To Read

It is very important that you read all the required readings as listed in the course schedule for this week. The information in this lesson is not meant to replicate the contents in these readings. In this lesson references will be made occasionally to the contents of the required readings. You may want to read them before or after reading this lesson. Everyone has a different learning style and some may benefit reading them before reading this lesson, others after.

To Do

- Review the key concepts from our textbook and make sure that you are familiar with them and comfortable using them throughout the course and in your professional career.

- Answer the questions in the "Self Study" at the end of this lesson. You can discuss these questions with your classmates via the Lesson 2 Discussion Forum. I will not grade these discussions. However, it may be helpful to begin thinking about these questions now because they may help prepare you for the tests in the coming weeks.

The Importance of Making an Evaluation Plan and Tailoring an Evaluation

You probably gathered the impression from the discussions in Lesson 1 that program evaluation is a complex process with multiple aspects and multiple actors involved. That indeed is the case. To navigate through the complexity of the evaluation process, you will need to develop a road map, an evaluation plan. This plan may not work as you initially intended, and you may have to make some revisions along the way, but it is still better to start with a plan and revise it than to begin with no plan in place. It is like launching an expedition to an uncharted territory. It is better to begin with a sketchy road map than to have no maps at all.

It may be useful to remind you here that an evaluation plan is not the same as the implementation plan of a program. They are very different. For example, the implementation plan of a program should include elements such as who is doing what kind of tasks to deliver the services required by the program objectives, what organization should provide the resources (money, facilities, expertise, etc.), and the service delivery time frame. An evaluation plan, on the other hand, is about the evaluation study, not the implementation of the program. An evaluation plan should include elements such as who are the members of the evaluation team, how much money does the team have to conduct the evaluation, and the time frame for completion of the study.

The authors of our textbook use the term “tailoring evaluations” in Chapter 2. This is a good metaphor because when you conduct an evaluation study, you will have to tailor the principles and methods you have learned in this course to fit them to the real-life situation you will face. It is not the other way around: You cannot modify the real-life situations to make them fit your strict evaluation methods and designs. So, designing an evaluation is an art as well as science. (Remember the Cronbach versus Campbell debate in Lesson 1.) How you tailor your evaluation design to a particular situation is a delicate issue. Should you abandon all the scientific principles (e.g., requirements for statistical analyses) when you tailor your evaluation design? No, not really! However, you may have to make some compromises. You will see some examples in this lesson and the following lessons. Try to keep them to a minimum. Also you should recognize the compromises you made during your study openly and clearly in your evaluation report and other communications to the public at the end.

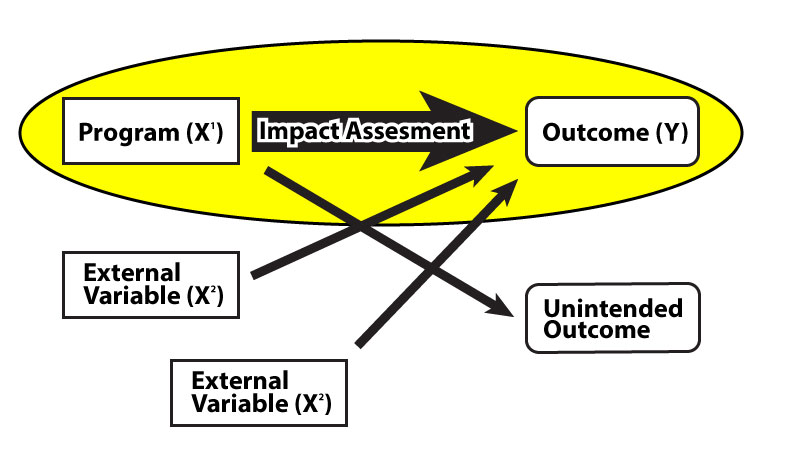

The following illustration may be useful in clarifying these points about evaluation plans and tailoring evaluations. This is what I call the “ideal model” of impact assessment (impact evaluation). (Please bear with me for this artistically challenged image! I will use it again when I discuss impact assessments later in Lessons 7 and 8 in this course.)

This illustration describes the relationship between the program and its outcome(s). A program should have a goal (or multiple goals, but I will use the singular term to simplify the discussion here). The goal would be something like reducing crime in the neighborhood, reducing teenage pregnancy rate in the state, or increasing the housing values in the city. The big question in an impact assessment is: Did our program “work” in a way that it caused the reduction in poverty/the pregnancy rate/the increase in housing values? This is a straightforward question, but it is not easy to answer, as you will see with examples in the coming weeks. How do we know, for example, that it was not our program, but other factors like the macroeconomic trends (unemployment rates, economic growth) or cultural changes in the communities under study that caused the reductions or the increases? These other factors are “external variables” in the above illustration. The big problem in impact assessment is to design a study that would measure and isolate the effects of the program from the other effects (those of external variables). You will see that there are many methods devised by statisticians that can help us to do this.

The ideal impact assessment model illustrated above reflects some of the assumptions statisticians make in devising methods like experiments. For example, the program is a box that is connected to outcomes with causal arrows. Models like this are useful: They can help us picture realities we are dealing with. The problem is that there is always a gap between the picture and the reality. The reality of program evaluation rarely matches this ideal model. Programs are not boxes that isolate what is inside from what is outside. Even if they are boxes, they usually have multiple holes and cracks on them and they “leak.” It is very difficult to isolate a program from what else is going on in real life. The connection between the program and outcomes is not linear either. Such connections may be much more complex than what a straight line represents. Also, programs may have unintended consequences, as the ideal model above recognizes; these consequences may come back and affect the implementation of the program. For example, if the implementation of a five-year crime reduction program in a community costs too much due to unanticipated circumstances, this may create a backlash in the community and the funding for the program may be cut after the first year.

So the reality is that program evaluation rarely matches the ideal model because of the complexity of real-life processes. Remember that the evaluation process is a social-political process and a scientific process. All these complexities create conflict between the requirements of scientific systematic inquiry and the need to be pragmatic in evaluation studies. This is why evaluation designs (evaluation plans) should be tailored to fit actual situations.

The Evaluation Plan

In our textbook, there is an elaborate discussion on what features of an evaluation situation should be taken into account when making an evaluation plan. I am not going to replicate that discussion here. I will simply highlight some of the important points in that discussion.

There are three important areas an evaluation plan should address:

- What are the purposes of the evaluation?

- What are the program structure and circumstances? (Click here to view)

- What are the resources available to conduct the evaluation? (Click here to view)

Purpose of an Evaluation

The purpose of an evaluation is different from the purpose (goal) of the program it will evaluate. The goal of a program may be to reduce crime in the neighborhood, reduce teenage pregnancy rate in the state, or increase the housing values in the city. A program with one of these goals may be evaluated for different purposes. In general evaluations may be conducted for one of the following three purposes:

- Program improvement (formative evaluation)

- Accountability (summative evaluation)

- Knowledge generation (academic research)

- Hidden agendas (deception, delaying an action, etc.)

There are very good discussions on each in our textbook. I want to emphasize briefly that our main foci in this course are the first and second purposes, particularly the second one. You will learn how to conduct summative evaluations with the purpose of writing up reports for your sponsors about the successes and failures of their programs. Please note that in many real-life cases, summative and formative evaluations are mixed up. The results of a summative evaluation study may be used to make improvements in programs. Particularly, the results of a process evaluation study (discussed shortly) can be used formatively to improve the implementation of a program.

Evaluation studies can also be used for knowledge generation (third purpose above). However, remember the discussion on applied research versus basic research in Lesson 1. Program evaluation is mainly considered a form of applied research, because its purposes are not knowledge generation, but to solve particular problems. However, as program evaluation developed as a discipline, its borders with basic research disciplines (sociology, psychology, economics, etc.) became blurred. This blurring is evidenced in the fact that program evaluation specialists began publishing their findings in academic journals. They also created their own discipline-specific academic journals. As you will see later in this course, we will use some articles from one of these journals: Evaluation Review.

Using evaluation study results for hidden agendas, of course, is not ethical or legitimate. The authors of our textbook mention it because it happens unfortunately. Be aware of it!

Program Structure and Circumstances

An evaluation plan should include information about the structure and circumstances of a program. The authors of our textbook specifically stress the following three structural or circumstantial elements of a plan:

- Stages in program development

- Administrative and political context of a program

- Conceptual and organizational structure of the program (program theory)

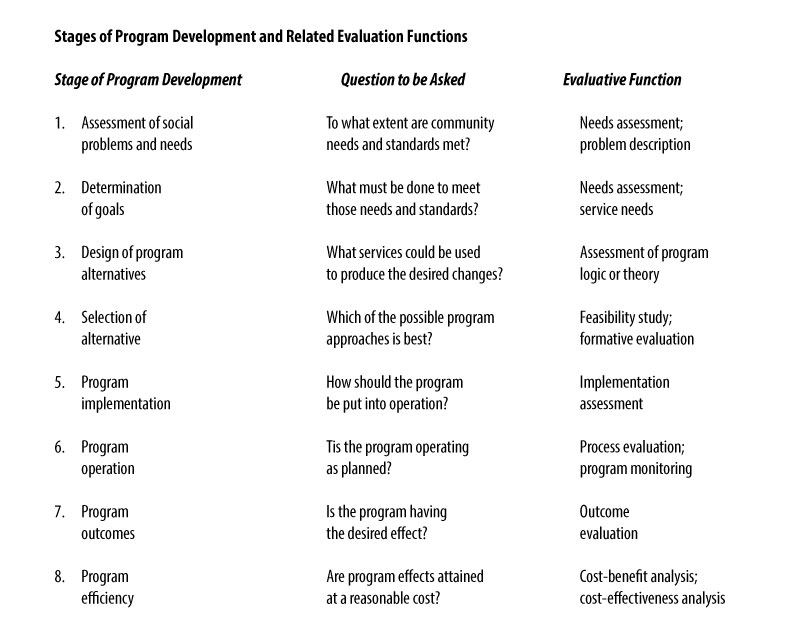

The stages in program development and the corresponding program evaluation functions are summarized in Exhibit 2-e in your textbook, which I copied here. This is an instructive exhibit because it provides an overview of what we will spend most of time for during this course. So I recommend that you study the exhibit and related discussion in the book carefully.

Stages of Program Development Exhibit 2-e

Figure 2.2. Image created base on Exhibit 2-E. Evaluation: a systematic approach by Rossi, P. H., Lipsey, M. W., Freeman, H. E. Reproduced with permission of Sage Publications Inc. Books in the format Post in a course management system via Copyright Clearance Center.

You will remember from Lesson 1 that typically there are multiple stakeholders in program evaluation studies. They are sources of information for your study and they will try to influence your study legitimately or not so legitimately. Rossi and his colleagues call these attempts at influencing circumstantial issues in program evaluation the “administrative and political contexts of the program.” These contexts should be factored into evaluation plans carefully. With a good plan, the evaluator can take advantage of the good information and support some of the stakeholders can provide and prevent unduly influences.

The conceptual and organizational structure of the program, otherwise known as the program theory, is a crucial element of an evaluation plan. As you will see shortly in this lesson and in more detail in Chapter 5 of our textbook, a program theory is the image of how a program is supposed to work. This image is important to discern because only if you have an accurate and clear image, you can determine whether the program worked or not.

Availability of Resources for Evaluation

Obviously no evaluation plan is complete without an estimate of the resources available to the evaluator. The availability or lack of these resources may make or break the evaluation study. It is not necessary to repeat the discussion on this issue in our textbook here. Briefly, an evaluation plan should include

- personnel;

- materials;

- equipment;

- facilities;

- specialized expertise;

- support from program management;

- access to records; and

- time.

Stages of Program Evaluation

We already touched on the stages of program development (Table 2.2). Now we can be more specific. There are different forms, or stages, of program evaluation. In Rossi and his colleagues’ classic formulation, five forms, or stages, of program evaluation are identified:

- Needs assessment (determining the need for a program) (Chapter 4)

- Program theory (figuring out the design of a program) (Chapter 5)

- Process evaluation, monitoring (studying if the program was implemented properly, as designed) (Chapter 6)

- Outcome and impact assessments (determining whether the desired outcomes have been reached and whether they have been reached because of the implementation of the program) (Chapters 7–10)

- Efficiency assessment (cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses to determine whether reaching the desired outcome was worth the price paid) (Chapter 11)

If you want to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of a program, you will complete all of these stages in a more-or-less sequential order. That is why they may be called “stages.” However, as Rossi and his colleagues recognize, evaluations usually are not done in a sequence. In many cases, the evaluator may be able to conduct a study in only one of the five stages. You will see in the coming weeks that conducting an evaluation study is not an easy task and it will take large amounts of resources and serious commitments by many parties (e.g., program administrators, policy makers, evaluators, and many other stakeholders) for long periods of time to conduct a comprehensive evaluation. That is why, realistically, as an evaluator you can only do one of the five at a time.

Our discussions of these five stages will take most of our time during this semester. We will spend one week on each stage, but our discussions of Stage #4 (outcome and impact assessments) will extend to multiple weeks. You have probably noticed that in our textbook, four chapters are allocated to the discussion on outcome and impact assessments and for good reason. In it a very important question is asked: Did the program reach its goal(s) because of our program? As you will see in the coming weeks, this is not an easy question answer. Sophisticated methods must be applied to answer it.

Consider this example: The goal of a volunteer patrol program in a neighborhood is to reduce crime. How would you know if the program worked? To answer the question, you would have to decide on what you mean by crime (what kinds of crime: thefts, assaults, murders), a time frame, and how much reduction in crime is acceptable. You may observe that the car thefts in the neighborhood are down during the program’s period of the implementation, but sexual assaults are up in the same period. Did the program work? If the program takes one year to yield successful results, and you take measurements at the end of the sixth month and find that it has not reduced the crime rate, you may be wrong because you have not given the program enough time to generate results. Also, you should decide how much reduction in crime would be counted as a success. If it drops 10% in one year, is that enough? Or, should it be 40%? To complicate the matters even more, even if you observe that the crime rate (let’s say the rate of thefts) has declined in the time-frame you decided and at the amount you specified, what if that was because of the general economic conditions, not because of the program? Perhaps, as the economy got better, people found jobs to sustain themselves and their families better and stopped stealing. How would you sort out the specific impact of the program while economic and social conditions are obviously were also affecting what happened in your neighborhood?

There are methods of disentangling the effects (impacts) of a program from other factors like economic and social conditions. You will learn some of the basic methods in this course. It will take more than a week to clarify what these methods are and how they work. This is why we will spend more time on outcome and impact assessments.

I recommend that you keep the points I made in this section in mind when you read the chapters in the coming weeks. I also would like you to keep this in mind: How Rossi and his colleagues describe program evaluation in their book is not the only way to practice or theorize program evaluation. There are different schools of thought (or “models”) in program evaluation. In this course, we will follow Rossi and his colleagues’ school of thought because it is the most well-established model. I will call it the “Rossi model” or the “orthodox model.”

To understand why it may be called the orthodox model, I recommend, you read about the history of program evaluation (for example, Alkin’s book, Evaluation Roots [Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004]). In brief, Rossi was one of the founders of the discipline called program evaluation. The book we are using in this course is one of the oldest ones in this field. The current edition of the book is the product of many decades of evolution and refinement. It is considered a classic. (Unfortunately, Rossi passed away in 2006, and the future of this book is uncertain.)

The Rossi model is not the only one, but it is the most mainstream model. I will not discuss all the other models in this course. However, I do not want to bias you against them. The reason I prefer using the Rossi model is because it represents the mainstream, and his book is probably one of the most comprehensive ones available. After learning this model, even if you do not like it and want to learn about the others, this course will provide you with the basic understanding of the orthodox (mainstream) model. If you wish to criticize this orthodoxy, you will know what you are criticizing.

Evaluation Questions and Methods

As we learned in Lesson 1, program evaluation is a kind of applied research. Therefore, many of the principles of conducting research that you learned in basic research methods courses (e.g., PADM 503 in our program) should be applied in it. One of the big issues in any kind of research is how to ask your research questions. In the case of program evaluation, they are evaluation questions. I would like to stress a few important points here based on the information in our text.

What makes a good evaluation question? To ensure that your evaluation questions are reasonable and appropriate, ask sponsors and stakeholders for their views and inputs. Remember, however, our discussions on the influences and involvement of stakeholders in evaluation research: their inputs may be very useful (because they know the situation and problems better than an outside evaluator), but they may also want to influence the research process and its findings to support their positions and promote their influences.

In addition to asking sponsors and stakeholders, the evaluator has to use his or her own expertise, experience, and judgment in determining what a good evaluation question is. One key component to evaluation questions is to determine if evaluation questions are answerable. They are answerable if

- they are stated clearly and specifically (no vague words/concepts are used);

- relevant criteria can be applied in collecting evidence to answer them (you should remember this concept as the operational definition from your basic research methods course, such as P ADM 503); and

- expertise and information sources are available to answer the questions.

As the authors of our textbook discuss in detail, different evaluation questions should be asked at the different stages of program evaluation: needs assessment, assessment of program theory, assessment of program process, outcome and impact assessment, and efficiency assessment. The following is not a substitute for their excellent discussions and examples, but just a brief summary of a few important points.

Needs Assessment Questions

The overall question in needs assessment is this: Is there a need for a program? To answer this question, an evaluator first answers the following more specific questions:

- What is the population of individuals, groups (e.g., households, neighborhoods, organizations), or units of objects (e.g., houses, factories) that the evaluator has been asked to study? For example, how many individuals have been infected with the HIV virus? Or, how many houses need repair?

- What are the specific needs and what should be addressed? What do these poor children need, for example: food, education? How much service should be delivered to whom in a future program? How many additional teachers would be needed for how long, for example?

- How can the specific needs be measured? This may sound like an easy question to answer, but it may actually be very difficult, time consuming, and even contentious. As an example, consider this: How should we determine how many poor children are in the community we want to study?

Easy, right? You can simply apply the “poverty line” statistic that is regularly calculated by the U.S. Census Bureau. (For more information, see the Census Bureau website, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty.) Those children whose families are under the line are poor and those above it are not. This is a common method used in many poverty studies. However, it is not free of problems. Does the U.S. Census Bureau’s statistic truly measure poverty? It is based on a series of assumptions that are not necessarily agreed upon by everyone. Just keep this problem in mind for now; I will come back to it with an example in the next lesson.

Program Theory Questions

As I mentioned earlier in this lesson, a program theory is the conceptual and organizational structure of a program; an image of how a program is supposed to work. This image should be depicted and then scrutinized to make sure that it can truly guide the research process in the following stages of program evaluation. In two weeks, we will discuss the details of these issues. The following is a preview.

The overall question in assessing a program theory is this: Can this program be evaluated? More specifically, first, what is the accurate image of the program as it was/is conceived by the program sponsors and administrators? In other words, how is the program supposed to work? This may sound easy, but in real-life evaluations it takes quite a while and the cooperation of sponsors and possibly other stakeholders to figure it out. An image of the program should be developed, including

- program goals;

- target population; and

- the organization that will implement the program.

The second more specific question in assessing a program’s theory is this: Is this program evaluable? Once you pictured the goals, population, and the organization that will implement the program, you should determine whether this information is sufficient to evaluate the program. If you are asking “Why should it not be sufficient?” please be patient with me until we discuss the details of the issues in program theory.

Process Evaluation Questions

In a process evaluation study, the overall question is this: Has the program been implemented how it is supposed to be implemented, as it was depicted in the program theory? Why is this an important question?

First, it is an accountability issue. If the program administrators and staff take the money allocated for program implementation and did not do what they were supposed to do, they should be held legally and ethically responsible for their actions. It is important to find out what exactly they did with the money and resources they used.

Second, process evaluation is an important stage before an impact assessment, which is the probably the most important stage in program evaluation. The problem is this: If the program was not implemented properly, then it is not meaningful to conduct an impact assessment. In an impact assessment study you will try to answer the question: Did the program reach its goals? You cannot answer that question without first making sure that the program was implemented as intended in the first place.

Process evaluation is analogous to assessing the skills of a marksman (how close the shots were to the bull’s-eye, for example). If the gun the shooter used was not calibrated properly (not adjusted for precise aiming), then it does not make sense to ask if the marksman was successful in hitting the target. He or she had a faulty gun.

The following questions are typically asked in process evaluation:

- Was there enough money for implementation?

- Were there enough personnel and expertise to implement the program?

- Were the program facilities adequate?

- Was the organization that was in charge of the implementation working properly?

Outcome and Impact Evaluation Questions

Outcome(s) and impact assessments are the most important stages in program evaluation. (They may be considered two separate stages or two sub-stages in one stage.) At this stage, we want to find out if the program worked. Did it “work” in the sense that the goals set by the program sponsors in the beginning were reached? Or, to what extent have the goals been reached?

There is a difference between outcome(s) evaluation (assessment) and impact evaluation (assessment). Outcome evaluation is easier and comes first.

The overall question for an outcome evaluation is: Did we reach our goal? For example, has the percentage of children without health insurance in the community been reduced by 10% in the last five years, as was intended in the beginning of the program?

Impact evaluation is more difficult and can be conducted either after an outcome evaluation is completed, or in conjunction with it. The overall question for impact evaluation is: Did we reach our goal because of our program? For example, did the percentage of children without health insurance in the community drop by 10% in the last five years because of our program? Or were there some other factors that did it, or contributed to the change along with our program? Then what percentage of the drop was caused by our program?

The phrase “because of our program” is the key to understand the nature of impact evaluation. The term suggests that we are looking for a causal relationship between our program and the measured outcomes. You may remember from your introductory research methods course that establishing causality between variables is a major challenge in the social sciences. There are methods you can use (we will discuss them in a few weeks), but you still may not be 100% confident that you have found a causal relationship. We will discuss the delicate issues in establishing causality later in this course.

Efficiency Assessment Questions

If you can reasonably demonstrate that the program you have studied caused the outcomes (i.e., the program reached its goals), then the next, and final, stage of program evaluation is to assess the efficiency of the program. The overall question at this stage is this: Was the cost of the program worth reaching its goal(s)? Of course, it is ultimately the judgment of the sponsors, policy makers, or grant givers that will determine whether the success of the program was worth its cost. There are methods of making the cost calculations, mainly cost-benefit analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. We will discuss these concepts toward the end of the course (in Lesson 11).

Obtaining Input in Determining Evaluation Questions

In our textbook, there is generic advice you can use in formulating the evaluation questions in all five stages. Here are some highlights from the book:

- Ask program sponsors first what would be appropriate and relevant questions to ask.

-

Also ask stakeholders about appropriate and revelant questions. The sponsors of a program are usually obvious and well-known, but it may take some effort to identify the stakeholders. The authors of our book recommend identifying who the stakeholders are by using

- the snowball sampling approach;

- telephone and personal interviews; and

- focus groups.

The authors also provide a generic list of possible stakeholders. I recommend that you consult this list in your future studies. In addition to the policy makers and obvious program sponsors, the authors list the following:

- Target participants of a program (wait until next week for a discussion of “targets”)

- Program managers

- Program staff

- Program competitors (Yes, there may be other programs competing against the one you are evaluating. Obtaining the sponsors, managers, and/or staff of them may give you a better perspective in designing your evaluation questions.)

- Contextual stakeholders (This includes organizations, groups, or individuals who are in the area the program is implemented and who may be affected by its implementation, although this may or may not be the goal of the program sponsors or policymakers.)

- Evaluation and research community (Remember that evaluation researchers are typically academics and they review and evaluate others’ studies for accuracy, integrity, and appropriateness. You can seek their advice or look into previous similar studies for guidance in designing your questions.)

It is important to identify the stakeholders and ask for their input, but remember the downside of doing this as well. They may try to influence your study in order to promote their own interests. Also remember that multiple stakeholders will probably give multiple and possibly conflicting forms of advice as to which questions are relevant and appropriate. Also, it is highly likely that stakeholders may have not have been involved in any program evaluation studies before and therefore may not know how to formulate questions.

Another possibility is that even sponsors or stakeholders may not know much about their own programs, or they may have a vague understanding of the programs! Are you surprised? Don’t be. Many programs start within political processes (fighting, debating, interpreting differently what the goals are, etc.) and even policy makers, sponsors, or program managers may not have a clear understanding of their goals and how programs are supposed to work. In the end, it is the evaluator’s responsibility to use his or her expertise and experience in guiding stakeholders to formulate evaluation questions. Our discussions on program theory in a couple of weeks will give you a better sense of what this means.

The authors of our textbook recommend that evaluators discuss the following with stakeholders to guide their formulation of evaluation questions:

-

Why is the evaluation needed?

- What are the program goals and objectives (not the goals of the program evaluation)? (See the guidelines for specifying objectives in the book.)

- What are the most important questions for the evaluation to answer?

Lesson Summary

We discussed why it is important to make an evaluation plan and how an evaluation plan is different from the plan of implementation for a program. When making your evaluation plans, you will have to use the methodological principles you will learn in this course, but you will have to "tailor" them to the specific conditions of the program you are going to evaluate.

An evaluation plan should include information about the purposes of the evaluation, the program structure and circumstances, and the resources available to conduct the evaluation. We discussed the issues in each of these areas.

In this lesson you have been introduced to the concept of stages of evaluation. We discussed the five stages briefly: needs assessment, assessing program theory, process evaluation, outcome and impact assessments, and efficiency assessment. We will spend most of time in this course discussing the details of the issues and methods used at these stages.

In this lesson, we summarized the kinds of evaluation questions that can be asked in each stage of program evaluation and then the generic advice given in our textbook on how to gather information for and how to formulate these evaluation questions.

Self-Study

Read the following case description and apply what you have learned in this lesson to it. There are some specific questions after the case description. You can discuss these questions with your classmates via ANGEL in the Lesson 2 Discussion Forum. I will not grade these discussions. However, it may be helpful to begin thinking about these questions now, because they may help you prepare for the tests in the coming weeks.

The staff of the Women’s Resource Center in Smallville has become increasingly concerned about the high levels of unemployment and underemployment and the low earnings of female heads of households in their town. The members of the staff learned that these women were unable to make rent payments, pay utility bills, or provide necessary clothing for their children. They also learned that the existing public programs were ineffective in solving the problems of these women. The staff members have decided to explore the specific needs of the female heads of households and devise new programs if necessary. They have contacted you, an expert in program evaluation, to help them conduct a preliminary study. You agreed.

(Adapted from Freeman, Rossi, & Sandefur. (1993). Workbook for evaluation (5th ed., p. 29). Sage.)

- How would you determine the appropriate evaluation questions in this study?

- Who would you interview for this purpose?

- Who would be the program sponsors?

- Who would be the stakeholders? How would you identify them?

- How would you deal with the problems that may arise as results of the sponsors and stakeholders trying to influence the evaluation process?

If you have extra time read Chapters 4 and 5 in Chen’s book Practical Program Evaluation. Then rethink the questions above. Did the information in Chen’s book help you answer them better? How?