PSYCH476:

Lesson 1: Introduction to Normal and Abnormal Behavior in Children and Adolescents

Introduction

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Our history shows that, until recently, we have failed to understand the unique mental health needs of children and adolescents. This misunderstanding led to some faulty conclusions that further jeopardized the well-being of these individuals. For example, a lack of understanding led many to believe that children with behavioral and emotional problems just needed more discipline to overcome their difficulties. Centuries of abuse resulted from misunderstandings such as this. Fortunately, recent decades have offered much promise. Through research and inquiry, professionals across many disciplines (e.g., psychology, education, medicine) have increased our understanding of child development. This understanding, combined with advances in knowledge about the causes of mental illness, has aided in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of psychological problems in the early years of life. As is often the case, new understanding leads to additional questions – offering further hope and excitement to the study and treatment of the problems of young people.

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to:

- demonstrate an understanding of the history of abnormal child psychology

- define abnormal behavior in children and adolescents

- demonstrate an understanding of the unique challenges involved in understanding abnormality in children and adolescents

- recognize specific factors that may place children and adolescents at risk for mental disorders, as well as important protective factors

Lesson Readings & Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Course Schedule.

Historical Perspectives

Over the past several centuries there have been dramatic changes in how children and adolescents with psychological problems are viewed and treated. Consider some of these early views:

Early Views

Ancient Greece/Rome

- Those with physical or mental handicaps (of all ages) were an economic burden and social embarrassment. The fate of these individuals was to be ridiculed, abandoned, or put to death (French, 1977).

Prior to the 18th Century

- Children’s mental health problems were largely ignored.

- Abnormal behaviors were attributed to children’s uncivilized and provocative nature – influenced largely by religious views at that time.

- Children were subjected to harsh treatment due to beliefs that they would die, were possessed, or were parents’ property. For example, the Massachusetts Stubborn Child Act of 1654 permitted parents to put “stubborn” children to death for misbehaving. Although no children were known to be put to death, the law protected parents who kept children with severe disabilities in cages and cellars (Donohue, Herson, & Ammerman, 2000).

End of 18th Century through the 19th Century

-

Awareness and concern for children with psychological problems increases as a result of:

- A move away from religious explanations for childhood problems toward a disease model which emphasized more humane treatment.

- Increased emphasis on teaching, training, and supporting children.

- Interest in abnormal child behavior has continued to improve since this time.

Important Early Figures

Click on the named tabs to learn about each individual.

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

John Locke (English philosopher and physician):

Advanced the view that children should be raised with thought and care, not with the harsh treatment common during his time. He also was among the first to see the importance of education and training for children.

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Jean-Marc Itard (French physician):

Engaged in one of the first documented efforts to work with a child with special needs (Victor of Aveyron). This work sparked other efforts to help children with developmental, psychological, and behavioral problems.

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Dorothea Dix (American activist):

Among a vast array of advocacy efforts, she helped establish humane mental hospitals for the treatment of youths.

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Leta Hollingworth (American psychologist):

Helped to distinguish between children with intellectual impairments and those with serious emotional and behavioral problems. This distinction was important for treatment of these problems.

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Benjamin Rush (American physician):

Helped begin to distinguish between the mental problems of children and adults. His views further advanced the humane treatment of children as well as exploration into the causes of psychological problems.

Important 19th and 20th Century Events

- 1896: First child clinic in the United States was established at the University of Pennsylvania by Lightner Witmer.

- 1905: Alfred Binet and Theophil Simon developed the first intelligence tests to identify children who could benefit from special educational efforts.

- 1909: G. Stanley Hall invited Sigmund Freud to lecture on psychoanalysis at Clark University. Despite concern about some of Freud’s theory, he advanced the idea that events during early childhood can have a significant impact on development.

- 1909: William Healy and Grace Fernald established the Juvenile Psychopathic Institute in Chicago, which would become the model of the child guidance clinics.

- 1911: The Yale Clinic of Child Development was established for child development research under the guidance of Arnold Gesell.

- 1913: John B. Watson introduced behaviorism in his essay Psychology as a Behaviorist Views It. The behavioral view has been influential in the understanding and treatment of childhood problems.

- 1917: William Healy and Augusta Bronner established the Judge Baker Guidance Center in Boston. The emphasis at this center was on diagnostic studies and treatment recommendations for children brought to juvenile court.

- 1922: The National Committee on Mental Hygiene and the Commonwealth Fund initiated a demonstration program of child guidance clinics.

- 1928-1929: Longitudinal studies of child development began at Berkeley and Fels Research Institute.

- 1935: Leo Kanner authored Child Psychiatry, the first child psychiatry text published in the United States.

Defining and Identifying Abnormal Behavior

Michael is a 5-year-old boy who was recently kicked out of his preschool program. Along with his failure to engage in the classroom (e.g., sat on the floor and stared, refused to talk), he hit any child who came near him or touched him. If his teachers corrected him or insisted that he participate, Michael cried, yelled, and banged his arms and head on the floor. Similar behaviors were occurring at home. Michael rarely talked, showed little emotion other than anger, rocked back and forth when sitting, and slept terribly.

Based on this definition and criteria, we could conclude that Michael’s behavior meets the general criteria for a psychological disorder. However, because he is a child, there are some additional factors that we should consider.

Competence

The ability to navigate social, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral tasks within one’s environment. A part of evaluating competence involves understanding cultural factors (e.g., beliefs regarding a child’s role) that may influence evaluations of competence.

Developmental Tasks

Knowledge of developmental tasks, such as conduct and academic skills, is important to making judgments regarding impairments. For example, expectations for how long a 2-year-old can sit still and focus on a task are much different than those for a 6-year-old child.

Developmental Pathways

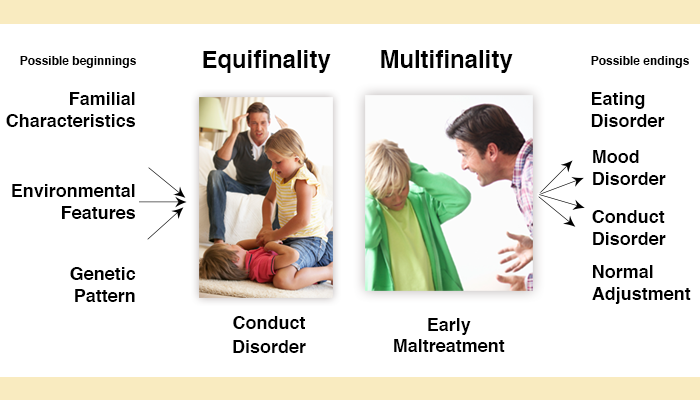

The timing and sequence of behaviors and events are interactive over time and may lead to similar or dissimilar outcomes depending on a variety of factors (e.g., individual personality characteristics). Two examples of developmental pathways can help us understand the development of psychological problems.

Multifinality and Equifinality

Multifinality: Various outcomes may result from similar beginnings. In this scenario, an early history of child maltreatment (i.e., a similar early event) impacts different individuals in different ways. Some may go on to develop a psychological problem while others may not experience any impact on later adjustment.

Equifinality: Similar outcomes result from different early experiences. In this scenario, a range of early experiences may result in the development of a common psychological problem.

Risk and Resilience

Eddie grew up in the inner-city of Chicago, raised by a single mother who worked two jobs that still couldn’t make ends meet. His father went to prison when Eddie was 8 years old, ending a long history of abuse. Eddie was bullied in elementary school, but began to find acceptance during his adolescence with a group of friends who regularly found themselves in trouble with the police. After barely completing high school, Eddie went to work at an auto repair shop where he found a mentor in a man named Mr. Sullivan. Mr. Sullivan saw promise in Eddie’s abilities and encouraged him to pursue specialized training in automotive repair. Today, Eddie owns a successful auto repair shop, is married, and has two young boys.

Why do some children who have been maltreated (or exposed to other adverse events) go on to experience psychological problems and other troubles while others seem to succeed without these setbacks? Though the answer is not straightforward, research examining risk and protective factors can help answer this question. Risk factors are variables that precede a negative outcome and increase the chances that the outcome will occur. Some examples of risk factors include high levels of family conflict, peer rejection, and prenatal complications. On the other hand, protective factors are personal or situational variables that reduce the chances of a child developing a psychological disorder. Examples include good problem solving skills, supportive family relationships, and high achievement motivation. Risk and protective factors can be related to characteristics of the child, his/her family, and the community.

The term resilience is frequently used to describe why Eddie, from our example above, overcame adversity, while others in very similar circumstances might not. Resilience can be defined by a relatively positive outcome in the face of significant adversity or traumatic experiences (Luthar, 2006). It is important to understand that resilience is not a universal characteristic that is applicable to all situations. Rather, interactions between risk and protective factors as well as the circumstances of a situation likely explain differences in resilience across time, situations, and individuals.

A Current Picture of Mental Health Problems

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Surveys conducted in the United States find that approximately one in eight children have a mental health problem that has a significant impact on their daily functioning (Costello, Egger, & Angold, 2005). Perhaps even more alarming is the fact that fewer than 10% of these children are receiving proper services to address these problems (Costello et al., 2005). A large part of the explanation for this lack of intervention is related to a lack of understanding of psychological problems and limited access to resources. Another issue involves the fact that these problems are coinciding with ongoing developmental changes. It is sometimes difficult for adults to determine which problems require professional attention and which are a part of the normal course of development. Making this determination requires a strong understanding of child development – being able to distinguish normal characteristics and behaviors from those that are abnormal.

In addition to general statistics about the prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents, recent research has highlighted characteristics that place certain groups of children at increased risk for developing mental health problems and some key factors that influence rates and expression of these disorders. We know, for example, that children from disadvantaged families, who receive inadequate child care, or are born to parents with mental illness or substance abuse problems are more likely to experience mental health problems (Davis, Glynn, Waffarn, & Sandman, 2011; Mellin, 2010; Pollak et al., 2010; Razza, Martin, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010). We also know that factors, such as a child’s sex and cultural background, influence the expression and recognition of psychological disorders. For example, cultural beliefs are likely to influence the meaning given to certain behaviors as well as the response to them. It is important to recognize and consider the potential influence of these factors.

Approximately 20% of children who experience serious and chronic psychological problems will continue to face significant difficulties throughout their lives (Costello & Angold, 2006). These problems are most severe if these problems are unrecognized and untreated for extended periods of time.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition). Washington, DC: Author.

Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2006). Developmental epidemiology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theory and method. (2nd ed., pp. 41-75). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Costello, E. J., Egger, H., & Angold, A. (2005). 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 972-986. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000172552.41596.6f

Davis, E. P., Glynn, L. M., Waffarn, F., & Sandman, C. A. (2011). Prenatal maternal stress programs infant stress regulation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 119-129. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02314.x

Donohue, B., Hersen, M., & Ammerman, R. T. (2000). Historical overview. In M. Hersen & R Ammerman (Eds.), Abnormal child psychology (2nd ed., pp. 3-14). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

French, V. (1977). History of the child’s influence: Ancient Mediterranean civilizations. In R. Q. Bell & L. V. Harper (Eds.), Child effects on adults (pp. 3-29). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology. Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Mash, E. J., & Wolfe, D. A. (2013). Abnormal Child Psychology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Mellin, E. A. (2010). Childre of families affected by a parental mental illness. In M. H. Guindon (Ed.), Self-esteem across the lifespan: Issues and interventions (pp. 79-90). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Pollak, S. D., Nelson, C. A., Schlaak, M. F., Roeber, B. J., Wewerka, S. S., Wiik, K. L., … Gunnar, M. R. (2010). Neurodevelopmental effects of early deprivation in postinstitutionalized children. Child Development, 81, 224-236. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01391.x

Razza, R. A., Martin, A., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2010). Associations among family environments, sustained attention, and school readiness for low-income children. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1528-1542. doi:10.1037/a0020389