PSYCH281:

Lesson 02: Introduction and History of I/O Psychology

Lesson Overview

This lesson will focus on the following topics:

- Defining Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Who we are and what’s in a name?

- The Scientist Practitioner model

- Comments on the History of the Field and Penn State’s Connection to I/O Psychology

- The importance of I/O psychology

Lesson Readings & Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Course Schedule.

Defining “I/O” Psychology

In your Introduction to Psychology course (i.e., PSYCH 100, the prerequisite for this course), you learned that psychology was the scientific study of thinking and behavior. Industrial and organizational (I/O) psychology is the application of psychology to workplace problems and phenomena (Blum & Naylor, 1968). Some examples of workplace problems an I/O psychologist might study or deal with in practice include the following:

- How do we select the right employees for the job?

- How do we train employees to ensure needed skills transfer to the job?

- How do we select the right leader for the organization?

- How can we better motivate employees?

Competencies of I/O Psychologists

If we look at guidelines provided by the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (the professional organization to which most I/O psychologists belong), we get a more comprehensive list of the competencies I/O psychologists tend to develop and share with the world of work.

|

|

Note: The list of the first 25 competencies above was taken from the guidelines for doctoral training. Descriptions of these topics can be found by going to the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology's PhD guidelines. Competencies marked with an * indicate competencies developed in master's programs as well as doctoral programs, and competencies marked with an ** indicate competencies considered additional or optional at the master's level.

"Penn State Proud" I/O Trivia:

The I/O Psychology program at Penn State has consistently ranked high among graduate programs across the country. According to a 2009 poll by U.S. News & World Report, Penn State ranked second in the nation.

Where Did the I and O Come From?

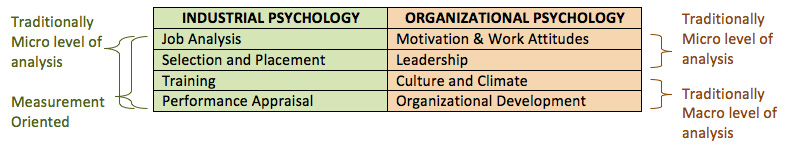

In the past, core competencies have been roughly categorized as either industrial psychology or organizational psychology (Katzell, 1992). The table below provides an example of where some of the above categories would be placed. In general, industrial psychology focuses on the measurement of job requirements and individuals' knowledge, skills, abilities, and performance so as to match individuals with suitable jobs. Organizational psychology is more theoretical and considers psychological processes such as motivation and work attitudes. Organizational psychologists also study phenomena that occur at a level higher than the individual, such as group and organizational climate as well as organizational change and development. Studying phenomena at these higher levels of analysis or focus is called macro research while studying phenomena that occur at an individual level is called micro research.

Scientist-Practitioner Model

As mentioned in your textbook, one goal of the field is to blend science and practice. We call this the scientist-practitioner model. Check out your textbook chapter for a definition of the scientist-practitioner model.

It should be noted that communicating between science and practice is difficult to do because the goals, loyalties, and jargon of those in academic (scientific) positions often differ from those of practitioners (Dunnette, 1990).

| - | Scientists | Practitioners |

|---|---|---|

| Loyalties | Publishers Academic departments | Managers CEOs |

| Goals | Rigorous science "Publish or perish" | Solutions to immediate problems Increase profits |

| Jargon/Language | Scientific | Bottom line (i.e., monetary) |

Despite these differences, members of the field strive to work together and communicate via annual conference meetings and research collaborations (Brice & Waung, 2001).

Brief History of the Field and the Penn State Connection

More "Penn State Proud" I/O Trivia

Figure 2.2 The photo above was taken from the PSU Psychology Clinic's website.

Figure 2.2 The photo above was taken from the PSU Psychology Clinic's website.

Penn State has a special connection to I/O psychology. How?

Bruce V. Moore is arguably one of the first individuals to receive a doctoral degree in the field. With his degree, the field began to become acknowledged as a separate program or subfield within psychology. Moore later became the first president of the division of the APA for industrial and organizational psychology.

Note: Moore also became the chair of the Department of Psychology at Penn State. In fact, the building housing the psychology department is still named Moore today.

In 2012, an addition and renovations of the original Moore Building began. Above is an artist's rendition of what the building will look like when completed.

Your textbook covers most important landmark events in the development of the field, so we will not review everything here.

Importance of I/O Psychology

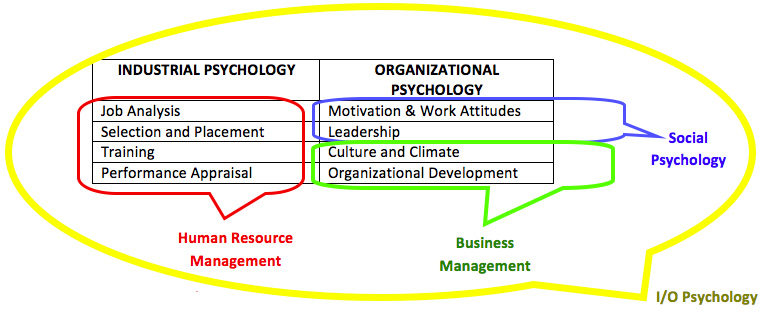

The focus of I/O psychology overlaps with other fields but also differs from them. While other disciplines study or apply programs and research similar to those studied and implemented by I/O psychologists, the range of topics studied and actively pursued by I/O psychologists is arguably larger, encompassing issues studied by members of the fields of human resource management (HRM), social psychology, and business management. If we take a look at the figure below, we can see how I/O psychology overlaps with other related disciplines.

Figure 2.3. I/O Psychology's Overlap With Other Disciplines

Although members of HRM, business management, and social psychology may study other topics in addition to those pointed out above, none of them focuses on the entire set of topics we'll be discussing in this course. For more information about these other disciplines, you can check out the websites of the major professional organizations in those fields (listed below under supplemental readings).

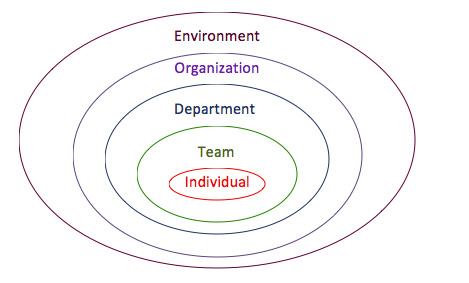

I/O psychology considers not only people, but also the context within which those people work. This focus on individuals is unique in an environment where management is primarily concerned with the success of the organization as a whole.

Figure 2.4.

Again, not all individuals in the field of I/O psychology can address these levels all at the same time in either their research or practice, but it is the goal of the field collectively to be informed about the entire picture above.

Furthermore, I/O psychology is grounded in science, focusing on testing and evaluation using quantitative methods. This is not the same as using simple intuition or trying new things until something works. Our methods are studied with scientific precision and backed by theory and statistics. We'll learn more about our methods of study in our next lesson.

Finally, there are many reasons for organizations to be interested now and in the future in social and psychological processes in order to better understand how their organizations and the people in them work and how to make their organizations more productive and competitive places. For example, companies are beginning to compete on a global scale more than ever before. Therefore, it's important to know how to motivate workers for ultimate productivity and efficiency. Another example is that many companies have an increasingly diverse workforce. Information about how to best manage the social and psychological complexity of working with members from diverse backgrounds is key to the success of these organizations.

References

Ash, R.A., & Edgell, S.L. (1975). A note on the reliability of the Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ). Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 765-766.

Blum, M.L., & Naylor , J.C. (1968). Industrial psychology: Its theoretical and social foundations. New York: Harper & Row.

Branick, M.T., & Levine, E.L. (2002). Job analysis: Methods, research, and applications for human resources. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Brice, T. S., & Waung, M. (2001). Is the science-practice gap shrinking? Some encouraging news from an analysis of SIOP programs. The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist, 38 (3), 2937.

Dunnette, M. D. (1990). Blending the science and practice of industrial and organizational psychology: Where are we and where are we going? In M. D. Dunnette and L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 1). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Katzell, R.A., & Austin, J.T. (1992). From then until now: Development of industrial-organizational psychology in the United States. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(6), 803-835.

Muchinsky, P.M., & Howes, S.S. (2019). Psychology applied to work: An introduction to ndustrial and organizational psychology. Twelfth Edition. Summerfield, NC: Hypergraphic Press.