PSYCH485:

Lesson 1: Introduction to Leadership

Lesson 1 Introduction

Leadership is one of those concepts that we all have some familiarity with, but have likely never given a lot of thought to what it is. Before you read any further, take a minute to think about what leadership means to you. How do you define leadership? How would you describe a good leader?

Mini Activity

Take a minute to write down your definition of leadership. After you have done this, ask a friend or relative to define leadership. You will probably find that your definitions are different.

Imagine if you were to stop and ask busy people on the street what leadership meant to then. What sorts of answers do you think you might get? Well, let’s watch this video and find out:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SPEAKER: What does the word "leadership" mean for you?

SPEAKER: Yeah, good question.

SPEAKER: Difficult one.

SPEAKER: Leadership is motivating others in the group.

SPEAKER: It's the one who can take control.

SPEAKER: And guide other people in a direction is like the main idea.

SPEAKER: Inspiration, direction, encouragement. But someone can be a leader of something, even if they're not technically in charge of it.

SPEAKER: But it can also be inclusive, like getting people to have their own opinions. But overall, it's to control the given situation, even though it's allowing people to have individual thought within that.

SPEAKER: It's more about commanding, I think, someone taking over in a time when pressurized and in a job where a lot's going on and someone needs to take control of the situation.

SPEAKER: Leadership is controlling a group of people, in terms of a team.

SPEAKER: [LAUGHS] I think I haven't a clue.

SPEAKER: You have to be someone very strong as a personality, able to see what people need and what people strive for, and help them to achieve this.

SPEAKER: Leadership is being able to inspire people to do what you think is the right thing for them to do, to be able to give them that motivation and encouragement to get the job done.

SPEAKER: Keeping people informed, obviously making the correct decisions.

SPEAKER: A place that's well run, good top-down management, something that you have respect for.

Were you answers to the questions above similar? Different?

Take note of what images have popped into your mind as you have been reading this commentary and watching the video. Maybe you envisioned a coach in a sports teams, a teacher classroom, a presidential candidate or other political or military figure, or maybe you thought about people you have worked with.

Leadership is a complex phenomenon, as you will see throughout this semester. There are many different definitions of leadership and many different approaches to study leadership. In this class we will learn about a variety of these approaches.

What Will We Learn in this Lesson?

At the end of this lesson you will be able to:

- Differentiate between theories and maxims

- Differentiate between trait leadership and process leadership

- Understand the differences between assigned and emergent leadership

- Explain the similarities and differences between leadership and management

- Be familiar with leaders, followers, and situations, and how they interact

- Be able to briefly explain how to assess leadership

Before we jump in, it’s important to start with a discussion about the need for psychological safety as we learn together in this course. As you might suspect and saw briefly in the video above, people’s views on the topic of leadership and opinions about various leaders can vary greatly. Therefore, it’s important that we establish some principles for how we will manage disagreement and maintain a learning environment in this course.

Lesson Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Course Schedule.

Psychological Safety

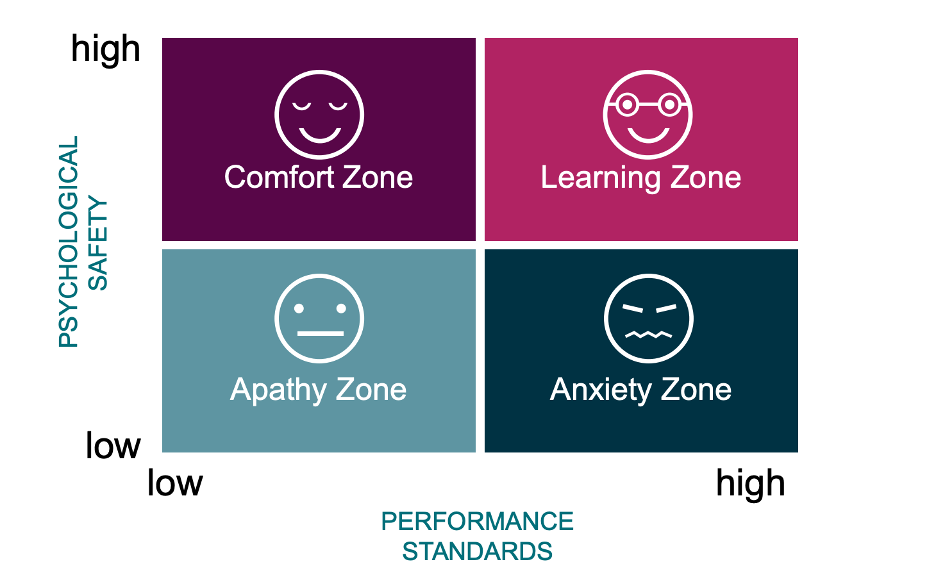

In this course, as with most courses here at Penn State, we are ultimately most interested in creating an experience that maximizes learning. And, research suggests that we do that best when we both (a) challenge students and (b) provide psychological safety as Figure 1.1 indicates (i.e., we are striving for the upper right quadrant).

High performance standards is pretty self-explanatory. In this course, for example, you are challenged to complete a number of different types of assessments to demonstrate learning. Psychological safety, on the other hand is a concept you may not be familiar with. In short, psychological safety is a feeling that one can speak up, change one’s mind, and discuss material without a fear of being reproached or punished by others (Edmondson, 2018).

You might be wondering why we are talking about this in a course on leadership. Well, as it turns out, this concept has been central to research on effectively leading teams. Check out the video below to learn about how research at places, like Google, Pixar, etc. are embracing this idea of psychological safety, and learn more about this from one of the main researchers in this area herself, Dr. Amy Edmondson:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

TREVOR RAGAN: In this package is the first magazine that I've purchased maybe this century. But it's a New York Times magazine from 2016, and in this issue there's an article that has sent me down one of the most exciting rabbit holes I've been down in a long time. I cannot wait to share it with you.

Here we go. "New research reveals surprising truths about why some teams thrive and others falter." This is an overview of a research project that Google did a few years ago called Project Aristotle.

SPEAKER 1: Well, Google has been working for more than four years now to figure out exactly how to best put together successful teams. The results so far are fascinating.

[STATIC]

TREVOR RAGAN: The premise of this study is brilliant. Google's basically like, OK, we have a bunch of teams within our organization. We have a bunch of information about the people on the teams. Let's study this to see if we can figure out what makes the best teams.

Step 1, find out each team's effectiveness. They measure this in four ways. An executive evaluates the team, a team leader evaluates the team, the team members evaluate the team, and then they have the concrete numbers like sales and different outcomes. All this determines how the teams perform, and then they compare that with the information about the people. Where they're from, their age, their skill set, even their personality types. And through years of collecting and analyzing all this data, they found--

[SILENCE]

--nothing.

SPEAKER 2: I hope you're hungry-- for nothing.

TREVOR RAGAN: This quote from the article, it sums it up. "We had lots of data, but there was nothing showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The 'who' part of the equation didn't seem to matter."

After all of these dead ends, they stumbled upon the work of a researcher from Harvard named Amy Edmondson that had the solution to their problem. Amy Edmondson and her team had been studying teamwork for years, and they actually found one specific variable that they thought was the most important. And through lots and lots of work, they found a way to measure this variable.

So Google takes Amy Edmondson's discovery, her variable and her assessment, and plug it into their data. Everything falls into place. It wasn't about the makeup of the team. It's how the team interacts.

Teams that scored higher on this assessment outperform the teams that scored lower on all four of those measures that we mentioned earlier. They make more money, they learn more, they perform better, score higher on the evaluations. So big picture, they discovered that this variable was the key for better group learning and better group performance.

[SWOOPING]

At virtually the same time that Project Aristotle is happening, there's an author, a journalist named Daniel Coyle traveling the world, researching for his new book The Culture Code. He visits a bunch of amazing groups and organizations like Pixar, the San Antonio Spurs, Navy SEALs. And after this long and in-depth journey, what did he find?

DANIEL COYLE: The language we use around culture is kind of hilarious, because it's like, oh, I just get that vibe. It's just got that soft-- that feel, that soft skill that they have. Well, beneath that soft vibe is a really hard science that's totally fascinating. And so that's where I went. And you quickly light upon the work of Amy Edmondson at Harvard.

TREVOR RAGAN: Google and Daniel Coyle weren't aware of one another, and they were going on very different journeys, but they land in the same place on the same topic on the same person, Amy Edmondson.

AMY EDMONDSON: I'm Amy Edmondson, and I'm a professor at Harvard Business School. I have been doing research broadly in the field of leadership and organizational behavior for a long time.

TREVOR RAGAN: Amy is a prolific researcher, and is most well known for her work on psychological safety. Now, she didn't invent the term, but she's on the cutting edge of what it is and how it plays out in different groups. Remember Project Aristotle from Google?

SPEAKER 3: So what we learned is that there are a few common themes that really separate the most effective teams at Google from the rest. But by far, the most important thing is a sense of psychological safety on the team.

AMY EDMONDSON: Basically, my interest, like yours, was learning. And I thought, if you were going to be able to learn, you've got to learn from mistakes. You've got to be able to speak up. You've got to ask for help. Like, if you're going to be able to learn, you've got to feel psychologically safe.

TREVOR RAGAN: Whenever I talk to a researcher, I try to focus on three big things. What is this? Why does this matter? How do we use it? So let's work through these three categories with Amy's help.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So the core idea with psychological safety is it's a feeling that we can be ourselves, that we can ask questions, that we can take risks, we can ask for help, that it is OK to do those things in this group. So in Amy Edmondson's great book, The Fearless Organization, she talks about some of the questions on that survey that measure psychological safety.

If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you. Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues. People on this team sometimes reject others for being different. It is safe to take a risk on this team. It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help. My unique skills and talents are valued and utilized. So if you kind of reflect on those questions, you recognize times where we've felt these things and maybe other times we haven't.

It's also worth taking a second and being clear on what psychological safety is not. It's not about lowering standards. It's not about being fake nice. It's not about brushing problems and tough challenges under the rug. In fact, when I talked to Amy, she said it's really the opposite.

AMY EDMONDSON: Are you asking me to relax our standards? And in my view, again, it's almost exactly the opposite there too, because my argument would be in order to achieve high standards, you need psychological safety. You need people to speak up when they're not sure. You need people to take risks that are smart, that they've thought about, oh, this might work. It's like the soil. The soil has to be healthy soil.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

TREVOR RAGAN: I did some digging, and I found all sorts of studies that look at this from all sorts of different angles. But if you go through them, they're all kind of saying the same thing. Psychological safety really matters, especially if we're talking about group learning and group performance.

And big picture, I think it's pretty simple. If we don't feel safe, we're probably not going to do the things that help us grow. We're probably not going to take smart risks. We're probably not going to seek out challenge, probably not going to learn from mistakes, probably not going to ask questions and ask for feedback.

And if the members of the team are avoiding the things that help us grow, it's really hard to learn. And if we're not learning, it's hard to perform well. One of the best summaries of why psychological safety matters is one of Amy's original papers. This is kind of how she first stumbled into psychological safety.

AMY EDMONDSON: I set out to ask a very simple question, which was, do better health care teams-- so teams with better teamwork, better interpersonal relations, better leadership-- do they make fewer medication errors?

TREVOR RAGAN: OK. So here's how they set up this study. They have access to eight teams that are spread across a couple hospitals, a team of physicians and trained nurse investigators. Their job is to track these teams for six months, and they determine the amount of errors each team makes.

And meanwhile, Amy gives each team what they called the team diagnostic survey. So this is before Amy used the label psychological safety, but it was measuring similar things. So the investigators and physicians determined the error rate, and Amy's diagnostic survey gives us a teamwork score. The hypothesis going in, like Amy said, was simple. Well, probably the better teams are going to make fewer errors.

But at the end of the study when they ran the numbers, something really weird happened. The better teams, the teams that scored better on the diagnostic survey, made more mistakes than the teams that scored the worst on the survey.

MICHAEL CERA: Yeah. Wait, what?

AMY EDMONDSON: And of course, after the initial shock, I thought, you know, something's wrong here. Like, this just-- this can't be right, knowing what I knew about the care process. So I stopped to think about it for a while, and maybe they aren't making more mistakes. Maybe they're more able and willing to talk about them.

[SWOOP]

TREVOR RAGAN: So this wasn't actually about which group was making the most mistakes. No. It was which group was reporting the most mistakes. The teams-- the better teams report more mistakes.

Now, this is true in hospitals, but this is true for all of us, no matter who we are, what we do. Owning mistakes, reporting mistakes, and reflecting on those mistakes, that is learning in a nutshell. That's how we grow from a setback. That's how we grow from an error. And if we're not owning them, if we're not reporting them, we can't reflect on them, we can't fix them.

The better teams report more mistakes. They're more likely to grow from them. And in this case, that means they're saving lives. And the groups that don't feel safe to own them and report them, not only are they missing out on opportunities to grow, there's literally lives at stake.

So we've hammered home what psychological safety is, and we've spent a ton of time on why it matters. But now we need to get into the most important piece.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

How do we actually build it? The studies, the book, they outline a lot of effective strategies that can improve psychological safety. For the rest of our conversation, I actually only want to talk about one. Modeling vulnerability builds psychological safety. And once you understand that simple equation, you see it everywhere.

We've all been in a meeting or at a presentation. They ask for questions. What happens? Usually crickets. But after some awkward silence, one person raises their hand. What happens next? 20 people raise their hand. One courageous act, one person being vulnerable and asking a question creates a safer climate for others to do the same.

AMY EDMONDSON: Each and every one of us can show up at work and make a difference in terms of creating the healthy learning climate in our team or with our colleagues. Just how I-- just how I show up actually matters. It can have a profound impact on just the few people around me.

TREVOR RAGAN: One of my favorite leaders and learners is Karch Kiraly. You might have heard of him. He's the head coach of the US Olympic women's volleyball team. And he's famous for setting up lots of one-on-one meetings with his players. And at the end of every meeting, he looks them in the eye and asks the same question. How can I be better for you?

Now, if you think about it, that question will probably lead to some powerful conversations, and he'll get some good feedback. But now with our knowledge of psychological safety, I hope you see what he's really doing is modeling.

Imagine you play for him, and every time he meets with you, he's asking you for feedback. Hey, how can I be better for you? It is now safer for you to ask him for feedback someday.

We can use a similar strategy. What are the actions that you want to see more of from the people around you? Find ways of putting those actions on display.

A school I work with did a project they called the Anti-Talent Show. Every student, every teacher picks something that they can't do. They get to practice it for two weeks. They hold the Anti-Talent Show. Some people learn to ride skateboards, juggle, recite poetry, paint.

I got to visit the school after they completed the project. And I asked some of the students, what was your favorite part of the Anti-Talent Show. One student raised her hand, and she goes, the best part of the Anti-Talent Show for me is that I got to see my teacher struggle, and that helped me understand it's OK for me to struggle too.

Wow. So modeling in this scenario was not just the teacher showing the student how to ride a skateboard. No. It was something bigger and more vulnerable. The teacher was modeling the learning process, the willingness to try something new, to make a mistake, to struggle. That created an environment where it was safer for the students to do the same.

And think about how powerful that can be. When we choose to take action, we improve the psychological safety within the group, but that also encourages more action. That can compound, and that's how you build a better learning environment from the ground up.

If you're interested in learning more about psychological safety, we'll put some links below. If you're in an environment that feels psychologically safe but you're still not taking action, I think my TEDx Talk on fear would be a great resource for you. We'll link that up as well. The last thing I want to say is a huge thank you to Amy Edmondson. You rule.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

If you liked this video, check out the article reflecting it - Better Leadership & Learning: A Guide to Psychological Safety.

So, what does this mean for us in this course?

- Expect moments of discomfort

Remember, we want to be stretching our knowledge and learning in this course. That means we will not always be comfortable and we may interact with some content, comments, students, and even an instructor and possibly a teaching assistant we disagree with at times. Remember that it’s okay to feel some discomfort or frustration while you learn new information and perspectives. IF the level of discomfort creates a barrier to learning, please reach out to your instructor (see point 4 below).

- Practice being a little vulnerable

It’s not always easy to speak our mind. We often worry about being seen as ignorant or bad. But, holding back in those moments often causes us to miss opportunities to learn and grow. So, practice being vulnerable. For example, ask a question even if you worry someone may find it silly.

- Give fellow students and your instructor the ‘benefit of the doubt’

Remember, that your fellow student and your instructor may be practicing vulnerability. If you read something that someone wrote or listened to something another student, instructor, or teaching assistant said and it does not sit well with you, give it a minute. Remind yourself that the other person likely did not have any ill-intent.

- Speak up if your discomfort persists, so everyone can have a chance to learn and grow

Often, we share information and ideas without realizing how those thoughts affect others. Hearing another person’s reaction allows us to visit our thoughts again from a new perspective. It’s allows learning to happen.

More importantly, there may be times when someone makes a mistake. Perhaps they chose their words quickly or poorly.

If you have any concerns about the course content, teaching assistant or instructor’s announcements or feedback, please contact the instructor. If the concern you have is with another student, and you do not feel comfortable discussing the concern with that student, please contact your instructor to discuss how you might proceed.

- Do NOT share quotes from class, Canvas, videos outside of class – because context matters!

As we explore this topic of leadership and examine how the research we are learning applies to different leaders, it’s possible you may say or read something that surprises you. For example, a team in the course may take on the challenge of examining a controversial leader. It would not be fair to those team members, your instructor, this course, nor this institution to take a quote or clip from their work and share it outside this course where it could raise concerns of others that are not experiencing the full context of this learning experience.

In addition, you will be asked from week to week to share examples applying the course material to your life and work experience. You will never be asked in this course to share highly personal information or disclose company secrets; all discussions will focus on leadership issues. That said, all students should feel free to share their real life work experiences here without concern that their words could be used against them in the current or future work place. It is also acceptable to change the names of people in any scenarios you choose to share from your personal experience for the sake of confidentiality.

For all the reasons mentioned above, it is important that we do NOT share course material in ANY way outside this course. This is true for everyone. Your instructor will also not share your work or writing outside this course (i.e., your work in the course is not being collected for research nor publication; all assessments are focused on helping you learn and/or assessing what you have learned. In the event that your work is exceptional, and the instructor would like to consider using it as an example for other students, you will be formally asked if that is okay and whether or not you would like to be identified with that work.

In your written assignment this week, you will be asked to indicate your agreement with the points above. If you have any questions about this at all, please contact your instructor as soon as possible.

Our Approach to Leadership in this Course

In this course, we will study both the science and practice of leadership. We will focus most on the theoretical and empirical perspectives from the field of psychology. But, from time to time will be bringing in ideas from business and management as well as other fields such as sociology, biology, and anthropology.

How does this differ from other potential approaches to leadership? There are a lot of books written on the topic of leadership that approach the topic from one leader’s personal experience. While those maxims and snapshots can be valuable, particularly when business enters a new age (such as the current advances in artificial intelligence) and little research is available, individual cases do not present a reliable picture. And, reliability is necessary for validity.

Certain questions can never be verified as the maxims (unlike theories) are not truly testable. For instance, was it that Bill Gates was a great leader to make Microsoft one of the largest and most profitable corporations in history? Or was it that the timing was right that people were ready for personal computers? Or was it that he had a fantastic work force? All of these explanations have been given as possibilities for the success of Microsoft, but we often attribute the success to Bill Gates because of the personal leadership maxim that he espouses, not to mention that it is much easier to focus on a single individual rather than look at every single factor. But what happens when those maxims are applied to another organization? Very rarely do they actually improve the organization. More often than not, they have no effect at all, and in some cases they actually have a negative effect because the ideas do not fit the organizational culture.

As a result, we will largely avoid leadership maxims and focus instead on psychological theories. Psychological theories are designed to not only explain phenomena, but also allow the scientific collection of data to support or potentially falsify the theory. A psychologist studying leadership may use a leader’s maxim as a starting point to creating a theory, but it is simply that; early idea generation, not the whole story.

Definition of Leadership

Northouse (2013) defines leadership as a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal. Let’s break this down…

- Leadership is a process

By saying that leadership is a process, we are saying that leadership is not a characteristic of the leader (such as being authoritative), but is an event that occurs between the leader and his/her followers. Leadership is not a one-way event, but an interactive event. Leadership involves something happening as a result of the interaction between leaders and followers.

- Leadership involves influence

The ability to influence others is called power. In the reading assigned, you will learn that leaders have many different types of power (i.e., ways of influences others). As you read about these different bases of power, you will start to appreciate how diverse leaders can be.

- Leadership occurs within a group context

If you started searching for leaders in different contexts, like sports, you might find that people sometimes use the word leader to mean ‘one of the best.’ That is not the approach we are taking in our study of leadership. Leadership, as we will learn, requires followers. Leaders may initiate the relationship with followers and hold more (and various type of power), but leaders need and are not better than followers.

The role of followers has not always been appreciated. When we read history books, the role of leaders is emphasized, but we don’t usually learn about followers. Followers’ expectations, personality traits, ability levels, and motivation affect the leadership process. Workers who share a leader’s goals and values and who feel rewarded for performing a job well might be more likely to work extra hours on a project than those whose motivation is only monetary. The number of followers can also have important implications. A manager who has six individuals working for him or her can spend more time with each individual than a manager with sixty subordinates.

The situation or context is also important in the process of leadership. We could know everything about a leader and the followers, but we need to know how leaders and followers interact in certain situations. The situation is the most ambiguous aspect of leadership since it can refer to anything from the task the group is working on to a broad context such as the work setting.

- Leadership involves goal attainment

Leaders are not just hanging out with followers to have a good time. The nature of the relationship is more pragmatic, often involving effort towards a particular “end.”

Note that Northouse’s (2013) definition here includes the “means” (part 1) and the “end” (part 4). This is important, because ignoring either could change our thinking drastically. For example, if you felt that the end was all that was important, you might entertain leaders using immoral means to achieve that end. Or, you might ignore a lot of potentially great leaders that did not accomplish their goals for reasons outside their control.

The greater implication here is that by including both the means and ends, we assume that leadership has a moral component. The ends or goals should involve increasing the common good. And, the means should be those that create as minimal harm as possible.

We may discuss people called leaders that have perpetrated immoral acts for the sake of learning in this course (e.g., Hitler), but it’s important to point out that by our definition, they are not really leaders.

Sources of Leader Power

The 2nd element in our definition above states that leadership is about influence. So, let’s look at what that can mean.

First, what comes to mind when you think of power? Is power a good thing or a bad thing? Do leaders have power over others? When you think of leadership, you may automatically picture a person that has power.

Power is the capacity to produce effects on others (House, 1984), or the potential to influence others (Bass, 1990). Influence is the change in a target agent’s attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors as a result of influence tactics. Influence tactics are one person’s actual behaviors designed to change another person’s attitudes, beliefs, values, or behaviors. These are the behaviors exhibited by one person to influence another. They range from emotional appeals, to the exchange of favors, to threats. People with more power will probably use a wider range of influence tactics than individuals with little power. Keep in mind that both leaders and followers can use influence tactics.

In sum, power is the capacity to cause change and influence is the degree of actual change in attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors. This means that influence can be measured by the behaviors or attitudes of followers.

Example of Power

Let’s use an example to clarify all of this. Your instructor for this course is a leader. Your instructor has power over you in that he/she/they have the capacity to cause change in your work patterns (since he/she/they can decide your grade). However, we do not see that influence over you until you actually make corrections to your assignment (change your behavior) in order to obtain a higher grade on your work.

Where do leaders get their power? Do leaders just have their power, or do they get it from their followers? Traditionally (as you will see in upcoming lessons), power has been seen as something that a leader possesses. However, power is a function of the leader, the followers, and the situation. Leaders can potentially influence the behaviors and attitudes of their followers. But followers can also affect the behavior and attitudes of the leader.

Many things, including the arrangement of office furniture, hanging diplomas on a wall, and even clothing can affect one’s power. When we want to be seen as more powerful, we often dress in suits. This is because we are judged to have more power dressed in a suit than in jeans and a t-shirt. A classic study by Bickman (1974) shows this effect. In this study, people walking along a sidewalk were stopped by a person dressed in regular clothes or a security guard uniform. They were asked to give a dime to a guy parked at a meter who had no change. When the request was given by someone in regular clothes, less than half of the participants actually gave the man change. However, when the request was given by the person dressed as a security guard, over 90% gave the man change.

How Can Power Influence Others?

French and Raven (1959) came up with five ways that individuals can influence others. It is important that we understand these bases of power, which are: expert power, referent power, legitimate power, reward power, and coercive power.

Expert power is primarily a function of the leader. It is the power of knowledge. An expert in a particular area can influence other people. In psychology there are certain people that are seen as experts in specific topics. For instance, a leading theorist in intergroup conflict is Felicia Pratto. Thus, Dr. Pratto has expert power. As another example, a surgeon may have power in a hospital because people depend on her or his knowledge and skill.

Expert power is a function of the amount of knowledge one possesses relative to the rest of the members of the group. This means that in certain situations, followers may have more expert power than leaders. When a new manager is appointed, the followers (who have worked at the job for 10 years) have more expert power than the leader.

Referent power is a function of the leader and follower. It is the potential influence one had due to the strength of the relationship between the leader and followers. When the leader is seen as a role model, he/she has referent power. Referent power takes time to develop. It can also have a downside. A desire to keep referent power may limit a leader’s actions in some situations. Managers that want to be liked by employees may have a hard time firing an incompetent employee, even when the person is costing the organization more money than they are bringing in.

Legitimate power is a function of the situation. It depends on a person’s role in the organization and can be thought of as one’s formal authority. The boss has the legitimate power to assign projects and the teacher has the legitimate power to assign papers and homework. Legitimate power means that a leader has authority because of the role he or she has been assigned in the organization.

Keep in mind that legitimate power and leadership are not the same thing. Holding a position and being a leader are not synonymous. While the head of an organization may be a true leader, s/he may also not be a true leader. People need more than legitimate power to be successful leaders.

Reward power is a function of the relationship among leaders, followers, and the situation. It involves the potential to influence others due to one’s control over desired resources. Someone with reward power can give raises, bonuses, promotions, can distribute parking spaces, or can grant tenure. Baseball players can be elected to the all-star team. Since the fans can elect the players, they have reward power.

The rewards that are distributed depend on the situation. For example, fans can elect baseball players to the all-star team, but cannot elect to give the players new cars (not that they need them!) A manager at Wendy’s can choose the employee of the month, but cannot elect an employee to the all-star team.

In some situations a leader’s use of reward power can be a problem. A superior may think that a reward is valued when it is not. For examples, a manager at Target may think that employees really want to be the employee of the month. However, employees may think that this is a stupid reward, and don’t want their picture on the wall for everyone to see and make fun of. Another problem with reward power, is that it may produce compliance, but not commitment. Subordinates may get the job done to get the reward, but not do anything extra to make the company a better place.

Leaders can influence others based on reward power if they:

- Determine what rewards are available.

- Determine what rewards are valued by followers, and

- Establish clear policies for the fair administration of rewards for good performance.

Coercive power is a function of the leader and situation. It is the opposite of reward power. It is the ability to control others through the fear of punishment or the loss of valued outcomes. One example of coercive power that most of us are familiar with is a policeman giving tickets for speeding.

Coercive power can be used appropriately or inappropriately. An example of coercive power being used inappropriately was the cult led by Jim Jones. Under Jones’s direction, 912 people drank from large vats of a flavored drink containing cyanide. Jones had a history of leading by fear and thus held coercive power over his followers.

Coercive power can also be expressed implicitly. For example, employees may feel pressure to donate money to their boss’s favorite charity.

You may now want to know which type of power is best to use. Unfortunately, this question cannot be answered. The situation influences the type of power that a leader should use. Generally, though, leaders who rely mostly on referent and expert power have subordinates who are more motivated and satisfied, are absent less, and perform better (Yukl, 2009).

We also know a few things about effective leaders. First, effective leaders usually take advantage of all their sources of power. Second, leaders in well-functioning organizations have strong influence over their subordinates, but are also open to being influenced by them. Third, leaders vary in the extent to which they share power with subordinates. Finally, effective leaders generally work to increase their various power bases.

Influence Tactics

As we talked about earlier, power is the potential to influence others and influence tactics are the actual behaviors used by an individual to change the attitudes, opinions, or behaviors of a target person. There are a number of different influence tactics.

Types of Influence Tactics

We will discuss nine influence tactics. These are assessed by the Influence Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ; Yukl et al., 1992), which was developed to study influence tactics.

- Rational Persuasion: agents use logical arguments or factual evidence to influence others. An example of this would be when a politician explains that taxes need to be raised in order for school children to have new books and supplies.

- Inspirational Appeals: agents make a request or proposal designed to arouse enthusiasm or emotions in targets. An example is when a church minister pleas with members to donate money for a new church.

- Consultation: agents ask targets to participate in planning an activity. An example is when a town leader asks for the help of residents to help plan a new playground for the children.

- Ingratiation: agents attempt to get the target in a good mood before making a request. An example is a salesperson flatters you in order to convince you to buy a product.

- Personal Appeals: agents ask another to do a favor out of friendship. If you ask your friend to help you with a project because you’ve been friends for a long time, you are making a personal appeal.

- Exchange: influencing a target through the exchange of favors. If you ask a friend to watch your child because you watched his child last week, you are using an exchange tactic.

- Coalition Tactics: agents seek the aid or support of others to influence the target. An example is when several students band together in order to ask a teacher for a deadline to be moved up.

- Pressure Tactics: threats or persistent reminders used to influence targets. If a boss threatened the loss of salary or reward, he would be using pressure tactics.

- Legitimizing Tactics: agents make requests based on their position or authority. An example is when a principal asks a teacher to be on a committee and the teacher agrees because of the principal’s role, even though she doesn’t want to be on the committee.

Mini Activity

Can you think of a time when you used any of these influence tactics?

Influence Tactics

As we talked about earlier, power is the potential to influence others and influence tactics are the actual behaviors used by an individual to change the attitudes, opinions, or behaviors of a target person. There are a number of different influence tactics.

Types of Influence Tactics

We will discuss nine influence tactics. These are assessed by the Influence Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ; Yukl et al., 1992), which was developed to study influence tactics.

- Rational Persuasion: agents use logical arguments or factual evidence to influence others. An example of this would be when a politician explains that taxes need to be raised in order for school children to have new books and supplies.

- Inspirational Appeals: agents make a request or proposal designed to arouse enthusiasm or emotions in targets. An example is when a church minister pleas with members to donate money for a new church.

- Consultation: agents ask targets to participate in planning an activity. An example is when a town leader asks for the help of residents to help plan a new playground for the children.

- Ingratiation: agents attempt to get the target in a good mood before making a request. An example is a salesperson flatters you in order to convince you to buy a product.

- Personal Appeals: agents ask another to do a favor out of friendship. If you ask your friend to help you with a project because you’ve been friends for a long time, you are making a personal appeal.

- Exchange: influencing a target through the exchange of favors. If you ask a friend to watch your child because you watched his child last week, you are using an exchange tactic.

- Coalition Tactics: agents seek the aid or support of others to influence the target. An example is when several students band together in order to ask a teacher for a deadline to be moved up.

- Pressure Tactics: threats or persistent reminders used to influence targets. If a boss threatened the loss of salary or reward, he would be using pressure tactics.

- Legitimizing Tactics: agents make requests based on their position or authority. An example is when a principal asks a teacher to be on a committee and the teacher agrees because of the principal’s role, even though she doesn’t want to be on the committee.

Mini Activity

Can you think of a time when you used any of these influence tactics?

Influence Tactics and Power

One’s influence tactic of choice depends on many factors such as intended outcomes and one’s power relative to the target person.

There is a strong relationship between the relative power of agents and targets and the types of influence targets used. Leaders with high amounts of referent power have built up close relationships with followers and may be able to use a wide variety of influence tactics. Leaders with high referent power generally do not use legitimizing or pressure tactics. Leaders who have only coercive or legitimate power may be able to use only coalition, legitimizing, or pressure tactics to influence followers.

People usually use legitimizing or pressure tactics when an influencer has the upper hand, when resistance is anticipated, or when the other person’s behavior violates important norms. People use ingratiation when they are at a disadvantage, when they expect resistance, or when they will personally benefit if the attempt is successful. People typically use the exchange and rational appeal when parties are relatively equal in power, when resistance is not anticipated, and when the benefits are organizational as well as personal.

Leaders should pay attention to how they are influencing others and to why they believe such methods are called for. Influence efforts intended to build others up more frequently lead to positive results than those efforts intended to put others down. One’s influence tactic of choice depends on many factors such as intended outcomes and one’s power relative to the target person.

Social Influence

In addition to the long line of research and theory on influence tactics in industrial and organizational psychology, social psychology also has created a substantial amount of knowledge in this area as well. In fact, social influence is considered a cornerstone of the field. One of the leading authors in this area is Robert Cialdini (2006; 2008), who has written a series of theory and science to practice books on the topic. But in general the idea of social influence is activating automatic processing (unconscious thoughts and behaviors that once triggered produce very predictable responses) in others for them to comply with your requests. In particular, there are certain behaviors that one can use to follow through with our requests.

We will highlight Cialdini’s 6 principles of social influence, but there are others that you may want to investigate.

- Reciprocity. One way to influence someone is to give them something. Humans are social creatures, and as such are programmed to return favors. That is why charities very often include “free gifts” when soliciting donations; it increases the amount of donations they receive as people feel obligated to return the favor.

- Commitment and Consistency. Very simply, if as a leader you can get a person to verbally or in writing commit to an idea, they are much more likely to follow through on it. This is particularly true if the commitment is restated consistently. This is actually the idea behind pledges of allegiance. In other domains of psychology you may have heard this referred to as “the best predictor of behavior is intention.”

- Social Proof. People will follow along with others. Again, as social creatures, people like to fit it in. So if other people are doing it, it must be a good thing. If you are at all familiar with Asch’s classic conformity studies using lines, this is the principle at work. Social proof is particularly effective in situations that are ambiguous or where there are no other clues as to how to behave, as people then start actively looking to others for what to do.

- Authority. As mentioned above, there is a certain power that comes from people being in charge. While people may complain about it, the majority will follow through on requests from authority figures. This was demonstrated in the classic research of Milgram as well as many study replications across the globe.

- Liking. We tend to listen to people we like. Who do you go to for advice? Do you often heed that advice? This is the idea behind why we are more likely to buy over-priced items from kids in our neighborhood when they are raising money for their school. Liking is also the principle behind why viral-marketing works (in addition to social proof).

- Scarcity. Would you like a Ferrari? Most people say yes to that question, but the reality of a Ferrari is that they are highly cramped to sit in with almost no cargo space (even going for an overnight trip is hard to pack for), incredibly high maintenance, and highly impractical (they are so low to the ground they very easily scrape the ground when there are changes in the angle of the road). But because only a limited number are made each year (orders often have to be placed years in advance) they become highly desirable because they are difficult to obtain. The same idea can apply in the work world. A rare promotion opportunity can entice quite a few people to work harder.

Overview of Theories Covered in the Course

Although the four components discussed on the previous pages are central to understanding leadership, there are many different perspectives from the past study of leadership. Not all approaches or theories we will cover include all components of our leadership definition from the previous page as many of these theories pre-date Northhouse (2013) by quite some time. And, no one theory alone (including the newer theories) is the best. Instead, much like the parable of the elephant, we believe we can learn from all of these perspectives. If you are not familiar with the parable of the elephant, watch the following video to hear the parable as told in the poetry of John G. Saxe (note: the story is thought to predate this author; the origin of the story is disputed).

Below you will find a very brief description of the different perspectives that we will study this semester. This is an overview to help you understand where we are going in this class.

- Leadership has been seen from a personality (or trait) perspective, which suggests that leadership is a combination of certain characteristics that individuals have that allow them to convince others to accomplish tasks. This is probably the most common conceptualization of leadership and may be how you have always thought of leadership. We will discuss the trait approach to leadership in the next lesson.

- The style and skills approaches emphasize the behavior of the leader. These approaches focus only on what leaders do and how they act.

- According to the situational approach, we need to focus on leadership in situations. Different situations demand different kinds of leadership. In order to be effective, leaders need to adapt their styles to the demands of different situations.

- The psychodynamic approach posits that leaders are more effective when they have insight into their own psychological makeup. Similarly, leaders are more effective when they understand the psychological makeup of their subordinates.

- Leadership has also been viewed as the power relationship that exists between leaders and followers. Leaders have power and use it to cause change in others.

- Contingency theory tries to match leaders to certain situations. In this approach to leadership it is believed that a leader’s effectiveness depends on how well the leader’s style fits the context. Contingency theory is concerned with styles and situations. It is different from the situational approach in that contingency theory believes that leader effectiveness is based on changing the situation versus the leader.

- Path-goal theory is about how leaders motivate subordinates to accomplish designated goals. The goal of this leadership theory is to enhance employee performance and employee satisfaction by focusing on employee motivation.

- Leader-member exchange theory (LMX) conceptualizes leadership as a process that is centered on the interactions between leaders and followers. LMX theory makes the dyadic relationship between leaders and followers the focal point of the leadership process.

- Transformational leadership, states that leadership is a process that changes and transforms individuals. It is concerned with emotions, values, ethics, standards, and long-term goals. Transformational leadership moves followers to accomplish more than what is usually expected of them. Authentic leadership grows out of transformational leadership but is about being leading by being true to oneself and convictions.

- Servant leadership is about meeting the needs of followers. It is similar to the situational approach and path-goal theory, but with a bigger emphasis on followers.

We will study all of these various approaches to leadership. We will spend the last few weeks discussing other issues (a bit more practical in nature) in leadership that are important in organizations today. We will talk about leadership in teams. We will also discuss leadership and diversity, since diversity is such an important topic in today’s workplace. Organizations are extremely interested in how to develop good leaders. Finally, in light of recent political, corporate, and other organizational scandals, we will discuss toxic leadership and ethics.

Assessing Leadership

There are a number of difficulties in assessing leadership. Personal opinions about leadership effectiveness can vary across individuals (i.e. one person’s maxim can vary differently from another person’s). Your idea of an effective leader (or manager) may be different than mine. You may think that a good teacher is easy and gives lots of A’s. I may think that a good teacher really challenges students and doesn’t give any A’s.

It is important for organizations to choose good leaders because the wrong decision could cost stockholders billions of dollars and lead the organization to fail. For this reason, researchers have studied ways to identify leadership talent, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Qualitative Approach

The most common qualitative approach is the case study. Case studies are in-depth analyzes of leaders’ activities. Case studies can provide leadership practitioners with ideas on what to do in different leadership situations. They can show us what traits are associated with leader effectiveness. The problem with case studies is that there is no objective way to determine whether the actions taken actually caused the results, as we discussed above with regards to maxims.

Quantitative Approach

Quantitative approaches focus on numbers rather than description to measure performance of leaders. The most widely used measure of performance is to use performance appraisal ratings of the individual. In performance appraisal ratings, the leader’s superior would rate performance on several dimensions and then provide a recommendation (or not) for a promotion. In our department head example, we may ask the dean to rate our department head.

A better way to judge leadership success may be through subordinates’ ratings of leadership effectiveness. To do this, we would simply ask the subordinates to rate their level of satisfaction with their leaders. Thus we may ask individual professors to rate their satisfaction with the department head.

Finally, we could use unit performance indices to examine what impact leaders have on the bottom line of the organization. We could judge leadership success by examining profit margins, or win-loss records. We could judge the success of our department head by judging how much money the psychology department raised per year or how many students the department graduated.

Ideally we would combine several of these measures of performance to create a more holistic picture of the leader's potential, in this case our department head.

To assess the relationship between factors like a leaders traits and their performance, we could use quantitative approaches to in correlational studies or experiments. You have probably studied these approaches in other classes, but we will briefly discuss them as an important review for some and as an introduction for the rest.

Correlational studies

Correlational studies help us know the statistical relationship between leaders’ traits, mental abilities, or behaviors and various measures of leadership effectiveness such as subordinates’ satisfaction. For example, a correlational study could help us know if there is a relationship between how satisfied psychology professors are with their department head and the number of psychology students that graduate from that department.

A correlation coefficient can be calculated. Correlation coefficients range from -1.00 to +1.00. Coefficients close to 1.00 would indicate a strong positive relationship and those close to -1.00 would indicate a strong, negative relationship.

Let’s say that we found a correlation of .81 between professor satisfaction with the department head and the number of students who graduated from the department. This means that as professors are more satisfied with their department head, more students graduate from the department. This relationship is positive, and fairly strong.

The main problem with correlational studies is that it is hard to make causal inferences based on correlational data. Thus, we cannot assume that the teacher satisfaction with the department head caused more students to graduate. We only know that there is a relationship between teacher satisfaction and the graduation rate of students. It is possible that higher graduation rates increase professor satisfaction. Remember, correlation does not mean causation. A correlation is simply a description of a relationship between two variables. For all we know it could be a third variable causing both. In this case, maybe easily available research funds for this department make professors satisfied and provide students with ample learning opportunities.

Experiments

Experiments allow researchers to make causal inferences about leadership. Experiments consist of both independent and dependent variables. The independent variable is what the research manipulates. The independent variable could be some type of leadership behavior. The dependent variable is what we are interested in measuring and is usually some measure of leadership effectiveness.

We may want to know if there is a relationship between the amount of time a leader spends with subordinates (independent variable) and subordinate performance (dependent variable). We would design an experiment with two groups. In the first group, leaders spend only 5 minutes a day with each subordinate. In the second group, leaders spend 30 minutes a day with each subordinate. Subordinate performance could be measured with performance on a test. We would look to see if those subordinates who spent 30 minutes daily with their leaders scored higher on the test than those who spent only 5 minutes daily with the leader.

Lesson 1 Wrap-Up

This lesson has helped us understand the different types of explanations for leadership; theories and maxims. But it has also helped us start to get an idea of what leadership is and how we will study leadership in this class. We defined leadership and discussed that leadership is a process. Leadership is an interaction between followers and leaders in different situations.

Next we talked about how we can study leadership in many different ways. In this class, we will look at a number of different approaches to leadership including the trait approach, style approach, situational approach, psychodynamic approach, power approach, contingency theory, path-goal theory, leader member exchange theory, and transformational leadership theory.

In this lesson, we also discussed the interaction of power and leadership. We differentiated between power and influence and discussed sources of power: expert power, referent power, legitimate power, reward power, and coercive power. Using each of these types of power has pros and cons. Leaders and follower utilize different types of power in different situations.

Leaders and followers use a number of influence tactics in order to influence behavior. These tactics include: rational persuasion, inspirational appeals, consultation, ingratiation, personal appeals, exchange, coalition tactics, pressure tactics, and legitimizing tactics.

Finally, knowledge of some basic human tendencies can allow a person to use social influence. The 6 principles are: liking, social proof, commitment and consistency, authority, scarcity, and reciprocity. Uses these principles can trigger automatic behaviors in others to comply with requests.

Finally, we discussed leadership assessment. We learned that the traditional ways of choosing leaders such as using application blanks and unstructured interviews are not valid. Rather, we should create competency models and use a multiple-hurdles approach to choose leaders. We can tell if there is a relationship between leader attributes and leadership effectiveness through both qualitative methods (including case studies) and quantitative methods (correlations and experiments).

Lesson 1 References

Bass, B. M., (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership. 3rd ed. New York: Free Press.

Bickman, L (1974). The social power of a uniform. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47-61.

Cialdini, R.B. (2006). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York: Harper Collins.

Cialdini, R.B. (2008). Influence: Science and Practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. John Wiley & Sons.

French, J. & Raven, B. H. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies of Social Power. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

House, R. J. (1984). Power in Organizations: A Social Psychological Perspective. Unpublished manuscript, University of Toronto.

Hughes, R. L., Ginnett, R. C., & Curphy, G. J. (2012). Leadership: Enhancing the lessons of experience. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies.

Northouse, P.G. (2013). Leadership: Theory and Practice. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

"The Blind Men and the Elephant" in The Poems of John Godfrey Saxe (1872)

Yukl, G. A. (2009). Leadership in Organizations (2nd Ed). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Yukl, G. A., Lepsinger, R., & Lucia, T. (1992). Preliminary report on the development and validation of the influence behavior questionnaire. In K. E. Clark, M. B. Clark, & D. P. Campbell (Eds.), Impact of Leadership. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.