SPLED808:

Lesson 1: Introduction to Behavioral Assessment: Purpose and Building Rapport

Lesson 1 Overview

To be successful in this lesson, do the following:

- Read Chapter 1.

- Read the following articles. If not linked on this page, the articles can be found by selecting Library Resources in the Course Navigation Menu:

- Traub, M. R., Joslyn, P. R., Kronfli, F. R., Peters, K. P., Vollmer, T. R. (2017). A model for behavioral consultation in rural school districts. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 36(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/

-

Lugo, A. M., King, M. L., Lamphere, J. C., & McArdle, P. E. (2017). Developing procedures to improve therapist–child rapport in early intervention. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(4), 395–401. https://doi.org/

- View/download the Lesson 1 PowerPoint file. It will be available to you on the next page. Information on these slides will help you follow along when you watch video lecture segments in this course.

- Read all content in this lesson.

- Watch all video lecture segments and other examples.

- Complete all associated activities.

- Complete and submit Assignment 1.

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the purposes of conducting behavioral assessments including functional behavioral assessment, preference assessments, and skills assessments.

- Identify key stakeholders who should be involved in the assessment process.

- Discuss methods to build rapport with clients and teams.

What Is Behavioral Assessment?

Behavioral assessment is the process of systematically observing and measuring behavior in order to predict the future occurrence of the behavior of interest. The purpose of behavioral assessment is to inform a support or intervention plan.

Different types of behavioral assessments exist. The most common are

- functional behavior assessment (which may sometimes include functional analysis),

- preference assessments, and

- skills assessments.

Purposes of Behavioral Assessments

Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA)

When you give an FBA, you gather data both directly and indirectly in order to operationally define a problem behavior, understand the events surrounding problem behavior (setting events, antecedents, consequences), hypothesize the function(s) of the behavior, and gather baseline data in order to guide an intervention plan. An FBA may or may not involve a functional analysis (FA).

Functional Analysis (FA)

In an FA, you experimentally manipulate the antecedent and/or the consequent variables to observe and measure their separate effects on the problem behavior and determine the function(s) of the problem behavior.

Preference Assessments

In a preference assessment, you gather data directly and/or indirectly on a client’s preferences, which could include tangible items, edibles, types of attention, time alone, breaks from tasks, and so on in order to choose consequences that will serve as likely reinforcers. These likely reinforcers are used to teach the client replacement and other desired skills that skill compete with the problem behavior.

Skills Assessments

When you conduct a skills assessment, you gather data, usually directly, on a client’s behavioral repertoire. Skills assessments can be conducted within various domains such as adaptive skills, language skills, social skills, leisure skills, academic skills, and so on. The purpose is to help a team systematically choose skills to compete with problem behavior and ultimately improve a client’s quality of life.

Why Is Assessment Important?

Without first assessing, we are left to a willy-nilly approach to intervention. Assessments enable us to provide targeted intervention, increasing the efficiency of a treatment or support plan.

What Is an FBA?

It is often the case that, as behavior analysts, we see clients or students because of problem behavior. That is why one of the most common assessments we conduct is the FBA. This analysis is "designed to obtain information about the purposes (functions) a behavior serves for a person," which we can then use "as the basis for intervention efforts designed to decrease the occurrence of those behaviors" or increase the occurrence of positive behaviors (Cooper, Heward, & Heron, 2007, pp. 628–629).

FBAs are conducted in various settings, including homes, clinics, and hospitals. Perhaps the most common settings where FBAs are conducted is schools.

Did you know that the IEP (individualized education plan) team for a student whose behavior impedes the learning of themselves or others is required by federal law to "consider the use of positive behavioral interventions and supports, and other strategies, to address that behavior" (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2019)? Each state has various other legal requirements. Behavior analysts are not always involved in this process. Often times, a teacher, a school psychologist, or interim support personnel will conduct the FBA.

For more information regarding legalities of FBAs in schools, see the article Functional Behavior Assessments and Behavior Intervention Plans: Legal Requirements and Professional Recommendations by Collins and Zirkel (2017).

When behavior analysts conduct an FBA in homes and clinics within a behavioral health system, they work within the guidelines of that system. Regardless of the setting, an FBA should follow certain steps.

Steps of an FBA

- Review records and conduct indirect interviews.

- Observe the client or student directly.

- Write a hypothesis statement of problem behavior (also referred to as summary statement).

- Complete an experimental functional analysis (FA). This step is optional and more common in clinics, hospitals, and self-contained classrooms.

The Outcomes of the Functional Assessment Process

According to the O'Neill (2015) textbook, the functional assessment process has six primary outcomes (reproduced and reformatted from p. 5):

- a clear description of the problem behaviors, including classes or sequences of behaviors that frequently occur together;

- identification of the immediate antecedents that predict when the problem behaviors will and will not occur;

- identification of the setting events, times, and situations that predict when the problem behaviors will and will not occur across the full range of typical daily routines;

- identification of the consequences that maintain the problem behaviors (i.e., what function [or functions] do the behaviors appear to serve for the person);

- development of one or more summary statements or hypotheses that describe specific behaviors, a specific type of situation in which they occur, and the outcomes or reinforcers maintaining them in that situation; and

- collection of direct observation data that support the summary statements that have been developed.

Importance of Preference and Skills Assessments

Preference assessments are often conducted during the FBA process. The purpose of a preference assessment is to identify tangibles, activities, or other events that are likely reinforcers. These preferences are then incorporated into a behavior support plan (also referred to as a behavior intervention plan). However, preference assessments are also used periodically during educational and behavioral programming, even if the function of a problem behavior has not changed.

It is important to note that preferences change. We must not assume that a child will continue to "work" for the same toy every day. Some clinicians conduct brief preference assessments several times per day, while others may be able to verbally ask their clients about their preferences every few weeks. This will depend on the context.

Skills Assessments

Like preference assessments, skills assessments are often conducted alongside an FBA, such as during an intake or evaluation, as well as periodically to choose goals for a student or client. There are many different domains to assess, and the ones you select will depend on your client’s needs, the context in which you work, and resources. Table 1.1 shows some examples of domains covered in skill assessment.

| Adaptive Behavior | Language | Social Skills | Math Skills | Reading Skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding | Echoing sounds | Making eye contact | Counting | Identifying letters |

| Dressing | Asking questions | Starting a conversation | Multiplication | Blending phonemes together |

| Toileting | - | Resolving conflict | - | - |

Skills may fall into multiple domains. For example, sending a work email could be classified as an adaptive skill, social skill, or even language skill.

Many assessments are comprehensive and guide clinicians to assess across domains, while others are highly targeted.

Preference and skills assessment are often used by behavior analysts outside of an FBA and for clients who do not engage in challenging behavior. For example, in early intensive behavior intervention (EIBI), comprehensive assessments that address multiple domains are utilized in order to choose developmentally appropriate goals for comprehensive skill acquisition and generalization.

Companion Assessment Procedures

Remember that in applied behavior analysis, we are interested in improving socially significant outcomes. For this reason, it is imperative that we consider the values, culture, and quality of life of our clients and students.

Person-Centered Planning

Person-centered planning helps a team see the bigger picture and vision for a student's or client’s future. The plan is developed by the individuals who are actively involved in a person’s life. This could include family members, teachers, counselors, doctors, behavior technicians, or others. A person-centered plan is a great way to systematically identify a client’s strengths and preferences.

Now watch Video 1.1 on person-centered planning and complete the self-check that follows.

Self-Check

For this self-check, please read the question, think of your answer, and then select Show Answer.

Activity Patterns and Social Life

A client’s quality of life is greatly impacted by their activities and relationships. Remember to consider whether their preferences are represented in their routines and whether they are being included in their community (e.g., school activities, neighborhood and community events).

Medical and Physical Issues

Biobehavioral variables are important to consider during the FBA process. Behavioral interventions are not as effective or sustainable if the problem behavior is related to a medical or physical condition. Common conditions include allergies, sinus or middle ear infections, premenstrual and menstrual cycle effect, urinary tract infections, and chronic health conditions. Medications and side effects should also be taken into account. As this is often outside of the area of expertise of a behavior analyst, it is important to collaborate with a client’s team.

Who Should Be Involved During an Assessment?

The number and role of the individuals involved during an assessment will depend on a number of variables including the purpose of the assessment, the setting in which the assessment is being conducted, and the complexity of the client’s needs.

Building Rapport With Clients During Assessment

It is important to build trust and rapport with clients and the team during the assessment process. Remember that the purpose of conducting an assessment is to use the data to inform an intervention plan. Therefore, it is critical that we get buy-in from the team in the beginning of the process. This will make it much more likely that the team will follow through with the intervention and support strategies developed from the results of the assessment.

What Is Working Alliance?

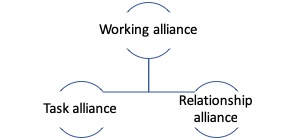

Working alliance can be a useful concept to help behavior analysts purposefully establish a productive behavioral assessment, ultimately leading to increased buy-in during treatment (Thompson, Bender, Lantry, & Flynn, 2007). Working alliance can be broken down into two areas: task alliance and relationship alliance.

Task alliance is an agreement between client and therapist regarding the purpose, goals, and tasks needed for social-significant change for a client.

Relationship alliance serves to build trust and rapport between the client and therapist.

During an initial meeting with the team, the purpose of the assessment should be explicitly stated. It is also important that the specific role of the behavior analyst be outlined during the onset of a case or consultation.

Here are some ways to establish rapport when consulting with adults during an assessment.

The Importance of Lay Language

Behavior analysis is a technical field, and it is important that you understand and are able to use technical language accurately. However, when conducting assessments, we are often working with multidisciplinary teams that include teachers, paraprofessionals, and parents who may be turned off by technical terms. Using everyday language, at least initially, may increase their comfort level with behavioral assessment and treatment.

Building Rapport With Young Children

Preference and skills assessments are often ideal opportunities to begin establishing rapport with clients. Would you perform better for someone with whom you felt comfortable? Children are no different. In early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) programs, for example, goals are developed across many different domains including language and listener skills, play skills, self-help skills, and pre-academic skills (counting, letter identification). It would be difficult for any child, especially one who needs systematic instruction, to sit down and demonstrate all of these skills “on demand.”

Pairingis often necessary and can help signal an “improvement of conditions” to the child. As indicated in the Lugo, King, Lamphere, & McArdle (2017) article, pairing procedures are also just good practice to use prior to intervention sessions. They describe the following strategies that practitioners can use to pair with young children that are derived from the play condition of functional analysis and behavioral parent training. Match each strategy to the definition.

References

Collins, L. W., & Zirkel, P. A. (2017). Functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans: Legal requirements and professional recommendations. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(3), 180–190.

Cooper J. O., Heron T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 45 U.S.C. §§ 1400–1482 (2019).

Lugo, A. M., King, M. L., Lamphere, J. C., & McArdle, P. E. (2017). Developing procedures to improve therapist–child rapport in early intervention. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(4), 395–401.

O'Neill, R. E., Albin, R. W., Storey, K., Horner, R. H., & Sprague, J. R. (2015). Functional assessment and program development for problem behavior: A practical handbook (3rd ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Thompson, S. J., Bender, K., Lantry, J., & Flynn, P. M. (2007). Treatment engagement: Building therapeutic alliance in home-based treatment with adolescents and their families. Contemporary Family Therapy, 29(1–2), 39–55.