SSED535:

Lesson 1: What is Historical Media Literacy?

Lesson 1 Introduction

What does it mean to teach or learn history through the use of popular media? After all, entertainment media make things up. Students are supposed to encounter true information and knowledge in school. What can people learn from media that make things up? Almost everyone will say that they know visual media depictions of the past aren’t totally “true” or accurate. Still, many people seem to find them true enough to make references to them when talking about history—or to get upset when they hear that Hollywood (or whatever industry) is making a media production that “inaccurately” portrays a social group or perspective they care about. Despite these widespread and legitimate concerns, many educators are drawn to include historically oriented media in their classrooms. Millions of students are drawn to engage with these media on their own outside of school. Almost everyone in modern society encounters some historically oriented media and has their thinking about or understanding of the past influenced to some degree.

Historically oriented media contain messages that their makers want to convey to audiences. Sometimes these messages can be chiefly commercial—with the purpose of appealing to audiences by making them feel good (inspirational stories), excited (adventure stories), or empowered (stories of national, cultural, or identity heritage). Sometimes messages can be serious, trying to persuade the viewer to reach a particular conclusion about how the past relates to the present. There may be a contemporary social or political cause that the makers (which can include writers, directors, and producers) want to advocate by depicting the past in a particular way. Commercial entertainment and serious purposes aren’t always in opposition. For example, historically oriented media can have the commercial purpose of appealing to diverse, multicultural audiences and the serious purpose of opposing racism, religious intolerance, or other discrimination—conveying a message that uses present-day values to make meaning of the past.

Media may want to “tell” audiences about things in the past and how to think or feel about them in the present, but it would be a mistake to conflate this purpose with teaching or learning. Teaching is more than just conveying messages to be consumed and internalized. Likewise, learning is more than just having your thinking or memory influenced by a conveyed message. Teaching (at least when done well) involves helping others to explore new ideas through applying knowledge and information. Learning (at least when meaningful) involves developing more robust understandings of complex phenomena. This is why it is problematic to think of media themselves as “teaching” when they are just consumed in the classroom. Rather, teaching is what educators do with media in the classroom, and robust learning comes from what students do in response.

Your initial readings this week will provide helpful orientation to these questions and issues that cut across the whole course. Each was selected for a different purpose. Toplin’s chapter provides some introductory theory on historically oriented film (and by extension other media forms). In particular, he offers an approachable take on what “truth” and “fact” and “accuracy” mean. In other writings, Toplin coined the term “faction” to describe how media such as film blend broad historical factuality with fictional details, invented characters, and imaginary circumstances in order to tell a narrative story. Toplin doesn’t use that term in this chapter, but keep his idea in mind as you read his cautious defense of filmmakers and history movies. The article by Butler, Zaromb, Lyle, & Roediger introduces you to pedagogical issues of teaching with media by looking at learning effects. In particular, pay attention to the potential for “misinformation” effects. Lastly, the article by Metzger & Suh introduces big implications for historically oriented media in the classroom. Even teachers with the best of intentions can end up using media for educationally weak or problematic outcomes due to a host of possible complications and pressures. You will notice that each reading chiefly aligns with one of the Discussion Table prompts—but you are encouraged to make connections across the readings and prompts at all of the Discussion Tables, this week and every lesson to come.

Objectives

In addition to becoming familiar with the structure of this course, the tools for interacting with class activities, and the members of this community, by the end of this lesson you should be able to

- articulate a definition of “historical literacy” that (1) includes mass media as both purveyors of content and as communication forms that convey messages in alternate ways, and (2) positions it as a skill for teachers and learning outcome for students;

- make arguments about the dynamics between factual accuracy (authenticity) and fictional creativity (imagination) in historically oriented media;

- take an informed position on what makes educational uses of historically oriented media appropriate or effective and when uses are inappropriate or ineffective;

- identify various historically oriented media examples; and

- analyze how various examples of historically oriented media use the past to convey messages to contemporary and present-day audiences.

Readings and Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 1 Course Schedule.

Lesson 1 Media Clip

Historically-oriented media have information and messages that their makers want to convey to audiences and provoke particular emotional, moral, and even political responses. To explore this, let’s watch a clip from director Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven (2005), which was produced and released in the years after the September 11 al-Qaeda terrorist attacks on the US and during the U.S.-led military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. The movie tells a story of the fall of the medieval crusader-kingdom of Jerusalem and the events leading up to the Third Crusade. At the end of the 11th century, Christian armies from Europe organized by the papacy seized the coast of the Middle East, including the holy city Jerusalem, from Muslim rulers. Decades later, Islamic armies commanded by the sultan Salah al-Din (Saladin) moved to retake the territory. The film revolves chiefly around the defense of Jerusalem after the army of the crusader-states was wiped out by Saladin at the battle of Hattin (1187). The film’s main hero Balian of Ibelin (Orlando Bloom) was an actual historical figure, though his representation in the film is a composite of several people, and he also is given a fictional background as an illegitimate blacksmith from France.

Keep all of this in mind as you watch this scene of Balian preparing Jerusalem to face Saladin’s siege. How does this scene convey messages to the viewer for our world in the present by using the historical past?

Click the white arrow to launch the video.

NOTE: Below is the title only of the complete video that will appear in the full course.

Kingdom of Heaven (2005)

Balian’s speech in Jerusalem

Tracks 35 and 36, running time 01:40:01 – 1:44:50

Instructor Analysis for Kingdom of Heaven

Telling the Truth about History

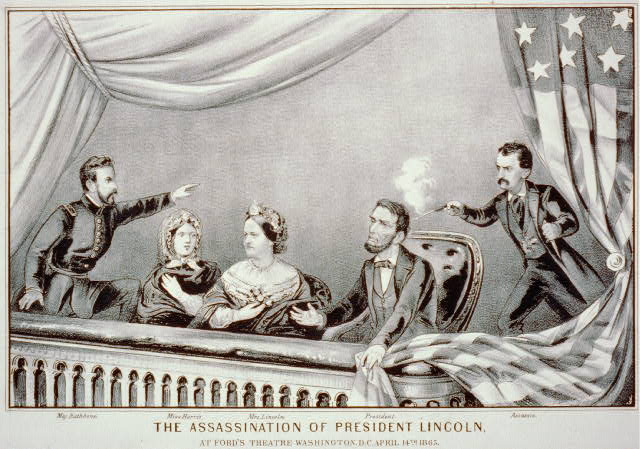

What does it mean to “tell the truth” about history? This question isn’t as simple as it might sound. “What really happened” is one simple response. And indeed this might work—if your question is straightforward enough and there is sufficient certain evidence to answer it. A true answer is easy for a descriptive question such as “When was Abraham Lincoln killed?” There is plenty of evidence (newspaper accounts, photographs) from the time clearly attesting that he died from a gunshot to the head in April 1865.

But what does it mean to tell the truth about history when the question isn’t descriptive and straightforward or when surviving evidence isn’t clear or comprehensive? The most interesting questions about the past involve “why?” or “how?” and usually don’t have straightforward descriptive answers. “Why did the US Civil War happen?” “How could the Union defeat the Confederacy despite losing so many early battles?” These are complex question without simple answers. Even different experts would give different expert answers to them—but they are the kinds of important questions that people really care about when they talk about history.

People talk about history because it is how the world came to be the way it is. More than just fascination with where things today came from, there is also a sense that the past is important because it matters to our identity, who we are, and why we believe what we believe today. It is why different social and ideological groups argue over “what happened” and the meaning of the past, over what should be included in school history textbooks or get taught in the classroom. Even many people who say they “don’t like” history still care about political and cultural issues that are very much affected by history. One of the most effective tactics in contemporary political debates is to compare a policy today to one that happened in the past (“History teaches us that…”). Given how powerful uses of history can be, a robust understanding what “truth” means in history becomes crucial.

Historical Stories

.jpg)

This sense of the past as important, valuable, or powerful isn’t new to modern society. People have always told stories about what they thought (or wished) had happened in the past. The earliest written works of human culture—the Homeric epics of ancient Greece, the Gilgamesh epic of ancient Mesopotamia—are set centuries earlier than when they were first told or written down. Historical stories have been a major part of literature around the world ever since. Back then, it was commonly expected that such stories would help the listener or reader understand some intellectual or moral truth—not that they would be literally true. Some scholars suggest this is why early Christians saw no problem with four differing gospel accounts of the history of Jesus’s life—each taught a different kind of truth. Of course, some ancient writers did purport that their accounts were actually true. The English word “history” comes from the ancient Greek term for making inquiries, as Herodotus claimed that his writings came from his travels to ask questions of people he believed knew what happened in the past. Yet this did not stand in the way of Herodotus filling his pages with fantastic tales (like men in central Asia whose heads were located in the middle of their chests).

Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War may be the first “modern-style" history, in that the author provides a researched, materialist account of what happened without supernatural elements. Yet this did not stop Thucydides from including lengthy speeches (such as Pericles’ funeral oration) that happened years earlier and which he could not have copied down in real time. Numerous medieval Islamic scholars studied the past to write books combining history, philosophy, and theology—such as Ibn Khaldun’s sociological history of the Arabs that also included speculation on dreams and visions. After the spread of printing and the growth of a publishing industry in Western societies, some of the most popular novels were historical stories—perhaps no one more successful than Sir Walter Scott. His fictitious novel of medieval English knighthood Ivanhoe (1819) influenced culture as far away as the American South (where many white landowners began to think of themselves as chivalrous and knightly). What distinguished the historical novels of the 19th century from earlier storytelling was that, unlike medieval legends such as King Arthur, they were set during known events and often relished historical details as backdrops.

History as a Scientific Discipline

It was not until the 19th century, after modern science spread across Western universities, that many people began to think history could be a scientific study of what actually happened in the past. The German scholar Leopold von Ranke, widely considered to be a founder of the modern historical discipline, said he was inspired to study history by discovering that Walter Scott’s novels had historical inaccuracies. History as a scientific discipline and historical fiction have been influencing each other for centuries now.

Historically Oriented Media

Mass media of the 20th and 21st centuries are new technologies for depicting the past, but they inherit the legacies of historical storytelling. What distinguishes modern historically oriented media from fantasy is that they are based, to some degree, on a known event or setting in the past, which gives them a greater sense of authenticity or realism. At the same time, like the historical novels that came before, historically oriented media also are based in creative imagination necessary to provide a complete story that includes visual details, full motivations, and satisfying conclusions which may not be available to an academic historical account. If there is not enough evidence to understand details of events or a person’s motivations in the past, academic history admits uncertainty and may only offer guesses. Only rarely do historically oriented media leave events or motivations uncertain (or offer multiple possibilities of what could have happened). When media face historical uncertainties, gaps in detail, or unsatisfying outcomes, they can turn to storytelling imagination to invent (or replace) details—and this is virtually demanded by modern audiences who expect a complete and satisfying narrative story. Imagination is absolutely essential so long as it doesn’t totally undermine the feeling of authenticity that gives historically oriented media more importance or legitimacy than pure fantasy.

Impact on Teachers and Students

How teachers and students can be prepared to deal what it means to “tell the truth” about history given the nature and influence of historically oriented media will be an implicit theme explored in the rest of the class. Our goal is to develop methods to take advantage of the sensory and emotive power of media in support of responsible and rigorous history education. The challenge isn’t simple or easy, but hopefully you will find it exciting, intriguing, and worth joining this class for the journey.