Main Content

Lesson 2: Critical-Cultural Theories

How Theory Will Be Used in This Class

In most cases in academia, theories are used in research to test hypotheses. This is not a research class, so instead, we will use theory as a way of understanding the media better.

If nothing else, your goal is to understand generally what each theory means, to recognize them in use in the research papers we will read, and to understand how theory is being used to make sense of the world or our perceptions of it.

For example, last week one of the papers listed on the What does "critical-cultural" mean? lesson page was called Examining the rage donation trend: Applying the Anger Activism Model to explore communication and donation behaviors. In that article, the researchers use the Anger Activism Model to make sense of a phenomenon they observed about how/when/why the public makes charitable donations based on anger. You would need to understand the Anger Activism Model in order to understand their research findings.

For that reason, we are starting with theory as a way to build a set of shared knowledge to make sense of the course readings. Look for the theories covered in this lesson as you read research papers and watch films during the rest of the semester. At your best, I would love to see you identify and unpack the theories used because researchers choose which theories to apply very carefully. They can be as laden with ideology as a documentary about immigration and can shed light on the researchers' perspectives and possible biases.

Being able to critically engage with research papers is a fundamental skill in media literacy. Journalists are often very bad at this and jump at one catchy aspect of the findings instead of digging into the whole paper to understand the context. Using media literacy combined with an understanding of why theory matters and what it means will give you an essential skill set to better engage with the media.

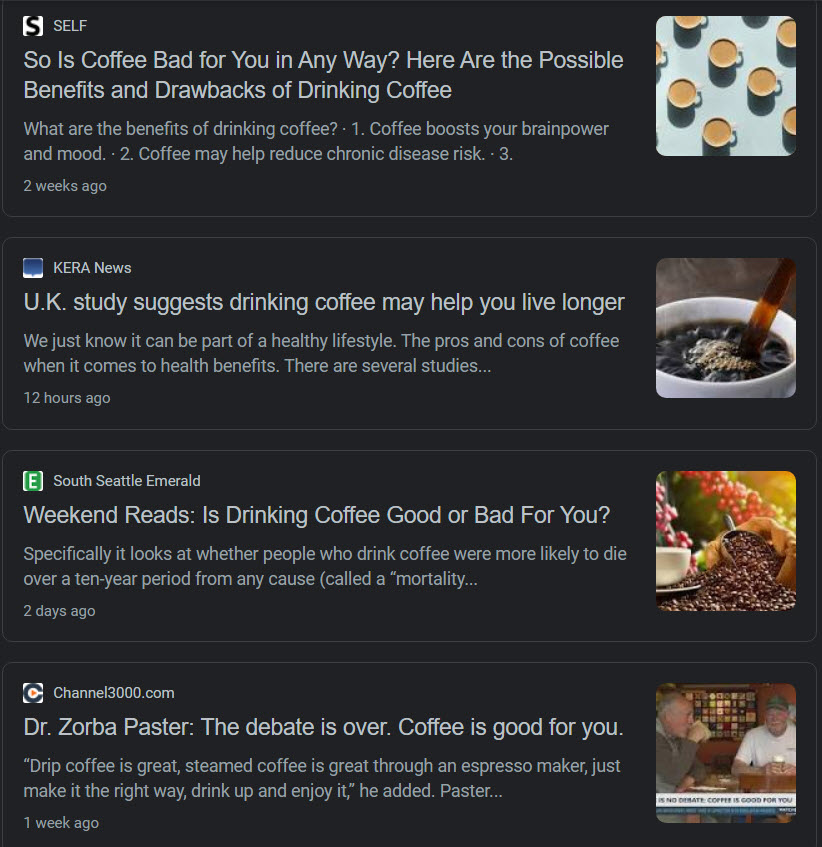

For example, a study released in mid-2010s seems to indicate that drinking coffee helps you live longer. Or does it? From the results shown in a simple Google search (Figure 2.1), no one seems sure.

Without access to the original study and the tools to make sense of the researchers' hypotheses and results, the public is only getting part of what the study found, what the journalists thought was important, and why it might matter to those of us who dearly love multiple cups of coffee each day. Filtered through all of those layers, the information being consumed by the public is limited and could be misleading.