PSYCH270:

Lesson 1: Abnormal Behavior

Introduction

Welcome to Psych 270, Introduction to Abnormal Psychology. We will be exploring the world of abnormal psychology over the next several months and along the way will encounter a large amount of content starting with baseline information in the first three lessons and eventually touching upon various families of mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. We will also learn about mental health-related topics such as suicide and a few more obscure yet very interesting topics such as dissociative disorders.

One advantage that we have on our journey is that the subject matter is inherently interesting to most people. Mental illness is a fascinating and engaging topic that can promote a great deal of thought and discussion.

This course was created by Dr. David J. Wimer during the summer of 2016, but an on-line course such as this one is like a relay race with many scholars cultivating it over time. Your instructor may not be the original creator of the course and if not then he or she will provide their own unique perspective by putting their own spin on the subject matter.

I am choosing to write in first person because the narrative will be less clunky and more engaging that way; also, I am a published science fiction author and parts of my novels and many of my short stories are in first person so it is a format that I'm comfortable with. Thus, when I say "I", I am referring to Dr. David J. Wimer.

Our exposure to the subject matter in this course will be a combination of the textbook, media such as the Depression: Out of the Shadows documentary, and the online commentary. In the online commentary I see my role as that of a "tour guide" in that I will add context above and beyond the textbook while also pointing out important subject matter that may receive more emphasis on exams.

So what is "abnormal"? As we will learn in this first lesson, "abnormal" is a highly subjective term and there are many factors that need to be considered when determining abnormality.

Why do people behave in abnormal ways? For example, why would a celebrity like Ariana Grande do something like lick a donut and put it back on the shelf?

Deciphering the cause (or "etiology") of abnormal behavior is an important aspect of abnormal psychology.

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson you should be able to:

- Define key terms and concepts.

- Understand the concept of abnormality.

- Differentiate among the various standards and criteria for determining abnormality.

- Understand the basics of psychotherapy.

- Think critically about the current and future trends in abnormal psychology.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

Abnormal Psychology Terms

Let’s start with the definition of this course.

Let’s break down this definition. Who determines what is or is not abnormal? There is some degree of subjectivity to this. There are certain entities with the power to determine standards of abnormality, such as the American Psychiatric Association or the World Health Organization. A major part of this chapter is learning some of the criteria for judging abnormality, but for now let’s go over a few more important terms.

Etiology = The possible causes of a mental disorder. The etiology of a disorder is usually a combination of nature (i.e. biological or genetic) and nurture (i.e. learned or environmental) factors.

Psychodiagnosis = An attempt to describe, assess, and systematically draw inferences about an individual’s psychological disorder. We will learn about diagnosis in more detail in Lesson 3.

Psychotherapy = A program of systematic intervention designed to improve a person’s affective (emotional), behavioral, or cognitive state.

We will examine psychotherapy in more depth on the subsequent pages, starting with our first “Fact or Myth” game of the semester:

Psychotherapy

Fact or Myth?

Psychotherapy is more effective than medication for most mental disorders.

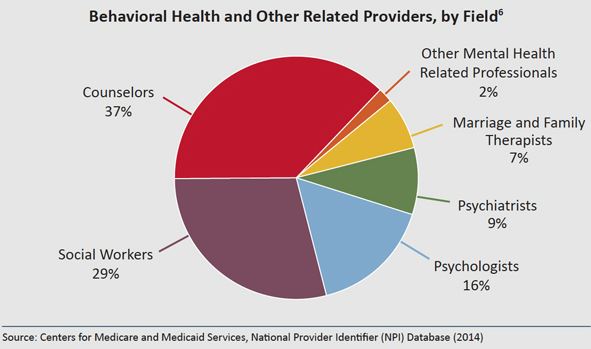

The mental health world is very diverse and convoluted and can thus be a little confusing, and there are over 400 different kinds of psychotherapy (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). Psychotherapy is performed by many different people with various educational and training backgrounds. The pie chart in figure 1.1 is from a study conducted in May of 2014, and as you can see Ph.D.-level psychologists only make up about 16% of all mental health professionals. Master’s-level clinical social workers and mental health counselors make up a large majority of those who conduct psychotherapy and other forms of mental health treatment (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2014).

Explanations and treatments of abnormal behavior vary based on the mental health professional’s philosophical and theoretical lens, and those 400+ types of therapy become less confusing and less intimidating when you realize that most of them can be boiled down to the four main theories of psychotherapy: Psychodynamic, Behavioral, Cognitive, and Humanistic. Each of these four main theories enacts change through a different route or focus:

Psychodynamic

A key for psychodynamic therapy is “consciousness raising”, or raising awareness of one’s maladaptive patterns that may stem from problematic childhood experiences. For example, let’s say that a man was overprotected by his mother as a child so now he is very clingy and dependent in romantic relationships; a psychodynamic therapist would help the client to develop insight by becoming more aware of this relationship pattern and would then use that insight to improve his relationships.

Behavioral

The major key for behaviorists is, not surprisingly, to simply change a client’s behavior in a concrete way. For example, if a client is addicted to pornography then a behaviorist would focus on reducing the number of times per week that the client watches pornography.

Cognitive

Cognitive therapists tend to focus on the “inner dialogue” that we all have within our minds, and they typically try to change irrational or negative/self-defeating thoughts. For example, let’s say that a client with depression keeps having thoughts like “I’m a failure” or “I’m worthless”; a cognitive therapist would scientifically examine those thoughts with the client to point out how they’re not necessarily true while also coming up with more positive thoughts such as “I have value”.

Humanistic

Humanistic therapists use empathy, support, and a nonjudgmental stance toward clients to validate them and make them feel safe to be themselves. They also use techniques such as reflection of feeling to help a client engage in emotions that they need to get in touch with. For example, imagine that a psychotherapy client had a loved one die a few years ago but never really dealt with the emotions surrounding the loss; a humanistic therapist would have the client experience those emotions and would then validate them to ultimately help the client come to terms with the loss.

Many psychotherapists nowadays are eclectic, meaning that they utilize multiple theories instead of just one. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is obviously a combination of the two, which brings us to our next Fact or Myth.

Brainstorm Ideas

Think about these questions as you generate thoughts and ideas in preparation for the Lesson 1 Discussion Forum questions found at the end of the lesson.

- What are some possible reasons why therapy is more effective than medication in most instances?

- What are some reasons why many people think or hold onto the belief that medication is more effictive?

- What are some explanations as to why medication by itself has a high relapse rate?

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Fact or Myth?

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy is the most effecitve form of psychotherapy.

Imagine a little league referee who has a child on one of the teams so they call more penalties on the opposing team (possibly without even being aware of it) – that’s another example of an allegiance effect.

Thus, the belief that CBT is the most effective form of psychotherapy is a myth. All four theories of psychotherapy mentioned above have a great deal of empirical support (Lambert, 2004; Wampold, 1997). What matters is how well and how appropriately you utilize a theory, rather than which theory you use – which leads to our next topic…

Common Factors Model

The Common Factors Model (Frank & Frank, 1991) conveys that any psychotherapy theory can work as long as the therapy incorporates some universal, effective factors. Imagine a stew that will taste good as long as it includes four key ingredients. The four common factors are as follows:

Therapeutic Relationship

The therapeutic relationship is considered by many psychotherapy researchers to be the most important determinant of positive change (Lambert, 2004), and it is the most important of the four common factors. A strong therapeutic relationship is a foundation of trust that allows psychotherapy to be more fruitful (regardless of theory). For example, clients are less resistant or defensive and interventions work better when a strong therapeutic relationship is in place. Doing certain interventions or techniques without a strong therapeutic relationship in place is like taking food out of an oven before it’s cooked or walking a tightrope without a safety net.

Healing Setting

This refers to a comforting, healing place in which a client can get into the “mode” of working on oneself. It’s an atmosphere that creates a relaxed and open feeling within the client, which subsequently facilitates dialogue and disclosure. An ethical, empathetic therapist can create this by making the client feel welcome and safe. An example from my own career when there was not a good healing setting was when I was attempting to use relaxation techniques on a client with panic disorder but the clinic was under construction and workers in the next room were using loud drills and other construction tools, which exacerbated my client’s nervousness. That was definitely not a healing setting!

Accepted Rationale

This basically means a shared belief between client and therapist; both the client and therapist must be optimistic about the prognosis to a reasonable degree and must believe in the style of therapy being used and/or the content of each session. This does not mean that the client and therapist have to have the exam same worldview or life philosophy, but it does mean that they need to be “on the same page” regarding the therapy taking place. For example, if a therapist uses guided meditation for a client’s anxiety both the therapist and client must believe that the technique will be helpful.

Rituals or Procedures Requiring Active Participation

This refers to the events and/or techniques that take place in a therapy session; ideally, the client must actively participate in the techniques and activities rather than being passive or disconnected. For example, if a therapist challenges a client’s negative, irrational beliefs the client must actively work with the therapist in coming up with ways to refute those negative beliefs. The term “ritual” refers to repeated things performed in session. An example of a ritual in therapy is the “check in” and “check out” procedure during a typical group therapy session, which is when each client in the group talks about how their week was and so forth (check in) and then when everyone at the end processes how the session went (check out).

Now that we have established ways in which psychotherapy works, let’s discuss an important goal of mental health treatment: moving a client to a higher stage of change.

Stages of Change

Mental health practitioners obviously want their clients to improve, and a major goal of psychotherapy is for the client to progress to a higher stage of change in the model engendered by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983), with the ultimate goal being the client not needing treatment anymore. Clients progress and regress (as relapse is part of the process and change is rarely linear) through the following six stages:

Precontemplation

In precontemplation, the client is in denial or uninterested in changing. This stage is very common among court-mandated clients and others who do not want to be in therapy, and clients in this stage can be resistant and difficult to work with. However, there are ways to help clients progress through this stage, such as the empirically supported technique known as motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991).

This “stages of change” model can be used for many things and not just psychotherapy, so I’m going to use the example of losing weight and getting in better shape as we go through the stages. If someone is in precontemplation then they think they’re fine and they are not interested in changing.

“I’m fine – I don’t need to lose weight”

Contemplation

In this stage, the person is aware of the problem (or they move past denial to admit that they have a problem) and they have thoughts about changing. Essentially, they’re starting to think about change but they don’t have a concrete plan yet.

“Maybe I need to start exercising and losing weight”

Preparation

In the preparation stage the individual has an actual, concrete plan to change – but they haven’t implemented it yet.

“Next week I’m going to get a gym membership and I’m going to start a diet program.”

Action

This is where you want clients to be; the individual is implementing the plan(s) from the previous stage and is doing what they need to do to change.

“I’m going to the gym several times per week and I’m actively engaged in a diet program.”

Maintenance

As the name implies, this stage is about sustaining the change and progress from the action stage; essentially, the maintenance stage is about preventing relapse.

“I renewed my gym membership, I still go several times per week, and I’m sticking with my diet.”

Termination

This is when the client no longer needs treatment. In psychotherapy, termination typically involves wrapping up treatment and coming up with strategies for maintaining progress after treatment is over.

A caveat to this last stage regards drug and alcohol treatment: when it comes to addiction, nobody is ever considered to be “fully recovered”. People prefer to use the term “in recovery” because someone can be clean for 20 years but still relapse. Thus, if you’re treating someone for addiction then there is no termination stage per se and the client just stays in maintenance long term.

Self-Check

The most difficult state to transition into is...

We’ve taken a sidebar journey to peek behind the curtain and examine the inner workings of psychotherapy, but now let’s get back to the major focus of this lesson:

Brainstorm Ideas

Think about this question as you generate thoughts and ideas in preparation for the Lesson 1 Discussion Forum questions found at the end of the lesson.

- What are some potential resons why it is so hard for people to go from preparation to action?

Criteria for Determining Abnormality

According to the textbook, mental disorders involve behavior that departs from some norm and harms the affected individual or others (Sue et al., 2016). In this section we will go over what are called the “4D Criteria”, or the four major factors involved in judging psychopathology:

Distress

This involves experiencing unpleasant mental or physical health symptoms. The textbook does not mention physical symptoms but I’m adding it here because physical discomfort or distress can worsen psychological distress and vice versa; e.g., chronic pain is a huge issue in the mental health world right now.

Many of the diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5 involve distressing symptoms such as irritability or sadness.

Deviance

Abnormal behaviors differ from the typical experiences of most people, and can sometimes deviate from the shared, agreed-upon reality most of us encounter.

Hallucinations and delusions are considered psychologically deviant experiences because they are not something that one typically encounters in normal human experience. Thus, hearing the voice of Satan or believing that you are a famous Hollywood actor when you are not are considered deviant and abnormal.

Delusions = False beliefs held despite contradictory, objective evidence.

A clinical delusion is one that someone believes even when it is clearly wrong. For example, suppose that a man has a delusion of jealousy and he believes that his partner is cheating on him. He is 100% convinced that his partner is cheating on him and he even hires a private investigator to follow them. The man will still be convinced of the infidelity even if the private investigator shows him definitive proof that his partner is not cheating.

We will learn more about hallucinations and delusions (which are known as “positive symptoms”) when we discuss psychotic disorders in Lesson 12.

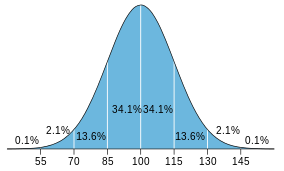

Another form of deviance is statistical deviation, or being discrepant based solely on raw numbers. Let’s consider I.Q. scores as an example of this. The average I.Q. score is 100, and a standard deviation is 15. That means that someone’s I.Q. score is statistically deviant if it is below 85 or above 115. You can probably think of some issues with using statistical deviation as a criterion for abnormality: judging someone based solely on a number does not consider context, and it may lead to pathologizing people who are actually high functioning. Can you think of other problems with this approach? Can you think of potential benefits of statistical deviation?

Dysfunction

This domain refers to how well one can function in life. Life functioning is a very important factor that clinicians need to take into account when assessing a client. For example, I work at a college counseling center and I always ask my student-clients if their grades dropped off recently because of their symptoms – that’s one way of judging the impact that their mental health problems may be having on their life.

The DSM-IV-Text Revision (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) featured something known as the “Global Assessment of Functioning” or GAF scale. A client’s GAF score was determined by his or her level of distress or symptomology (which is obviously related to the Distress domain from earlier) combined with his or her level of life functioning, which is this Dysfunction domain.

There are various areas of life functioning that one can consider: school or academic functioning, occupational functioning, social relationships, and day to day tasks such as grooming or driving a car are common examples.

Dangerousness

This domain is fairly self-explanatory: can the person be considered a danger to self or others? It is rare for mentally ill individuals to commit violent crimes (Sue et al., 2016), but it’s still important for clinicians to assess for dangerousness. We will discuss this issue in more detail in Lesson 2. For now, however, just know that if someone is dangerous then they can certainly be considered abnormal.

Frequency & Burden of Mental Disorders

Epidemiological data reveals how common or rare certain health conditions are.

The following epidemiological terms are very important to know, and you will need to know them throughout the entire course:

Incidence

For example, in the United States, approximately 29,218 new cases of Hepatitis C occurred in 2013, which is approximately 1 out of every 10,918 people or .009% of the population (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, CDC, 2016).

Prevalence

For example, according to the CDC (2016), approximately 3.5 million Americans are believed to be currently infected with Hepatitis C; this is approximately 1% of the population.

Lifetime Prevalence

Hepatitis C is usually a chronic condition, so let’s switch to clinical mood disorders as an example. According to the Harvard Medical School (2007) the lifetime prevalence for a clinical mood disorder is approximately 21.4% of the American population, meaning that more than 1 out of every 5 Americans meets the criteria for a clinical mood disorder such as depression or bipolar.

A Brief History of Mental Illness

Considerations of abnormal behavior and mental illness are rooted in the system of beliefs that operate in a given society at a given time (Sue et al., 2016). Thus, we must consider historical context in our discussion of abnormality. One could easily teach an entire course on the history of mental illness (and the author of this course has), but for the sake of time we will focus on a few things: demonological explanations of mental illness in the middle ages, the rise of naturalism and moral treatment, and the mental asylum movement.

The Western World reverted to demonology as the dominant explanation for mental illness following the collapse of the Roman Empire.

In order to counteract threats to the church’s power, Pope Innocent VIII called for the identification and extermination of witches in 1486; this led to the publication of The Malleus Maleficarum (“Witch’s Hammer”) two years later. Clergy wrote this tome to suppress revolutionary individuals and groups who the church saw as a threat, including the mentally ill in many cases. The “treatment” for mental illness was usually death or torture.

Historians estimate that at least 100,000 people were executed as witches from the late 1400s through the late 1600s, and approximately 85% of them were women (Viney & King, 2003).

Johann Weyer (1515-1588) was an important figure who challenged the prevailing beliefs about witchcraft, and he argued that many individuals who were persecuted as witches were actually mentally ill. This was an early, naturalistic explanation of mental illness.

Copernicus showing that the earth revolves around the sun is an example of Naturalism. Naturalism met a great deal of resistance early on (such as Copernicus being jailed for his findings), and naturalistic explanations of mental illness met even more resistance.

Phillipe Pinel worked within the naturalistic framework and instituted the moral treatment movement around the year 1800 in France. Pinel freed the mentally ill from chains and dungeons and promoted healthy behaviors. He noted how the patients responded positively to such humane treatment, which seems obvious today but was revolutionary then. Moral therapy involved the following practices (Viney & King, 2003):

- Individualized care

- Occupational therapy

- Exercise

- Recreation

- Religious lessons

- Arts & crafts

Be sure to pay attention in the textbook to the contributions of William Tuke, Benjamin Rush, Dorothea Dix, and Clifford Beers.

Mental Asylums in America

The growth of cities in America led to the need for mental asylums, which were an example of good intentions that went bad (Benjamin & Baker, 2004). Families had difficulty caring for the mentally ill and so they transferred care of the mentally ill to public institutions.

The first American mental asylum opened in Philadelphia in the 1750s (Benjamin & Baker, 2004).

Asylums got larger and larger as demand grew and the moral therapy of Pinel eventually became too difficult to apply because of overcrowding in asylums. By the late 1800s mental asylums became like warehouses for mentally disturbed people, and in 1869 Willard State Hospital in New York was the first hospital specifically designated for chronic cases. Asylum admissions went up approximately 830% across the 19th century (Benjamin & Baker, 2004). Hospitals were eventually forced to release patients who were not cured simply due to lack of room.

The deplorable conditions in mental asylums combined with revolutionary new drug treatments led to John F. Kennedy signing the 1963 Community Mental Health Centers Act into law (Benjamin & Baker, 2004).

Once again, this was good intentions gone awry. The 1963 Community Mental Health Centers Act was ultimately a failed attempt to improve care for the mentally ill by allowing their families to take care of them while they received services at an outpatient community mental health center. The problem with this is that many of the patients were abandoned or forgotten by their families and thus had nobody to turn to, so the act ended up swelling the ranks of America’s homeless and the effects of this are seen to this very day as a large proportion of homeless individuals are mentally ill (Benjamin & Baker, 2004).

Additional Concepts

Be sure to carefully read about the following concepts in the textbook:

- Biological viewpoint

- Psychological viewpoint

- Cathartic method

- Intrapsychic

- Multicultural psychology

- Positive psychology

Present and Future Trends in Abnormal Psychology

Carefully read the section in the textbook entitled “Changes in the Therapeutic Landscape”, which covers the topics of the drug revolution, managed health care, an increased appreciation for research, and technology-assisted therapy.

In this section we will consider a major contemporary issue that is not in the textbook: prescription privileges for psychologists. This is the trend that certain states and U.S. territories (New Mexico, Louisiana, and Guam were the first three) allow psychologists to prescribe psychotropic mediations such as Prozac if they go through the appropriate schooling and certification process. Table 1.1 contains some of the arguments for and against psychologist prescription privileges (from Gutierrez and Silk, 1998).

|

Pro's |

Con's |

|---|---|

|

Studies have shown that psychologists and psychiatrists are equally competent at diagnosing and prescribing. |

In the distant future psychologists may focus too much on prescribing and thus lose sight of talk therapy. |

|

Psychologists spend more time with clients and get to know them better, which can allow them to monitor meds more effectively. |

Medication may be less empowering than psychotherapy and patients may attribute change to an outside source rather than from something within themselves. |

|

Psychologists can more effectively treat clients with more severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar. |

Getting prescription privileges may place an added burden on an already overly long grad school curriculum. |

|

Clients in rural areas may have more access to providers who can prescribe medication (this is a reason why more remote places were the first to grant prescription privileges for psychologists). |

There are many people within the field of psychology who oppose prescription privileges so there is a lack of consensus among psychologists; thus, pursuing prescription privileges may create a divide within the field. |

Brainstorm Ideas

Think about these questions as you generate thoughts and ideas in preparation for the Lesson 1 Discussion Forum questions found at the end of the lesson.

- What are your general thoughts about prescription privileges for psychologists?

- Can you think of other pro's and con's that are not on the list?

Lesson Summary

One take away message from this lesson is that the concept of “abnormality” is highly diverse. You need to consider many different criteria and many different contextual factors when determining whether a behavior is “abnormal” or not. Also, there are many different ways of treating abnormal behavior of a clinical nature.

We’ll end this discussion of abnormality with one final distinction that you’ll need to know throughout the semester: the difference between “clinical” and “sub-clinical”. Sub-clinical or “normal” means that a person does not meet the formal criteria for a DSM-5 or ICD diagnosis; it’s possible for someone to be considered abnormal using various criteria from this chapter yet their issues can be sub-clinical in nature. Clinical means that an issue does meet a formal mental health diagnosis and is thus in need of treatment in some way. In Lesson 3 we will discuss certain assessment tools that are for a clinical population (such as mental health tests) and others that are for a sub-clinical population (such as personality and career tests). However, the next lesson involves key ethical and legal issues that all mental health professionals (and students) need to know.

Finally… beware of the “Medical Student Syndrome”! This is when you read through something like the DSM-5 and say, “Oh no that’s me! I have that!” Diagnosing yourself while taking this class can be very dangerous so please try to avoid doing so. However, feel free to diagnose people in your life like roommates, friends, or even pets. I like to bring the DSM-5 to family gatherings and then go through and check off the disorders that people have (just kidding, of course :p).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th Ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Benjamin, L.T., & Baker, D.B. (2004). From séance to science: A history of the profession of Psychology in America. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson. Berenbaum, H. (2013). Classification and psychopathology research. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 894-901.

- Berman, J.S., Miller, C., & Massman, P.J. (1985). Cognitive therapy versus systematic desensitization: Is one treatment superior? Psychological Bulletin, 97, 451-461.

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2016). Hepatitis C FAQs for health professionals. Retrieved May 13th, 2016 from http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2014). National Provider Index Database [Data file accessed on 6/10/2014]. Retrieved from http://nppes.vita-it.com/NPI_files.html

- Frank, J.D., & Frank, J.B. (1991). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Gutierrez, P.M., & Silk, K.R. (1998). Prescription privileges for psychologists: A review of the psychological literature. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 29, 213-222.

- Harvard Medical School (2007). Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV disorders by sex and cohort. Retrieved May 13th, 2016 from http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_Lifetime_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf

- Lambert, M.J. (2004). Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991) Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press.

- Prochaska, J. and DiClemente, C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change in smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 5, 390–395.

- Prochaska, J.O. & Norcross, J.C. (2007). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis. Belmont, CA: Thomson.

- Sue, D., Sue, D.W., & Sue, S. (2010). Understanding abnormal behavior (9th ed.). Boston: Wadsworth/Cengage.

- Sue, D., Sue, D.W., Sue, D., & Sue, S. (2016). Understanding abnormal behavior (11th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage.

- Viney, W., & King, B.D. (2003). A history of psychology: Ideas and context (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Wampold, B.E. (1997). Methodological problems in identifying efficacious psychotherapies. Psychotherapy Research, 7, 21-43.