Lesson 2: Introduction (Printer Friendly Format)

page 1 of 4

Lesson 2: Introduction

Before you begin…read Chapter 2 in the textbook and be sure to look over the Paper Assignment #1. Paper 1 is due at the end of this week.

Developing a Research Hypothesis

In your textbook a hypothesis is defined as, “a specific and falsifiable prediction regarding the relationship between or among two or more variables” We will return to the ideas of “specific” and “falsifiable” a little later. For now, the reason that I put this up here is to point out anyone can generate a hypothesis about any two or more variables.

We need to be specific about how we describe our variables. The textbook mentions the idea of predictor and outcome variables, and the idea of independent and dependent variables (commonly written as IV and DV). Let’s take an example and try some of these variable names on for size.

My two variables are: Walking Speed (in miles per hour) and Mood (an emotional state involving either positive (e.g. happy, excited) or negative (e.g. sad, angry) emotions). At this point I can generate several hypotheses related to these variables.

Hypothesis 1: People in positive moods will walk faster than people in negative moods.

Hypothesis 2: People who walk faster will experience more positive moods than will people who walk more slowly.

At this point you may be thinking, “Great, you said the same thing twice. That’s not very interesting.” In fact these hypotheses actually imply two different psychological processes. (Huh?) What I mean is that Hypothesis 1 implies that mood is influencing how fast people are walking. Mood is causing a change in walking speed. In this case, mood is the predictor variable and walking speed is the outcome variable. For Hypothesis 2 it’s implied that walking speed (now the predictor variable) actually influences mood (the outcome variable). More importantly, the implications for the processes at work are very different. For Hypothesis 1, it could be that happy people tend to expend more energy overall than do sad people, and this is causing them to walk faster. For Hypothesis 2, the act of physical exertion is implied to change people’s mood in a positive direction (exercise makes people happy, perhaps).

page 2 of 4

Developing a Research Hypothesis Continued

Hypothesis 3: There is a positive correlation between walking speed and mood.

What I’ve done now is provide a hypothesis that is much less specific. I’m saying that as walking speed increases, mood will become more positive. I’m also saying that a positive mood will be related to faster walking speed. In this case I’ve removed any predictions about the direction of causality and I’m only saying that these two variables will be related in a specific way (positively). It’s typically a good idea to think in terms of a predictor variable and an outcome variable because it adds specificity to the hypothesis. On the other hand, it’s perfectly plausible that the relationship between these two variables really does work both ways.

As your textbook points out we use the terms predictor and outcome variables mostly when we are talking about a correlational design. For our example this might mean measuring people’s mood and measuring how fast they walk. Another way to test a hypothesis is by using an experimental design. The key to doing that would be to assign one of my variables to be the predictor (independent) variable, and the other variable to be the outcome (dependent) variable. Instead of just measuring the predictor variable I want to create levels. (Huh?) For example, let’s say that I want to see if mood can cause a change in walking speed. I could put half of my participants into a negative mood and the other half of my participants into a positive mood (this is usually done by having people watch either very sad or very funny movies). My independent variable (IV) is mood. It has two levels; positive mood vs. negative mood. My dependent variable (DV) is walking speed. I can now compare how fast the “positive mood people” walked with how fast the “negative mood people” walked. If there is a difference in walking speed then it must have been caused by mood. We will be returning to these issues a lot during this course, but for now remember that Independent and Dependent variables go with experimental designs, and predictor and outcome variables go with correlational designs.

Go to Assignment 2 and fill out Part 1.

page 3 of 4

Initial stages in conducting scientific research

Getting Ideas

Before beginning a research project, you must determine what aspects of the topic you wish to focus on and refine these interests into a specific research design. For your final paper you will be creating an experimental design with two IVs and one DV. We’ve got a lot to cover before we get there, but in the meantime you should already be thinking about Paper 1 Assignment. Some of you probably already have an idea about your proposal, and some of you are probably struggling to come up with something. Here are a few of the ways that researchers go about developing new hypotheses.

You read in your lesson 2 textbook reading assignment about the Inductive and Deductive methods for idea development. To summarize, the Inductive method involves getting ideas about the relationships among variables by observing specific facts. With this method you are using facts to generate theories. The Deductive method is the process of using a theory to generate specific ideas that can be tested through research, in other words, using theory to examine the facts.

An Odd Example

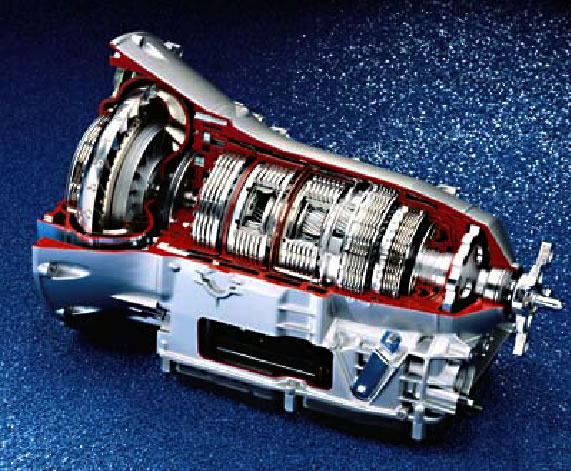

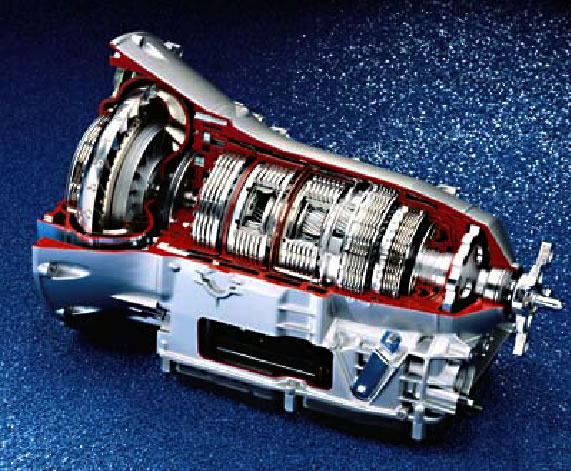

Imagine that on the first day of this course I told you that your final grade will depend on whether or not you can come up with a way to improve on the design of the thing pictured to the left. For those of you who didn’t immediately drop the course (and lodge a complaint with the university) what would you need to do first in order to complete this ridiculous task?

Imagine that on the first day of this course I told you that your final grade will depend on whether or not you can come up with a way to improve on the design of the thing pictured to the left. For those of you who didn’t immediately drop the course (and lodge a complaint with the university) what would you need to do first in order to complete this ridiculous task?

First you would need to figure out what that thing to the left actually is. It’s an automatic transmission for a car.

Next you would need to understand what people already know about these things (how do they work, how are they put together, which designs are most efficient, etc.).

Finally then you might be able to come up with a way to improve upon the design. This same sort of idea is actually taking place in this course. You are required to come up with a hypothesis that in some way improves upon what other psychologists have been working on for years. You shouldn’t expect to have the perfect idea right away.

A good researcher starts with a topic that is of interest, and then spends a great deal of time finding out what other people know about this topic. This knowledge can be found in a number of ways, but the most common is by conducting a literature search. You will be doing this for your first Lab, so I won’t go into the specifics now. What I will say is that understanding human behavior requires a lot of reading because thousands of researchers have published tens of thousands of articles over the past one hundred years. Don’t panic. You won’t be required to read thousands of articles, but you should expect to read a dozen or so.

page 4 of 4

Components of a Good Theory

So perhaps you have an idea. It could be based on your own observations of people (the inductive method), or perhaps it’s based on theories that you’ve heard about (the deductive method), or even more likely, it’s a little bit of both. How do we know if it’s a good or a bad hypothesis? (Your textbook covers this, so I’m going to be brief.)

Remember way back to the beginning of this lesson (I know, it seems like forever ago). I wrote out the definition of a hypothesis (“a specific and falsifiable prediction regarding the relationship between or among two or more variables”) and then told you that I’d come back to the specific and falsifiable part later. It’s later now, so hear goes. The textbook mentions three things that denote a good hypothesis. It should be general, parsimonious, and falsifiable. Let’s start with general and parsimonious, because these terms actually combine (sort of) to create the “specific” requirement from the definition. By saying that a hypothesis should be general I’m implying that it should apply to a wide variety of people and experiences. It’s not very useful to have a theory (or a hypothesis) that is only applicable on Tuesdays between 11:30 and 11:45am for left-handed people living on streets that have speed bumps. I’m being a bit facetious, but the idea is that a theory is much more useful if it applies to a greater population across a wider range of situations. So a theory that applies to people who are left-handed would be much more inclusive and useful. (By the way there are many theories in psychology related to handedness.) Parsimonious means without excess. When we talk about a parsimonious theory or hypothesis we are implying that the ideas are simple and straightforward. Imagine a hypothesis that required a long list of exceptions (“It is predicted that A will cause B, except on Tuesdays, or if the person is taller than five foot three inches and B might cause A on Thursdays after lunch…” Ok, I’m getting silly.) Combining the goal of being inclusive (being general) with the goal of being straightforward (parsimonious) a good researcher finds a balance related to specificity. Too specific, you’re probably not general enough. Too broad, then you probably will need to include too many exceptions, and thus violate the “keep it simple” idea.

Lastly, there is the notion that a good theory should be falsifiable. Here’s an example of a “bad” theory: “Eating ice cream is either healthy or it is unhealthy”. Well my theory is general and parsimonious, but it’s also completely useless. Why is it useless? Because it can never be wrong, and therefore although it can never be disproven it can’t help me to understand the world.

At this point you should complete Part 2 of the Assignment 2 Then go to the Lab folder and complete Lesson 2 Lab. After you have finished that, you should read over the requirements for your first paper, Paper Assignment #1. Paper 1 is due at the end of this week.

When you have finished with everything related to Lesson 2 you can move on and read the lesson 3 textbook reading assignment, and then read over the Lesson 3 Commentary.

Imagine that on the first day of this course I told you that your final grade will depend on whether or not you can come up with a way to improve on the design of the thing pictured to the left. For those of you who didn’t immediately drop the course (and lodge a complaint with the university) what would you need to do first in order to complete this ridiculous task?

Imagine that on the first day of this course I told you that your final grade will depend on whether or not you can come up with a way to improve on the design of the thing pictured to the left. For those of you who didn’t immediately drop the course (and lodge a complaint with the university) what would you need to do first in order to complete this ridiculous task?