Main Content

Lesson 01: Overview of Strategy

- First Page

- Previous Page

- 4

- 5

- 6

- Next Page

- Last Page

Activities

Please complete the following assignments by the due date listed in the course syllabus. Refer to the Student Task Grid for a lesson-by-lesson assignment list.

Activity 1 - How to Perform an Analysis Individual Writing Activity

In this activity, you'll perform a strategic analysis. The video below explains how to perform a strategic analysis and will help you work through the process. Use the steps listed below the video to complete your assignment.

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK. So my name is Michelle Hough. And I'm a professor at Penn State. And I teach strategy. And strategy is by far the most interesting and vibrant and interactive of all the business disciplines, because strategy is like telling the future. If you get a good strategist, it seems like they know what's going to happen next. And they position their organization perfectly to take advantage of some future event that no one knew was going to happen.

Today, we're going to do a couple of segments on strategy. Some strategic tools. The first one is how to perform an analysis. And the second one is we're going to review a classic strategy case, Robin Hood.

Usually my students review 20, 30-page strategic cases about different companies. Robin Hood's a one-pager, so you're going to love it. And you're going to love to see how we can use that to create strategy and do strategic thinking.

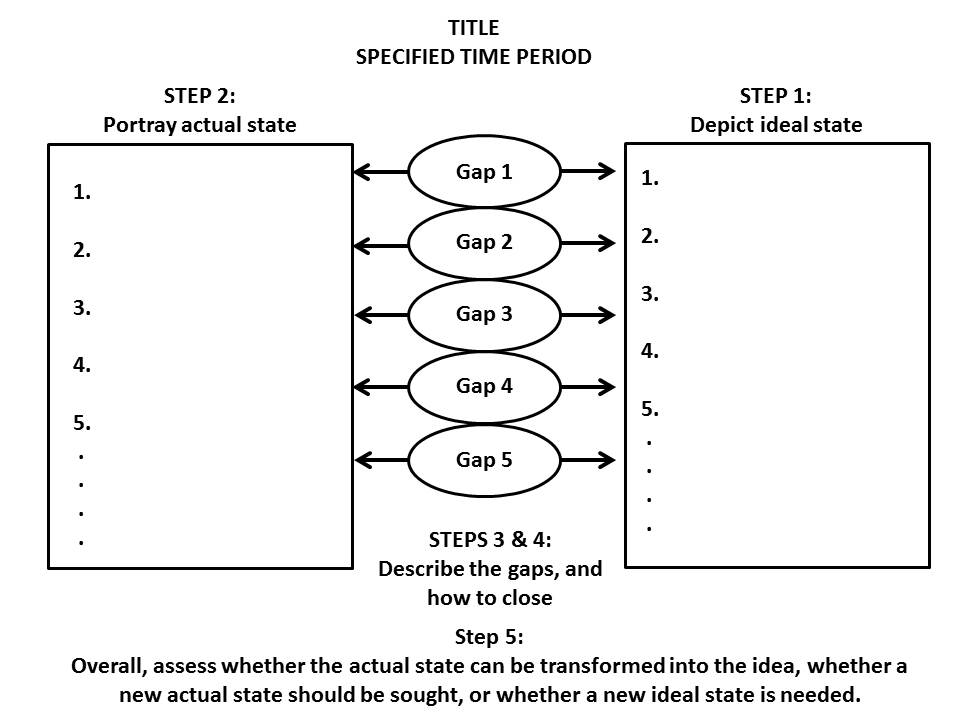

But first, if you'll take a look, you have a chart that looks like this. And this is a model of how to perform an analysis. Analysis is the key to strategy. If you can't do an analysis, you can't be a strategic thinker, very simply. And here's why. Analysis is also the key to success in an organization.

If you look at this pyramid, it looks sort of like an org chart that's all been compressed, right? Three types of managers in an organization, first-line managers, middle managers, top managers, including that rare person who gets paid a lot of money, the CEO. First-line managers are dealing with transactions in the corporation. They do transactional thinking.

So they worry about stuff, if, for example, your code goes. They worry about stuff like, how many gallons of milk do we need to sell this week? Oh, it looks like the milk's getting a little bit low, I better order some more whole milk, or I better order some more 2% milk, right?

The next level of managers take all the transactions that the first-liners perform, and they do analytical thinking. Analytical thinking takes the aggregates of transactions and looks for patterns. So the first-line manager might worry about, we need some more milk. It's Friday night. People are going to be buying milk for the weekend.

Middle managers look at something different. They say, hey, I have all these stores. And this particular store always runs out of skim milk on Wednesday. And I'm getting customer complaints. Why does that happen? Why do you think that would be happening? A particular store constantly runs out of skim milk.

STUDENT: Based on where it's located?

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK. So it's probably demographic related, right? You might assume that some stores have a population evenly dispersed of young families, single people, older people. And you may well have a location or two that have a different demographic.

And that becomes important because the middle manager needs to take this data, analyze it, and figure out what are the patterns. I don't want people running out of skim milk. And I don't want to have my whole milk going bad. So I need to figure out what's going on here, so that I can make sure that the stores use their inventory order and process their inventory effectively and efficiently.

When we talk today about how to perform an analysis, we're going to be looking at analytical thinking. And once you learn how to do an analysis, that means that you, at least, will make it to the middle level of an organization.

Some people can't do analyses. And unfortunately, if you're not an analytical thinker, you are doomed to this level of an organization. If you can't analyze, you can't get to middle manager. Likewise, middle management analytical thinking is the key to strategy and to strategic thinking.

Top managers get paid a lot of money. And we get really frustrated about that sometimes. Why? Two reasons.

First of all, they carry the risk in an organization. Although, we would probably say in today's business environment, top managers who carry the risk and then they let their companies fail, they don't get the consequences that you would assume. They rarely end up in jail. They rarely end up bankrupt. Usually, they end up with a pat on the back and golden parachute, right? So top managers carry the risk.

The other reason they are so highly compensated is because they're strategic thinkers. They look outside the box. They look at the bigger picture.

We'll use the phrase, which is particularly applicable to Robin Hood, they can't see the forest for the trees. Have you ever heard that phrase? That means somebody has a problem with strategic thinking.

So these are the three levels of organization. Almost anyone can do transactional thinking. Today, we'll focus on analytic thinking. And then, once we've got that down pat, we'll show the differences between analytic and strategic thinking and how to turn people into true strategists, so you can make the big bucks.

Unfortunately, analytical thinking, is not taught in schools. As a matter of fact, when I started teaching strategy, I had a hard time finding a model of how to portray analysis. This document that you see--and you all should have a picture of this, we'll be working off of this for a while-- is actually, if you look at it, I made it up several years ago, because I literally could not find a model that depicted analysis very well. I don't know that it's the best, but we'll work off of it. And it seems to have worked fairly well over the years.

The thing about analysis is that analysis isn't just a business skill, it's a life skill. You've probably all known people who are miserable. Did you ever meet somebody who's just miserable in their life, in their job, in their relationships?

I know a couple of these people. And I say, well, what's wrong? I don't know. I hate my job.

Well, why do you hate your job? I don't know. I just hate my job. Or I'm never happy in my relationships, or I hate the house I live in. Why? If they can't answer why, that typically means they don't understand how to do an analysis.

So if you look at this model, analysis has a few basic steps. The most critical of them is to figure out an ideal state. Doesn't matter what you're thinking about, whether it's a house you want to buy, a car you want to buy, your perfect spouse, your perfect vacation, your perfect job, the idea of analysis starts with this concept that there is some ideal. There's some ideal in life, and we're not there. We're not there, and we want to be.

And then we do a comparison. So I have some ideal, and it typically has several components. And then I need to compare, point for point, how the actual situation matches up with the ideal.

As soon as we get to this point, human nature kicks in. You have an ideal. You have an actual. And it's human nature to say, well, you know what? I'm not there. I want to make some changes. I have to close a gap.

So sometimes the gaps, we dollarize, because business people, we like to have everything in dollars and cents. Sometimes the gaps are a lot more nebulous. But what we do is we, as best as we can, describe this gap between the actual and the ideal, and then we figure out how to fix it. When we've done that, we've done an analysis. OK.

Couple things. When we talk about the ideal, what's really your ideal? If you're going to buy your dream house-- Larry, if you're going to buy your dream house, what's it going to look like, your ideal?

STUDENT: My ideal is going to be a log cabin, lots of window space, facing a lake.

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK. OK. Probably you don't have any constraints about finances or anything. If you're talking your ideal, you're in the forest.

STUDENT: You said ideal. Right.

MICHELLE HOUGH: The log cabin is in it, right?

STUDENT: Right.

MICHELLE HOUGH: Right. What if I asked you-- Larry, you're being transferred to Pittsburgh.

STUDENT: OK.

MICHELLE HOUGH: It's not the kiss of death, really. You're being transferred to--

STUDENT: I'm from Pittsburgh, so no problem.

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK, good. You need to relocate to Pittsburgh next month. What's your ideal? You have to get a new house. What's the ideal?

STUDENT: Now it's going to be something closer to work.

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK.

STUDENT: If I know where I am. I still want to be in a comfortable place where I have, maybe, a little bit of property, a little bit of grounds to be outside and do my things, but probably not the log cabin home.

MICHELLE HOUGH: Right. Exactly. So what happens is ideals are constrained. We have our ideal. My ideal house, I'm telling you, it's a mansion on a cliff overlooking the ocean. That's all there is to it.

And we're not even going to talk about budget for it. Because if it's an ideal, I don't have to think about the budget, right? If I, too, was going to go buy a new house next month, it would be far, far different than that.

So what we do is, typically, we put an ideal. We put a title, buying a house, maybe. And then we put a time period, so in this case, one month. And from there we move on and we list the ideal.

OK, so let's take Larry's. OK, so if you're going to move to Pittsburgh next month, how many bedrooms you need?

STUDENT: I'll need four.

MICHELLE HOUGH: Four bedrooms. How many baths?

STUDENT: Three.

MICHELLE HOUGH: What else?

STUDENT: The actual house, location-wise?

MICHELLE HOUGH: Sure.

STUDENT: Is that OK? It needs to be accessible to community, shopping, food, entertainment, that kind of things. It needs to be close to work, reasonably close to work. But it also needs to be somewhat private.

MICHELLE HOUGH: And let's just say, because typically, we are constrained by cost, let's say Pittsburgh, $200,000, right? You can get a pretty decent house for $200,000 in Pittsburgh. So we'll call that your budget.

Then Larry's going to go out and he's going to look for houses, OK? And each house that he has, that he looks at, he's going to bump up against his ideal. We do this constantly in our lives, but we do it not consciously or not thoughtfully.

And if you're like me, I bet people you know people, or possibly you've done this yourself, you go looking for a four-bedroom, three-bath house, close to shopping, close to work, private. And you end up with a two-bedroom, one-bath with a postage-stamp yard, but it has a stone fireplace. And I always wanted a stone fireplace. And so we get distracted.

So it's important when we're doing an analysis to very clearly list what our ideals are. It doesn't mean we can't change them later for the stone fireplace or whatever it happens to be. But we have to start.

Let's say Larry goes looking for houses, and he finds a house that's three bedroom, three bath, close to shopping. It's a 40-minute commute. It's private. And it costs $250,000. You going to buy this house, Larry?

STUDENT: I'm going to consider this house.

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK, why? Let's talk about the gaps. What's the gap here?

STUDENT: My kids are getting older. I might not need four bedrooms. I might be able to accommodate three bedrooms, if it's the right house.

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK. So what happened is, right now, the gap is one bedroom, right?

STUDENT: Mm-hm.

MICHELLE HOUGH: We'll figure out how to fix it in a minute.

STUDENT: Hm. OK.

MICHELLE HOUGH: You want three baths? You got three baths. Is there a gap?

STUDENT: Happy there.

MICHELLE HOUGH: No gap. Close to shopping? Heck, yeah.

STUDENT: OK.

MICHELLE HOUGH: Close to work? What's the gap?

STUDENT: I'd say, probably, 30 minutes.

MICHELLE HOUGH: 30 minutes. Private? No gap. Cost?

STUDENT: $50,000 gap.

MICHELLE HOUGH: OK. Let's say we look at another house. And I won't write this all down. And it's a two-bedroom, two-bath, close to shopping, right next door to work. But it's a condo, and it's $150,000.

We again would go through the analysis and say, OK, we're off two bedrooms now, one bathroom, close to shopping, close to work, no privacy at all. And it's 150,000, so it's $50,000 the other way. It's a condo. How likely are you to buy that house?

STUDENT: If I don't have to take my kids, it goes way up in-- [LAUGHS]

MICHELLE HOUGH: And so, as we do an analysis with each of our possible scenarios, we have to decide on the value of the gaps, how important things are. If Larry valued privacy above all, he is not going to live in a condo, right? You're just not going to want to live in a condo. You want your yard. You want that private setting.

So we go through and we figure out how to close these gaps. And Larry was doing it automatically. This house, hey, well, you know what? Maybe I can make do on three bedrooms.

Or, well, you know what? It's three bedrooms, but there's a huge lot. I'm going to add on an extra bedroom, right? The gap with the budget, we almost always put a budget out in our mind, and then, especially when it comes to a house, exceed that budget. So that ends up being sort of a flexible one.

In the end, whenever we do an analysis, there are three possible ways to reconcile the gaps or to reconcile the situation. The first is to move the actual closer to the ideal. Build on a bedroom or decide we don't need a bedroom.

The second one is to say, you know what? This just isn't going to work. This isn't going to work. If it's a two-bedroom condo, and you want something with a private yard, it's not going to work. We're going to discard it, and we're going to look for something that's closer to our ideal state.

The other thing that sometimes happens is that, over time, we learn, and we realize that our ideal maybe isn't as ideal as we thought it should be. Over time, our priorities change.

For example, let's say-- we'll pick on the guys-- you have a picture of the perfect woman. And she's tiny and dark-haired with blue eyes. And she's a gymnast. You've always admired tiny, dark-haired women.

And one day, you meet this tall, blonde woman who isn't very athletic, and you become friends with her. And over time, you start dating her. And over time, you fall in love. I'll bet you, at some point, you're going to look at that tall, blonde woman and say, this is the perfect woman. That small, dark-haired, petite gymnast-type isn't even attractive to me any more.

So three resolutions typically. You can work your actual to move it closer to the ideal. You can abandon your actual state and say, I've got to find something different. This is what we need to do when we're miserable in our jobs.

Or for example, in Pittsburgh where I'm from, there's a tremendous percentage of people who buy a starter home and live in it for the next 50 years. And in reality, they need to move out and buy a bigger house, but they don't. The third thing we can do is decide that our actual state really is closer to the ideal than we imagine and simply decide to be happy.

Now, this has a lot of implications in business, not just in business, in life. If you're buying a house, if you're looking for a new job, if you have a project and you're bidding out a construction job. And you're trying to decide which of these three construction companies are going to give you the best deal. Well, you need to do an analysis. If you're an architect designing house for a client, you better have done an analysis, so you build the house of your client's dreams, right?

This can be applied to just about anything. I have friends who are miserable in their life. And I say, why are you so unhappy? I hate my job.

Well, what's your ideal job? And I shouldn't, I'm teaching to them. But I'm like, what's your ideal job? And we'll jot it down on a napkin. I want a close commute. And I want to be making this much money. And I want to be engaged at work.

And once you start down this path, it becomes very obvious. I hate my job because it's not engaging, and I don't make enough money, and I have a long commute. And then you start looking for another one. But the most important step is to depict the ideal. If you don't depict the ideal, you never know how close to it you can get, right?

Some interesting things I've done. I usually have my students do an analysis as a fun, little project. And then I have them, in strategy, come up and discuss their analyses. And I've have them do vacations, cars, jobs, spouses, everything in the world.

The most memorable one, though, ever, was a student who-- he was graduating. And he came up, and he did his ideal vacation. He was going to go on vacation. And it's his graduation trip. And I said, OK, Joe, give me your ideal.

And he said, you know, I want to go someplace tropical. I want to be beachfront. I want an all-inclusive vacation with a little drink with an umbrella in my hand at any given minute. I want my girlfriend there.

And he went on and on. And he had some money set aside. He was going to pay a decent amount.

And I said, OK, Joe, that sounds fantastic. Do you have a vacation planned? And he said, yes, I do. And I said, tell me about it.

He says, well, we're going to Virginia Beach. And I said, OK, how'd that come about? Well, my girlfriend's aunt has a condo there. And it's a mile from the beach. But we can rent it. And she lives next door. And my girlfriend's family's going to come with us.

And he was still going to be paying a considerable amount of money. And it wasn't all-inclusive. They were going to have to cook their own meals.

And they were going in May. Virginia Beach in May is not, by any stretch of the imagination, tropical. So I said, Joe-- we map it out. Here's the ideal. Here's the actual. Here's the gaps.

And I said, what are you going to do about this situation? I said, are you going to decide that Virginia Beach is your ideal vacation? Are you going to talk to your girlfriend and say, you know what, we need to go someplace else. Or are you going to maybe see if you can get something beachfront and start trying to move your actual closer to the ideal? And he looked at me, and swear to god, he said, dude, I'm getting a new girlfriend.

[LAUGHTER]

MICHELLE HOUGH: So analysis really, really can be a life-changing skill. Once you know how to do an analysis, whatever you happen to need to look at, you can apply a structure like this or very similar. And it'll help you to guide your thinking, so that you can perform an analysis. And people who can do analyses, in general, are happier and more successful, because they have the skills. Do you have any questions about how to perform an analysis?

STUDENT: Are there any applications where this gap analysis doesn't work so well? Are there any situations-- you mentioned houses, jobs, things. Is there any part of our lives where maybe it doesn't work?

MICHELLE HOUGH: You know, it's surprisingly robust. If you think about it, if somebody who is seeing a therapist, they go to a therapist for psychoanalysis. They're not happy with their life. And the analyst will make them [INAUDIBLE].

When it gets a little bit difficult is, for example, if you have a lot of different alternatives. And then it gets complicated because you're trying to weight the alternatives, which ones are more important out of these, first of all, which ones are more important, and which ones are less important to you.

And then, if you're presented with 20 different courses of action, trying to weigh up this course against the ideal, or this course against the ideal, or a combination, that's when it starts to get difficult, and where sometimes people just say, I'm going to go with my gut instinct. And American business managers, in particular, we go with our gut instinct.

I was in industry before I started teaching. And I have known people who have made multimillion dollar deals without doing an analysis, without really sitting down and thinking about, OK, what's the ideal? What's the best situation we can come up of this with? And in some cases, that's disastrous.

For example, think about Enron. The Enron situation, you had CEOs who, their ideal, supposedly, was to make money, profitability, profitability, profitability. But from a business standpoint, what about ethics? What about accountability? What about caring for your shareholders?

And all those things somehow got swept to the side. They assumed that they were so good at what they did that they didn't have to do an analysis of the situation. And they got into some stuff that they simply should not have done, with dire consequences for millions of people. Any other questions?

STUDENT: I actually have one.

MICHELLE HOUGH: Sure.

STUDENT: Is there someplace where you consider external constraints or the market? When we talk about getting a job, and we keep hearing it's very difficult right now because it's a tight job market. Or if Larry moves to Pittsburgh, and suppose there's just aren't many houses for sale. Is there someplace where you kind of consider external factors, how that affects your ideal and what ends up being your actual?

MICHELLE HOUGH: Right. My advice is you still have your ideal. And you may have to ground your ideal in practicality. For example, if Larry moves to Pittsburgh, and his budget is $200,000, and he can't find a house anywhere for $200,000. He's looking at $500,000 or $600,000. Then there are external constraints.

And sometimes even the choice you settle on is very far from your ideal. Just like anybody new from college getting a new job. Oh, my gosh, they want a month of vacation. They want to be making $150,000. And they want to not have to come into work. They might sometimes have some really lofty ideas.

We're all constrained by practicality. And so, sometimes, we settle for something that still is really, really far from our ideal. But we keep that ideal in mind. And we constantly look for how to move closer to it.

So if a student, a new graduate, is presented with two job offers, and both of them are below his target, let's say, of $50,000 salary. One has considerable opportunities for advancement. But the other one allows that person to travel to new and cool places. Neither one's the ideal.

And then it comes into the idea of, in your actual, how do you weight things? And how do you decide, if I can't have my ideal, what are the things that I absolutely can't compromise, and what are the things that there's some give in? And unfortunately, there are people in the world who, they have an ideal, and they won't compromise from it. And then they really are doomed to be miserable their whole life.

I have another friend, a good friend, by the way, who's my age. And when we were in high school, she went through an ideal. And I didn't know anything about analysis at the time. And she didn't either.

But she had her ideal guy. And she wrote it on a piece of paper. And she kept it. And she kept it for years, for years and years and years.

And it was hysterical, because she would go out with somebody for a couple of months. She'd give them a couple months. And then she'd pull out that sheet of paper, and she'd look it over. And man after man after man went out the door. She really got a reputation as a heart breaker.

She finally got married when she was 38 years old. And we all had given up on her by that point. She's never going to reach her ideal. And the guy she married, he met everything in her ideal. There was one minor thing that wasn't quite right, but she decided she was close enough.

And they've been married almost 10 years now. And we still were just-- it's wonderful to see, but it's sort of sickeningly sweet. They walk to the mailbox every morning holding hands, still, after 10 years of marriage. They're so happy together.

And so for years, we were just like, OK, this ideal guy, you need to be a little bit more practical. She wouldn't give up. And she finally-- she got her man. And she's very happy.

Anything else? OK. I think that's it for an analysis structure.

- Read the How to Perform an Analysis instructions below. You may want to refer to them as you watch the video.

- Click on the play button on the graphic to view the "How to Perform an Analysis" video segment.

- After watching the video, download the Strategic Analysis Form and perform your own analysis on one of the following topics: housing, a job, or a vehicle. Fill in the table and complete all steps (1-5). Save the document and submit your completed analysis to the Lesson 1: Performing an Analysis drop box. This activity is worth 20 points.

Recommended: If you are still unsure of how to proceed with a strategic analysis, please view the sample case below.

Meet Your Team

Your instructor has assigned you to teams for your collaborative course work. Each team has two private online spaces to use to discuss and complete team assignments: a Team Discussion Form and a Blackboard Collaborate room. For this module, please initiate contact with your team members using both of the tools in order to familiarize yourself with your peers and the collaborative options available to you.

Please click on each of the tools below to learn more about it and to view initial meeting assignment details.

Team Discussion Forum

One of the private team spaces available for your team is a discussion forum that only you, your team members, and the instructor can access. The discussion forum should be used for written communication and sharing files.

- Meet and Greet - Introduce yourself to the other members of your team.

- Start discussing available dates and times to meet regarding your first team project, found in Lesson 03.

Note: Any time you want to access your team discussion forum, click on the Activities link in the left-hand menu.

Team Blackboard Collaborate Room

The other team space is a virtual room in Collaborate, which is a tool that allows you to communicate synchronously (real-time) with your instructor and classmates. The software package allows users to record sessions that use real-time voice, document, and whiteboard sharing, among other features.

Before you can use Collaborate with your team, you must ensure that your computer has the necessary software installed. Visit the link below to complete the four steps for a "First Time User." Be sure to download and install the most recent version Sun Microsystems Java Web Start client, found in Step 1, because Collaborate runs on this client. You should also complete the "Online Orientation" in Step 3 to learn how Collaborate rooms work. Additionally, be sure to check the audio quality of your microphone. This process will take approximately 5 to 10 minutes. Click Here to visit the "First Time User" information. You can also access additional resources by clicking on the Collaborate link in the left-hand menu.

- NOTE: A Blackboard Collaborate room is not automatically created for your team, it must be requested. The same room can be used for the entire semester. To request a room for your team, select one team member to fill out the Collaborate Request Form survey that is located under the Activities link in the left-hand menu.

When the form is submitted, the information will be automatically sent to the Outreach Help Desk, who will create the room for you and send the requestor an email with the links you'll need to access your room. The requestor will be designated as a moderator. Moderators have access to all tools and functionality. Be sure to save the email because you'll need to send the participant links to your classmates later in the course.

If everyone on the team would like to have moderator access, be sure to include each member's full name and email address (this is highly encouraged). Anyone who is designated as a moderator will receive an email with the links. If only one person on the team is a moderator, he or she will need to send the participant links to the rest of the team members.

Learn more about moderator and participant capabilities by reading the Moderator and Participant Training Documentation

Contact your team members and select a time to meet through Collaborate.

If you have any problems scheduling the meeting, downloading the software, or participating in the meeting, please contact the World Campus Help Desk immediately.

Feel free to contact your instructor with any questions, comments, concerns regarding your team.

Introduction to the Individual Writing Assignment

This lesson you need to begin thinking ahead about your individual writing project which has multiple deadlines throughout the semester (see the syllabus). In this assignment, you'll be analyzing a real company so pick one with which you are familiar from the provided list. There is no graded deliverable this lesson for this assignment—your main task is to select a company to write about in the upcoming individual paper. This is a great opportunity for you to research an industry or company that you might be interested in working for. Company selection is on a first-come, first-served basis. Post your selected firm to the Lesson 1 Company Selection Forum. If a classmate in the forum has already selected the company you wanted, choose another from the provided list.

Review the syllabus to see what's expected in the paper and review the grading rubric to see how the paper will be graded. The first assignment is to develop a reference list of at least 20 credible, published sources. Use the vast and free resources of the Penn State library. Please refer to the business research guide that the library has developed.

I would recommend using Hoover’s for company overviews and financials, and ABI Inform to find current articles. You can also use the company’s annual report and its proxy statement (SEC document DEF 14A). Using ABI, it is important to narrow your search by adding company and another keyword.

Because this project is worth 400 points, or 40% of your final grade, make sure you start writing early. You also have enough information now to start writing the first section of Part 1, Draft 1.

- First Page

- Previous Page

- 4

- 5

- 6

- Next Page

- Last Page