SPLED461:

Lesson 1: Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Introduction and Objectives

To complete this lesson, please do the following things:

- Read the textbook (Chapter 1).

- Read all content provided in this lesson.

- Complete all associated self-check activities, discussions, and assignments.

Lesson 1 Objectives

- At the end of this lesson, you should be able to do the following things specified in the textbook:

- Describe the characteristics of autism spectrum disorders.

- Explain how autism spectrum disorders are identified and diagnosed.

- Identify the changes in the definition of autism spectrum disorders.

- Discuss causal theories associated with autism.

- Describe instructional planning for students with autism.

Autism Spectrum Disorders

If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.

Individuals with autism are a very heterogeneous group. You may personally know someone with autism—you may work, go to school, have a friend, or have an acquaintance with autism. As you no doubt know, each person's characteristics make them who they are. Although we’ll be discussing common characteristics, teaching strategies, and other educational issues related to autism, generalizations about characteristics can be inaccurate or can mask uniqueness. Remember that no size fits all; throughout your life, you’ll interact with unique and special individuals with autism.

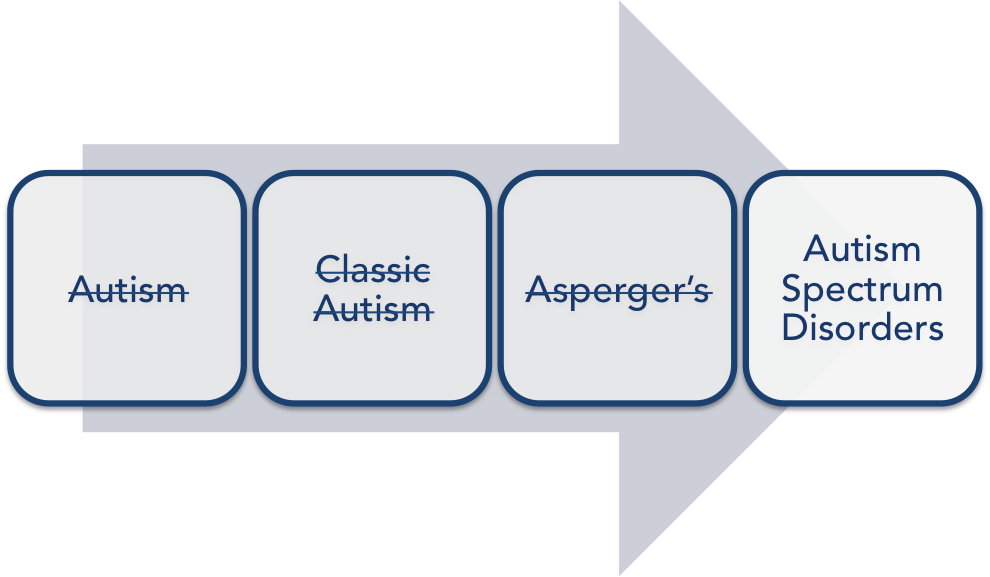

Before we begin, let’s talk about language and terminology. You may hear a lot of terms associated with autism. At present, the term autism spectrum disorders (or ASD) is used to replace such diagnoses as autism, classic autism, or Asperger’s. The new term ASD emphasizes that autism is a “spectrum” disorder, with a lot of variability in strengths and needs among those with the disorder.

This lesson's readings will provide you with an overview of ASD. First you will read about recent changes made to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or the DSM. The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and is the primary manual used by clinicians to provide a formal diagnosis. The DSM outlines specific criteria needed to receive a diagnosis, provides labels or names for the diagnosis, and lists the numerical codes that are sometimes used by insurance companies to bill for services. Essentially, the DSM provides the standard guidelines for clinicians to use for a formal diagnosis. After you read about the DSM, the lesson will cover potential causes of ASD, characteristics of the population with ASD, and instruments used to diagnose ASD. Finally, you'll look at the general parts of an individualized education plan (IEP) and how one might write a goal for a person with ASD. Let’s start with the DSM.

The DSM-V

The latest edition, the DSM-V, was published in 2013; it covers many different disability and diagnostic categories (such as intellectual disabilities, attention-deficit disorder, and other medical conditions). Most of the diagnostic categories have remained unchanged. However, in the recent edition of the DSM (V), there have been major changes to how ASD is diagnosed. Why was the DSM changed? Well, clinicians wanted to make the ASD diagnosis more specific to provide greater sensitivity, so that true cases would be identified. They also wanted the criteria to be more reliable (so that clinicians would agree on who had ASD), to be valid (accurate), and to really reflect that ASD is a set of behaviors. As seen in the DSM-V, ASD is characterized not by separate symptoms, but by a particular set of behaviors that manifest themselves together.

The changes in the DSM are relatively new; in fact, they're the first substantial changes to the manual in 13 years. As you can imagine, the systematic use of the DSM-V will take time. You may continue to hear terms that are no longer in the DSM-V (like Asperger’s). However, for accuracy, we will be using only the new terms and criteria. Below, you will find two charts; one outlines the changes made to the ASD diagnosis from the DSM-IV to the DSM-V. If you’ve had contact with individuals having ASD, you’ve likely seen a great deal of variability in how well each person is able to function. As outlined in the diagnostic criteria, there are two central deficit areas: social communication deficits, and restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. Recently added to the latest version of the DSM is a rating (from one to three) of the severity of the deficit areas. For example, an individual may be diagnosed as Level 3 in the area of social communication, but have less-severe symptoms of repetitive behaviors, which need only a moderate level of support (Level 2). Currently, there are no specific guidelines on how to assign a severity level.

|

|

DSM-IV |

DSM-V |

|---|---|---|

|

Definition |

|

|

|

ASD subtypes |

|

|

|

Clinical features |

ASD was characterized by three core symptoms:

|

In the DSM-5, there are now just two symptom categories:

|

|

Onset |

Onset before 36 months of age |

Now there is more of an open definition: “Symptoms must be present in early childhood, but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities.” |

Adapted from Diagnostic Criteria for Autism Under the DSM-5, by G. Vivanti, O. Tennison, and D. Pagetti Vivanti, 2016. In Autism Europe: About Autism.

The second chart shows the recently added severity scale, which describes the impact of ASD on everyday function.

|

Severity level |

Social communication |

Restricted, repetitive behaviors |

|---|---|---|

|

Level 3 "Requiring very substantial support” |

Severe deficits in verbal and nonverbal social-communication skills cause severe impairments in functioning, very limited initiation of social interactions, and minimal response to social overtures from others. For example, a person with few words of intelligible speech who rarely initiates interaction and, when he or she does, makes unusual approaches to meet needs only and responds to only very direct social approaches. |

Inflexibility of behavior, extreme difficulty coping with change, or other restricted/repetitive behaviors markedly interfere with functioning in all spheres. Great distress/difficulty changing focus or action. |

|

Level 2 "Requiring substantial support” |

Marked deficits in verbal and nonverbal social-communication skills, social impairments apparent even with supports in place, limited initiation of social interactions, and reduced or abnormal responses to social overtures from others. For example, a person who speaks simple sentences, whose interaction is limited to narrow special interests, and who has markedly odd nonverbal communication. |

Inflexibility of behavior, difficulty coping with change, or other restricted/repetitive behaviors appear frequently enough to be obvious to the casual observer and interfere with functioning in a variety of contexts. Distress and/or difficulty changing focus or action. |

|

Level 1 "Requiring support” |

Without supports in place, deficits in social communication cause noticeable impairments. Difficulty initiating social interactions and clear examples of atypical or unsuccessful response to social overtures of others. May appear to have decreased interest in social interactions. For example, a person who is able to speak in full sentences and engages in communication but whose to-and-fro conversation with others fails, and whose attempts to make friends are odd and typically unsuccessful. |

Inflexibility of behavior causes significant interference with functioning in one or more contexts. Difficulty switching between activities. Problems of organization and planning hamper independence. |

Adapted from DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria, by Autism Speaks, Inc., 2016. In Autism Speaks: What Is Autism?

Diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorders

Making an accurate diagnosis of ASD can be challenging. Often, many individuals are involved in the diagnostic process, including physicians, psychologists, teachers, parents, and sometimes the individual with ASD him- or herself. A variety of instruments can be used to aid in diagnosis. Typically, instruments called screeners are used initially to see if an issue does indeed exist. Screeners are often given to parents and teachers to begin the diagnostic process. If the child does show characteristics of ASD, a formal diagnosis can begin. The physician or parent can contact a psychologist (privately or in the school in which the child is enrolled) and make a formal request for an evaluation. Whoever conducts the evaluation will likely use the DSM-V to make a diagnosis. Once a formal diagnosis of ASD is given, the child can begin to receive services.

Causes of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Historical Context

In the 1960s, a psychologist named Bruno Bettelheim did quite a bit of damage by relating the cause of ASD to “refrigerator mothers.” The mothers of children with ASD were characterized as cold and distant (but only the mothers!). The mothers were often stereotyped as being highly educated and more career oriented than other mothers. This theory did a lot of damage by blaming parents; sometimes, you will still hear that poor parenting or a cold mother is the cause of a child having ASD, even though the theory has been soundly disproven.

Genetics

As your text states, research clearly has indicated that genetics strongly influence the risk of developing ASD. Unfortunately, we still do not know the extent of the relationship or the exact gene(s) that may be causing ASD. However, we do know that siblings have a greater risk of developing ASD. This is particularly true if we look at twins; if one twin has autism, there is a 90% chance that the other will as well. This provides a very strong indication of a genetic link, since identical twins are so similar. We also find that, if we look back in time, very often, a child who's diagnosed with ASD will have a family member with some characteristics, even if he or she wasn't formally diagnosed. So, we're seeing a strong genetic link occurring, but at this juncture we can't pinpoint the exact gene(s).

Role of the Environment

Although genetics plays a part in the development of ASD, it is generally acknowledged that genetic makeup alone does not account for all incidences. Many believe that the environment may also play a role. Environmental factors can include such toxins as pesticides or household cleaning agents, though the role of toxins still is widely debated. In fact, there still is controversy about whether the mercury in vaccines (now absent) causes ASD. Despite resounding evidence to the contrary, the theory of this environmental toxin continues to this day. Because environmental factors can refer to anything other than changes in a gene’s DNA, environmental risk factors for ASD may also include things like parental age at conception, maternal nutrition, infection during pregnancy, and prematurity.

Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorders

“Universities are renowned for their tolerance of unusual characters, especially if they show originality and dedication to their research. I have often made the comment that not only are universities a 'cathedral' for worship of knowledge, they are also 'sheltered workshops' for the socially challenged.”

– Tony Attwood, The Complete Guide to Asperger's Syndrome

Language Deficits

Not all children with ASD will display language deficits. Ability to communicate will vary by age and by individual. Some children with ASD may not be able to speak, while others may have rich vocabularies and be able to talk about specific subjects in great detail. Some children with ASD may display echolalia, in which they repeat words or phrases rather than engage in typical conversation. Echolalia can be immediate or delayed. An example of immediate echolalia would be when I say, "Good morning," and you say, "Good morning." I say, "How are you?" and you say, "How are you?" With delayed echolalia, the child can verbatim state a phrase that occurred some time ago. Some children can watch a movie (seems like it’s often Disney!) and can give you the entire script a few hours or even days later.

Additionally, the individual with ASD may have limited or delayed speech, such as single-word utterances or approximations of words. For example, instead of saying “ball,” the child says “ba.” The limited or delayed speech might mean that the individual with ASD has adequate speech, but difficulty with forms of language. His or her prepositions might be off; pronouns might be different. You might also see individuals with ASD who have no functional speech. They might be using other forms of communication, such as augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). For example, they might be using sign, a communication board with pictures, or a voice-output electronic system for communication.

"I can’t wrap my head around this."

"A penny for your thoughts."

"The ball is in your court."

"Costs an arm and a leg!"

"burning the midnight oil"

Some individuals might have problems with what we call pragmatics, meaning that they might not understand the social norms related to language. One common issue is misunderstanding sarcasm (as in, "Oh sure, I’d love to do that…"). Individuals with ASD may also use language in unusual ways, such as inappropriately using formal words, describing things in odd ways, having difficulty in conversation, or lecturing in a formal tone during informal discussions.

One common language deficit is the inability to comprehend idioms. As you know, idioms are expressions or figures of speech that aren’t to be taken literally. If you’ve ever interacted with someone from a different country, you know that idioms often differ from country to country. Idioms can be very difficult for individuals with ASD to understand; they might think it’s literally raining cats and dogs!

Individuals with ASD can also have difficulty understanding nonverbal communication, facial expressions, gestures, and/or proximity. For example, individuals with ASD might not interpret someone stepping back as a sign they're standing too close. They might also present with a very flat affect. For example, they might not display facial expressions in response to someone who's telling a very animated story. We don’t always think of nonverbal communication, but it is very important in conveying a message. Lastly, individuals with ASD might have difficulty processing language in distracting environments, such as a noisy environment or an environment with a lot of stimuli (like a cafeteria or a loud mall).

Now that you have read about the language deficits related to ASD, watch the following videos to get an idea of what these language deficits might look like in action.

Delayed Echolalia

In the first video, you will see an example of delayed echolalia. This young man is using what we call scripted dialogue. He's very interested in Tigger from Winnie the Pooh and uses exact lines from the movie. You’ll see that he's trying to get his mom involved in the dialogue because he wants her to recite the phrases with him.

Augmentative/Alternative Communication (AAC)

In this clip, you will see a boy named Timmy using augmentative/alternative communication (AAC). He's touching a screen that has a symbol on it. Once the symbol is pressed, there is voice output. Timmy has some behavior problems, but his communication device serves to decrease the inappropriate behaviors by allowing him to communicate more effectively.

Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)

In this clip, you will see Andy, who is 10 years old and has cerebral palsy and ASD. He is nonverbal and uses AAC. He is learning how to use a picture exchange communication system (PECS) to communicate with people who do not know sign language. When using a PECS, he selects the picture icons, places them on the strip at the bottom of the binder, pulls off the message, and hands it to the person to indicate what he or she wants/needs.

Social Differences

Next, your text discusses social differences related to ASD. Individuals with ASD may have deficits in what has been called theory of mind. This is sometimes referred to as mind blindness. Mind blindness is the inability of the individual to take the perspective of someone else. Much like the Greek word auto, which means being involved in oneself, individuals with ASD might not understand what others are thinking or perceiving or that their perceptions might differ from others'. For example, if they're frustrated with something, they assume that everyone else is frustrated with it as well. If they are okay with things, they assume everyone else is as well.

Joint Attention

Along with deficits in theory of mind are deficits in joint attention. Joint attention is the ability to share an experience. For example, as you watch TV, you say to your friend across the room, “Oh my gosh, that's funny—look at that!” You look at the other person; they look and are laughing too. You have just jointly shared in an experience.

Below is a video segment related to joint attention. This is a wonderful experiment that highlights the concept of joint attention. The researcher has three groups of children: individuals who are neurotypical, individuals who have intellectual disabilities (ID), and individuals who have ASD. The researchers are testing the children's reactions to various situations, such as someone getting hurt or being scared. As you'll see, the individuals with ASD don't always pay attention to others, don't always look or share the experience, and don't always understand others' points of view. It's really intriguing in this clip to watch the child with the ID. At one point, he just gets up and fixes the problem for the group, saying, "All gone." I like the way he thinks!

There also may be deficits or differences in the play of children with ASD. For example, you might observe more instances of parallel play (side by side but not together). Typically, developing young children will engage in parallel play, but eventually they'll move to cooperative play, in which they engage with each other. You see less cooperative play in children with ASD. This, of course, goes hand in hand with the issues of joint attention just discussed. There is a lot less sharing of experiences with others.

Individuals with ASD can also display social differences that are quite subtle in nature. For example, a common issue is that of personal space, with people with ASD often standing too close to another person. A good example of this can be seen in the Seinfeld episode about the “close talker.” If you stand too close to someone's face when they're talking, it can be very disconcerting. They might step back as a natural reaction. The person with ASD, though, will sometimes step up a little bit more; he or she might not understand the parameters of personal space.

Also, individuals with ASD often lack eye contact; they might not look at you when you speak. This can also be very disconcerting. Of course, lack of eye contact varies with culture, but, in the United States, not looking someone in the eyes while he or she is speaking can make you appear untruthful or uninterested in what is being said. Additionally, some individuals with ASD may appear uninterested or self-centered, wanting to talk only about their topic of choice. Another social difference is the inability to start a conversation or maintain it. For example, if you say, “How are you?” most people will say, “Fine.” You might continue and say, “What did you do last night?” Typically, the person you ask will detail the night’s activities. If you're engaging with a person with ASD, though, the conversation may just stop. The person with ASD may be unable to maintain an ongoing conversation or to engage in the typical back-and-forth exchange we have when we talk with others.

Repetitive Behaviors and Restricted Interests

Another diagnostic criterion of ASD is repetitive behaviors and restricted interests. We’ve already discussed that "individuals with ASD" is a very heterogeneous group. This heterogeneity can be manifested in the type of repetitive behaviors and restricted interests that are evidenced. Repetitive behaviors are those that are repeated over time. Some individuals with ASD engage in the self-stimulatory (sometimes called stereotypical) and repetitive behaviors of rocking and hand-flapping. You might work with a child who has the self-stimulatory behavior of tugging on the bottom of his shirt and making a noise each time. Below is a video of a child engaging in such stereotypic behavior.

There can also be an insistence on sameness. Some individuals with ASD really dislike changes in routine. If a particular person is absent one day at school, the child may have a great deal of difficulty coping that day. If gym class is cancelled due to weather, the child might display behavioral problems due to difficulties with the change in routine.

Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB)

Individuals with ASD also may engage in self-injurious behavior (SIB) or aggression. Self-injurious behavior can range from mild to quite severe. Some individuals with ASD may bite their hands; some may hit their heads. Others may have extreme SIB, such as gouging their eyes and causing blindness or gouging their ears and causing hearing problems. Extreme instances of SIB can be very difficult to handle and require immediate attention if they are life-threatening. Individuals with ASD might also engage in physical aggression toward others (e.g., kicking, hitting, or scratching) or display verbal aggression (talking back or using profanity).

Below, you will see an example of a young man who displays self-injurious behavior. You'll notice that he's wearing a helmet. He may be wearing the helmet due to seizures or for protection from his head-hitting. He wears headphones to cut down on noise, and you'll see him chewing on some rubber tubing, probably to keep him from grinding his teeth. His self-injurious behaviors are head-hitting, biting, and slapping his legs. His family has put up several videos; you will probably be able to tell that they're very frustrated, feeling that they need a lot more support in the home. This is a more extreme instance of SIB that shows that life at home may be very difficult and that additional support for the family may be needed.

Savant Skills

A relatively small portion of individuals with ASD may display savant skills. You might also hear this referred to as "splinter skills" or "islands of genius," wherein the individual can be quite low-functioning in some areas of development, but can have great abilities in others. Savant skills typically occur in areas like music, art, or mathematics. You can see an example of savant skills in the movie Rain Man, where Raymond, who has ASD, has difficulty with functional skills but great mathematical and memorization abilities. Savant skills are often portrayed in popular media, so many think this is how individuals with ASD function; however, the condition is not very common. Savant skills occur only in about 1% of individuals with ASD.

Below is a fascinating clip of a man named Stephen Wiltshire, who has savant skills. He’s sometimes called “the living camera.” He didn't talk until the age of five, but at age 11 he began drawing very complex scenes from memory. In this clip, researchers took Stephen to Rome, gave him a 45-minute helicopter ride over the city, and then asked him to draw the city. The level of accuracy and detail is phenomenal. Again, remember that savant skills are not commonly evidenced in individuals with ASD—but they are fascinating!

Also, subsumed under the category of repetitive behaviors and restricted interests are individuals with ASD who have very set routines, compulsions, or rituals. For example, before they are able to leave the house, they might need to do certain things each time (check the stove, touch the light switch, turn the knob three times, etc.). These individuals are also going to have difficulty with change. They might have trouble problem-solving if the situation is unfamiliar. For example, if someone has the day off of work and an individual with ASD is now responsible for picking up the colleague’s part of the job for the day, it may be difficult for him or her to adjust.

Motor Deficits

Individuals with ASD often have what is called dyspraxia, or difficulty with motor planning. Some individuals may have balance issues or awkward movements, may walk on their toes, or may have delayed developmental milestones. Motor issues can be categorized based on the fine motor skills or the gross motor skills. Fine motor skills center on small muscle movements—things like buttoning a shirt or getting the cap off of a tube of toothpaste. Gross motor skills involve large muscle groups, typically dealing with ambulation (walking) and being able to move one’s arms in a wide circle.

Gross Motor Skills

Motor issues are addressed through occupational therapy (OT) or physical therapy (PT). Occupational therapists often work with children with ASD on handwriting issues, helping them hold the pencil or pen correctly and helping them learn the amount of pressure to use when putting the pen to paper. Physical therapists may help individuals with ASD walk properly. Below, you will see a video of a child engaging in toe-walking, a gross motor skill.

Learning Challenges Associated With ASD

Generalization and Maintenance

Individuals with ASD may require explicit, systematic instruction. The ultimate goal of instruction for individuals with ASD is generalization, or the transfer of skills. When designing instruction, you want to make sure that the skills you teach will be transferred or generalized to other environments and with other people. For example, you might hear teachers say, “You know, he'll only sit in his seat with me” or “He will only respond appropriately with me.” You might think that this is a sign of success, but it's really not. You want the student to be able to respond with you, with his or her parents, and/or with a community worker out in the world. If you work with a student on telling time, you'll want him or her to be able to tell time on different clocks/watches. I You'll also want him or her to tell time at home, at school, and in the community. Remember, the ultimate goal of instruction is making sure the students can function anywhere they go based on the skills that have been taught.

Additionally, once a child learns a skill, it is important for him or her to maintain the skill over time (maintenance). Individuals with ASD often display deficits in maintaining previously acquired skills, so the ability to perform a particular skill over time cannot be assumed. Individuals with ASD need explicit training for generalization and maintenance to occur.

Challenges Associated With Core Deficits of ASD

Executive Functioning

Executive functioning is the ability to organize and plan using working memory, inhibiting and controlling impulses, time-management priorities, and new strategies based on what happens in the current situation or what has happened in the past. Deficits in executive functioning can affect your ability to know that you'll have to put your math supplies in your backpack before you go to class, where you'll need them. You might also forget the steps of a sequence ("I’m supposed to do four steps in this task, but I can’t remember past Step 2"). This can be very difficult for students with ASD, making it hard for them to complete tasks that require sequential steps.

Stimulus Overselectivity

Students with ASD may display stimulus overselectivity, wherein they focus on a small detail but are unable to see the big picture. You may also hear this described as "tunnel vision." Because the person is focusing on one small aspect, he or she is unable to pay attention to other parts of an object or other things taking place in the environment. For example, when looking at a car, a child with ASD would not focus on the car as a whole—including the color, shape, and individual parts—but, rather, would overselect, focusing only on the wheels.

Hyper/Hyposensitivity

Individuals with ASD often appear to sense the world in different ways than others. They may misinterpret everyday sensory information, such as touch, sound, and movement. For example, some individuals with ASD may find certain sounds or colors disturbing, while other individuals may not even hear the sound or notice the color at all. Both of these examples can cause learning challenges for individuals with ASD in the area of attention. Two common terms you may hear are hypersensitive and hyposensitive.

Individuals who are hypersensitive (oversensitive) receive too much information from their senses, so their brains become overloaded. This means they may see, hear, feel, smell, or taste things in a more extreme manner than other people. Some individuals with ASD have intense sensitivity to sound and may find certain sounds painful. Sometimes individuals will cover their ears or wear noise-cancelling headphones to help them tolerate noises.

Individuals who are hyposensitive (undersensitive) receive too little information, so the brain struggles to make sense of what little information there is. This means they may see, hear, feel, smell, or taste the world in a more muted way than other people. For example, an individual with ASD’s sense of touch may be lower than normal, and he/she won’t be able to feel light touches or even pain and temperature extremes.

Here is an interesting video designed to illustrate how hypersensitivity might feel to someone with ASD as he or she enters a store. Many of the sounds you may not have even noticed before become magnified. Please take a look at the Sensory Overload Simulation video.

Development of the Individualized Education Program

If a child has been diagnosed as having ASD, he or she will likely receive specialized services or accommodations in school settings. The document that details a plan for the provision of special services is called the individualized education plan (IEP). An IEP is a legal document that lists what services the child will receive, who is responsible for carrying out the services, how often the services will be received, and how data will be collected. Teachers, parents, specialists, medical personnel, and the individual with ASD can all be part of the team that develops this important document. The IEP is used as a blueprint for the instruction that will occur. Critical to the IEP are the goals and objectives that are developed for the student. These goals and objectives outline the activities and skills the student will be working on. Below, you'll find a primer on the parts of the IEP. You'll also see samples of well-written goals and objectives.

Six Required Parts of the IEP

Description of the Child’s Present Level of Performance or Functioning

This section describes the child’s current level of learning or performance, including performance in academic areas, functional skills, and behavioral skills. Descriptions of the child’s current interests and preferred learning style will also be addressed in this part of the IEP.

Annual Goals and Objectives

This section describes the specific skills the student will learn within a designated amount of time. Goals are typically long-term expectations for what the student will achieve within the school year. Objectives are more short-term expectations. An objective breaks down a goal into manageable pieces, or a skill into components.

Related Services

This section lists additional services that supplement the educational services the child receives in the classroom—for example, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

Educational Placement

This section describes the educational setting in which the IEP will be implemented.

Time and Duration of Services

This section lists the starting and ending dates for goals, objectives, and related services. It also specifies how often and for how long the related services will take place (e.g., the child will receive physical therapy three times per week for 30 minutes each session).

Evaluation of the IEP

This section lists and describes how the student’s progress toward short-term objectives and annual goals will be measured.

Creating Goals and Objectives

When writing goals and objectives, you are specifying the details of what you're trying to accomplish. Goals and objectives must be measurable and observable; this is critical for data collection and the ability to report student progress.

Well-written objectives must contain four pieces of information:

- the learner: Who is performing the behavior? Be specific and list the student's name.

- the behavior: This is the specific, operationally defined (i.e., observable, measurable, and repeatable) behavior that the learner will be required to display.

- the condition: Under what settings will the learner be expected to perform the behavior? Be specific as to what cues, materials, settings, and other people will be present.

- the criteria: These define how it will be determined that the student has displayed the behavior. Criteria can include number of times the learner must perform the behavior, the level of independence that must exist during the performance, and the time period across which the performances must occur.

Self-Check

Please note the components of the goal below based on the information above.

- Example: Given a calculator and two amounts (condition), Clifford (learner) will add the two amounts (behavior) with 90% accuracy in five consecutive trials (criteria).

Now try a few on your own. Look at the examples below and identify the four components. Please select the arrows to reveal feedback.