Main Content

Lesson 2: Theory and Criminal Justice Research

Ancillary Issues Pertaining to the Traditional Model of Science

By this point you’ve probably realized that our focus in this course will be upon formulating hypotheses, and the subsequent scientific methods used to test those hypotheses. Within this framework of the Traditional Model of Science are a few ideas that need to be addressed prior to delving further into the specifics of the Model. A number of these terms you've undoubtedly heard before, but perhaps like most people, never really gave much consideration to their meaning. Below is a discussion of these ideas and, hopefully, some perspective will be given to how these ideas fit within the scientific lexicon.

There are two ways to go about producing knowledge scientifically within the Model of Science: deductively and inductively. While these terms represent different perspectives on how one starts inquiry into a topic, the differentiation is not overly important, as you’ll soon see. Deduction and induction simply refer to how one starts the inquiry process. In terms of the Model of Science, the reference is to where the process begins. Deduction is also commonly known as theory testing. In the example above of Shaw & McKay, they used deductive logic in testing their ideas about disorganization and crime.

There are two ways to go about producing knowledge scientifically within the Model of Science: deductively and inductively. While these terms represent different perspectives on how one starts inquiry into a topic, the differentiation is not overly important, as you’ll soon see. Deduction and induction simply refer to how one starts the inquiry process. In terms of the Model of Science, the reference is to where the process begins. Deduction is also commonly known as theory testing. In the example above of Shaw & McKay, they used deductive logic in testing their ideas about disorganization and crime.

As previously stated, Shaw and McKay were greatly influenced by Burgess and his concentric zones, and Burgess's model led them "to the conclusion that neighborhood organization was instrumental in preventing or permitting delinquent careers" (Lilly et al., 41). They ventured out to find if Burgess's model held up; that the highest rates of crime would be in the zone of transition, and would decrease outward. Shaw and McKay studied juvenile court statistics and confirmed the predictions by Burgess.

To deduce is to begin with a specific theory or idea, then use general observations to test that theory. Thus, deduction always begins at the "top" of the Wheel of Science with theory. Inductive logic, by contrast, begins at the "bottom" with general observations which subsequently become a specific theory or idea. Many anthropologists conduct their research in this way -- observing a culture and then drawing specific conclusions from the observations made. The work of Margaret Mead is perhaps one of the best examples of inductive reasoning. The Margaret Mead Biography offers a summary of her work.

While the distinction is procedural, it becomes a moot point after the scientific process has started simply because, for example, once a theory is developed from observation, it must then be re-tested deductively. And after an initial theory is modified on the basis of observation, it is re-tested inductively. Therefore, because the scientific testing process is continual, the system of logic chosen only indicates how enquiry was begun. Some scientists prefer to start with a 'clean slate' inductively; others prefer to start with a previously held idea or assertion. Either method is fine, as long as the scientific process is utilized correctly.

As grade-schoolers, we were introduced to certain scientific laws that have become second nature to us, like the Law of Gravity. In social science there are no laws, or absolutes, because our subject is human behavior, and human beings are not constant. This idea, in my opinion, makes our field of study that much more challenging. While the chemist knows that two hydrogen molecules and one oxygen molecule will always produce water, we can never say with 100 percent certainty that a social factor will always produce a particular outcome. Therefore, we seek to establish patterns of behavior applicable to groups, and tend to shy away from trying to predict individual behavior. And as an aside: don’t confuse scientific laws with laws as legal statute that we are familiar with in criminal justice. Statutory law is not constant, obviously, laws can and do change – they are a byproduct of human behavior.

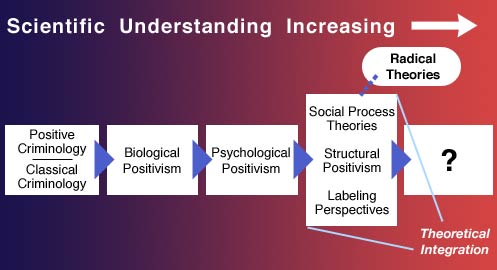

A paradigm is best defined as the conventional wisdom or general frame of thinking related to a time period. Paradigms define the scientific climate of the time within which the traditional model of science operates. For example, early criminologists focused on biological determinants of criminal behavior and the science that was undertaken by the Positivists reflected the notion that criminal behavior was thought to be based in human physiology.

As the thinking changed, a paradigm shift occurred that led criminology to focus on psychological explanations of crime, and then social factors. Presently we are operating in the paradigm which views criminal behavior as a product of the social milieu, but we are braced for another shift in paradigm. The next paradigm will undoubtedly incorporate what we’ve learned from the field of genetics to aid in explaining the social context of deviant behavior. As you can see, the scientific enterprise drives the overall perspective or paradigm; the paradigm shifts when science becomes more advanced and challenges the prevailing wisdom.

Figure 2.1: Paradigm Shift in Theorietical Criminolog