Main Content

Lesson 2: Origins of Mass Media

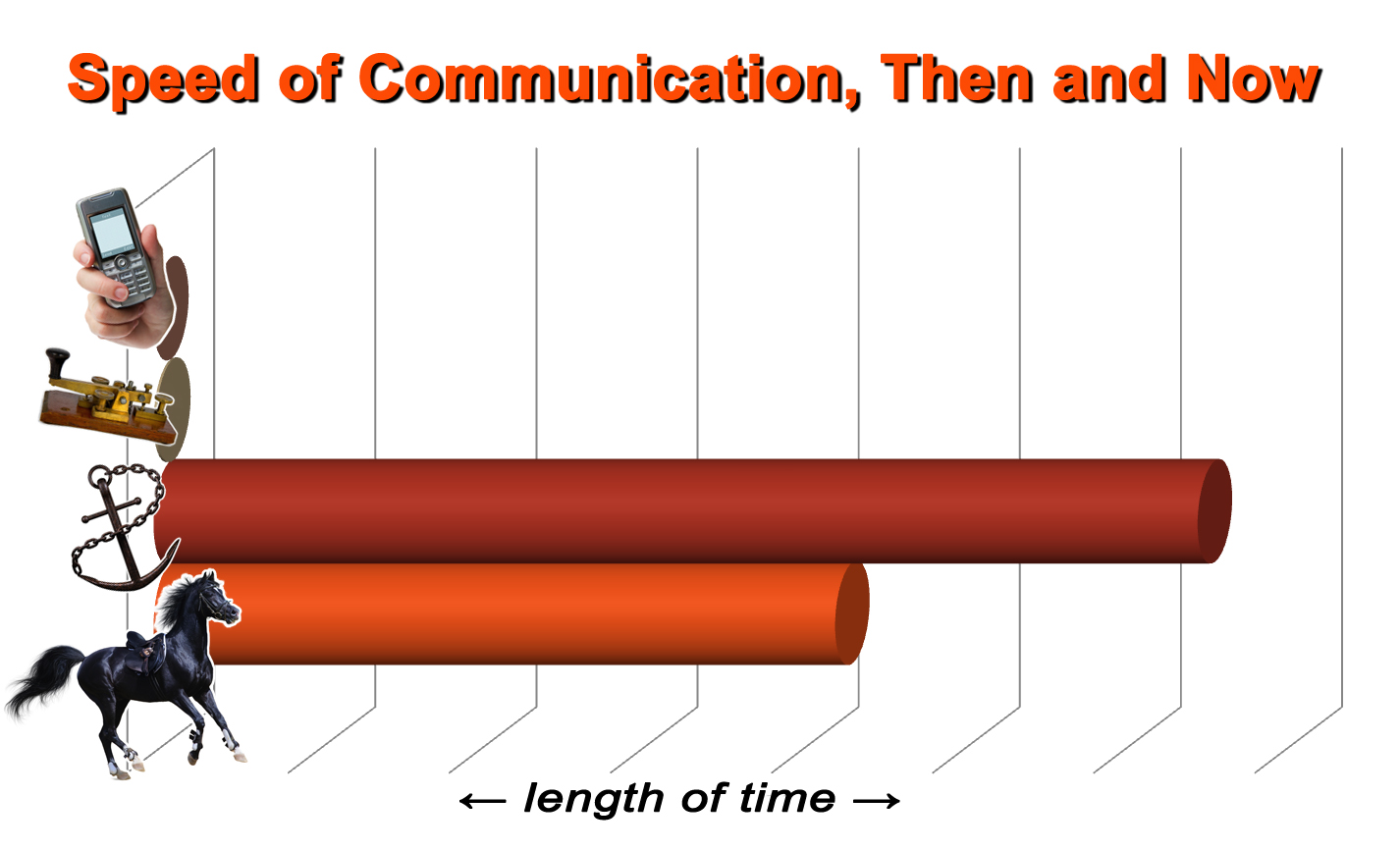

Communication Yesterday and Today

For most of human history, face-to-face was the only type of communication that took place. The invention of writing allowed information to be stored for later consumption without having to commit it to memory. This invention dramatically increased accuracy and allowed for increasingly complex thought. But for almost all of human history, the speed of communication was very slow. Simple information could be communicated over long distances by playing loud drums or using smoke and fire as signaling devices. Carrier pigeons could also be used to send short messages over long distances faster than a person could travel. But when sending long, complex messages, the speed of information was still limited to the speed at which a person could travel. The famous Pony Express took 10 days to travel 2,000 miles across the United States. Similarly, in the mid-1800s, it took ships 10–14 days to cross the Atlantic from the United States to Europe. If you sent a letter to Europe, you would have to wait a month or more before you received a reply! The telegraph was invented in the 1830s, and the first commercial telegraph line in the United States was established between Baltimore and Washington, DC, in 1844. Suddenly, information could be sent instantaneously! Today, we grow impatient when someone does not reply to our text message or email right away. The next time you get frustrated, just think of what life was like before electronic communication!

For most of human history, face-to-face was the only type of communication that took place. The invention of writing allowed information to be stored for later consumption without having to commit it to memory. This invention dramatically increased accuracy and allowed for increasingly complex thought. But for almost all of human history, the speed of communication was very slow. Simple information could be communicated over long distances by playing loud drums or using smoke and fire as signaling devices. Carrier pigeons could also be used to send short messages over long distances faster than a person could travel. But when sending long, complex messages, the speed of information was still limited to the speed at which a person could travel. The famous Pony Express took 10 days to travel 2,000 miles across the United States. Similarly, in the mid-1800s, it took ships 10–14 days to cross the Atlantic from the United States to Europe. If you sent a letter to Europe, you would have to wait a month or more before you received a reply! The telegraph was invented in the 1830s, and the first commercial telegraph line in the United States was established between Baltimore and Washington, DC, in 1844. Suddenly, information could be sent instantaneously! Today, we grow impatient when someone does not reply to our text message or email right away. The next time you get frustrated, just think of what life was like before electronic communication!

|

Mode |

Speed |

Distance |

|---|---|---|

|

Voice/drums |

1,000 feet per second |

Depends on atmospheric conditions and volume. Usually less than 30 miles. |

|

Smoke/fire |

Speed of light |

Depends on atmospheric conditions and height. Usually less than 30 miles. Can only send very simple messages. |

|

Carrier pigeon |

50 mph |

500 miles in 10–12 hours. Can only carry 3 ounces. |

|

Horse/Pony Express |

10–15 mph |

Missouri to California in about 10 days |

|

Railroad—late 1800s |

50 mph |

New York to California in 7–10 days |

|

Sailing ship—1700s |

10 mph |

North America to Europe in 6–8 weeks |

|

Steamship—late 1800s |

15–25 mph |

North America to Europe in 10–14 days |

|

Telephone/telegraph wire |

2/3 speed of light |

Anywhere on earth in less than 1 second |

|

Radio waves |

Speed of light |

Anywhere on earth in less than one second |

Video 2.4 shows an example of signal fire communication from Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.

Reflection Questions

How is this newer, faster, smaller, cheaper technology a positive thing for mass media? How does it hurt mass media? Is it always an improvement in daily life? Are there times when these technological developments may hinder society's growth?

We now live in a 24/7 media environment where major world events like wars and natural disasters are reported instantly. The 20th century saw the rise and maturation of mass media, where content producers focused on reaching the largest possible audience. As we move into the 21st century, we see content producers using newer digital technologies to create customized content for individuals. The average household today can choose from an almost unlimited number of television and film choices from multiple streaming services and cable channels compared to choosing among 4–5 broadcast stations in the 1970s. Spotify and Pandora have become major sources of music distribution, and each provides customizable stations and playlists. Meanwhile, cable news has to find content to fill up 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. Many observers feel much of this airtime is filled with speculation and uninformed opinion that harms democracy rather than helping it. The instantaneous nature of electronic media creates pressure to provide instant answers that are often wrong. Perhaps we would be better served if the media resisted that pressure and allowed for more thoughtful reflection.

The Rise of Web 2.0 and New Communication Networks

Another fundamental shift, often referred to as Web 2.0 signaled the rise of user-generated content. In the 20th century, a few large companies produced most of the content we consume. Today, YouTube videos, blogs, Facebook, and Twitter allow all of us to be content creators. Instead of only choosing among dozens of video channels or hundreds of newspapers, we can now select among an almost infinite variety of content.

The change is not just in the content we consume for entertainment and news (mass media) but also in our interpersonal communication. A hundred and fifty years ago, the only way to talk to someone was face-to-face or by sending a letter. Even as recently as 30 years ago, the only improvement was the ability to use a landline telephone—and making long distance calls was very expensive. Today, we can send instant messages and video chat with one or dozens of friends around the world simultaneously, and the cost is practically zero! This change makes it much easier for us to keep in touch with old friends and make new friends.

Another area that has changed is commerce. Record stores and video stores have all but disappeared and even bookstores are struggling to survive. Even nonmedia businesses have changed. Few people use a travel agent since we can now shop for airline flights, hotels, clothing, cars, and everything else imaginable online.

Just as important as the changes described above is the fact that we continue to increase the amount of time we spend using telecommunications. We now spend more time using media than just about anything else we do. We use it so much that it is hard to recognize how pervasive it is.

Watch Video 2.5 for a reflection on how Web 2.0 has changed communication:

[MUSIC - DEUS, "THERE'S NOTHING IMPOSSIBLE"]

(The following is a description of the actions occurring in the video.)

A close-up of a hand writing these words with a pencil: "Text is linear." "Uni" is added to the word linear. A caret mark is placed in between is and unilinear, and the words "said to be" are inserted. The word "often" is added before "said to be." The sentence now reads, "Text is often said to be unilinear." The words "often said to be" are erased and replaced with "when written on paper," so that the sentence reads, "Text is unilinear when written on paper."

In the next shot, a cursor appears and this sentence is typed on the screen: "Digital text is different." The sentence is edited multiple times. "Digital text is flexible, moveable, is above all...hyper." As these items are being typed out, they are also showing what the words are describing. For instance, "hypertext can link" is the next sentence that appears, and it shows the word link as an actual link. When the link is clicked on, it shows that links can take you anywhere.

The video transitions to a shot of the website WayBackMachine. "http://Yahoo.com" is in the search bar. When the cursor clicks on the button "Take Me Back," a list of dates appear with all the pages that existed during each year. A link from October 1996, is clicked on. The cursor right-clicks on the screen and selects "View Source" from the drop-down menu. The source code for the website appears. The following text is typed into the code: "Most early websites were written in HTML. HTML was designed to define the structure of a web document. <p> is a structural element referring to 'paragraph.' <Li> is a structural element referent to a 'list item.' As HTML expanded, more elements were added, including stylistic elements like <b> for bold and <i> for italics. Such elements defined how content would be formatted. In other words form and content became inseparable in HTML."

All the text is then highlighted in the code and deleted. The following sentences are typed: "Digital text can do better. Form and content can be separated."

An example of XML is displayed. Text is typed into the code: "XML is designed to do just that. <title> does not define the form. It defines the content. Same with <link> and <description> and virtually all other elements in this document. They describe the content, not the form. So the data can be exported, free of formatting constraints."

The video transitions into a shot of Google.com with the following typed into the search bar: "With form separated from content, users did not need to know complicated code to upload content to the Web."

The cursor clicks on the I'm Feeling Lucky button. This opens the blogger website. It shows how quick and simple it is to create a blog. A shot from News.com is shown, and this sentence is in bold: "There's a blog born every half second." The Google search bar is brought up again and the words "and it's not just text..." are typed into the text box. When search is clicked on a series of shots from YouTube, Flickr and other websites appear.

Google.com is brought up again. "XML facilitates automated data exchange" is typed into the search bar. That is erased and replaced with "two sites can 'mash' data together." Again, this is erased and replaced with "Flickr maps." Then the "I'm Feeling Lucky" button is clicked on. A shot of Flickr maps is shown. This question is brought up: "Who will organize all this data?" A series of shots that show the tagging action on various websites. The answer to the question appears: "We will. You will."

Google.com is brought up. In the search bar "XML + U & Me create a database-backed web" is typed.

An article is shown: "We are the Web." Various parts of sentences are highlighted throughout the article forming these sentences: "When we post and then tag pictures, we are teaching the Machine. Each time we forge a link, we teach it an idea. Think of the 100 billion times per day humans click on a web page. Teaching the Machine."

"The machine is using us. The machine is us."

The following text is typed onto a white screen: "Digital text is no longer just linking information... The Web is linking people, Web 2.0 is linking people...people sharing, trading, and collaborating." The video transitions to a shot of editing a Wikipedia page. All the content is removed, and the following is typed on the page: "We'll need to rethink a few things, such as copyright, authorship, identity, ethics, privacy, etc."